Yosa Buson: A Master of Haiku and Painting

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Unbound by Teachers and Schools

The haiku poet and artist Yosa Buson was born in the village of Kema near Osaka in 1716. His actual surname is thought to have been Tani or Taniguchi, but he later used the name Yosa. One theory has it that his mother came from Yosa in Tango province (now Kyoto Prefecture), but nothing is known of her family or family business. His father was the village head of Kema.

Around the age of 20, he went to Edo (now Tokyo), where he became a follower of Hayano Hajin, living with him in Nihonbashi and studying haikai, a form of playful literature in prose or poetry (such as haiku); at this time, he took the literary name of Saichō. Hajin was a poet with a free and natural style who had, in turn, learned from two of Matsuo Bashō’s disciples: Kikaku and Ransetsu. Buson later recalled how he had realized the unfettered nature of the form, when Hajin taught him that haikai students should not be bound by their teachers’ methods. This influenced his thinking that haikai should also not be restricted by the rules of different schools.

After Hajin died in 1742, Buson was helped by an older follower called Gantō to move to Yūki in what is now Ibaraki Prefecture. He spent some time drifting around northern Kantō, honing his skills in painting and haikai, and traveled as far as Tōhoku. With Gantō’s encouragement, he produced a collection called Utsunomiya saitanchō (Utsunomiya New Year Poems), which is when he first adopted the name Buson. This name is thought to mean “overgrown village,” taken from a poem by the Chinese writer Tao Yuanming.

He wrote “Hokuju rōsen o itamu” (Mourning for Hokuju) for a friend and senior member of the Yūki haikai circle who died in 1745. This was a haishi, which is a long form with elements of both haikai and kanshi (Chinese poetry), pioneered by Bashō’s disciples and refined among Edo poets. Buson displayed his high level of poetic skill in the work. The opening is as follows.

You left this morning. This evening, my heart is in a thousand pieces. / Why did you go so far away? / I think of you walking in the hills. / Why are the hills so sad?

Painting Prowess

In 1751, Buson moved to Kyoto when he was in his mid-thirties. As there is no record of him having had a specialist painting teacher, he is believed to have taught himself artistic technique by walking around to study artworks at Kyoto temples and shrines. He also sought out paintings further afield in the provinces of Tango and even Sanuki in Shikoku (now Kagawa Prefecture).

In the eighteenth-century Japanese art world, a new style called Nanga, which was influenced by China’s Southern School, became popular due to the stay of Chinese painter Shen Quan in Japan and the publication of manuals on painting theory and method. Buson eagerly studied these books and gradually made a name for himself as a Nanga artist. In 1771, he collaborated with Ike no Taiga, a lifelong rival, on a work called Jūben jūgi zu (Ten Advantages and Ten Pleasures). This was based on a poem by Chinese writer Li Yu comparing the comforts of his vacation home with the wonders of nature; Taiga painted the “ten advantages,” while Buson depicted the “ten pleasures.” In the field of painting, this is Buson’s masterpiece.

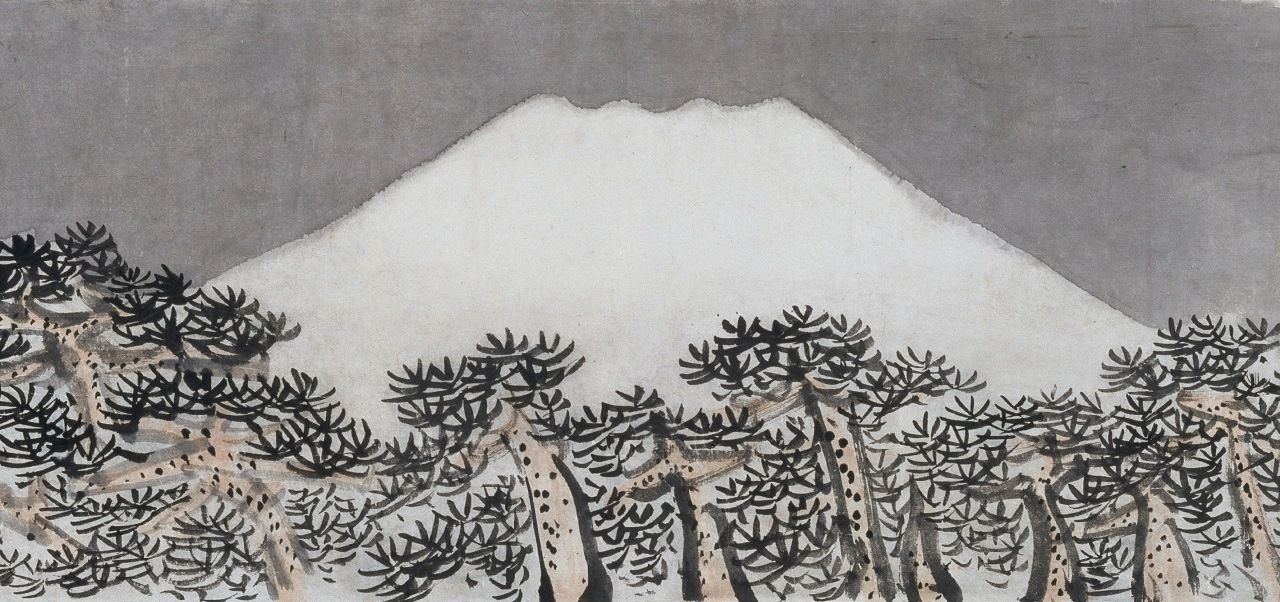

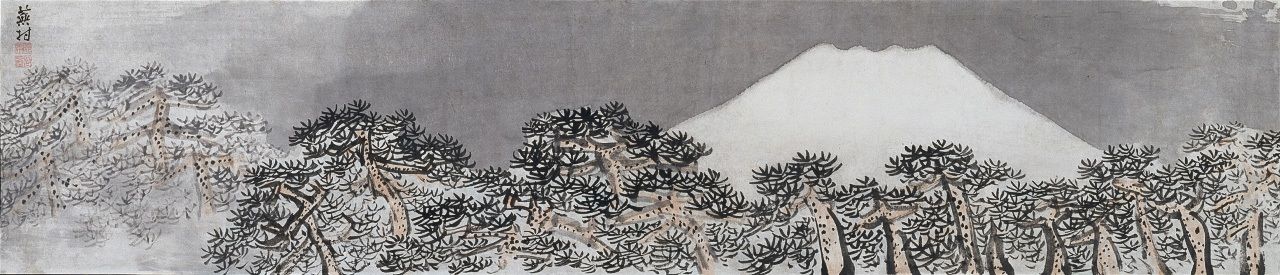

From this time, he was in his artistic prime as a painter, completing such works as Fugaku resshō zu (Mount Fuji Beyond Pine Trees).

Detail from Fugaku resshō zu (Mount Fuji Beyond Pine Trees). (Courtesy of the Kimura Teizō Collection at Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art)

Fugaku resshō zu (Mount Fuji Beyond Pine Trees). (Courtesy of the Kimura Teizō Collection at Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art)

Words and Pictures

He was also active in Kyoto as a haikai poet, forming a haikai association in 1766 and holding regular gatherings to compose poems on set themes. These were lively affairs in which the participants freely discussed the merits of the poems, and while they came to a temporary halt at the time Buson traveled to Sanuki, they resumed on his return to Kyoto. The gatherings allowed Buson to polish his technique and produce such masterful works as the following.

鳥羽殿へ五六騎いそぐ野分哉 蕪村

Toba dono e / gorokki isogu / nowaki kana

Five or six horsemen

race to Toba Villa—

autumn tempest

In 1770, Buson took the literary name of Yahantei, which had formerly been used by Hajin, and became a formal haikai master in Kyoto. As he was in his mid-fifties, this was a very late start. He seems to have prioritized his artistic work over literary pursuits.

Buson’s art and writing were deeply connected. In the form known as haiga, a combination of haiku with rough sketches, Buson was in his element, producing many marvelous works where the poetic sentiment and humor of words and illustration chimed together. There was particular demand for his rendering of the full text of Bashō’s Oku no hosomichi (trans. by Steven D. Carter as The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands). His light brushwork and sketches of people drew fulsome praise, and appear in numerous works, such as picture scrolls and folding screens.

Buson’s view of haikai was greatly influenced by painting theory. In his Rizokuron (A Theory of Leaving Behind the Vulgar), he stated that one should write haiku after removing all vulgar spirit from one’s heart. He also said that while there are many haikai schools, writers should make them all their own, choosing to write haikai in a style according to their taste to fit with the time and place.

This is adapted from the Chinese book of painting theory Jieziyuan huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden). In Buson’s day, the popular thinking among the literati was that one should study the Chinese and Japanese classics, as well as painting, calligraphy, music, and other various arts, to escape vulgarity. Buson believed that haikai was created when in a spiritually rich state of mind.

Literary Wit

After he became a haikai master, the Buson school produced a series of major anthologies: Sono yukikage (Gleam of the Snow, 1772), Akegarasu (Dawn Crow, 1773), and Zoku akegarasu (Sequel to Dawn Crow, 1776). Amid the jumble of various competing schools in the late eighteenth century, there was a strong desire to create a new post-Bashō era of haiku. Buson’s followers were no exception. However, Buson’s disciple Kitō edited these anthologies, while Buson himself is thought to have just provided guidance.

Many of the collections Buson edited were small pamphlets with haiku from close friends and disciples. They showed a variety of styles, chosen according to his tastes. In An’ei kōgo saitan (An’ei Kōgo [1774] New Year Poems) Buson illustrated the haiku of his followers, but not necessarily in a way that straightforwardly matched with their meaning.

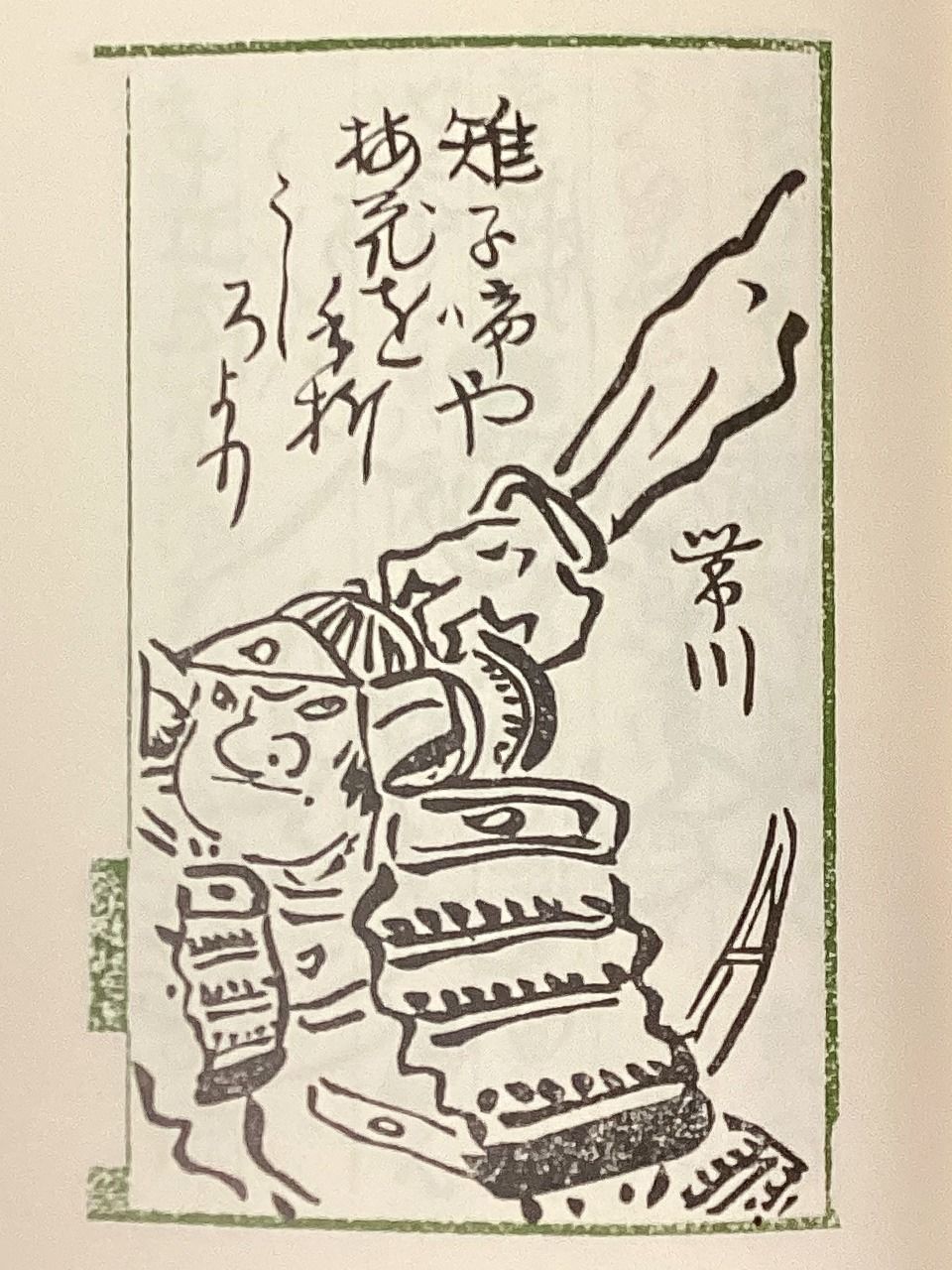

雉子啼や梅花を手折うしろより

Kiji naku ya / baika o taoru / ushiro yori

Pheasant’s cry—

as I broke off a plum blossom,

the call came from behind

For this haiku composed by his disciple Taisen on a walk in early spring, Buson sketched the famous scene from the Rashōmon nō drama in which the oni or demon of the Rashōmon gate in Kyoto attacks the warrior Watanabe no Tsuna from the rear, seizing his helmet. At first, this seems to have nothing to do with the haiku, but it shares the aspect of a surprise from behind. It displays Buson’s enjoyment of intellectual play, based on his knowledge of the classics.

Buson’s illustration for his disciple Taisen’s haiku. (Courtesy Waseda University Library)

In “Shunpū batei kyoku” (Spring Breeze on the Kema Embankment) from the 1777 collection Yahanraku (Midnight Music), he expresses his own keen nostalgia through the medium of a servant girl traveling home from her place of service. The sequence consists of 18 sections, mixing haiku, Chinese poetry, and Sino-Japanese prose. Below are two poems from the middle of the sequence, and the final section, prefaced by a line from Buson asking whether the reader might have seen the closing verse before.

A dandelion plucked

gently—white liquid brims from

its short stalk

A long time ago . . .

I recall my mother’s tenderness—

within her robe,

a special warmth unlike

the world’s spring

Do you know this haiku by the late poet Taigi?

A servant home for a few days’ holiday,

the girl sleeps beside

her solitary mother

The milk-like liquid from the roadside dandelion in the first poem leads on to thoughts of the girl’s mother. In the third poem, we see Buson’s novel approach of using another poet’s haiku to round off the whole sequence. Overall, the array of literary forms depict the passing scenery and emotions of the girl as she dwells on her mother. Buson shared these kinds of experiments only with his circle of intimates. Perhaps this was because haikai was a pastime for Buson in which he could let his spirit play freely. For a man like him, who was busy as a painter, it also provided emotional relief.

Buson died in 1784, at the age of 68. Below is his final poem.

しら梅に明(あく)る夜ばかりとなりにけり

Shiraume ni / akuru yo bakari to / nari ni keri

Amid white

plum blossoms, dawn

breaking now

While Buson respected Bashō, he combined poetic sentiment and wit in his haiku in an approach that was quite different from the plain style favored by those of his time who considered themselves to be in the Bashō school. He restored a hut known as Bashō-an, once used by his predecessor, at the Kyoto temple of Konpukuji. Buson’s grave can also be found at the temple.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 31, 2024. Banner image: Portrait of Yosa Buson. Courtesy of the National Diet Library.)

Related Tags

literature Yosa Buson haiku Japanese language and literature