Express Train to Industrialization: Japan’s First Railway Line

History Politics Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Model Trains

In July 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with the US Navy East India Squadron off the coast of Edo (now Tokyo), and demanded that Japan open up to foreign trade. When he returned in March the following year, the shogunate bowed to American pressure and signed the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity

While the great warships belching steam and firing blank rounds threw fear into the hearts of the Japanese, on his second visit Perry also made a gift to the shogunate of a quarter-size steam locomotive.

Perry brought a railway engineer with him to Yokohama, where he had a circular track of around 100 meters laid beside the sea, and ordered the locomotive to be loaded with coal and set to run. It traveled at around 32 kilometers per hour. Shogunate official Kawada Hachinosuke was thrilled when he took an experimental ride on the miniature vehicle, declaring it “very enjoyable” and praising the locomotive’s speed. Perry also gave presents of US weapons and telegraph equipment to impress on the shogunate the advanced nature of Western civilization.

US Commodore Matthew Perry. (© AFP/Jiji)

The following year, Saga domain (now Saga Prefecture) created a model steam train through its own efforts and gave it a successful test run.

Shortly after Perry first arrived in Japan, Russian naval officer Evfimii Putiatin travelled to Nagasaki in August 1853 and made his own calls to the shogunate to open up the country. He allowed visitors to board the Russian ships, where there was a model of a steam locomotive on display. The Saga leader Nabeshima Naomasa had previously established a scientific research center called Seirenkata, tapping talented engineers to research and manufacture Western devices like reverberatory furnaces and cannons. Seirenkata scholars studied Putiatin’s model locomotive, and used related books in making their own version.

Despite its isolation, Japan had not been left behind and its people of the time were skilled at imitating Western machinery.

Tanaka Hisashige was at the center of the manufacturing process. He was renowned as a creator of mechanical dolls called karakuri ningyō, and had also produced various inventions in Osaka and Kyoto, such as a self-refueling oil lamp that burned longer than other lamps, and a complex spring-driven chronometer. Naomasa highly valued Tanaka’s talents, making him a domain retainer, and setting him to research and develop steam engines as a key Seirenkata member. Tanaka went on to found the forerunner of Toshiba.

A karakuri ningyō created by Tanaka Hisashige. Able to write characters, the doll dips its brush in ink and can reproduce various kanji in a lifelike manner. (© Jiji)

British Influences

Japan did not create a full-fledged rail network, however, until the Meiji era (1868–1912). While France and others recommended that the shogunate start building railways, government leaders were indifferent to the advice, and it was not until January 1868 that the senior shogunate official Ogasawara Nagamichi approved a plan by US diplomat Anton L. C. Portman to construct a line between Edo and Yokohama. Under this scheme, the United States would essentially take on both the work of laying the track and management rights.

Just a few months later, however, the shogunate unconditionally surrendered in Edo to the forces that would establish a new Meiji government, which tore up the agreement with Portman. At the urging of Harry Parkes, the British consul general to Japan, the Meiji government decided that while it would turn to the British for help, it would run the railway independently.

Ōkuma Shigenobu, a vice minister in both the Ministry of Popular Affairs and the Minister of Finance, took over the task of building Japan’s first railway. Being from Saga, he had presumably seen the locomotive manufactured by Seirenkata and hailed from an area with respect for Western knowledge. To modernize Japan and bring it alongside the Western powers, it would be necessary to build the country’s economic strength as quickly as possible. He believed there was a pressing need to establish a transportation network as one way of achieving this goal, and was able to put his rail plans into effect, overcoming opposition from others who wished to prioritize the development of warships

British railway engineer Edmund Morel oversaw line construction, while the costs were largely covered by loans from Britain, and the steam locomotives were British-made. Track gauges were in line with British standards, although these were the narrower kind used in Britain’s colonies. Thus, Japanese railways were much narrower than those in the West, as were its trains.

Horatio Nelson Lay, a British financier that Parkes introduced to the government, was put in charge of procuring funds and materials. He was fired, however, when he was found to be angling for illicit profits. By the time of his dismissal though, orders for secondhand engines and narrow-gauge rails had already gone through. Ōkuma later regretted the use of the narrower rails as the blunder of a lifetime.

Rails Across the Water

In April 2019, traces of the nineteenth-century railway were discovered during improvement work by JR East at Shinagawa Station. The Takanawa Embankment was constructed using earth from Tokyo Bay, reinforced with stone on either side, and rails were laid on the top.

Part of Takanawa Embankment has been designated as a national historic site. (© Jiji)

Construction of the 2.7-kilometer embankment, which was 6.4 meters wide, began in 1870 in the shallow waters of Tokyo Bay. The stone walls used the traditional sloping norimen method. The beautiful stonework and arcing shape combine in a blend of Japanese and Western styles that is now a valuable example of modernization heritage.

Why was the railway built over the water? The planned route included land belonging to the Ministry of War (later to be divided into separate ministries for the army and navy), and Saigō Takamori, who was in charge of the military, and other high-ranking ministry officials were reluctant to relinquish that land. This led to the decision to construct stone walls and a line going over the water.

Saigō considered the strengthening of military power as of primary importance, to which developing transportation was secondary. He also opposed borrowing money from the British, believing it could lead on to invasion.

First Journey

Railway construction work began in 1870, but before its completion the British overseer Morel died of lung disease at the age of just 30. His assistant John Diack took over, supported by Inoue Masaru, newly appointed as Japan’s first director of railways.

Inoue was from Chōshū (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) and was one of the famous Chōshū Five, who covertly left Japan in 1863 to study in Britain. He learned about mining and rail technologies in London before returning to Japan in 1868. The following year, he started working for the Meiji government, and took on a major role in railway construction after Morel’s death.

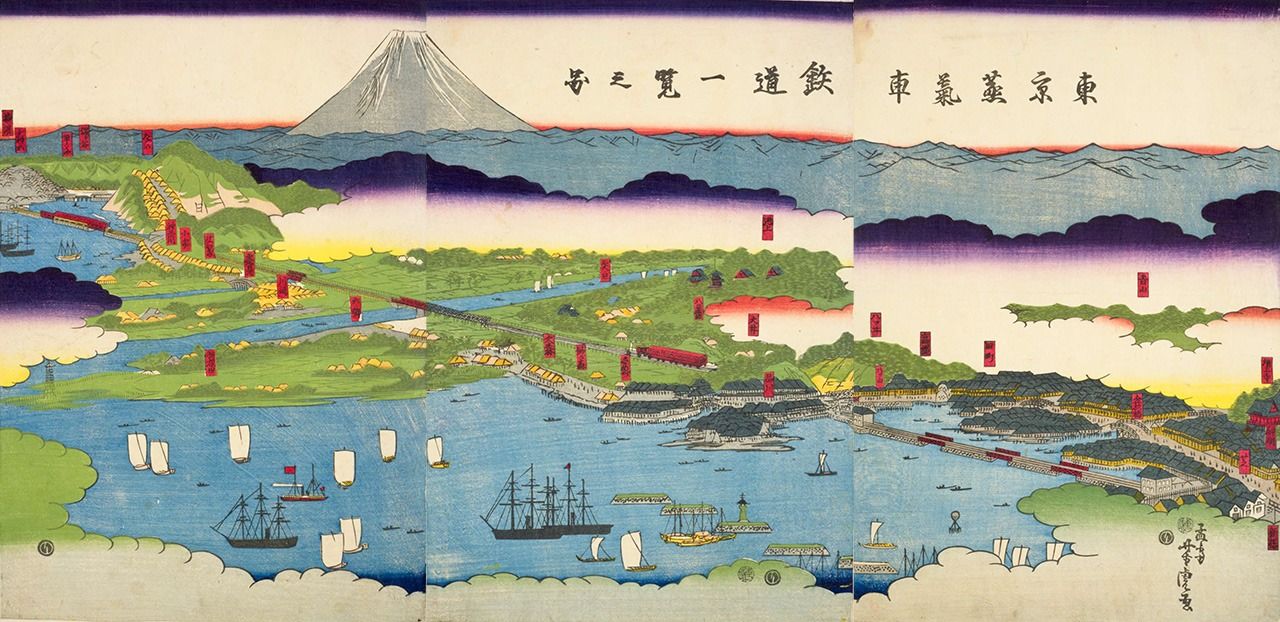

An imagined rendering of the Tokyo railway by Mōsai Yoshitora, printed the year before the line began operations, demonstrates the expectations of the Japanese public. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

After considerable efforts to complete the line, Japan’s first railway began operations on October 14, 1872. A grand opening ceremony was held at the newly constructed Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, attended by Emperor Meiji. High-ranking government officials and foreign dignitaries were present, while ordinary citizens were also allowed to observe. One fascinating element was that the government officials wore hitatare, the traditional samurai clothing, which seemed out of step with a ceremony focused on modernization.

Shinbashi Station in 1872, shortly before the start of rail operations. Designed by US architect Richard Bridgens, it became used only for freight after Tokyo Station opened in 1914, but was destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. (Courtesy Japanese National Railways Settlement Corporation; © Jiji)

The former Shinbashi Station, reconstructed in Shiodome in 2003. During excavation work ahead of redevelopment, original platforms and other remains of the railway were discovered, and some of these are on display in the building. The area has been designated as a national historic site. (© Jiji)

At the ceremony, Emperor Meiji gave an imperial address, expressing his joy at the completion of the railway and his wishes that it would expand in the future across the whole of the country. After the ceremony, he boarded the train, which traveled 23.8 kilometers from Shinbashi to Yokohama before returning. In his carriage were many important Japanese statesmen, including Sanjō Sanetomi, Yamagata Aritomo, Ōkuma Shigenobu, Etō Shinpei, and Katsu Kaishū. Also on board was Saigō Takamori; unfortunately there is no record of his feelings at this time.

A print by Utagawa Hiroshige III depicting the start of Japan’s first rail service, from Tokyo’s Shinbashi to Yokohama, in 1872. (Courtesy of the Minato City Local History Museum)

Train Tales

A first-class ticket from Shinbashi to Yokohama cost 1 yen, 12 sen, and 5 rin, while a second-class ticket cost 75 sen and a third-class ticket 37 sen and 5 rin. This was extremely expensive for the time—even riding third-class cost the equivalent of around ¥5,000 in today’s money. Fares went down in 1873 to 1 yen for first class, 60 sen for second, and 30 for third, but this was still far from affordable for most people. However, the eye-catching sight of trains puffing smoke and traveling over the sea was popular with woodblock artists, and attracted many tourists.

Artist Kawanabe Kyōsai imagined Japan’s first train en route to paradise. (Courtesy Seikadō Bunko Art Museum; © DNP Art Communications)

Various humorous tales remain that illustrate the unfamiliarity of Japanese people with this new form of transportation, such as lines of shoes being left behind on the platform as the train departed due to the habit of riders removing their footwear before boarding. There are also stories of people dousing the passing train with water in the belief that the smoke billowing from it meant it must be very hot.

There were no toilets, and many people relieved themselves from open windows instead. An 1881 news report in Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun stated that a former samurai from Nagasaki Prefecture pointed his backside out of a window and farted, whereupon he was fined 5 yen for the infraction.

Japan’s first steam locomotive is a nationally designated important cultural property. It was constructed in 1871, and began traveling between Shinbashi and Yokohama in 1872. (Courtesy the Railway Museum)

Private Expansion and Nationalization

In 1874, a new line connected Kobe to Osaka, and a route between Osaka and Kyoto opened in 1877. In 1880, Inoue Masaru applied his mining knowledge in construction of a tunnel through the Ōsakayama hills to link Kyoto to Ōtsu in Shiga Prefecture. While there were fatalities during this work, it was the first time Japanese engineers had built a tunnel without outside assistance. The Japanese government had dismissed its foreign engineers around this time to manage the railway using Japanese staff alone.

Japan’s first private rail company Nippon Railway was founded in 1881 using capital provided by members of the aristocracy. After the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, the government found it financially difficult to construct new lines, and so gave permission for foundation of the new company. The government’s Railway Bureau handled construction and management, as well as assisting with funding.

Nippon Railway began by building a line between Ueno and Kumagaya in Saitama Prefecture in 1883, before extending further north and adding other lines. It won success in transportation of raw silk and coal. More private railway companies were established from the late 1880s, and the total length of their lines outstripped those of the government in the 1890s.

However, Prime Minister Saionji Kinmochi enacted a law nationalizing the railways in March 1906. After the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War in September 1905, many soldiers and supplies were transported by train, but the mix of private and government-run railways meant that this was a complicated business. The military called for nationalization to make it a smoother process. Another important factor was that a unified rail network run by the state was good for industry.

Japan also built a railway in its colony of Taiwan, acquired from China after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. After the Russo-Japanese War, it further expanded to the Asian continent.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth, Japan took over parts of the Liaodong Peninsula that had been leased from China to Russia, administering them as the Guandong Territory. It established the Guandong Government-General at Lushun, and founded the South Manchuria Railway Company in 1906, a semi-governmental and semi-private company, to manage the Russian-established Chinese Eastern Railway between Changchun and Lushun, as well as coal mines along the line.

Thus, in a little over three decades since its first railway line began running, Japan had a rail network extending across the country, as well as lines in Taiwan and Manchuria, run by Japanese managers. In this sense, the development of the railway was a symbol of Japan’s modernization.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 30, 2022. Banner image: An 1874 picture of the steam train on the Yokohama coast by Utagawa Hiroshige III, who was among the many woodblock painters inspired by Japan’s first train. Courtesy Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History.)