“Kappa”: The Terror of Japan’s Rivers

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kappa are among Japan’s most famous yōkai. The supernatural creatures abound in manga, anime, and other entertainment, but also appear in television commercials and as promotional mascots for local authorities. This testifies to a powerful shared image in Japan of their appearance and characteristics.

Contemporary Japanese people typically visualize kappa as having green, hairless bodies shaped like that of a human child. They have smooth, circular dishes on their heads, with a kind of hair growing around it, and pointed beaks like birds, which are often yellow. On their backs, they have what looks like a turtle’s shell, and their hands and feet are webbed. Kappa live in rivers and ponds, where they catch hold of the feet of swimmers, dragging them to a watery death. Despite this monstrous activity, the kappa of today are often seen in cartoon form as cute and merely mischievous characters.

A standard image of a kappa. (© Pixta)

Edo Influence

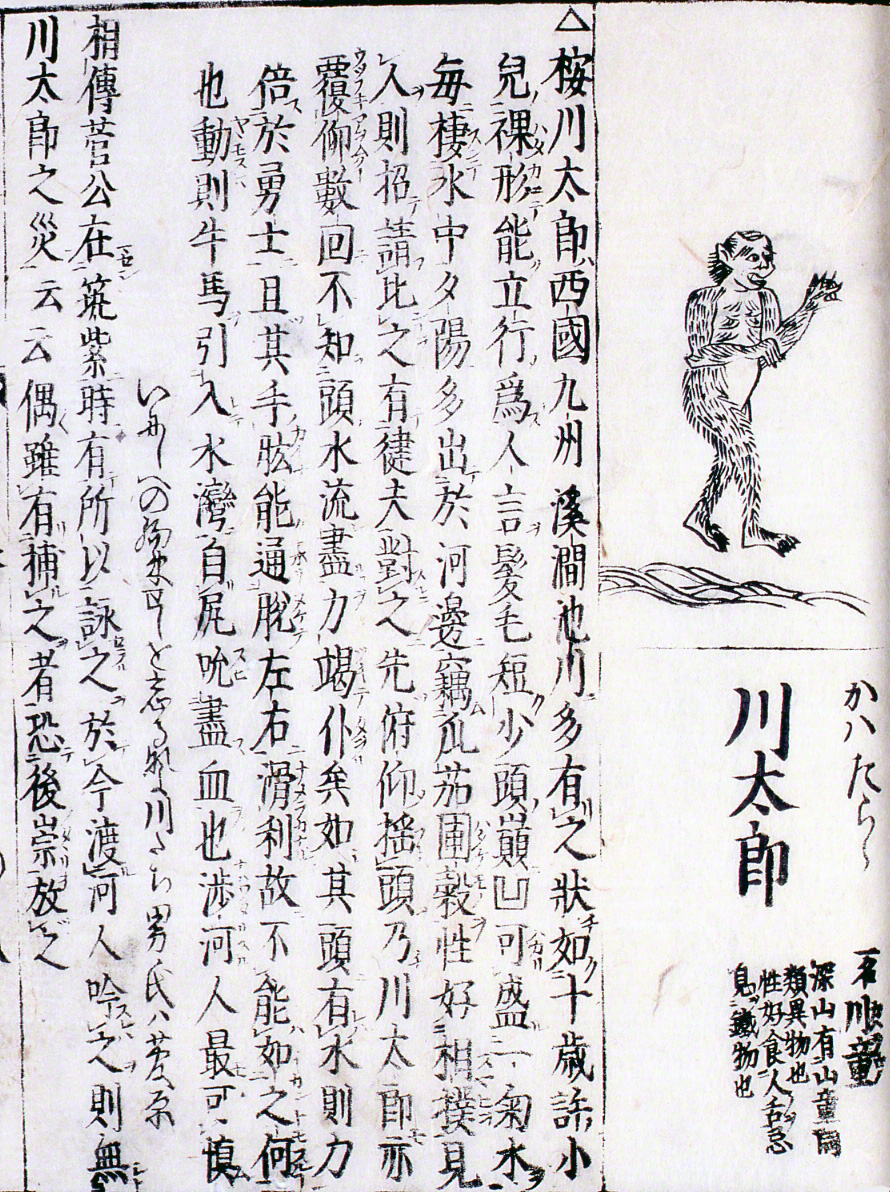

Today’s idea of a kappa only coalesced fairly recently, from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, and it is quite remote from former traditions. Even the names of the creatures themselves once varied by region. In the Edo period (1603–1868), they were known as kawatarō or gataro in the Kamigata area around Kyoto and Osaka. In Tōhoku, they were medochi, in Hokuriku mizushi, in Chūgoku and Shikoku enkō, and in Kyūshū hyōsube.

The kappa is introduced under the name kawatarō in the 1715 encyclopedia Wakan sansai zue (Japanese-Chinese Illustrated Assemblage of the Three Components of the Universe), and looks like a hairy monkey. Edited by Terajima Ryōan. (Courtesy Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of History)

Until the eighteenth century Kamigata was Japan’s cultural center. Thus, at that time documents used the term kawatarō, with kappa noted only as a regional variation. In the nineteenth century, however, the rise of woodblock printing gave Edo (now Tokyo) an unassailable lead in publishing, which brought with it a complete cultural shift. The Edo variant kappa now became mainstream, just as Tokyo dialect became standard Japanese in modern times.

A Changing Image

Kappa were also thought of as mammals like monkeys or otters until the eighteenth century, rather than reptiles or amphibians. The fifteenth-century dictionary Kagakushū (Collection of Low Studies) describes how when otters become older, they turn into kawarō, which is the oldest reference on record to kappa. The term kawarō for kappa is also found in the Japanese-Portuguese dictionary compiled by Jesuit missionaries in Nagasaki in 1603; it is defined as a monkeylike creature that lives in rivers.

In the nineteenth century, however, kappa with turtle shells became predominant. Just as with the word kappa, this was due to Edo influence. Buoyed by printed materials, and especially visual media like ukiyo-e prints, what was once a minor variant nationwide soon established a new standard.

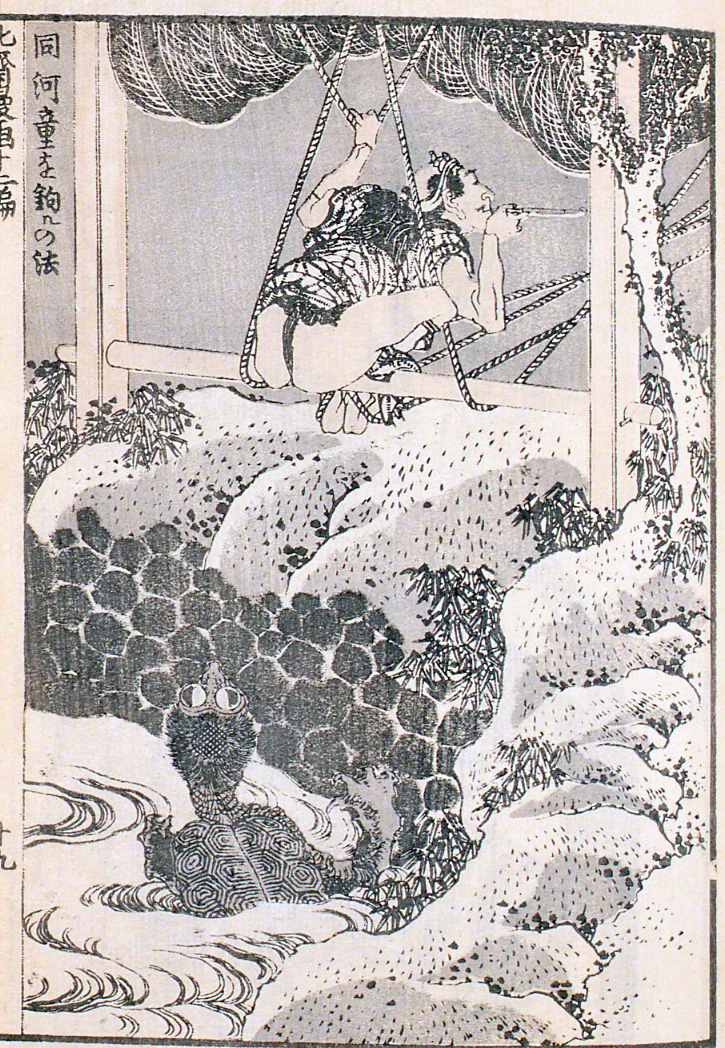

For example, Katsushika Hokusai followed Edo conventions in depicting kappa with pointed beaks, as well as shells and bodies like different kinds of turtle, in his Hokusai manga (Sketches by Hokusai) picture books. Other ukiyo-e artists would sometimes color kappa bodies green, perhaps due to an association with frogs. There is almost no evidence of previous traditions for green kappa or connections with the amphibians, but their webbed feet and similarity in outline to young children, apart from the head, suggest that some artists chose frogs as convenient models for the imaginary creatures. The main point I would like to stress here is that Edo-period ukiyo-e are the reason that people now think of kappa as green.

A kappa (bottom right) modeled on a turtle in Katsushika Hokusai’s Hokusai manga (Sketches by Hokusai). (Courtesy Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of History)

Cuter Kappa

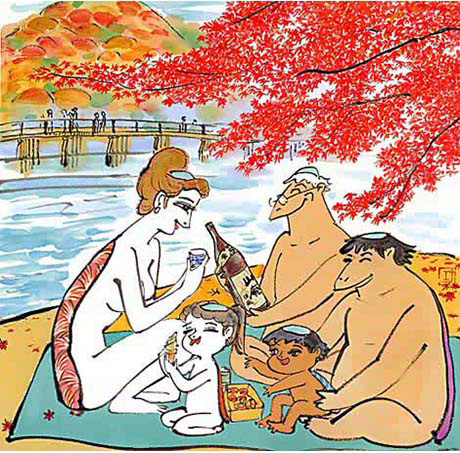

In the Edo period, kappa and other yōkai were characters in the illustrated books (kusazōshi) that were the equivalent of today’s manga. They were depicted as comical figures, with their original terrifying nature, as seen in their tendency to drown unwary humans, considerably toned down. While this was one stage in the development to the contemporary kappa, it was not until the 1950s that the creatures were portrayed as straightforwardly cute. Shimizu Kon’s manga works Kappa kawatarō and Kappa tengoku (Kappa Heaven) were massive hits that instigated a kappa boom. His endearing version of the water-dwelling yōkai became a mascot for Tokyo Citizen’s Day on October 1 each year, and also appeared in commercials for snacks and sake. Shimizu’s characters were instrumental in creating a kawaii image for kappa.

Shimzu Kon’s Kappa kawatarō, centered on a kappa child, was the first work to portray the yōkai as cute. (Courtesy Nakanochaya Shimizu Kon Exhibition Hall, Nagasaki)

Kappa characters created by Kojima Kō in a commercial for sake brewery Kizakura. The company previously used Shimizu Kon’s kappa in its commercials. (Courtesy Kizakura)

A Terrifying Past

The transformation of the kappa via mass media has made it into a very different beast from its traditional forebear, particularly in the loss of its nightmarish reputation. Kappa were once said to drag humans, cattle, and horses into the water and devour their inner organs and shirikodama (a mythical ball inside the anus). They would also rape women and force them to have their children, and drive people mad or make them sick.

A kappa in Hokusai manga (Sketches by Hokusai), modeled on the Chinese softshell turtle. The man is luring the kappa by sticking out his backside, knowing it will be tempted by his shirikodama. (Courtesy Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of History)

In folklore, kappa are commonly said to enjoy sumō, and this may seem superficially charming, but not if they pull defeated humans beneath the water, or otherwise harm them.

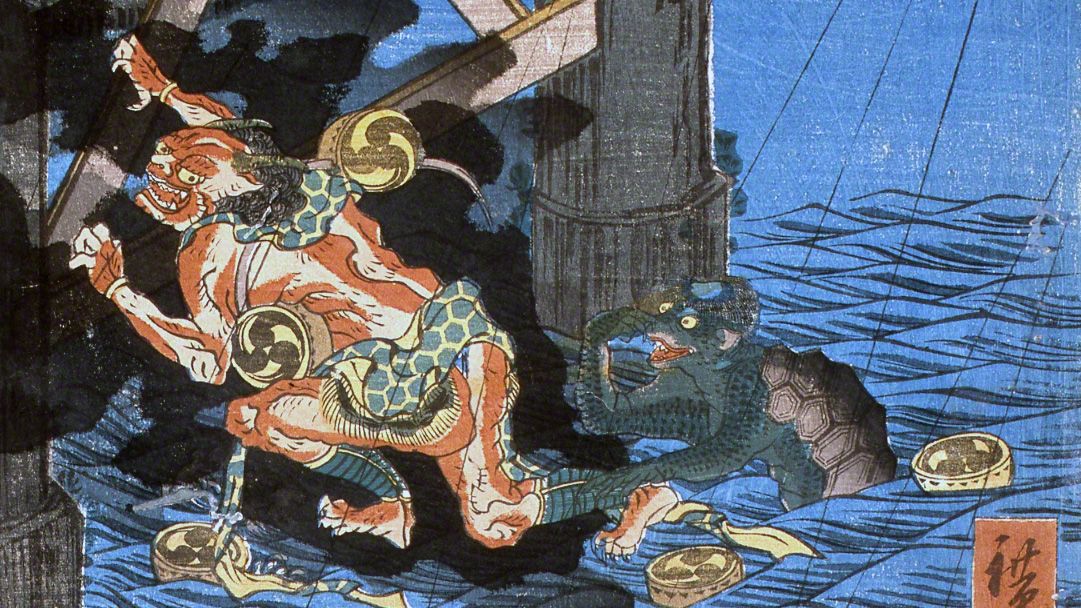

Utagawa Toyokuni, Kazusa: Shirafuji Genta from the Dai Nippon rokujūgoshū no uchi (Sixty-Odd Provinces of Japan) series, 1843–47. The legendary Edo-period sumō wrestler Shirafuji Genta captures a kappa. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

Revered at Shrines

Even these frightening yōkai could sometimes bring people benefits. One legend in a number of areas tells of a kappa that had its hand chopped off after touching a woman’s bottom while she was in the toilet. In exchange for receiving the hand again, the kappa shared the secret of how to make a miraculous medicine. In another kind of story, a kappa tries to drag a horse into the water, but is itself pulled up onto land. It is only forgiven after swearing it well never try to drown the villagers again. With the latter kind of story, there are sometimes records of the creature’s promise, or in some cases, it is celebrated as a water kami or deity.

Kahaku Shrine in Nankoku, Kōchi Prefecture, has a kappa festival each year, based on the story of a kappa saved by the head priest of the shrine after it was caught trying to pull a horse into the river. It promised not to drown the people of the village in the future and became celebrated as a kami. (© Kagawa Masanobu)

These stories are reminiscent of Japan’s ancient legends from the age of gods, with the kappa as a kind of natural spirit. The Japanese people of that day were in awe of nature, and they sought to gain a measure of control over its threats by giving it concrete form as kami or yōkai. The kappa represented the terrors of nature in the form of rivers, ponds, and the sea. It only needed one mistaken act for even the best of swimmers to drown. Kappa were invented to caution against carelessness.

Today, “No Swimming” signs beside rivers and ponds often include illustrations of kappa. Despite their cute appearance, they convey the same warning.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 30, 2022. Banner image: Utagawa Hirokage, Edo meisho dōgezukushi [Comic Incidents at Famous Edo Locations], 1859. A kappa, at right, tries to pull a thunder god, which fell down from the sky, into the water at Ryōgoku Bridge. Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu.)