“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

“Mizuhiki”: Fourteen Centuries of Artistic “Ties that Bind”

Culture Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Long and Twisted History

Mizuhiki, art made with twisted washi paper cords, has a long and fascinating history. There are many theories concerning its origin, but it dates back to at least the Asuka period (583–710). Its first appearance in Japan is said to have been red-and-white decorative hemp binding used to tie up gifts brought back to Japan by envoys to Sui dynasty China (581–618). The modern style of mizuhiki, where washi is twisted and stiffened with glue, had developed by the time of the Muromachi period (1333–1568).

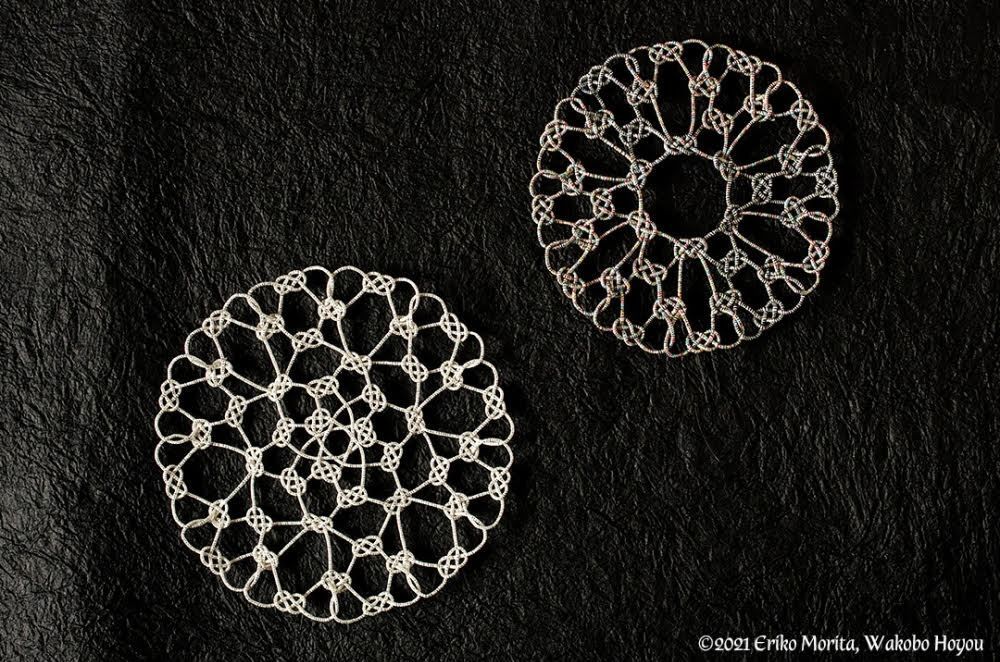

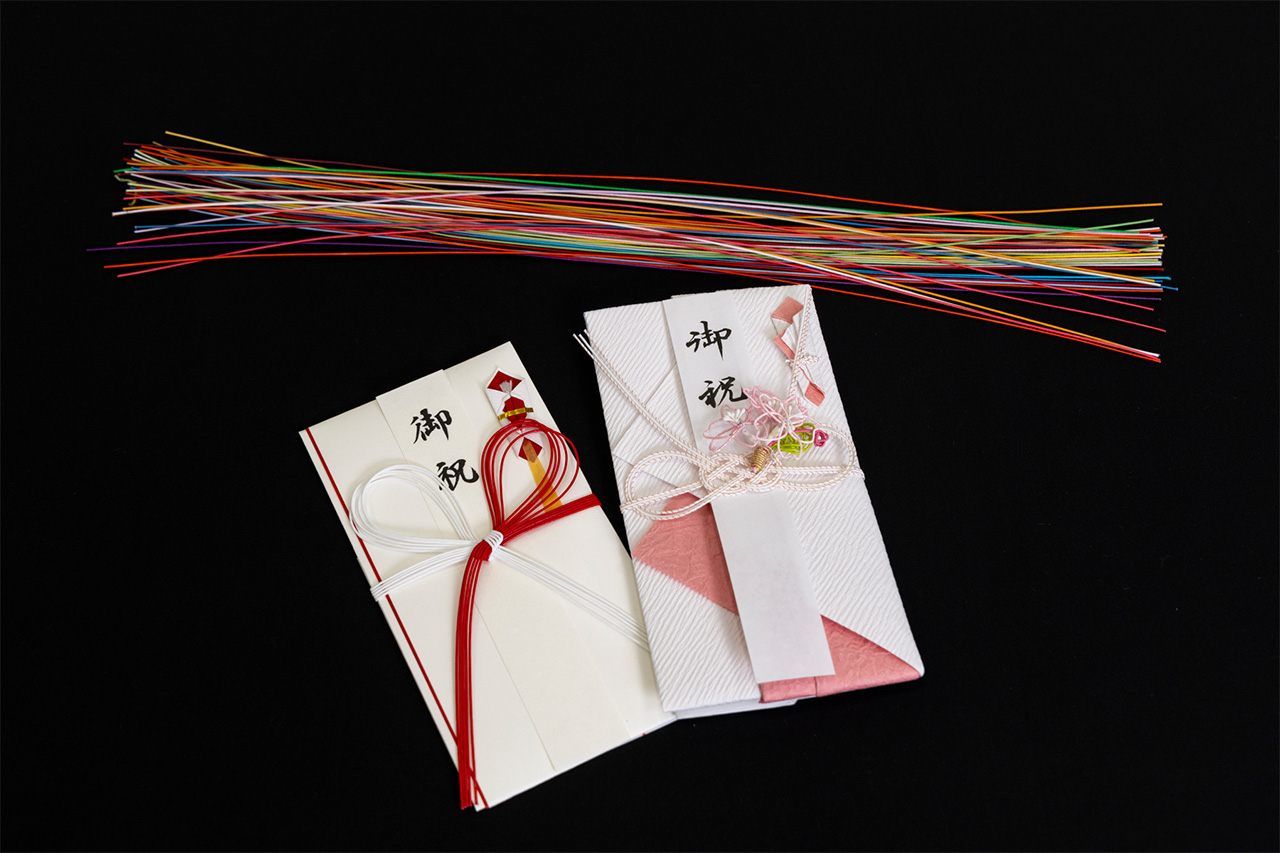

Most Japanese people have seen mizuhiki cords used to decorate envelopes for monetary gifts. They are layered upon one another to create the common hana-musubi (flower tie) at left; at right is an intricate awabi-musubi (abalone tie) crafted by Morita Eriko. (© Kawamoto Seiya)

According to mizuhiki artisan Morita Eriko, “Mizuhiki is also used in Shintō religious ceremonial items. It was practiced by the aristocracy until the Edo period (1603–1868), when it spread to the general populace. In the Meiji era (1868–1912), it became customary to give monetary gifts, and special envelopes were designed for the purpose. In those days, mizuhiki was taught to girls at school. Also, recently, the variety of mizuhiki cord colors has expanded beyond the traditional red and white used in festive situations or black cord used with funeral offerings. Now, it is more accessible and has greater possibilities than when I began mizuhiki.”

Morita first encountered the craft in 2006, and began working as an artist a year later. She started a studio named Wakōbō Hōyū in Kyoto, both for her own creative work and to teach others in order to share the beauty of mizuhiki.

“Incorporating colorful designs into the tradition of mizuhiki has enabled me to connect with younger people,” says Morita. “Even just adding mizuhiki to an envelope helps convey the true feelings of the sender.” (© Kawamoto Seiya)

Endless Possibilities in Three Dimensions

Morita’s creations are charming and never bound by convention. Her works depict Japanese seasonal events, flowers, and even sweets—you could almost forget they are not real.

Floral designs are popular with mizuhiki novices. Clockwise from left: Delicate mizuhiki strawberries, playful Daruma figures that Morita designed for Year of the Dragon, and a colorful café-style “pudding à la mode.” (© 2021 Eriko Morita, Wakōbō Hōyū)

Morita was initially drawn by the beauty of mizuhiki, at a time when there was only one place in Tokyo where she could study the craft. Since then, her kawaii works have generated wider interest in mizuhiki and have inspired many people to try it themselves.

Morita says: “One thing that surprised me when I first started to learn the craft is that, no matter how complex the design may appear, it is possible to create it by simply applying the basic techniques. I use everyday objects in my designs: Even when I’m eating, I get inspiration from what’s on my plate. There’s no limit to the things I want to make.”

Morita showed us how to make a simple ume-musubi (plum tie). The resulting “plum petal tie” would be a lovely surprise included with a letter or even attached to the outside of the envelope.

(Video) How to Tie a Ume-musubi (Plum Tie)

First, make a basic “abalone tie,” then pass both ends through the center hole to create a “plum tie.” The trick is to line each strand up one at a time while ensuring that they don’t overlap or get twisted. (Video © Kawamoto Seiya)

Using more strands produces a bigger finished piece. Five strands are used to make a large one, or three for a small one. More strands also increase the level of difficulty. (© Kawamoto Seiya)

Mizuhiki strands are not elusive art supplies; they are even available at 100-yen shops. The standard length is 90 centimeters, but strands cut into 30-centimeter lengths are also common. In addition to plain colors, you can find strands woven together with gold or silver thread. Mizuhiki comes in hundreds of colors, offering limitless combinations to express yourself.

A gorgeous garland of yellow mimosa flowers. (© Kawamoto Seiya)

According to Morita, the “abalone tie” (awabi-musubi, sometimes called awaji-musubi) is the basis for making both flat and three-dimensional mizuhiki in any shape, from sushi that fit in the palm of your hand to creations 5 meters across. It is surprising how versatile a single strand of mizuhiki can be. Morita does not use patterns to produce her creations. For her, the thrill comes in visualizing the finished product and letting her hands do the rest.

Sushi made using the basic “abalone tie.” (© Kawamoto Seiya)

Manekineko and Daruma (a lucky cat and a tumbling Bodhidharma doll), also made with the “abalone tie.” Morita visualizes the finished piece as she works. (© Kawamoto Seiya)

For Morita, the fascination of mizuhiki is more than just its decorative value. She explains some of its deeper significance:

“The awabi is a reference to abalone, a valuable ingredient used in religious offerings traditionally. In addition, mizuhiki on gift envelopes are made from five strands, the same as the number of fingers on one hand, representing the joining together of hands. There are meanings behind just about every facet of the craft. A person intrigued by mystical things, as I am, would find mizuhiki interesting in that regard.”

Morita holds part of a 5-meter-long mizuhiki creation. (© 2021 Eriko Morita, Wakōbō Hōyū)

Morita is still gradually extending this piece. “I enjoy the moments when I can be totally absorbed in mizuhiki.” (©2023 Eriko Morita, Wakōbō Hōyū)

Mysterious Links Between Mizuhiki and Celtic Designs

Morita was always attracted by patterns formed from the lines in Japanese brush calligraphy, and even before she first encountered mizuhiki, she was fascinated by traditional patterns from around the world. Later, when she began learning mizuhiki, she noticed that the “abalone tie” resembled a traditional Celtic motif.

Celtic designs made with mizuhiki. (© Eriko Morita, Wakōbō Hōyū)

“When I looked deeper into traditional designs from other cultures, I discovered similar patterns not only in Celtic culture, but also in arabesque forms, Turkish designs, and art nouveau. Such designs, formed from a single strand, may have arrived in Japan via the Silk Road in ancient times.”

Mizuhiki inherits a Japanese tradition of “binding,” yet it could also be tied to cultures from far away. Morita hopes to share around the world to expand opportunities for cultural exchange, and therefore she welcomes visitors who come to Japan interested in learning mizuhiki.

There are many more things she still aspires to create. “One day, I hope to make clothing with mizuhiki.” Her creations prove that, even after 1,400 years, the traditions of her art still have fresh potential.

Wakōbō Hōyū offers classes year-round in Kyoto, Osaka, Hyōgo, Nagoya, Tokyo, and online. For more details, visit the studio website: https://mizuhiki-houyou.jp/en/

Morita also posts her creations on Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/wakobo_hoyou/

(Originally written in Japanese based on an interview by Taguchi Mikiko. Banner photo: Morita’s mizuhiki sushi looks almost good enough to eat. © Kawamoto Seiya.)