Sake as International Phenomenon

Food and Drink Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Sake Going Global

Rice kōji mold and kōji’s role in fermentation is fundamental to sake brewing. (© Jim Rion)

In the six or so years since I first began seriously looking at sake, the drink has become a truly international one. Even setting aside the ever-growing export numbers, one only has to look at the flowering of international sake certification classes and specialist shops across the world, and above all, the incredible increase in people tasting, learning about, and even trying to make the drink, to see that sake is a global phenomenon.

Within Japan, international sake brewers are an increasingly common sight, from the first non-Japanese tōji head brewer Philip Harper at Kyoto’s Kinoshita Brewery (maker of Tamagawa sake), to those still working away at the lower level kurabito jobs like the Shimane Prefecture Itakura Shuzō’s Giulia Maglio, who also works as a sake educator via her outreach project Jijisake. There are also breweries opening up around the globe, from Mexico to Taiwan, Canada to New Zealand.

An international crowd showed up to a Tokyo event celebrating the release of the author’s book, Discovering Yamaguchi Sake. (© Jim Rion)

What is it about sake that is inspiring this international love affair?

As an American who fell in love with sake, and as someone who has been trying to educate international drinkers about it for years, I have a couple of ideas. First is its diversity.

For something made from such a simple ingredient list: rice, rice kōji—rice inoculated with the mold Apergillus oryzae—water, and yeast, the flavor range is mind boggling. You can get creamy sweet brews reminiscent of vanilla custard or delicate drinks with the scent of tropical fruit. Aged sake can bring the heft of whisky and notes of almond, caramel, and mushroom that you’d expect from a dry sherry, while fresh pressed and unpasteurized namazake can have the zippy sharpness of a tart green apple. There is sake that refreshes like water, or sake that lingers with honeyed sweetness. It is a drink that offers a breadth of experience that never grows old.

And that‘s just the flavor profile—the drinking experience is another source of endless experimentation. Sake can be drunk chilled, hot, or in between. It offers a different face when drunk from a glass or from a handmade ceramic cup. The same bottle can be a totally different beast a week after it has been opened. Sake is a drink with a thousand different faces, and curious drinkers can spend years without tiring of the exploration.

The Perfect Meal Drink?

Along with that diversity comes the simple fact that, throughout its long history, sake has primarily been a drink to go with meals. Given the somewhat subdued flavor palette of Japanese cuisine, the target of sake brewing has often been something that melds with and enhances that cuisine. Thus, it is by and large free of harsh, bitter notes or particularly strong acidity that might overpower Japanese food. This also makes it very easy to match to food outside Japanese cuisine.

As sake becomes more international, it is also becoming more common in luxurious settings. Even in Japan, as at the elegant Yamaguchi restaurant Chikuro Sanbō, sake is often served in wine glasses alongside international foods like pâté de foie gras and caviar. (© Jim Rion)

Pairing food and drink is a popular topic in the wine world, and recently also in sake, but it truly is more of an art than a science. Each person has their own tastes and perceptions, and I have drunk with many people who simply do not experience flavors the way I do. That being said, through dozens of tasting events with people from all over the world, I have almost never seen any food pairing with sake that just didn’t work.

In an online event exploring the ways that Hyogo Prefecture brewing behemoth Kenbishi sake paired with different overseas food, drinkers from the United States, Australia, and Japan all agreed that fermented food like white-mold salami or sharper cheeses like aged cheddar or gouda all went perfectly with warmed Kenbishi. One member enjoyed this rather richly flavored brew with Chinese spring rolls, as well, while a Swiss participant highly recommended it with avocado.

The Coronavirus pandemic drove many sake events online, but it did not stand in the way of this Kenbishi sake pairing. (© Jim Rion)

Such international pairing exploration is not unusual these days. One colleague in sake education, Arline Lyons, lives in Switzerland and hosts popular sessions exploring how sake pairs with different types of chocolate, while here in Yamaguchi, there is a specific project pairing sake with Chinese hotpot dishes.

I once hosted a sake event for visitors from Eemsdelta, the Netherlands, to Shūnan, Yamaguchi Prefecture. The group had almost no experience at all with sake, making this an important chance at a first impression. I arranged a short presentation on basics, because understanding deepens enjoyment, then offered a variety of local sake to go with a primarily Western-focused menu of meats, cheeses, breads, and some local noodle dishes. The clear ease with which the local sake matched such a wide variety of food made an impression, and several visitors announced their newfound sake fandom would be going back to the Netherlands with them.

Local sake is even showing up in international diplomacy, as in this gift pack of Hiroshima brews shared at the G7 2023 Hiroshima Summit meeting. From left, Otafuku Junmai Ginjō from Tsuka Shuzō, Hakukō Tokubetsu Junmai from Morikawa Shuzō, and Oigame Junmai from Ono Shuzō. (© Jim Rion)

On a purely personal level, for several years I tried sake with basically every dinner I had. Pizza, tacos, mapo tofu, hamburgers—I’ve explored them all, and each one revealed a different way that sake brings out some flavors and masks others, giving birth to new experiences with each meal.

It seems clear, then, that sake goes with more than sushi and sashimi. It is simply a fantastic meal drink.

However, there are no universals in life. You might find that some sake you enjoy fails to stand up to some of your favorite meals. Many of the more expensive brews on the market are made specifically for enjoying them as themselves, so they have delicately balanced aromas and crystalline flavors that could be muddied or even overpowered by most food, for example.

So, a couple of rules of thumb I’ve found for sake pairing. First, low- to mid-market sake, like your basic junmai, honjōzō, or even the ubiquitous futsūshu, are the least likely to have overly assertive aromas or flavors that can make pairing difficult. Second, don’t overchill sake. Cold temperatures can hide or subdue many flavors, so let your sake rest for 20 or so minutes out of the fridge or even heat it up to let the flavors open up and express themselves.

But all of this must come with a disclaimer: My palate is not yours, so the only way to actually know how a given sake pairs with a given food is to try it yourself.

A Basic Guide for Buying and Drinking Sake

For those who want to take that advice to heart, there are a few terms that could come in handy in exploring sake. You might see them on labels or in various sake adjacent spaces—not to mention in this article—and they can indicate something useful about the sake.

An array of Yamaguchi sake that won international fans at the author’s book release party. From left, Nishikisekai Junmai Daiginjō from Takeuchi Shuzōjō, Yamazaru Daiginjō from Nagayama Shuzō, Nakashimaya Muroka Ginjō and Kanenaka Kimoto Junmai from Nakashimaya Shuzōjō, Ikuyamakawa Junmai from Kinfundō Shuzō, and Nishikisekai Genshu from Takeuchi Shuzōjō. These run the gamut from futsūshu to daiginjō. (© Jim Rion)

Futsūshu – This is almost never seen on labels, but it is a common term. It indicates the largest single “class” of sake, a generalized group akin to table wine. Literally meaning “regular sake,” it can feature a wider range of ingredients than those allowed in the more premium groups, which have strict labelling laws related to production methods.

Ginjō/Daiginjō – The term ginjō is legally defined and, although a variety of standards are applied, for the consumer indicates a sake that has been made with great care and highly polished rice, reducing many of the coarser elements and raising the drink’s refinement and fruity expressions. Daiginjō indicates an even greater refinement and more highly polished rice.

Honjōzō – Another legally defined term, this sake indicates sake made from rice polished to 70% its original size and made with a small amount of pure brewer’s alcohol added to the sake near the end of fermentation to lighten flavors and bring out aromas.

Junmai – A legally defined term that indicates a sake that was made without any ingredients other than rice, rice kōji, yeast, and water. It stands in opposition to honjōzō, which has added brewer’s alcohol, and futsūshu, which can have additions like sugar, brewer’s alcohol, or acidifiers.

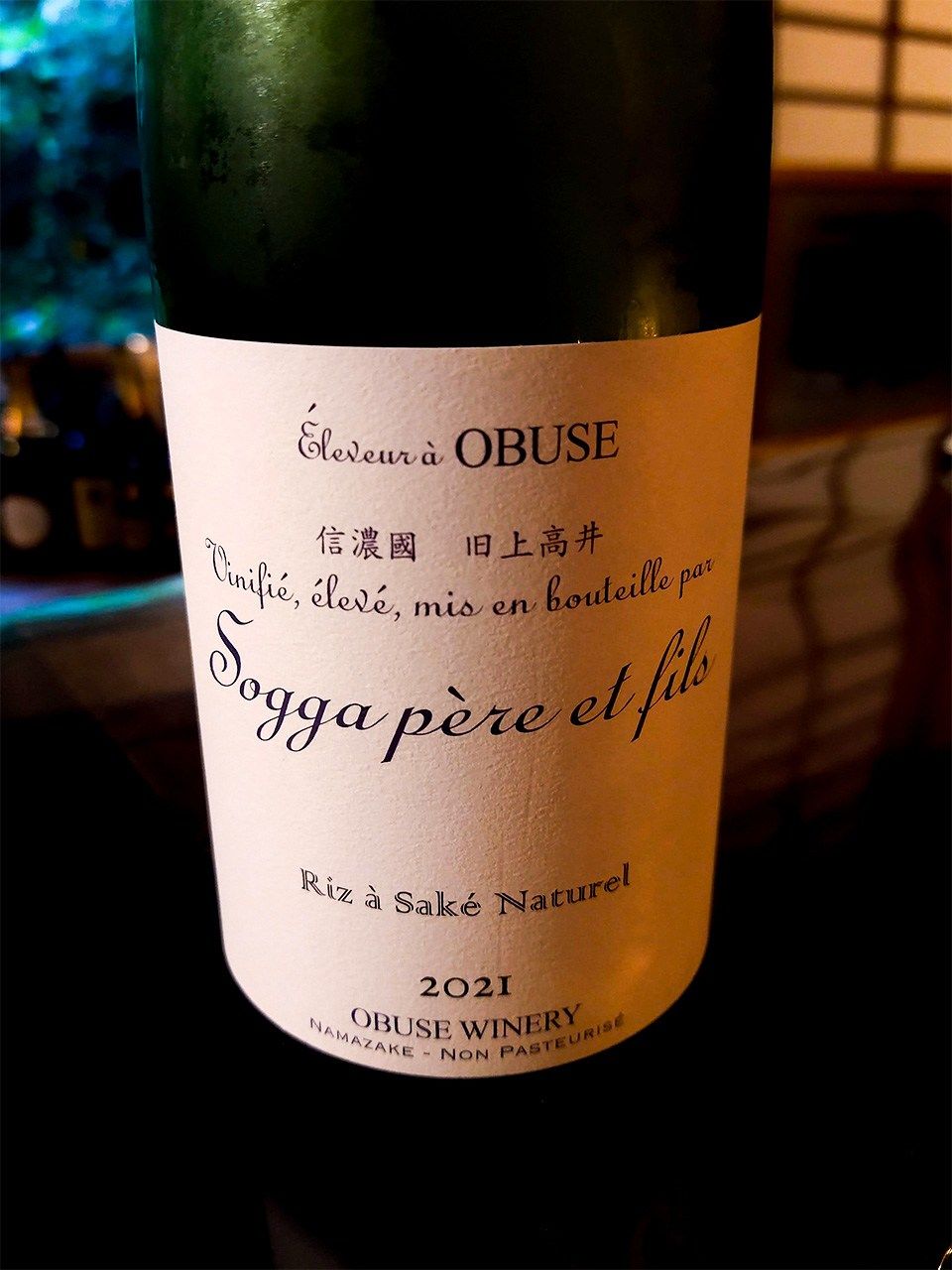

Namazake – A general term for sake that has not been through one or both of the two usual pasteurization/heat treating processes that sake usually undergoes. Namazake is usually sold quite fresh after pressing, so it can have much more lively or even brash flavors.

Sogga père et Fils from Obuse Winery is a legendary namazake. (© Jim Rion) (© Jim Rion)

The best way I’ve found to make use of this knowledge is to try a few sake varieties from a shop menu based on, say, staff recommendations and then look at the labels for any that you liked. See which words were used on the label or in descriptions and take note for future exploration.

With those notes in hand, you are now ready to start exploring this fundamental part of Japanese dining and social culture. Kanpai!

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: A selection of sake presented to participants at the G7 Hiroshima Summit in 2023. © Jim Rion.)