Capital Punishment: Japan’s Pause in Executions Extends for More than Two Years

Society Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

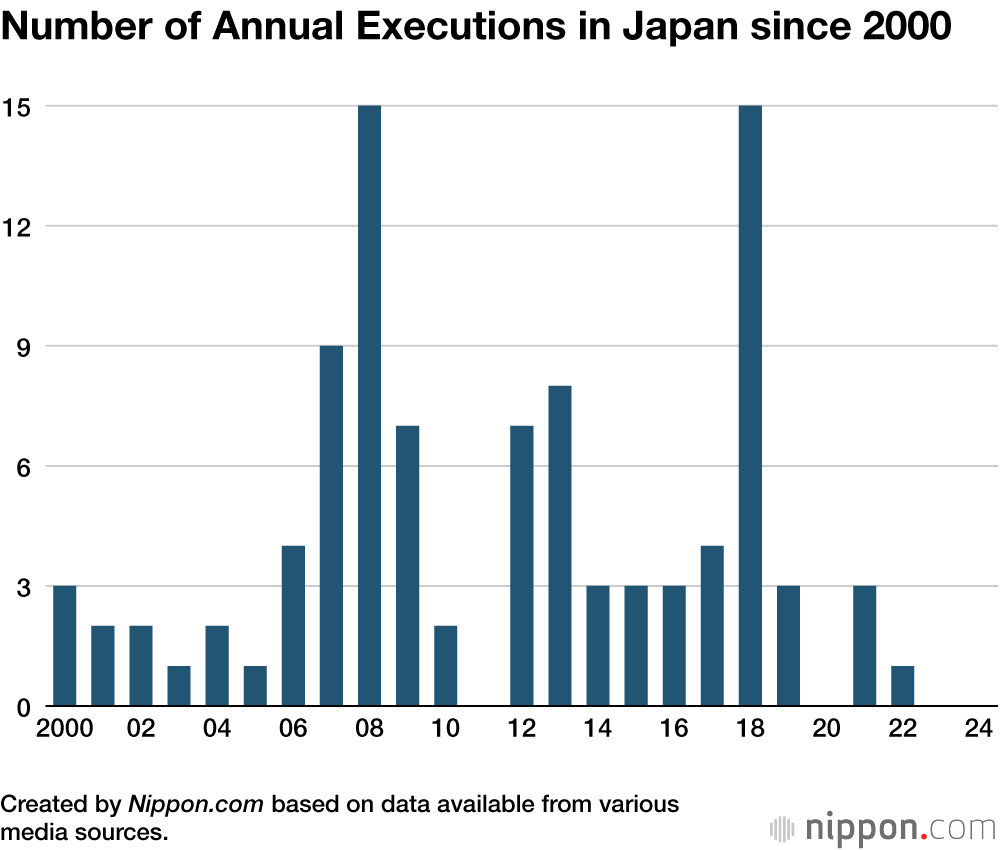

Two and a half years have passed since Japan last carried out the death penalty. The most recent case was the execution of Katō Tomohiro on July 26, 2022, for a 2008 stabbing spree that left 7 people dead and 10 injured in Tokyo’s Akihabara district. There have been previous pauses on executions, such as the year of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 and the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, but this is the first time this century for two calendar years to go by without a prisoner being put to death.

Japan’s Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates that the death penalty should be implemented within six months of the issuing of the sentence, but in fact this is almost never the case. From the beginning of 2000 to July 26, 2022, 98 death sentences were carried out. The shortest time span from sentencing to execution was 1 year, while the longest was 19 years and 5 months. The Ministry of Justice does not clarify any of the criteria on which the decision to execute a prisoner is based. In fact, in the past it was policy to not even publicly announce that an execution had been carried out. Disclosure of information on executions and the number of those executed only began in October 1998, under the direction of Minister of Justice Nakamura Shōzaburō. In September 2007, the justice minister of the time, Hatoyama Kunio, instructed the ministry to also release the name of each executed convict and the place of execution.

Decisions about executions seem to reflect the thoughts and feelings of the minister of justice of the time. Sugiura Seiken, upon being appointed to that post in October 2005, for instance, openly declared that he would not issue an execution order on religious and philosophical grounds. Although he soon retracted the statement, amid criticism questioning his right as justice minister to refuse to carry out a duty stipulated by law, he did not end up signing an execution order during his tenure of roughly 11 months. Contrasting with Sugiura’s attitude were the cases of those ministers who signed execution orders at the rapid pace of one every few months.

Only nine people were executed from September 2009 to December 2012 under the administrations of the Democratic Party of Japan, whose justice ministers showed reluctance to carry out the penalty. Chiba Keiko, the DPJ’s first justice minister, was originally opposed to the death penalty and had been one of a group of Diet members who called for its abolition. In July 2010, however, she signed the order to execute two death-row prisoners. Chiba witnessed the executions—a first for a Japanese justice minister—and expressed her desire that they should serve as an opportunity for a national debate over the death penalty. Toward that end, she set up a study group within the ministry to consider whether it should continue. In August of the same year, Chiba opened the Tokyo Detention House’s execution chamber to the media for the first time, as well as the room it provides for prisoners to meet with religious representatives.

Eda Satsuki, who was appointed justice minister in January 2011 under the DPJ government of Prime Minister Kan Naoto, stated at a press conference soon afterward that “capital punishment is a flawed penalty”—although he later retracted the statement. In July of that year, Eda expressed his intention to not sign any execution orders for the time being since the study group on the issue established by Chiba was still meeting. That year no executions were carried out. The study group continued to meet under the next justice minister as well, but it convened for the last time in March 2012 without reaching any final conclusion, merely registering the various opinions expressed on both sides of the issue.

When Japan introduced trial by jury in 2009, members of the public became involved in capital punishment decisions. In 2017, there was a string of executions of prisoners who were petitioning for retrial. Criticism was also raised inside and outside Japan in 2018 over the execution of 13 prisoners connected to the Aum Shinrikyō cult in the space of a few weeks.

A recent high-profile case concerns Hakamata Iwao, who was sentenced to death in 1980 for the killing of four people in 1966. He maintained his innocence from prison and in 2014, Shizuoka District Court released him and granted him a retrial. The retrial began in 2023 and concluded in September 2024, with the court acquitting Hakamata after finding that investigators had fabricated evidence. The ruling came 58 years after his original arrest and 44 years after he was sentenced to death. Having been incarcerated for so many years with the death penalty hanging over him, Hakamata, even a decade after his release, has difficulty communicating with others.

This story has put the spotlight on capital punishment, sparking calls for reform. A panel including lawmakers, a former prosecutor general, and a former commissioner general of the National Police Agency released a statement on November 13 calling for a halt on executions until authorities rethink the government’s approach to capital punishment and institute fundamental changes to the system.

As of the end of 2024, there were 106 death row prisoners in Japan.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: The Tokyo Detention House, which contains an execution facility. © Pixta.)