Survey in Japan Reveals Discrimination Against Hansen’s Disease Patients Persists

Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare recently conducted the first nationwide survey on prejudice and discrimination against former Hansen’s disease (leprosy) patients and their families. The published report noted that “prejudice and discrimination continue to exist and remain serious problems” as a result of the inadequate degree of knowledge within Japanese society regarding the condition.

Hansen’s disease is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae, also known as the “leprosy bacillus.” It leads to loss of sensation in the peripheral nerves in the hands, feet, and other parts of the body, as well as various pathological symptoms on the skin. The contagiousness of the leprosy bacillus is very low, and with early detection and appropriate treatment the disease can be cured without any residual aftereffects. Since the early twentieth century, the Japanese government has adopted a policy of isolation for persons infected with the disease, forcing them to stay in sanatoriums. In addition, patients and their families were subjected to prejudice and discrimination. Patients were also subjected to sterilization and abortion procedures under the former Eugenic Protection Law. The Leprosy Prevention Law, which promoted the segregation of patients, was not repealed until 1996, finally ending the policy of segregation.

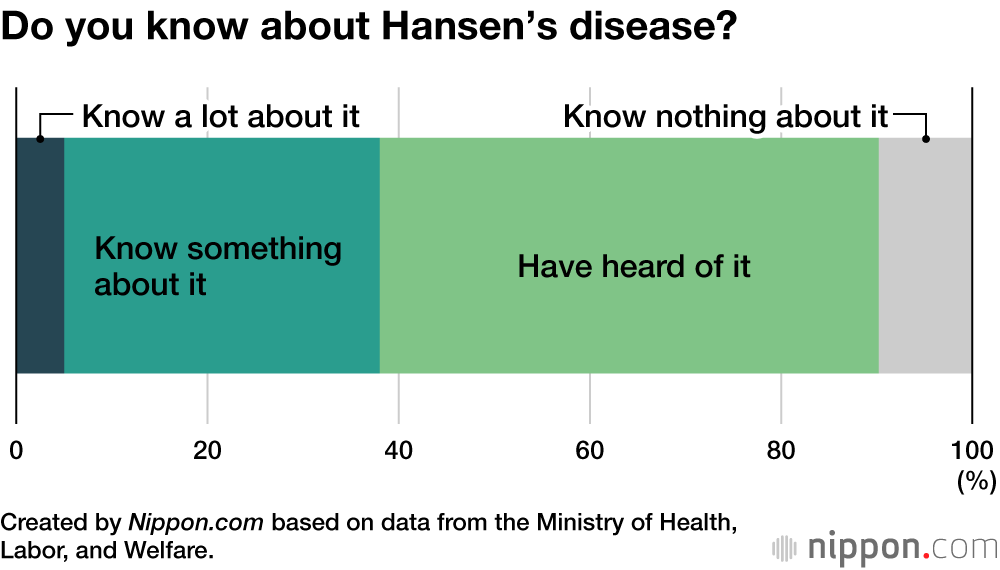

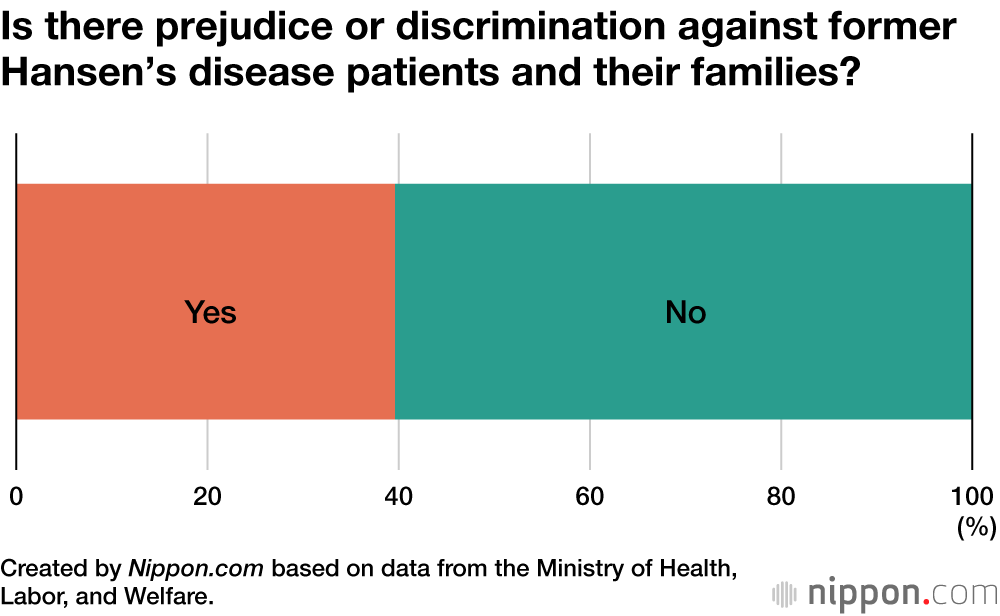

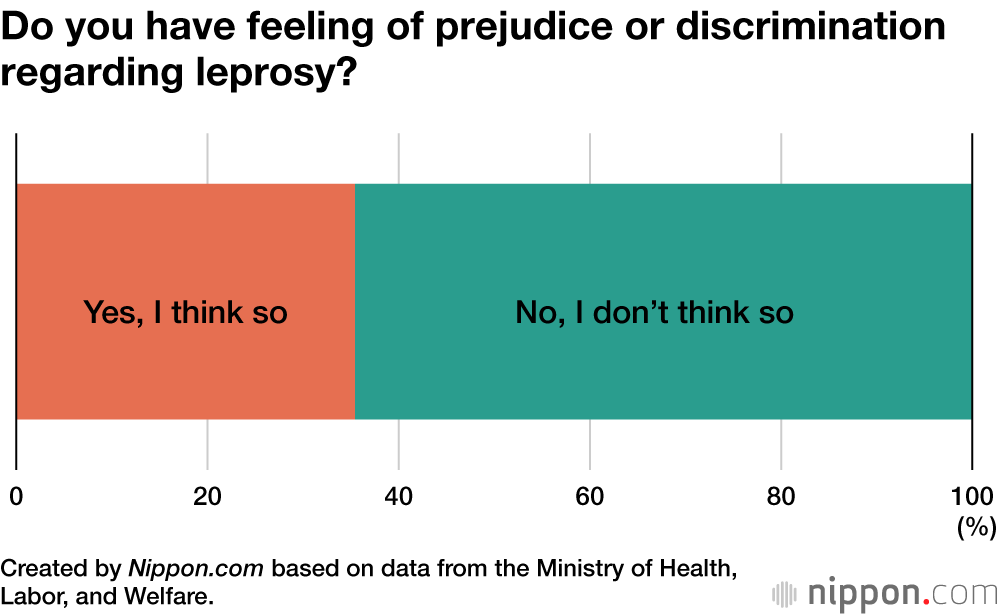

According to the Ministry’s report, 38% of the survey respondents said they knew about Hansen’s disease and another 52.2% that they had heard of it, for a total of around 90%. Meanwhile, 9.8% of the respondents said that they knew nothing about it. Regarding prejudice and discrimination against former patients and their families, 39.6% of the respondents said that they thought such attitudes still exist in the world, while 60.4% said that they did not think prejudice and discrimination still existed. In response to the question of whether they themselves felt some sense of prejudice or discrimination against people with leprosy, 35.4% said they did, while 64.6% said they did not.

Nine of the survey questions concerned potential interaction with former patients and their families. With regard to the five questions concerning everyday contact (including living in the same neighborhood, being employed at the same workplace, or attending the same school), less than 10% of the respondents described themselves as “very resistant” or “somewhat resistant.” However, there was greater resistance to having a meal together (12%), coming into personal contact such as holding hands (18.5%), using the same bath at a hotel or some other location (19.8%), and having a family member marry a family member of a former patient (21.8%).

For all nine survey questions, those who had studied about leprosy in elementary, junior high school, or high school actually tended to show a higher level of resistance than others. They were also more likely to agree, at least somewhat, with the mistaken argument that the forced isolation of leprosy patients in sanatoriums had been an unavoidable measure, even after a cure had been introduced.

The ministry’s report concludes that the education and awareness-raising efforts of the government seem to be “barely reaching the public.” It calls for urgent examination of current activities so as to improve the situation. The nationwide survey was conducted online in December 2023, with a total of 20,916 responses received.

A movement to provide aid to former leprosy patients was launched in response to the Kumamoto District Court ruling in 2001, which declared the segregation policy unconstitutional and ordered the government to pay compensation for damages. The court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, made up of former patients. The government did not appeal the ruling, so that it was finalized as law, leading to the introduction of a system to provide aid. In 2019, the Kumamoto District Court ordered the government to compensate the family members of former patients for the discrimination they had suffered as a result of the isolation policy. The government made the political decision to not appeal the ruling, so that a law was enacted to compensate damage suffered by the family members.

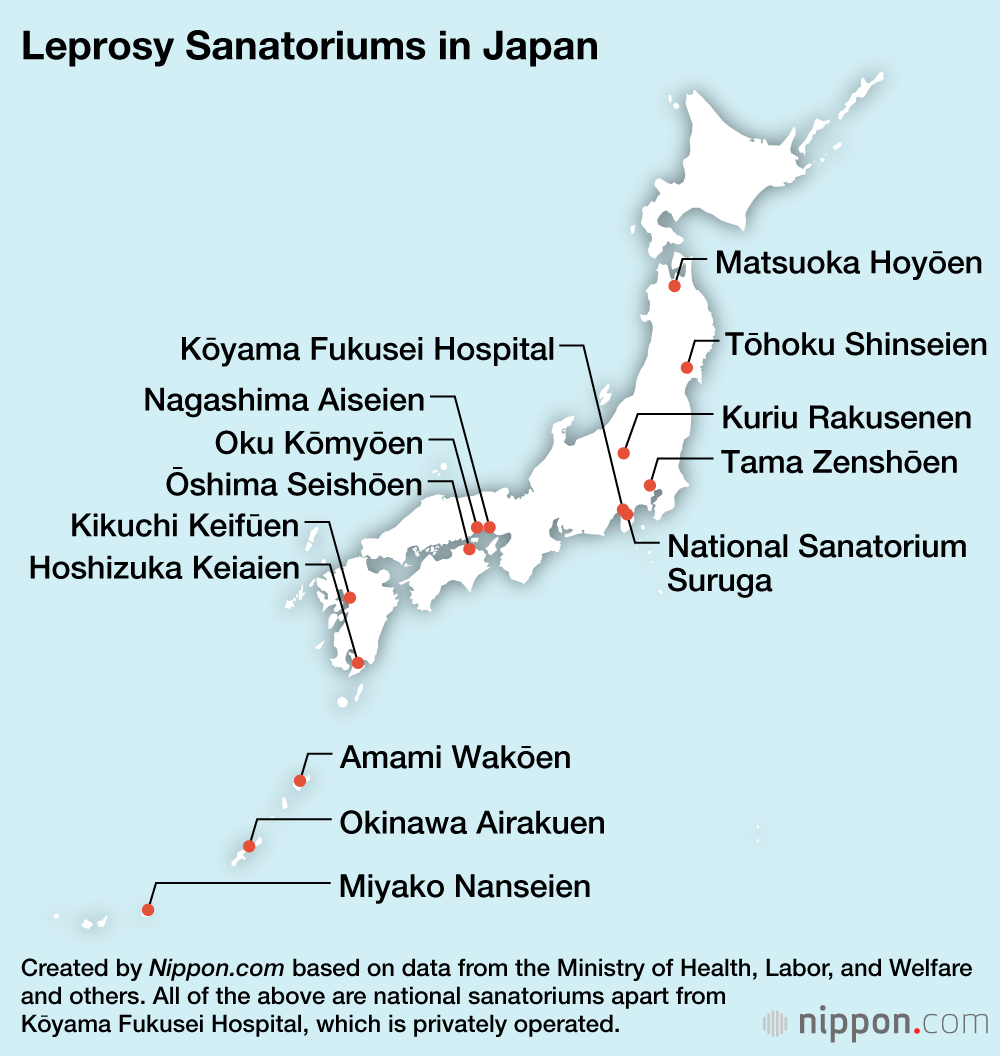

Many Hansen’s disease patients were cut off from society and their family members after being confined to a sanatorium. Even after the abolition of the isolation policy, many of the former patients have been unable to return to society, leaving them no choice but to remain in a sanatorium. According to the MHLW, there are 13 national sanatoriums and one private sanatorium in Japan, housing a total of 720 people (as of May 1, 2024).

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō (right) greets representatives of the plaintiffs in the Hansen’s-disease-related lawsuit at the prime minister’s official residence on May 23, 2001. © Jiji.)