The Japan-US Alliance Loses a Longtime Friend: Richard Armitage, 1945–2025

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Remembering the Warmth of a Friend

Richard Armitage passed away on April 13 this year. It was in the early morning on April 15, Japan time, when I heard the news. It came as a shock—just three days earlier I had been in touch with him by email, hearing that he was planning to visit Japan in May and wanted to get together. The shock was soon replaced by a blank sorrow as I thought back to the smiling face I remembered from when I first met him in Washington DC as a graduate student some three decades ago.

No matter what his mood, I remember Richard Armitage as a man of great human charm. In Japanese we speak of ki do ai raku, the “joy, anger, sadness, and pleasure” that encompass the full spectrum of human emotion. He had plenty to offer in all these areas.

In connection with ki, or joy, I recall my first visit to the United States after my inaugural election to Japan’s House of Representatives. He greeted me then with a beaming smile, wrapping me in his arms to congratulate me. I can still feel the strength of his broad, powerful chest against mine.

For do, or anger, I cannot forget the simmering rage and frustration he showed during the 1991 Gulf War, when Japan’s insistence on its noninvolvement in military affairs set it apart from the rest of the world, as its “checkbook diplomacy” opened a gulf between it and the rest of the US-led coalition at the time.

In the area of ai, or sorrow, the image that comes to mind is the visit he and I paid together to Abe Akie, widow to former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, some months after he was felled by an assassin’s bullet. The depth of the sadness evident on his face as he spoke with her brought tears to my eyes as well.

And for raku, or the pleasure we take in the company of our friends, there are countless memories for me—the times we lifted our glasses together, as he shared memories of his football-playing days at the US Naval Academy, thrilling tales of his service in Vietnam, or stories of the more than 50 foster children he helped support—many of them orphans of the Vietnam War. His witty banter, delivered in his raspy voice, brought an unending stream of stories I always loved to hear—and that often left me helpless with laughter.

Overcoming the “Bottle Cap” Thesis

Throughout his life, Richard Armitage lived in a way that presented the very model of a patriot. His intellectual stance always painted him as a dedicated friend to Japan. I would not argue with this take, but I would say that he was more accurately a friend to Japan’s alliance with the United States. He knew deep down that strong ties with the Japanese were an absolutely vital matter for American interests.

Armitage served in a number of official roles for the United States, including as deputy secretary of state under President George W. Bush in 2001–5; his area of specialization tended to be the Eastern Hemisphere, namely the region covered by the US Indo-Pacific Command. He grappled with diplomatic challenges in places like Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and the Philippines, while also working to enhance security ties among America, South Korea, and Japan.

Among his greatest achievements were the Armitage-Nye Reports, published together with Harvard Professor Joseph Nye six times in all from 2000 through 2024. These represented a monumental contribution to US policy on Japan that went beyond political lines, breathing new life into the alliance when it seemed to be drifting after the end of the Cold War and offering guidance to Democratic and Republican administrations alike, from Bill Clinton through George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden.

I was most fortunate to be able to take part in study meetings that were part of the preparations for these reports. From my time listening to those heated discussions that informed the final publications, I can say that their greatest significance may have been in their successful eradication of the “bottle cap” thesis—the theory that Japanese militarism had to be contained by the alliance with the United States, and that Japan should not be allowed to expand its security role in East Asia.

In 1990, Lieutenant General Henry Stackpole III, then head of the US Marine Corps stationed in Japan, stated: “No one wants to see a rearmed, resurgent Japan . . . you can say that we are a cap in the bottle.” US-Japanese trade friction was at its height at the time, and American theorists including former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were arguing along much the same lines. Into this debate stepped Richard Armitage with a powerful argument that Japan had to take on a greater security role. This resonated with realists concerned about a more muscular China stepping into the strategic vacuum left by the end of the Cold War, and soon the “bottle cap” concept was a thing of the past in the Asia policy discussions held in the Washington halls of power.

Last Wishes from a Friend of Japan

The first Armitage-Nye Report, issued in October 2000, stated the crux of the problem in plain language: “Japan’s prohibition against collective self-defense is a constraint on alliance cooperation.” To address the issue, it was equally clear in its prescription: “We see the special relationship between the United States and Great Britain as a model for the alliance.”

Until this report appeared, the consensus among US government officials and academics was that Washington should craft its Japan policy based on the idea that pressuring Japan to change its ways could only be counterproductive; that expanded military roles for Japan would only provoke China, and should be avoided as a result; and that therefore, Japan-US alliance cooperation should be built up with great caution.

This incremental approach was espoused by members of the group creating the report, including Joseph Nye, who had been assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs under President Clinton, and Kurt Campbell, who would later be deputy secretary of state under President Biden.

But in opposition to their views that enhanced military roles for Japan were ill-advised, Armitage consistently argued that the future rise of China made a stronger alliance with Japan a pressing need for the United States. Therefore, he stated, Washington should set about clearly communicating to Japan the roles it hoped the country would take on.

The group gradually came around to Armitage’s way of thinking. It was at this point that the “cap on the bottle” thinking that had hampered the evolution of the Japan-US alliance at last met its end.

The 2024 report, the final one in the series Armitage would put his name to, expressed deep concerns about the uncertainty of future American engagement with the international order. “The burdens of global and regional leadership will therefore fall more heavily on Tokyo in the near term,” warned the authors. As we watch the second administration of President Donald Trump drive America farther down an isolationist path today, this warning seems prescient indeed.

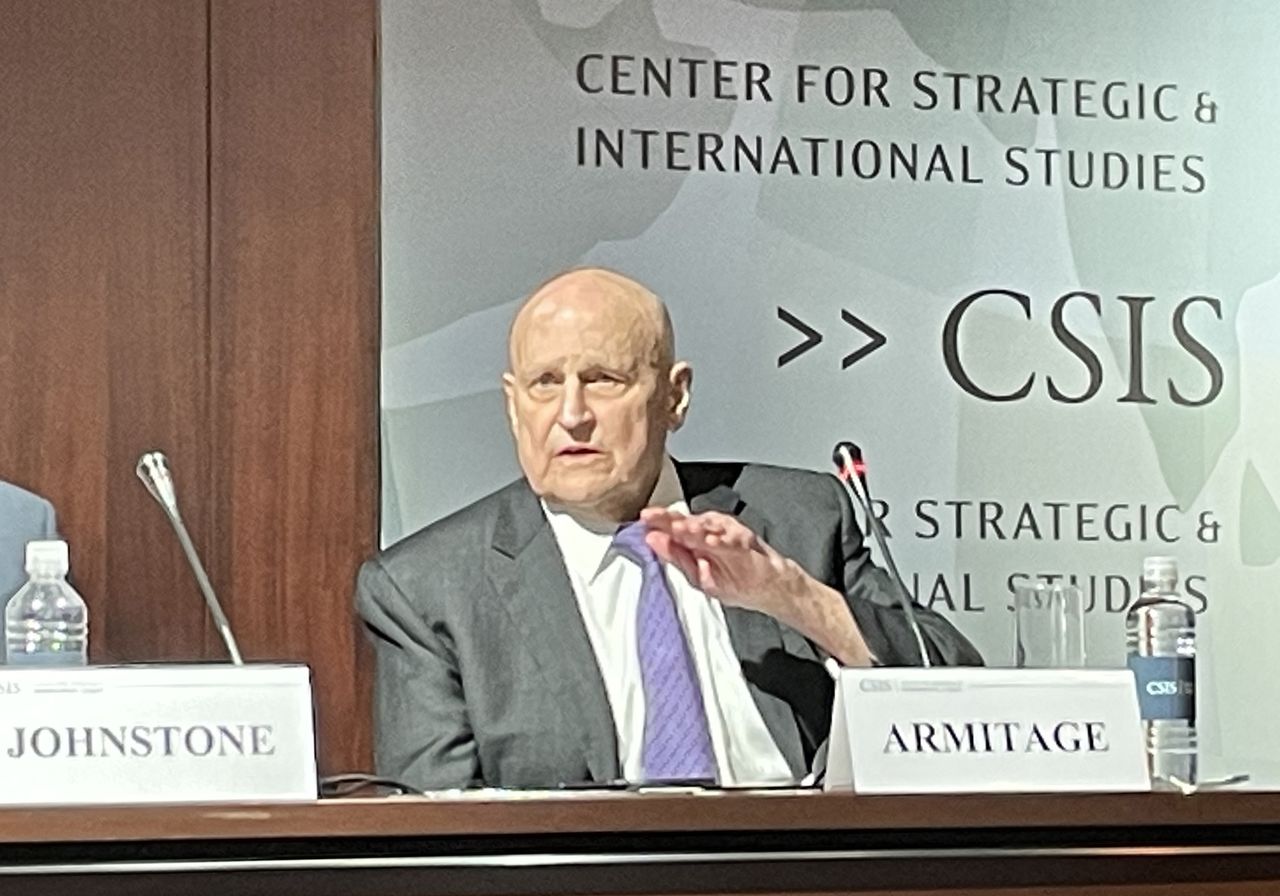

Richard Armitage explains a report offering policy proposals to Japan at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington DC, in April 2024. (© Jiji)

The time has come for Japan to extricate itself from its dependency on the United States in the area of security. Japan must be prepared to craft its own strategies and to shoulder the responsibility for regional security and a free and open international order based on rules—if necessary, taking on roles played in the past by the United States. I believe this is a duty Richard Armitage has entrusted us with as part of his last testament.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Richard Armitage in July 2015. © AFP/Jiji.)