Jack Ma Returns? “Xinomics” Struggles with Prolonged Stagnation

World Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Ongoing Deflationary Pressure

China’s economic growth for 2024 has been reported at 5.0%. However, the economic reality is not so rosy, with the urban youth unemployment rate for those aged 16 to 24 reaching 15.7% in December, surpassing last year’s figure.

Professor Luis Martinez of the University of Chicago is known for his research on estimating the GDP of countries based on nighttime luminosity from satellite images. His studies indicate that while the GDP of democratic countries closely aligns with these light-based estimates, when it comes to authoritarian countries, GDP figures tend to be significantly higher than the estimates. In China’s case, official GDP is typically about 30% higher than satellite observation suggests.

China’s supposed growth rate of 5% last year is also dubious. The country’s GDP deflator, which reflects domestic price trends, remained negative for six quarters through September 2024. Amid ongoing deflationary pressure and seriously weak domestic demand, many warn that China’s economic trajectory could become a source of instability for the world economy.

The “Rehabilitation” of Alibaba Founder Jack Ma

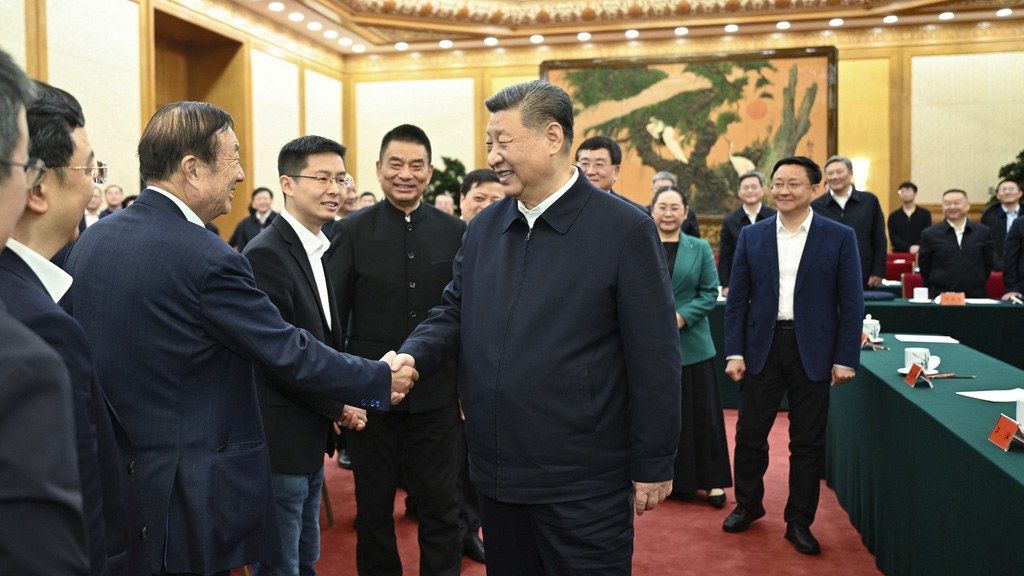

In February, the Chinese government held a symposium for the private sector, the first in six years, in which President Xi Jinping exchanged views with business leaders. Among the 14 entrepreneurs who participated was Jack Ma, founder of e-commerce giant Alibaba. He was seen shaking hands with President Xi, drawing much attention.

Back in 2020, the Chinese authorities blocked the listing of fintech firm Ant Financial, an affiliate of Alibaba, and in 2021, it was hit with a hefty fine following an antimonopoly investigation. This crackdown was believed to stem from Ma’s public criticism of China’s financial policy. He was residing in Japan for some time, almost like a fugitive. His sudden return to the spotlight seems to reflect Beijing’s desperation in its search for a solution to the economic downturn. Also present at the symposium was Ma Huateng (Pony Ma), the founder of Tencent, another major tech company that had faced fines.

China’s “reform and opening-up,” led by Deng Xiaoping (1904–97), sought to ensure that the Communist Party would thrive alongside domestic and foreign capital. But Xi, who became the country’s top leader in 2012, reversed these reforms. He called for making state-owned enterprises bigger, better, and stronger, which could be interpreted as promoting the idea of “the state advancing while the private sector retreats.” He also pushed for private companies, including foreign firms, to establish Communist Party organizations within their companies.

The growing exodus of foreign businesses from China and the relocation of their regional hubs to other countries seem to be driven by concerns over market decline and frustration with undue government interference in their operations.

That said, it would be somewhat unfair to place all the blame for China’s economic problems on Xi. A deeper look at long-term economic trends in China, as reflected in the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database, will provide more context.

Under the administration of Hu Jintao (2002 to 2012), which prioritized maintaining a GDP growth rate of 8% or higher, growth remained around 10% per annum. However, in 2012, the final year of Hu’s administration, growth dipped below 8% for the first time, landing at 7.8%. The Hu government, which had been aggressively stimulating the economy, launched a 4 trillion yuan economic package in response to the 2008 financial crisis centered in the United States, possibly fueling a bubble. By the time President Xi declared that “houses are for living in, not for speculation,” the bubble was already in the process of bursting.

Economic growth under the Xi administration began in the 7% range but declined year by year. The Chinese economy experienced a sharp slowdown during the 2020 pandemic, ultimately leading to where it is today.

A notable feature of China’s economy is its exceptionally high savings rate, at 40%–50% of GDP, along with its total investment rate (public and private combined), which exceeds 40% of GDP. However, its private consumption expenditure, which in most countries accounts for more than half of GDP, is low, at around 40%.

The latest figures show that China’s total investment accounts for 41% of GDP, compared to 26% in Japan, 21% in the United States, and 33% in India. The gross savings rate is 43% in China, versus 30% in Japan, 17% in the United States, and 32% in India. China clearly stands out in both investment and savings.

Investment After Investment: The Fallout

In economies where investment is limited and savings are excessive, stagnation will result unless savings are turned toward investment. However, following up investment with more investment will result in diminishing returns.

An example of this can be seen in China’s high-speed rail network. Rapidly expanding after its launch in 2008, it now stretches over 40,000 kilometers, equivalent to the Earth’s circumference. Yet, only the Beijing-Shanghai route is profitable, and China Railway is burdened with a debt equivalent to some ¥120 trillion.

Likewise, the nation’s expressway network has grown to a total length of about 180,000 kilometers, which is enough to circle the Earth over four times. In designated development zones, unfinished skyscrapers stand abandoned, falling into decay. Meanwhile, of the world’s annual cement consumption of about 4 billion tons, China has been using more than 2 billion tons.

China’s relentless cycle of investment has led to a slowing economy. It was once seen as only a matter of time before the Chinese economy surpassed the United States. Now, an increasing number of people are thinking that day may never come.

Massive Bad Debt and Population Decline

China’s share of global nominal GDP (measured in US dollars) peaked at 18.3% in 2021, after which it fell to 16.9% in 2023. It is highly likely that the Chinese economy has already reached its peak in terms of global share.

The Chinese authorities have, albeit belatedly, issued special long-term bonds in an effort to reboot the economy. Beijing plans to subsidize the purchase of home appliances, smartphones, tablets, and other goods, but there is a risk this could lead to a front-loading of consumption. An alternative approach could have been to massively increase social security spending, which would reduce the need for precautionary savings and encourage more consumer spending.

The authorities also appear to have begun injecting capital into state-owned banks burdened with bad debt. The amount of bad debt that the Japanese government managed in the wake of the asset bubble collapse was roughly ¥100 trillion. Given the scale of China’s economy, its bad debt may be several times—or even 10 times—higher.

The country’s most pressing concern is demographics. When Japan’s bubble burst, its population was still growing. China’s population has been declining for three years since 2022. In 2024, it fell by 1.39 million, and in 2025, the total is expected to drop below 1.4 billion.

China’s total fertility rate—the average number of children that are born to women over their lifetime—is around 1.0, less than half the replacement level of 2.1. It is no easy task to revive economic growth when the demographics are approaching a reverse pyramid structure. There is a heightened risk of the population “aging before fully achieving prosperity.”

In a New York Times column in July 2023, Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Krugman wrote that people ask him if China’s future might resemble what happened in Japan. “My answer is that it probably won’t—that China will do worse.” It seems his prediction may come true.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping engaging with private sector leaders. Beijing, on February 17, 2025. © Xinhua/Kyōdō.)