Growing Closer in Tough Times: A Look at Japanese Understanding of Ukraine

World Politics Global Exchange- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Russian Propaganda

In September 2006, I arrived in Japan for a one-semester Japanese language program. It was my first time ever traveling abroad. It was also the first time I learned that most Japanese people know very little about my home country, Ukraine.

When I would introduce myself as a Ukrainian, there were many Japanese people that would, without hesitation, ask me about Russia’s climate, culture, and literature, despite the fact that I had never even been to Russia. More surprising was that, in Japan, Ukrainian history and art were either mistakenly attributed to Russia or completely unknown. As I found myself repeatedly explaining to people that Ukraine is not Russia, I wondered how these flawed views came to be in the first place.

Ukraine, as a post-Soviet state, has often been viewed in Japan as a country entirely within Russia’s sphere of influence. One reason for this is that Japan has largely learned about Ukraine through information disseminated by Imperial Russia, the Soviet Union, and later the Russian Federation. Seen a different way, Russia, as a typical colonial power, has historically suppressed Ukraine’s voice while positioning itself as the sole spokesperson for the country. Russian narratives then made their way into publications and became widely reflected in media.

In 2014, I was again confronted with the reality of how dangerous Russia’s distorted history and propaganda about Ukraine can be. That February, Russia occupied Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, and later seized part of the Donbas region in the east of our country. While the Japanese government criticized Russia and imposed economic sanctions, the Japanese media at the time failed to sufficiently analyze information coming from Ukraine and instead unquestioningly accepted the information coming from Russia. Russian fake narratives—such as that Crimea is historically Russian, that Ukrainians and Russians are “family nations,” and that Russian speakers in Ukraine are Russian—were often broadcast without scrutiny. Over time, such media reports dwindled, and Japanese people began to forget about the prolonged war between Ukraine and Russia.

Becoming a More Familiar Country

Then, on February 24, 2022, Russia launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The Japanese government immediately expressed its support for Ukraine, and explicitly condemned Russia for attempting to unilaterally alter the status quo through force. I still clearly recall how powerfully symbolic Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s words were in showing support for Ukraine in February 2023 when he said, “Today’s Ukraine may be tomorrow’s East Asia.”

The Japanese media’s reporting was significantly different this time, perhaps because of their lessons learned in the years since 2014. They brought attention to Russia’s war crimes and Ukraine’s humanitarian crisis with real-time reporting from the ground, and even featured insights from a few Japanese scholars specializing in Ukraine.

At the time, I was receiving an unprecedented number of translation requests from various Japanese media companies, as were other Ukrainian translators. For the first six months, I was deeply involved in television news and program production almost daily. These programs covered not only the situation in Ukraine but also historical and cultural interpretations, the harsh measures Russia had imposed on Ukraine (such as the history of the prohibition of the Ukrainian language) and a wide range of other topics. The contrast with the coverage a decade earlier was striking.

A sign thanking Japan for its support of Ukraine in Shinjuku, Tokyo, on November 17, 2024. (© Yuliana Romaniv)

One of the most symbolic changes was the decision by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to switch from using the Russian name Kiev (transcribed as キエフ in Japanese) for Ukraine’s capital to the Ukrainian Kyiv (キーウ). Must of Japan’s media followed suit, with other geographical names also updated from Russian to Ukrainian: Odessa (オデッサ) became Odesa (オデーサ), Chernobyl (チェルノブイリ) became Chornobyl (チョルノービリ), and the river Dnieper River, Dnepr in Russian (ドニエプル川), was changed to Dnipro (ドニプロ川).

As a Ukrainian, I was genuinely happy to witness this shift, and in that moment I truly felt that Japan’s view of Ukraine had transformed. For many Japanese people, Ukraine went from a country they knew little about to one that they were familiar with.

Growing Public and Academic Interest

I have lived in Japan since 2012 and currently teach at a university. As was the case in many other countries, Ukrainian studies were almost nonexistent in Japanese academia. Even in educational institutions specializing in Eastern and Central European studies, matters on Ukraine were largely viewed through a Russian lens, and were not considered from a global perspective. As evidence of this, among the approximately 800 universities in Japan, there were only a handful of universities that had introduced the Ukrainian language as a subject prior to 2022.

To truly become an expert on a country, one must first learn to read and write in its language. Without this, understanding its history and social realities is difficult. On the flip side of this, spreading Ukraine’s history and language will foster a more accurate perception of the country; even more, it will strengthen international cooperation in resisting Russia’s ambitions to reshape the global order. Over time, I’ve become increasingly convinced of this.

I started asking myself what I could do. How could I sustain and increase people’s interest in Ukraine? The answer began to take shape through an open lecture I started giving at the university where I’m employed, called “History and Culture of Ukraine.” I’ve given this lecture annually since 2022, and each time, dozens of participants attend. Seeing their serious engagement, I finally feel that a time has come where Ukrainians are able tell their own story.

The author presents a lecture on Ukrainian history and culture at Ibaraki Christian University in October 2023. (Courtesy of Yuliya Dzyabko)

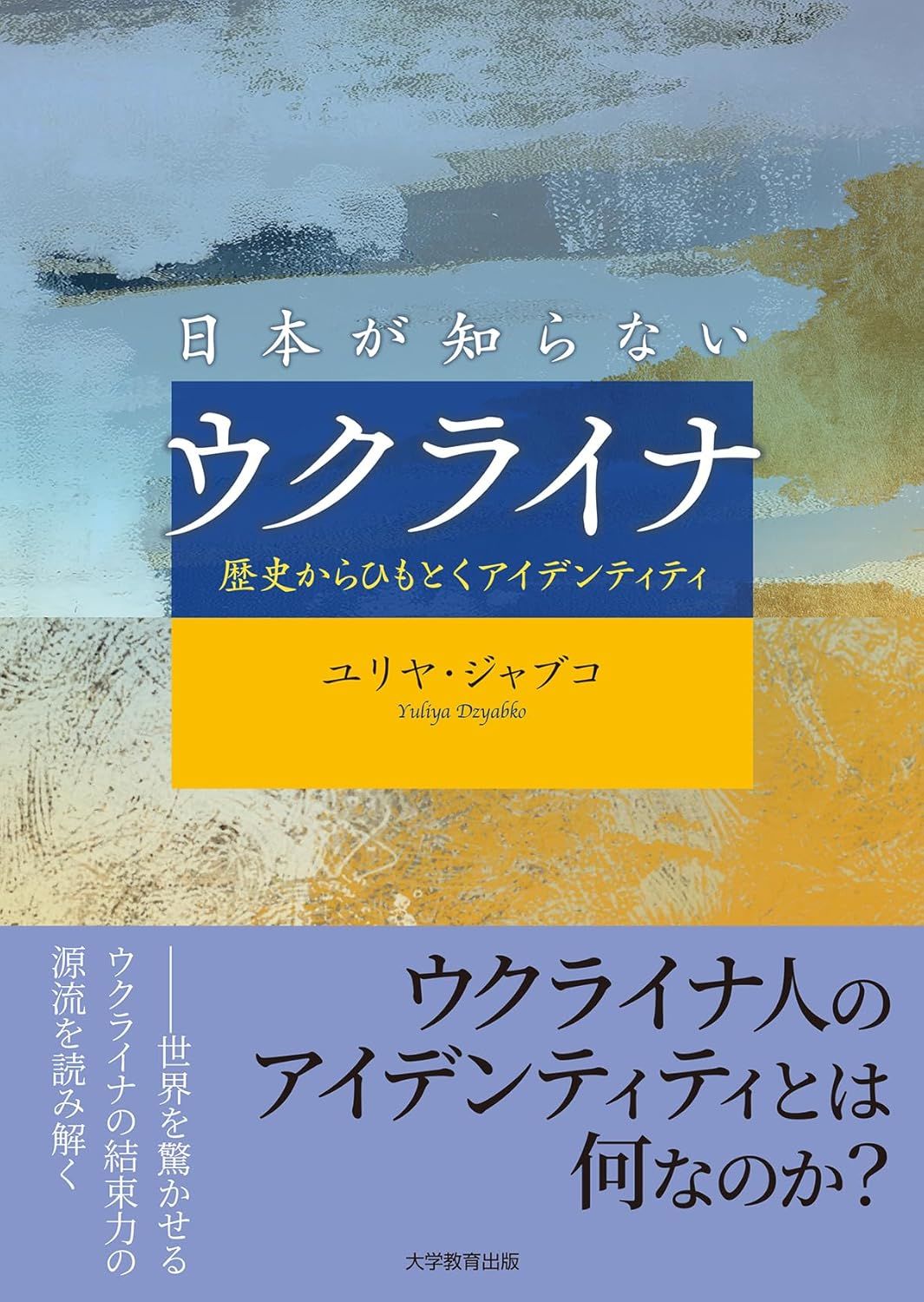

The author’s Nihon ga shiranai Ukuraina (Ukraine Unknown to Japan) is now in Japanese readers’ hands. (Courtesy of Yuliya Dzyabko)

I once asked a 70-year old woman who attended why she was interested in the course. She told me, “I started helping the people of Ukraine, but I didn’t know much about their land. If I’m going to support a country, I ought to understand it.” Her simple words moved me deeply and reassured me that steady progress was being made.

Another promising development is the increasing number of publications on Ukraine. Beyond politics, history, and military affairs, there are now literary works, firsthand war diaries, and numerous other translations across various genres. This trend is greatly contributing to a real understanding of Ukrainian identity.

Expanding Grassroots Solidarity

Over the past three years, interactions between Ukrainian and Japanese people have steadily deepened. Currently, there are about 4,000 Ukrainians living in Japan, with half having evacuated with the support of the Japanese government. These Ukrainians are participating in international exchange events held across Japan and organizing exhibits and gatherings to support Ukraine, with the help of NPOs and other groups.

One notable example is Stand with Ukraine Japan (SWU Japan), a group founded mainly by Ukrainians living here. They gather twice a month in Tokyo with the support of Japanese allies. Participants gather to hold peace demonstrations, carrying antiwar placards and Ukrainian flags.

A woman carries a Ukrainian flag in support of the country at a well-attended November 2024 event in Shinjuku, Tokyo. (© Yuliana Romaniv)

Another important group is the NPO Kraiany, a Ukrainian community in Japan, which has the longest history among groups promoting exchange between Japanese and Ukrainian people. In May last year, the Ukrainian Cafe Kraiany in Mitaka, Tokyo, hosted an event which I attended and that drew many Japanese visitors. One participant, a man in his sixties, said: “Ukrainians teach me about their history and culture. In this way, our interaction is deepening.” Such dedicated efforts are undoubtedly bearing fruit.

The Japanese perception of Ukraine is gradually evolving to one of a nation fighting for its freedom and independence. The process of knowing and understanding a country takes time, but we must remember that relations between countries always begins from personal connections. As I conclude, I would like to express my sincere gratitude as a Ukrainian to the people of Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Members of the group Stand with Ukraine Japan attend an event to support the country in Shinjuku, Tokyo, on November 17, 2024. © Yuliana Romaniv.)