Buried Timebombs: Saitama Sinkhole Draws Attention to Japan’s Aging Wastewater Infrastructure

Society Disaster- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Calamity Waiting to Happen

The scene in Yashio, Saitama, on January 28 was straight from a disaster film: A giant hole appeared without warning in a busy intersection, swallowing pavement, utility poles, and a passing delivery truck whole. The accident sent city and prefectural officials scrambling to assess the damage and draw up a response. Meanwhile, news cameras followed first responders as they struggled in vain to reach the trapped driver of the truck. Conditions at the site worsened in the following days as the sinkhole grew to 40 meters in diameter, shifting efforts to extract the driver from a rescue to a recovery operation.

The gaping sinkhole at the intersection in Yashio, Saitama, as seen on February 4, 2025. (© Jiji)

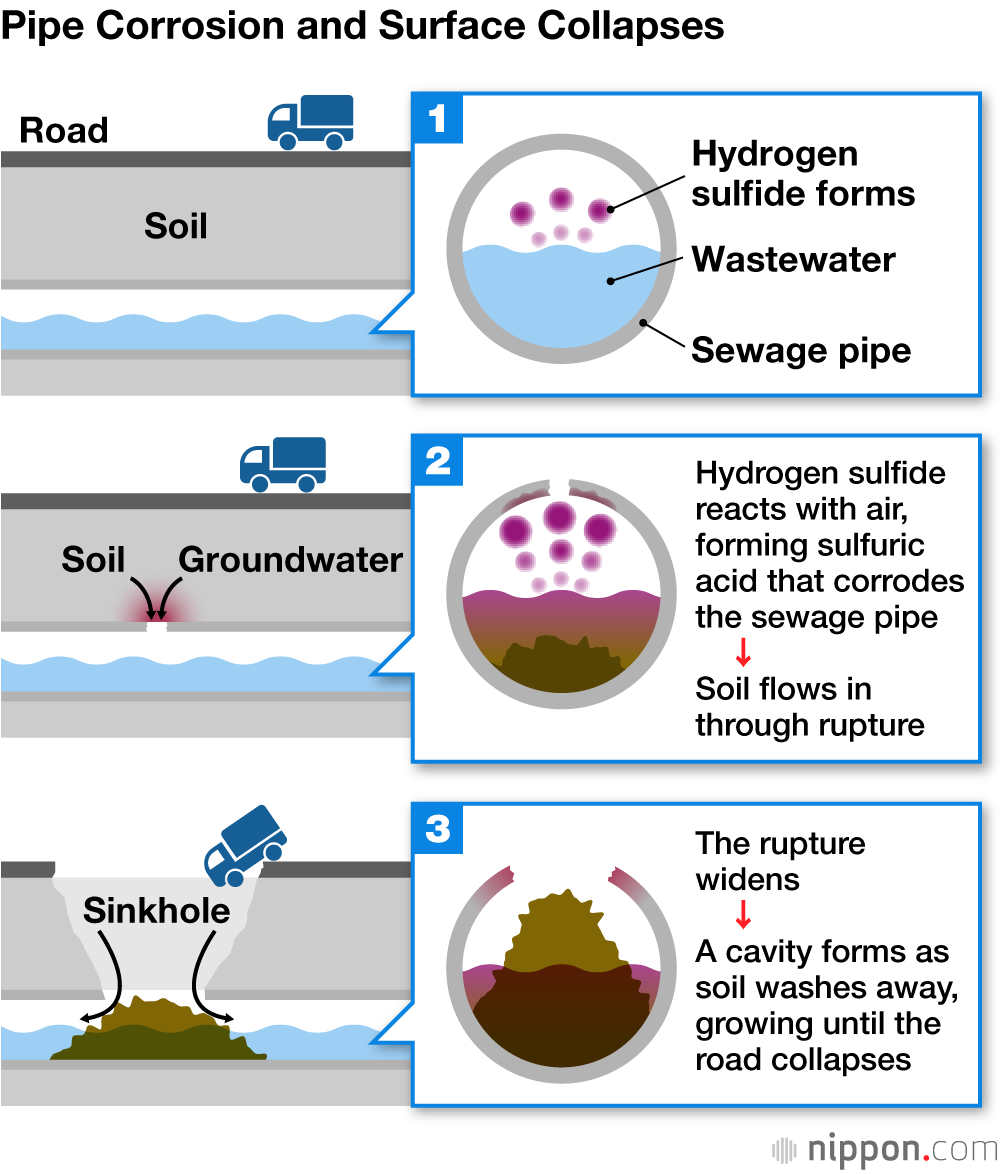

The sinkhole was caused by a massive rupture in a sewer pipe running deep below the prefectural road. Installed in 1983, the 4.74-meter-wide reinforced concrete pipeline had corroded at a bend, slowly eaten away by sulfuric acid until it finally collapsed.

The environment inside sewage pipes is ideal to the formation of the caustic compound, which is created when hydrogen sulfide built up from the anaerobic breakdown of organic material mixes with oxygen. Hydrogen sulfide tends to concentrate at curves and other areas where the rate of flow is disrupted, corroding the concrete and metal of pipes.

Compounding the scale of the damage in Yashio was the poor soil condition under the intersection. An investigation found the soil to be a loose mixture of silt and clay, which readily poured through the hole in the pipe, carving out a cavity beneath the road as the rupture grew. Experts investigating the site noted that using a firmer backfill when installing the pipeline would have reduced or even prevented the cave-in.

Workers at the site of the initial collapse on January 28, 2025. The sinkhole initially measured 10 meters in diameter but soon grew to 40 meters. (© Jiji)

The impact of the collapse extended far beyond the immediate disruption to traffic and businesses in the area, affecting wastewater services for 1.2 million residents in the prefecture. Authorities called on inhabitants of surrounding cities to reduce their water usage, pressing them to curtail activities like bathing and washing clothing. In addition, wastewater was collected to reduce the flow to the damaged pipe, with the effluent then chlorinated and released into a nearby river, potentially damaging the environment.

The wide scale of service disruption is linked to Japan’s approach to wastewater management. Wastewater operations are overseen by public sewage systems operated by a single municipality or regional sewage systems operated jointly by multiple municipalities. The pipeline in Yashio was in the latter category and carried wastewater collected from 12 municipalities. While such regional management systems provide significant advantages to cities in terms of efficiency and cost savings, the failed pipe and resulting sinkhole illustrates the risk of widespread disruption of services when anything goes wrong.

Moreover, the incident laid bare the fragile state of Japan’s sewage infrastructure. Morita Hiroaki, who heads the prefectural panel studying the gargantuan task of repairing the damaged pipe, highlighted the direness of the situation when he warned that reconstruction could take at least two or three years to complete.

Sewerage systems are a backbone of modern societies, serving to preserve sanitary conditions in communities, protect the natural environment, and prevent flooding. The loss of services has serious repercussions on public health and welfare. Morita’s stark assessment has shaken public confidence and leaves residents wondering when a catastrophe like another sinkhole or a natural disaster will arise to knock the wastewater system offline for a longer term.

Rainy Season Concerns for Aging Networks

The sinkhole also damaged the stormwater system, raising the risk of flooding when spring and summer rains arrive. Japan has seen an uptick in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather like torrential downpours and typhoons due to climate change. When the skies open, municipal storm drains can easily be overwhelmed, flooding city streets and neighborhoods. Low-lying areas are particularly vulnerable, and it falls to authorities to maintain the resilience of infrastructure by regularly inspecting systems and carrying out climate risk assessments, which enable local governments to effectively invest in the upkeep and upgrading of systems.

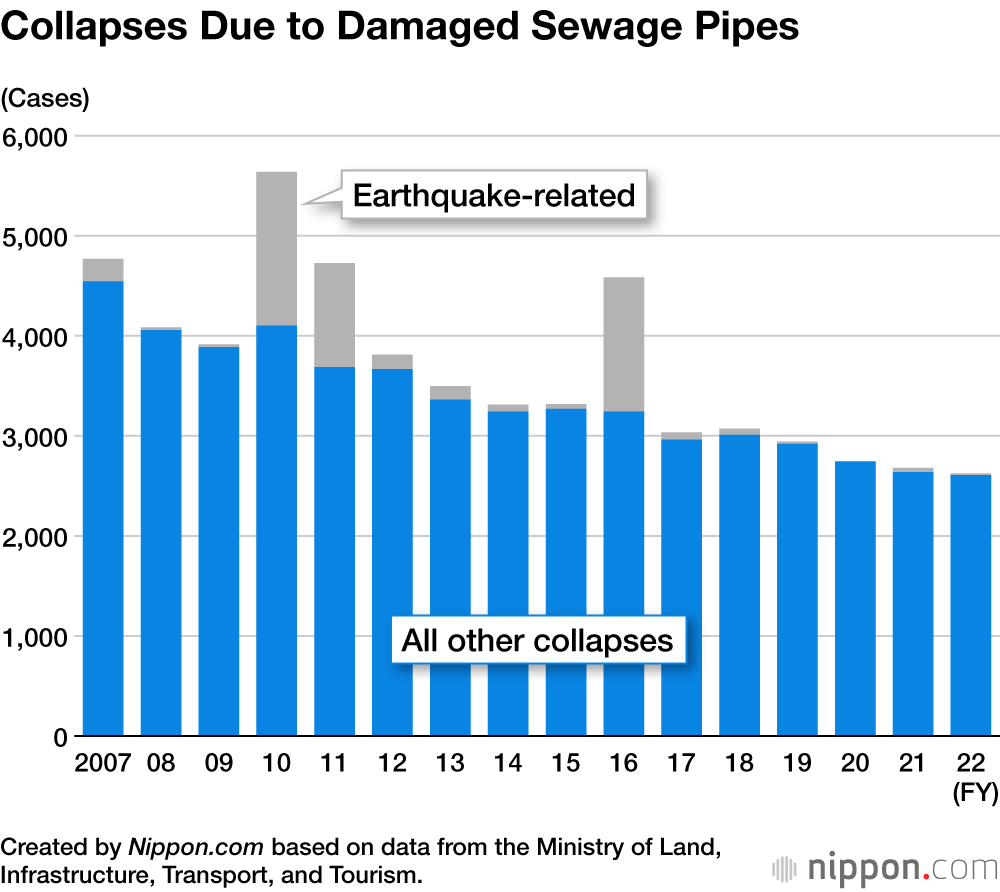

It would be a mistake to see the sinkhole in Yashio as an isolated incident. Indeed, the same factors that led to this collapse threaten sewerage systems throughout the country. In 2015, revisions to Japan’s Sewerage Act mandated that local governments increase inspections of sewer lines at spots susceptible to damage from aging and corrosion, and to carry out repairs as needed. Collapses have subsequently decreased, falling to around 2,600 in 2022. While the vast majority of sinkholes are less than a meter deep, the scale of disruption posed by larger cave-ins such as in Yashio that account for 2% of incidents cannot be underestimated.

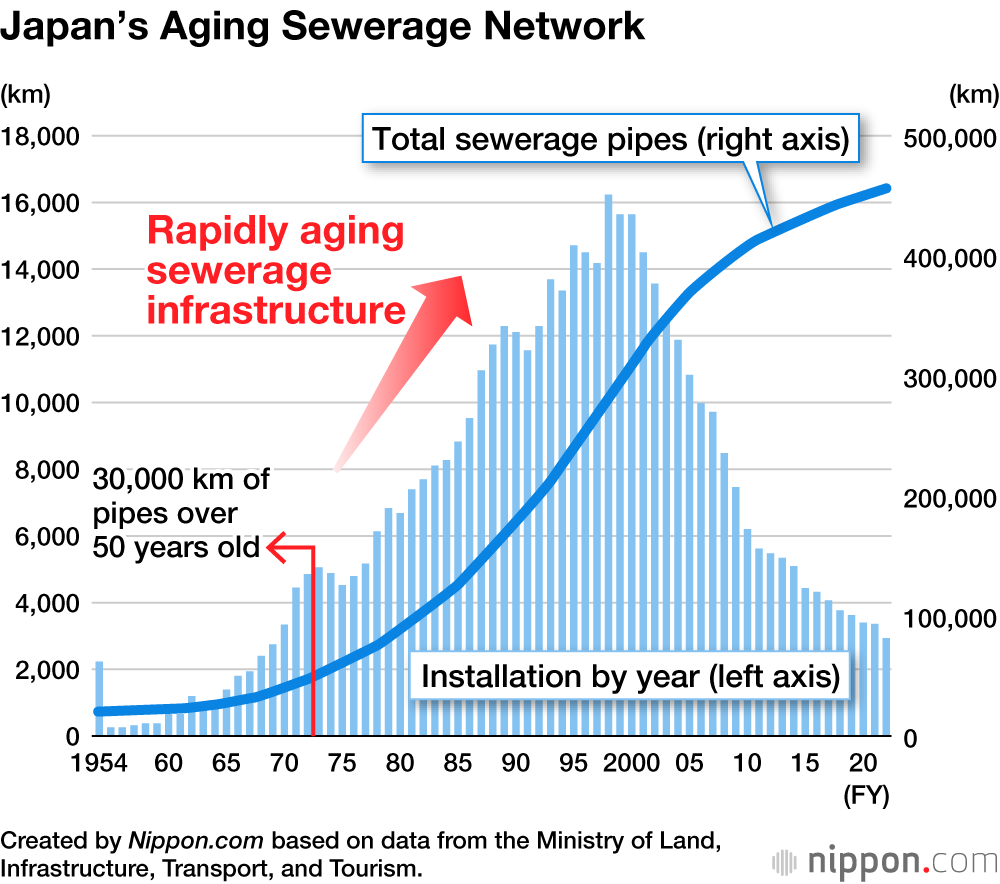

According to MLIT, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, Japan has some 490,000 kilometers of sewage pipes nationwide as of the end of fiscal 2022 (March 2023). Much of the network was installed during the country’s rapid economic growth extending from the 1950s to the 1970s, a period that saw a rapid rise in the standard of living in Japan. Currently, the ratio of pipelines that are over 50 years old stands at 7%, but this is set to increase to 19% in 10 years and will reach 40% in 20 years.

This state of affairs has been highlighted by a number of recent cases similar to Yashio of large sinkholes caused by ruptured sewer pipes. In June 2022, a cave-in on a major highway in the town of Kawajima in Saitama left a hole in the road 1.5 meters across and 3 meters deep, into which fell an 80-year-old man on a bicycle. In July the same year, a 60-centimeter hole in a sewer pipe laid in 1982 caused a road in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture, to collapse, leaving a crater that measured 4.5 meters long, 11.6 meters wide, and 2 meters deep.

In an incident unrelated to sewerage infrastructure, a collapse near Hakata Station in Fukuoka in November 2016 drew international attention for the speed of recovery work, with an army of cement truck and workers filling the 15-meter-deep chasm in a week. The speed of the recovery, in contrast to the plodding effort in Yashio, owes to the fact that the collapse occurred at 5:00 am when the streets were empty, as well as readily available construction crews. If the accident had occurred a few hours later, when people were on their way to school or work, there would almost certainly have been one or more victims, which would have severely hampered the speed of the repair work.

Understaffed and Underfunded

Although faced with a mounting need to inspect and upgrade aging sewerage infrastructure, municipalities are falling further and further behind in their upkeep. A major factor is labor shortages. The number of workers at wastewater treatment facilities throughout Japan has steadily declined as the expansion of sewerage infrastructure has leveled off and cities streamlined services. In 1997, there were 47,000 workers in the industry, but by 2021 this figure had fallen to 26,900. Subsequently, the frequency of inspections and monitoring has dropped off, with crews managing to check pipes once every five years at the most. MLIT has encouraged cities to outsource some of the work to private companies, but the policy has done little to alleviate the situation as contractors are grappling with the same shortage of qualified technicians as municipalities.

Saitama governor Ōno Motohiro (center) heads a meeting of a panel studying the cause of the sinkhole in Yashio in the prefectural capital Saitama on January 31, 2025. (© Jiji)

Climbing costs are also adding to the burden of operating wastewater treatment systems. Revenue from sewage services has been on a steady downward slide as the Japanese population declines and the public has increasingly adopted water-saving measures. When the time comes to replace aging infrastructure, cities all too often lack the money for projects.

Local governments are required to fund wastewater treatment services through user fees, but many are in fact reliant on central government subsidies to finance systems. Even those that are in the black receive some 28% of their income and 17% of the money for capital expenditures from subsidies and other outside sources. The application process for receiving these funds is laborious and time consuming, and payments are often delayed, placing municipal wastewater management on unstable financial footing.

What is more, sewerage systems are more expensive to operate and maintain than public water service. They utilize larger pipes that are buried deeper underground, with the costs of replacing or fixing sections running three to four times higher than for waterworks. Pumps are also needed to keep the effluent moving through the network, further raising overhead costs. Usage fees are typically too low to cover operating expenses, and unless these are brought in line with operating costs, municipal governments will continue to struggle to adequately maintain systems, potentially impacting the level of public services and the quality of life of citizens.

Tackling the Problem with New Technologies

There are bright spots, however. Japan is working hard to bolster its arsenal of monitoring tools by focusing on stepping up the frequency and efficiency of inspections. Examples of this are the use of special camera systems to scan the interior of manholes and utilization of robots to inspect the inside of pipes, enabling crews to quickly and easily survey conditions from the surface.

There are also efforts to increase the adoption of advanced technologies, such as sensors, drones, and machine learning to detect deteriorating or damaged stretches of pipe. Taking advantage of these tools to regularly monitor conditions inside sewer pipes enables operators of wastewater systems to easily and accurately identify vulnerable areas. Using AI, for instance, workers can analyze past data to pinpoint locations prone to corrosion and take steps before they become an issue.

There are also efforts to introduce new and better techniques to rehabilitate old, worn pipes to extend their lifespan, which is less time-consuming and more cost-effective than replacement. These include cured-in-place-pipe lining, a method of inflating and hardening a specially treated tube inside an existing conduit to restore it to near-new conditions, and spiral relining that involves inserting a continuous, rigid polyvinyl chloride strip that is wound into a spiral shape to form a new pipe inside the old one. These methods do not involve digging or excavating, although they are somewhat limited in their use as they cannot be applied to pipelines that are severely deteriorated, and their lifespan is only around 10 years.

Sewage pipeline construction. (© Pixta)

Partnering for the Future

Even with the development of new technologies, the national government needs to take the lead on protecting Japan’s aging wastewater infrastructure rather than leaving it solely to municipalities. Toward this end, on February 5, the government brought together experts to formulate a new plan for strengthening the national land infrastructure, during which it indicated that repairing and rebuilding the nation’s water and sewer pipelines would be a priority.

Local governments have called for greater access to and flexibility of subsidies, while voicing concerns that even with financial support, labor shortages hamper their ability to build new pipelines and repair existing ones. This latter point lacks a quick and easy solution, making it unlikely that the current pace of projects will increase in the foreseeable future.

It is crucial that the national and local governments work together to shore up the finances of sewage treatment systems and promote the training of new wastewater technicians and other specialized personnel. The people, too, have a role to play, and efforts must also be made to raise public awareness and understanding of the importance of sewerage infrastructure.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: An overhead view of workers in Yashio, Saitama, as they attempt to reach the truck driver trapped in the sinkhole. Photo taken on February 6, 2025. © Kyōdō.)