What Makes the Brazil-China Partnership Tick? Lula’s Multilateral Diplomacy in Context

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Leader of the Global South

Brazil has traditionally stressed an independent foreign policy, actively engaging in multilateral diplomacy and rejecting subordination to any major power. For many years, simply resisting US influence in Latin America was the top diplomatic priority. In the early years of this century, however, the focus began to shift in response to the decline in US clout and the rise of the emerging economies. Under the first administration of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, or “Lula” (2003–11), of the left-leaning Workers’ Party, Brazil began to pursue a more aggressive and wide-ranging foreign policy, positioning itself as a leader of the Global South through such forums as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the Group of 20.

That trend was interrupted when a disillusioned public voted out the scandal-plagued Workers’ Party and subsequently installed the far-right administration of Jair Bolsonaro (2019–22). But Lula returned to power in 2023, and he has tackled his job with vigor and zeal, age and health concerns notwithstanding.

Although eager to cooperate with the industrially advanced world on global issues, President Lula’s administration is nonetheless seeking sweeping reforms in an international order that many believe unfairly benefits the Western countries that designed it. In this connection, his government has shown a pronounced tendency to align itself with China in such multilateral forums as the BRICS and G20, even while maintaining Brazil’s longstanding emphasis on relations with other Latin American countries. In the following, we will take a closer look at recent developments in “Lula diplomacy” and consider their implications for Brazil and Japan.

Brazil, the BRICS, and Argentina

The emerging powers that make up the BRICS have been engaged in an ongoing struggle for leadership of the group, driven by diverging values and interests. The recent addition of Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates to yield the nine-member BRICS+ has only added to the group’s ideological and economic diversity, making it more difficult than ever to pursue a coherent agenda.

Originally, Argentina was among the countries seeking to join the framework. Like Brazil, Argentina is a full member of the Southern Common Market, or Mercosur (along with Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay), and Brazil supported its bid to join the BRICS, eager to enlist a powerful, like-minded ally.

The Workers’ Party regime headed by Lula and his successor, Dilma Rousseff, coincided closely with the Argentine administrations of Nestor Kirchner and Cristina de Kirchner (2003–15) of the leftist Peronist Party (formally, the Justicialist Party). At that time there was a strong ideological affinity between the Brazilian and Argentine governments, co-leaders of the “pink tide” in Latin American politics. Both were critical of the global trend toward neoliberalism. In addition, the two countries shared an ideological climate that nurtured the growth of dependency theory, which calls for a shift away from the capitalist system that sustains the wealth and power of the industrial West.

The Peronist Party’s Alberto Fernandez (2019–23) took over in Argentina during the period when the Workers’ Party was out of power in Brazil. The Fernandez administration lobbied for Argentine membership in the BRICS while cultivating closer ties with Beijing. But the Peronist regime fell victim to Argentina’s chronic financial instability, the result of government overspending and crippling debt. With another default looming and inflation soaring to almost 200%, the nation voted the rightist Javier Milei into power in 2023. Steering a pro-American, anti-Chinese course on foreign policy, Milei passed on membership in the BRICS+, even though Argentina’s bid had already been approved.

Today, there are few Latin American countries other than Brazil willing and able to pursue a robust Global South diplomacy. Mexico was a leading force in the developing world during the Cold War, but since then its economy has become closely intertwined with that of the United States. As a result, the relationship with Washington remains central to Mexico’s foreign policy regardless of the party in power. Under socialist President Hugo Chavez (1999–2013), Venezuela was a major torchbearer for anti-American leftism in the region. But when Chavez’s successor, Nicolas Maduro (2013–present), took over, political order deteriorated, and the country mutated into a dictatorship notorious for its brutal suppression of human rights, and like Nicaragua, it is now shunned by much of the region and the international community. Under the regime of President Fidel Castro, historically leftist Cuba enjoyed a position of high prestige in Latin America, but today it is struggling just to survive.

Roots and Fruits of the Brazil-China Partnership

Under the circumstances, Brazil has been compelled to look outside the region for a strong ally in its bid to reform global governance. Russia has had its hands full maintaining its own standing since it invaded Ukraine. The current Indian government cares only about what directly benefits India. And South Africa has no real desire to exercise leadership. This leaves economic superpower China as far and away the most promising partner. Beijing, for its part, has long regarded Brazil as its top diplomatic priority in Latin America.

Trade between Brazil and China has expanded rapidly since the beginning of this century, and China is now Brazil’s largest trading partner. Brazil exports a number of commodities that China needs, including soybeans, iron ore, and oil, and China provides Brazil with machinery, electric vehicles, solar panels, electronic devices, telecommunications equipment, and more. China imports mineral resources and agricultural goods from Argentina, Chile, and Peru as well, but by volume, Brazil dwarfs China’s other Latin American trading partners. Although China still ranks well below a number of Western countries as a source of foreign direct investment in Brazil, its investments have grown substantially since 2010. The focus of this FDI has been oil extraction and agribusiness, but Brazil has also welcomed Chinese investment in infrastructure projects, such as power distribution systems.

For many years now, Brazil and China have been cultivating a cooperative relationship based on mutual recognition of one another’s regional leadership positions in the developing world. Brazil instituted diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1974 and entered into economic cooperation with China after the latter began pursuing economic growth and technological development under the policy of “reform and opening up.” This cooperation extended even to high-tech areas, as seen in the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite joint research and production program, established in 1988. In 1993, Brazil became the first country in the world to sign a strategic partnership with China. When China was lobbying for membership in the World Trade Organization, Brazil was the first state to recognize China as a market economy.

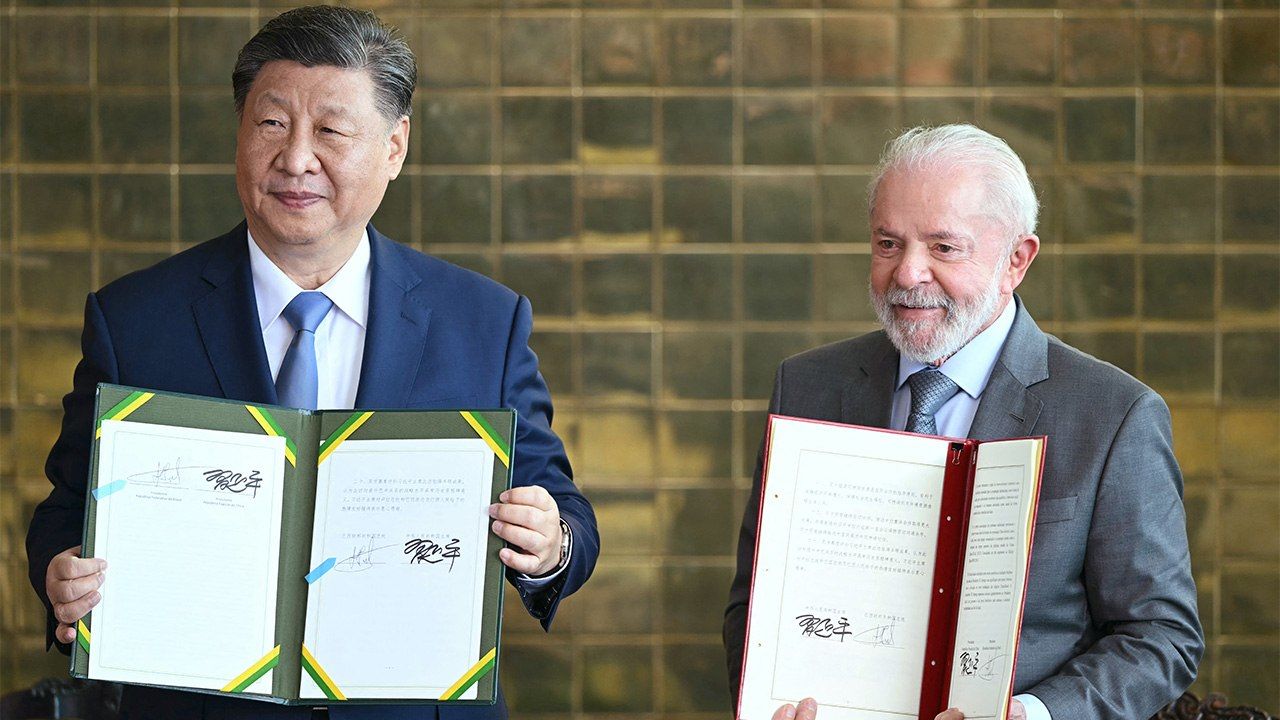

At the November 2024 bilateral summit that followed the G20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro, President Lula and President Xi Jinping celebrated 50 years of diplomatic ties with a statement elevating their “global strategic partnership” to the level of a “community.”

Brazil and China have concluded so many agreements in a wide range of fields that a great deal of redundancy has resulted, leading some to stress the need for consolidation. Beijing has been eager to enlist Latin America’s largest country in its Belt and Road Initiative as a matter of prestige, but there is no real necessity, from the standpoint of relationship building, for Brazil to sign on, and Brasilia is wary of any commitment that might compromise its autonomy, a core principle of its foreign policy. At the November 2024 bilateral summit, Lula and Xi ultimately agreed to “synergize” the Belt and Road Initiative and Brazil’s development strategies.

A New Form of Neocolonialism?

The Chinese government is in the habit of promoting sweeping initiatives and sketching in the details only after partners are already onboard. This style of diplomacy and deal making is at odds with Japan’s fastidious, cautious approach, but it seems to go down well in many Latin American countries, including Brazil. The words “belt and road” in particular have an almost magical power to raise expectations in the region. President Xi issued his invitation to Latin America to participate in the BRI in 2017, and with the exception of Brazil (already involved in similar arrangements), the region’s governments announced their assent in rapid succession.

The US government and analysts around the world have sounded the alarm about China’s “debt-trap diplomacy,” but for the most part their warnings have fallen on deaf ears. The Port of Chancay in Peru, built with financial assistance from China, was inaugurated on November 14, 2024, to coincide with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Lima, just prior to the G20 summit in Rio. The port is attracting considerable excitement as a major new distribution hub linking Asia and South America.

There are concerns, however, that what some portray as a blossoming friendship is just another case of neocolonial subjugation. Critics point to the fact that Brazil’s economy, after a spurt of industrialization in the second half of the twentieth century—including the development of advanced industries like aerospace and nuclear power—has seen a marked trend toward deindustrialization, becoming increasingly dependent on the export of primary goods. To be sure, catering to Chinese demand has helped Brazil sustain brisk economic growth and a trade surplus, while spurring associated investment. At the same time, the country’s manufacturing industries are stagnating, and the products they once exported to other countries in the region under free trade agreements are being replaced by goods manufactured in China. In fact, this dynamic calls to mind the region’s erstwhile relationship with the United States, which Latin American economists criticized as “neocolonialism.”

China’s exports of EVs and investments in wind and solar power have been touted as keys to Brazil’s transition to renewable energy and achievement of zero carbon emissions. But Chinese investment in agribusiness and oil exploration have contributed to deforestation and environmental degradation, particularly in the northeast. Brazil’s immensely profitable agribusiness sector, with its powerful lobby, exerts a corrosive influence on the nation’s politics. Brazilian universities and research institutes, lured by the offer of much-needed funds, have concluded numerous agreements with Chinese state-owned enterprises that give China the rights to the research results, making it less likely that Brazil will profit from any original technology generated.

Then there is the issue of compatibility in non-economic spheres. In the diplomatic arena, Brazil has long advocated increasing the number of permanent seats on the UN Security Council, an objective shared by Japan and India but opposed by China, which already enjoys the privileges of permanent membership. Other incompatibilities stem from basic ideological differences. Fundamentally, Brazil is a country that values human rights and compliance with international law. Bowing to Beijing’s insistence on noninterference in internal affairs, Brazil has turned a blind eye to China’s habitual violation of human rights, even while grappling with the issue in the IBSA (India-Brazil-South Africa) Dialogue Forum, a consultative framework for emerging democracies. When it comes to basic values, consistency is not a forte of Brazil’s multilateral diplomacy.

Facing the West and Japan

Committed to a multidirectional foreign policy, Brazil has not neglected the Global North. Attending the May 2023 Group of Seven Hiroshima Summit at the invitation of then Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, President Lula evinced a desire to cooperate with the industrially developed democracies while highlighting such global challenges as decarbonization and the fight against poverty. This set the tone for the November 2024 Group of 20 Summit in Rio de Janeiro (on the theme “building a just world and a sustainable planet”) as well as the forthcoming UN Climate Change Conference (COP 30), to be held in Brazil in November 2025. A candidate for accession to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Brazil has also worked hard to align its economic governance with international standards.

Brasilia unquestionably rolled out the red carpet for President Xi following November’s G20 summit, and Japan’s leaders cannot have been pleased to hear Lula speak of Brazil and China as partners working hand in hand for global governance reform, as the two largest developing countries in their respective hemispheres.

But Brazil is a country with many faces. While refusing to submit to any other power, it has shown itself willing to cooperate with almost anyone. Friendship with China need not mean hostility toward Japan. Indeed, Japan enjoys a favorable image in Brazil, which has the world’s largest population of Japanese immigrants and rates their domestic contribution highly. The best way to cultivate productive ties with Brazil as it pursues its vision of a pluralistic world order is to continue identifying mutual interests and working together to achieve common goals.

References

- Carlos Aguiar de Medeiros and Esther Majerowicz (2025) “The Chinese Rise and the Brazilian Economy: Opportunities and Challenges,” Iberoamericana, Vol.46, No.89 (forthcoming).

- Gabriel Cepaluni, Tullo Vigevani, and Phillippe C. Schmitter (2009), Brazilian Foreign Policy in Changing Times: The Quest for Autonomy from Sarney to Lula, Lexington Books.

- Oliver Stuenkel (2016), Post-Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking World Order, Polity Press.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil and President Xi Jinping of China sign a joint statement following their summit in Brasilia, November 20, 2024. © AFP/Jiji.)