Hanshin Three Decades On: Has Japan’s Disaster Response Advanced Since the Kobe Quake?

Disaster- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Same Old Issues Arise in Noto

Near the beginning of December 2024, I got an email from a disaster researcher acquaintance asking for my opinion. The topic was related to the Noto Peninsula earthquake on January 1 that year, and I could sense anger behind the words.

The object of that anger was a 166-page report put out by a government commission looking into issues around the Noto earthquake, which discussed the nature of Japan’s disaster response in light of the disaster. His complaints were related to the report’s discussion of disaster relief, from the initial response activity to setting up evacuation centers, and the gist was: Even with repeated large-scale disasters since the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, including the Niigata Chūetsu Earthquake of 2004, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes, the report simply reiterates the same issues that have arisen time after time. Were none of the lessons of those earlier disasters put to use? Have the national and local governments learned nothing? His argument was not with the report itself. He was simply venting his misery at the fact that it presented nothing more than a repetition of the same old issues.

Reading the report myself, I found it saying the following:

The foundations for maximizing the results of disaster countermeasures are: 1. Raising citizens’ disaster awareness to achieve greater general resilience in the face of large-scale disasters. 2. Improving effectiveness of general planning through revision of regional plans for disaster prevention. 3. Preparing and mastering various manuals and systems, as well as implementing research and training aimed at raising the standard of disaster response capabilities. 4. Implementing further initiatives, such as accelerating digital transformation in the area of disaster mitigation and promoting the use of the latest technology.

All of these issues—with the exception of the fourth, promoting digital transformation to modernize disaster response, which is a more recent development—has been raised and discussed ever since the 1995 Kobe disaster.

I have seen myself how media reporting on the Noto Peninsula Earthquake discussed issues with evacuation shelters and toilets as if they were happening for the first time. It reminded me of what I saw after the Kobe disaster, and I could only regret how the same things keep happening over and over.

Earthquake Intensity On the Rise

Japan is considered a nation with a particularly high risk of natural disasters. I searched Japan Meteorological Agency’s seismic intensity scale database for earthquakes rated at 5 lower, the point at which considerable damage may be expected, and up. In the 30 years before the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, there were 72 such quakes. In the 30 years since then, though, there have been 410 rated a 5 lower or above. It is impossible to make a direct comparison of the numbers, of course, given the improvements in seismic measurement over time, but the historical seismic data for the Japanese archipelago does seem to indicate that Japan has entered a period of heightened seismic activity since 1995.

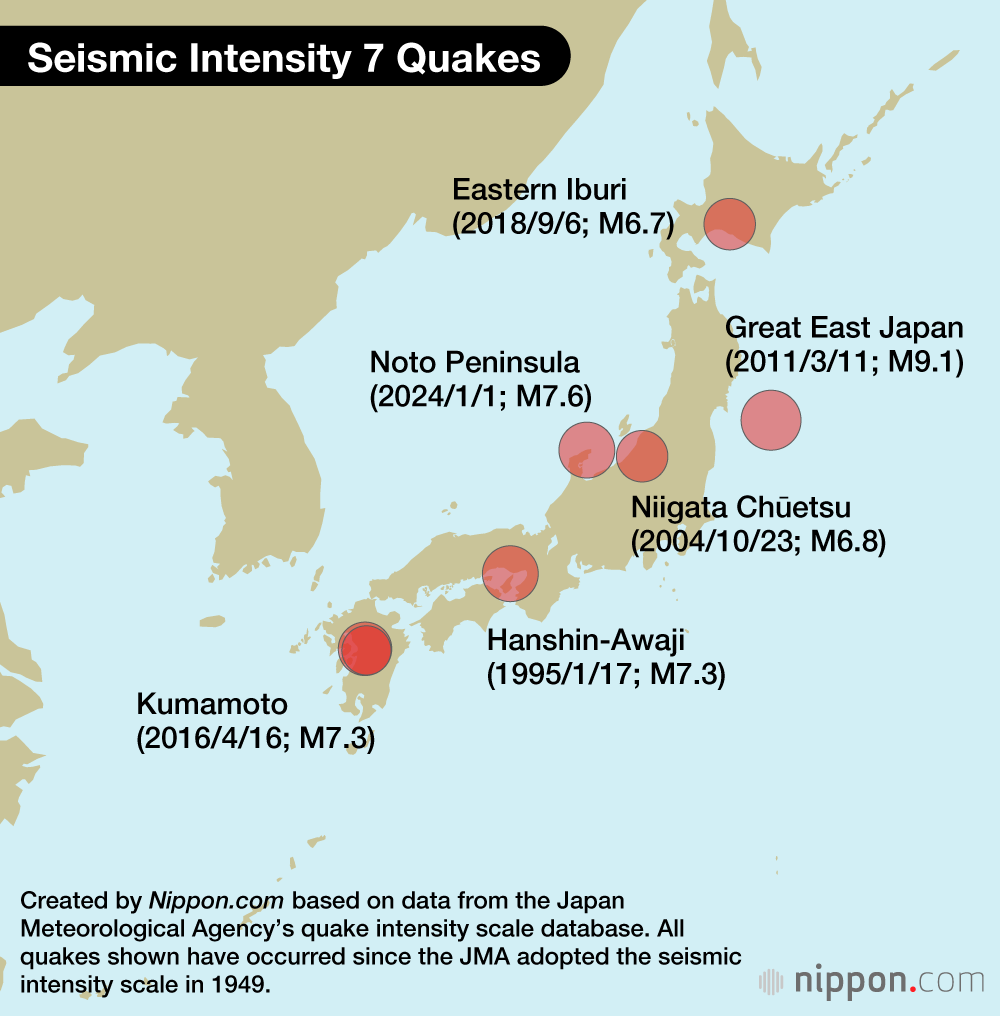

When looking at quakes with local shaking at seismic intensity of 7, which result in major damage, we find there have been seven since the scale was adopted in 1949: Hanshin-Awaji in 1995, Niigata Chūetsu in 2004, Great East Japan in 2011, Kumamoto (twice) in 2016, the Hokkaidō Eastern Iburi quake in 2018, and the Noto Peninsula quake in 2024. They have hit every four or five years since the Hanshin disaster. All except the 3/11 quake have been “intraplate” quakes, which do not occur at the major fault lines between plates. All of us—the national government, local authorities, and citizens alike—must be aware that we are living in a time when earthquakes could strike at any time, and prepare accordingly.

Disaster Response Based on Typhoon Experience

The legal structure around disasters in Japan seem to be based on the idea that “the more damage you face, the more you grow.” With each disaster that strikes, a new law is passed, then revised, and over time adapts to the changing shape of society. However, this legislation never comes in time to deal with the damage that stands at the center of it all, sadly, and those struck by disaster are left with complicated feelings.

The legal structure around disaster in Japan is all founded on the Basic Act on Disaster Management, which was passed in response to the massive Isewan Typhoon of 1959. It sets out comprehensive disaster mitigation organizations and plans, disaster prevention and emergency response measures, reconstruction timelines, and more. Specifically, it describes how the national Central Disaster Management Council must establish a basic plan while management councils at the prefectural and municipal levels are to create regional plans for disaster preparation and response, all to try and prevent or mitigate damage when a major disaster occurs, implement emergency measures, and set a path to recovery efforts.

Because this law was based on a presumption of typhoon damage, it was fundamentally ill-suited to dealing with large scale earthquake damage in highly developed urban centers. So, the law was revised after the 1995 Kobe earthquake. The experience gained in disaster-stricken areas in Kobe helped in reworking regional plans for disaster prevention which had been solely geared for typhoons, resulting in new plans that accounted for earthquake damage. The new Kobe regional plan for disaster prevention was adopted as a model for municipalities across Japan, and many of those municipalities considered how to take their own earthquake response initiatives based on the lessons learned from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

Fires spread across Kobe on January 17, 1995, right after the earthquake. (© Reuters)

Measures Based on Experience, not Formality

The earthquake that struck off the eastern coast of Honshū’s Tōhoku region on March 11, 2011, generated a massive tsunami that caused enormous human loss, with almost 19,000 dead or missing, and did enormous damage across a wide region, including the meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. The damage was also qualitatively different from that of the 1995 quake, with far greater harm from the tsunami rather than the earthquake itself. This is similar to the Jōgan Sanriku earthquake of 869, more than a millennium ago. It truly was an unimaginable tsunami disaster.

It also became the inspiration for another major revision to the Basic Act on Disaster Control Measures.

Just after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I was dispatched from Kobe to the disaster-stricken areas and used my experiences from 1995 to offer advice. I then had the chance to view local governments’ regional disaster plans and was surprised to find that the content looked like it had been simply copied directly from Kobe’s. Nothing was drafted through cooperation with local citizens, investigating and discussing their areas’ disaster history to create something fitting the needs of the local communities; what I saw was truly just a copy of the previous output of disaster consultants elsewhere, pasted in as a formality.

I believe that the main cause for this trend is that administrative and financial reforms have resulted in reduced administrative staff, with only a handful of people now handling disaster measures intended for broad areas. But no matter how textbook-perfect a plan may look, if it doesn’t reflect the realities of local life, it is simply an empty gesture.

Today I wonder whether the same was true of areas struck by the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in January 2024. I think also about how best to convey the experience of disaster victims to the rest of Japan; whether we can help reduce the damage of future incidents; and ways to guide people in the best ways as they pursue recovery and reconstruction from disasters that afflict them. It is the duty of all who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake to help in that way.

Long-Term Visions and Local Needs

Now, three decades after the 1995 quake left Kobe devastated and dark, the beauty of its nighttime scenery makes it all seem like a dream.

Before the earthquake, Kobe had a population of 1.52 million, which fell by 100,000 afterward. Five years later, though, it recovered to 1.49 million, and another five after that it was back to 1.52 million. It remains at about that level today, and industry has also recovered, thanks in part to the reconstruction demand that emerged soon after the quake. Later, new incentives for medical manufacturing and other industries helped drive recovery through industrial restructuring.

The night skyline of Kobe as seen from the sea. The brilliance of the pre-earthquake days has returned. (© Sakurai Seiichi)

I would attribute Kobe’s rapid recovery to a long-term vision, based importantly on issues predating the quake, like a recognition of the need to shift the city’s industrial structure. The meat of the recovery plan formulated after the disaster incorporates the city’s long-term vision, and the speed shown in adopting it was a major factor. It is said that a disaster shows the weakness of a city; I believe that the speed of a postdisaster recovery is in large part a reflection instead of its strength—the presence of a vision addressing issues that existed even before the disaster arose.

However, Japan as a whole is now facing a falling birthrate and aging population, and too much of the economy and population is concentrated in Tokyo. As of 2022, there are 885 municipalities designated as “underpopulated” according to the Act on Special Measures for Supporting the Sustainable Development of Depopulated Areas, which is more than half of the 1,719 municipalities in Japan. This number includes the disaster-stricken areas of the Noto Peninsula. We will have to face these issues when thinking about disaster mitigation and recovery.

The national government has set up an office to prepare for a Disaster Management Agency. Upon launching his administration, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru issued instructions including the establishment of a full cabinet post focused on disaster management, the drastic improvement of planning capabilities for disaster preparation operations, and the crafting of an organization that draws on input from experts in disaster response as it makes its preparations for the future. We hold out hopes for this new agency, but above all, we want it to be an organization built on a long-term national vision that accounts for distinct regional issues.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A photo taken on January 17, 1995, in Kobe’s Higashinada district, showing the ruins of the earthquake-destroyed Hanshin Expressway. © Jiji.)