Rejuvenating Its Tech Industry Is Japan’s Best Bet for Reining in Ballooning Digital Deficit

Economy Technology World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Overseas Dependence

Japan’s appetite for cloud computing, software, marketing tools, and a host of other digital services has grown unabated. While this has fueled the country’s digital transformation, it has also resulted in an ever-widening digital deficit as consumers and corporations shell out money to US-based IT giants like Google, Apple, and Amazon for an expanding suite of services. The situation has set off alarm bells, with many in Japan’s tech sector cynically comparing the situation to modern-day tenant farming as Japanese firms heavily reliant on foreign tech for business hand over a growing share of their revenues to their IT overlords.

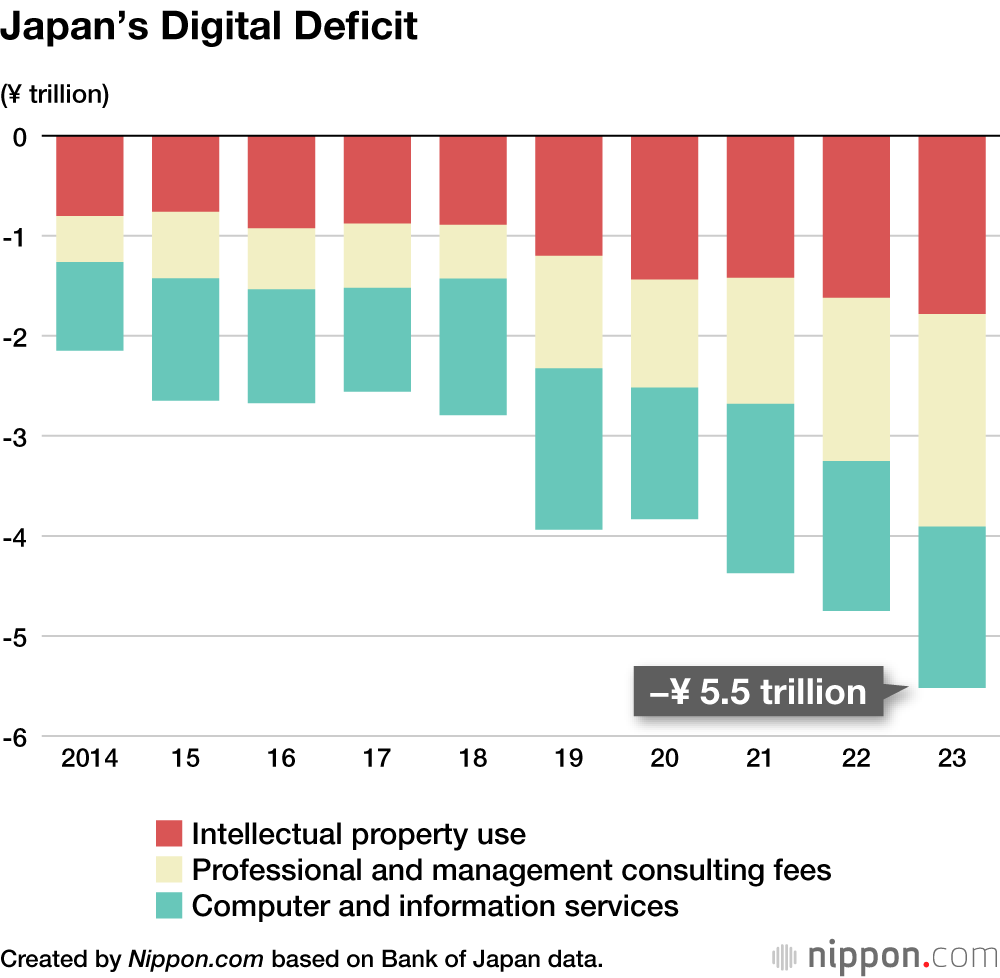

Bank of Japan figures show that the country’s spending on digital services—intellectual property usage, professional and management consulting fees, and computer and information services—has ballooned over the past decade. In 2014 the digital deficit stood at ¥2.1 trillion but had swelled to ¥5.5 trillion as of 2023. The outflow of yen has been most prominent in the form of licensing fees paid by Japanese firms to foreign-based cloud service and software providers. One analyst at Mitsubishi Research Institute, a leading think tank, summed up the situation as the fallout of Japan having ceded the digital service arena to its global competitors.

Once a driver of innovation, the Japanese tech industry over the last 20 to 30 years has grown more and more dependent on software and services from digital companies based overseas, a trend that has only picked up steam with the emergence of cloud computing and the like. Below I consider how Japan fell so far behind in the tech race.

Japan’s IT Decline

There are three major factors behind Japan’s current digital predicament. The first is the inward-facing character of the Japanese tech industry. Early on, Japan’s top firms offered an impressive lineup of operating systems, database management tools, and other software and applications. However, these were largely tailored to fit the niche demands of Japanese corporate clients and there was no real attempt to scan the horizon for opportunities in the broader global market. The largest firms ruled the roost, cornering the sales market by siphoning up the top clients, effectively shutting off avenues for smaller players and new ventures to expand overseas. Having failed to develop globally competitive products, Japanese software makers’ sales now amount to a few billion yen, which is a drop in the bucket compared to the massive sums raked in by the titans of tech.

While Japanese tech innovation stagnated, US-based cloud service providers like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Google, and SaaS (software as a service) firms such as Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Germany’s SAP grabbed up major Japanese clients one after another, with leading IT companies in Japan playing the role of sales agents. Today, sales of their services in Japan range from hundreds of billions of yen to over ¥1 trillion in some cases.

The second factor driving Japan’s digital deficit is that Japanese tech firms ditched innovation for a business model centered around system integration and customization. Rather than developing their own cloud services, they poured their resources into tailoring software to the specific demands of clients.

System development and integration projects were lucrative, and tech firms were content to crank out whatever software their corporate customers asked for. If a client chose to spend a bundle on needless specs, then all the better. These mammoth projects were labor intensive and multitiered, tying up vast swaths of the industry as leading firms brought in subcontractors, who in turn sub-subcontracted smaller companies, and so on.

This inward-looking setup continues to be a drag on productivity across Japan. Take the My Number national identification system for instance, which Japan’s leading tech firms joined forces in developing. The government initially invested several hundred billion yen in its creation, with the resulting streamlining of government services and other benefits projected to have an economic impact upward of ¥3 trillion. The jury is still out on this point, though. Even as new services like the IDs being used in lieu of health insurance cards and driver’s licenses are rolled out, many in Japan wonder whether the touted gains in productivity and convenience justify the costs and manpower in setting up and maintaining the system.

Finally, the low level of IT and digital literacy among corporate executives has been a major barrier to tech innovation. Company heads are often quite happy to blithely follow the advice of hired tech experts or consulting firms who push companies to integrate digital technology into operations, resulting in huge layouts on software and services that strain budgets without bringing the desired dividends. This trend has continued with the arrival of AI, with droves of top brass hastily instructing their teams to blindly adopt the technology for no other reason than that their competitors are using it.

At the other extreme are bean-counting executives bent on keeping spendy tech-related investment in check. Such managers show little interest in building up their IT departments by developing and training employees, but instead task them with creating dedicated systems on the cheap for tech-reliant departments like sales, manufacturing, and product development. In such garroted environments, tech teams languish in supportive roles that ignore their potential as drivers for innovation in the IT and digital realms.

The weakening of its domestic IT industry has subsequently forced Japan to turn to digital service providers based overseas for its tech needs, curtailing its IT independence and causing it to fall further behind the technology curve. Back when Japan represented a 15% share of the global IT market, foreign tech firms lent an ear to their Japanese customers and readily heeded their demands for new features. As Japan’s slice of the digital pie shrank and its overall economic clout dwindled, though, overseas service providers have turned their attention to richer hunting grounds while also raising their fees to bolster their revenues. Japanese firms have had little recourse but to grin and bear it as services once taken for granted, such as Japanese language support, have diminished. The lack of affordable domestic alternatives has worked against small and medium-sized companies in particular, who facing high fees of foreign-based service providers have been slower than their larger corporate colleagues to climb onto the digital transformation bandwagon.

The Path Forward

What, then, must Japan do to revive its digital fortunes? The first step is to rejuvenate the IT industry by loosening the constraints of Japan’s traditional employment system, which would allow the swarms of talented and experienced tech workers concentrated at large corporations to more easily join startups and small-to-medium-sized tech companies. This would disrupt the status quo and allow for new, innovative approaches to emerge.

There is also a need to shift the current business model away from one focused on system integration and customization to a collaborative approach involving both clients and service providers. To compete globally, tech firms need to seek out new business ventures and come up with innovative projects that leverage advanced technologies like generative AI. There are signs that things are moving in this direction, such as information technology and electronics giant NEC Corporation launching an AI drug development business and information technology provider NTT Data teaming up with a sleep analysis service supplier for its Sleep Lab capsule hotel—ventures unrelated to their core businesses.

Another issue is compensation. If Japan hopes to attract the talent necessary to realize its digital transformation, salaries of software developers and other tech specialists will need to be brought in line with the going market rate. According to a 2018 Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry report, the government is looking to double average annual salaries for tech workers from ¥6 million to ¥12 million by 2025, bringing them on par with what workers in the industry earn in the United States. Moderate progress has been made on this front, with some positions in Japan now paying more than ¥10 million a year, but overall salaries still have a way to climb. Ichishi Tatsuya, a senior director and analyst at technological research and consulting firm Gartner Japan notes that the disparity in pay is turning tech-savvy Japanese away from IT careers at home. “Tech just doesn’t offer much allure to members of the younger generations, who are typically drawn to the field,” he says.

Japan must give its tech industry a makeover and rebrand IT as an exciting and appealing field where far from being undervalued cogs, workers are drivers of new, innovative services. Without this shift, it will be hard to attract domestic talent, who will continue to spurn Japanese firms—or the sector as a whole—for better paying positions at tech companies overseas. New ventures like startups along with gifted young software designers and the like should be empowered to take the lead in realizing a true digital transformation that will reverse Japan’s current trajectory and put it on a path toward a digital surplus.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)