2024 LDP Presidential Election

Challenges Ahead for Prime Minister Ishiba’s “First Principles” Diplomacy

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On October 1, Ishiba Shigeru officially became prime minister of Japan. The security environment he faces, however, is no less severe than it was when his predecessor Kishida Fumio came to power three years ago. Most expectations are that—at least initially—Ishiba will follow a similar foreign and security policy approach to Kishida. This includes continuing the implementation of Japan’s Indo-Pacific vision, focusing on strengthening the US-Japan alliance, and pursuing enhanced security cooperation with South Korea.

Over time, however, Ishiba will inevitably seek to add his own flavor to Japan’s diplomatic approach. As articulated in the lead-up to the Liberal Democratic Party presidential election, Ishiba’s recent foreign and security policy outlook was characterized by two themes. One was his desire for a collective security system in the region based on his proposed creation of an “Asian NATO.” The other was Ishiba’s interest in reconfiguring the US-Japan alliance to promote greater equality “befitting an independent sovereign nation.”

Both themes derive from Ishiba’s well-known idealist, or even “fundamentalist,” approach to policy issues. He is known for political thinking based on reasoning from first principles and insisting on adhering to the conclusions he comes to. At times, this can result in him adopting overly ambitious diplomatic positions based on a clear sense of how “things should be” in terms of protecting Japan’s national interests.

Having finally succeeded on his fifth attempt at becoming LDP president, as prime minister Ishiba finally has the opportunity to pursue his strategic vision for Japan. There will be no shortage of challenges for him to overcome, however. For example, his desire to evolve the US-Japan alliance while attempting to strike a strategic balance in Japan’s relations with the United States and China by improving Japan-China relations may well work at cross-purposes. His principled thinking may not necessarily serve him well as complex and contradictory realities emerge in response to Ishiba’s “first principles” diplomacy.

Ishiba’s Asian NATO Ambition

Ishiba has long advocated for moving toward the creation of an Asian equivalent to NATO. Ishiba sees the current “hub-and-spoke” security model as suboptimal for deterring conflict in the region today. Based on Cold War security arrangements, the model saw American allies such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines (the “spokes”) contribute to regional security only through the central “hub” of the United States.

Ishiba argues, however, that Japan should pay greater attention to relative American strategic decline. As such, he wants to evolve the regional security relationships by moving toward something similar to NATO’s arrangements which are based on collective, “networked” security. Not only would American allies come to each other’s assistance in times of need, but organic security cooperation among these allies and other like-minded countries would gradually be strengthened during peacetime. Such an approach would build on and elevate the various “minilateral” frameworks that have recently emerged in the region (such as the US-ROK-Japan trilateral and the “Quad” of Japan, India, Australia, and the United States). They would become something much more akin to a treaty alliance based on collective security.

This is easier said than done. Japan itself would be faced with various problems in implementing such a vision. After all, such a commitment to collective security could automatically oblige Japan and its Self-Defense Forces to come to the front-line assistance of any Asian ally that was attacked irrespective of the danger Japan faced. The SDF would very likely be involved in combat in a way that goes far beyond the limited type of collective self-defense permitted by Japan’s current legislative arrangements and constitutional conventions around the use of force.

When pressed on this point in an interview on TV Asahi on the day he was elected LDP president, Ishiba retreated somewhat by saying, “It is not about deploying combat troops overseas but the formulation of a system that enhances mutual assistance and a commitment to working together to enhance regional security before events get to that point. It is necessary to explore how to do this within Japan’s legal framework.” At the same time, Ishiba did stress that “ultimately, the reason NATO did not help Ukraine as Russia prepared its attack was because Ukraine was not a NATO member.”

Ishiba has consistently warned both the Japanese public and policymakers about complacency. In his view, if Japan lacks a strong will to defend itself autonomously by the necessary means, then it must look at acquiring strong allies. However, in the context of relative American strategic decline, being solely focused on the bilateral relationship will no longer work. As such, the optimal approach for protecting Japan is to formulate a collective security framework among allies. He is not afraid to speak directly and challenge the Japanese public using this logic. At the same time, the common refrain in Tokyo that “Today’s Ukraine is tomorrow’s Asia” rings hollow to Ishiba. He has often expressed frustration with what he sees as a lack of urgency among the political class and strategic policymakers to really address Japan’s security challenges.

The Risks Surrounding a SOFA Revision

Ishiba has also long spoken about the need to enhance the mutuality and thus equality of Japan’s security arrangements with the United States. This could at first include a potentially controversial review of the Status of Forces Agreement governing the presence of forward-deployed American forces and their use of facilities in Japan. Ishiba certainly did not shy away from discussing a SOFA review during campaigning for the LDP presidency.

For example, in a September 17 speech in Naha, Okinawa, Ishiba touched on the 2004 crash of a United States military helicopter at Okinawa International University. At that time, Ishiba was head of the Japan Defense Agency (the forerunner to the current Ministry of Defense). Ishiba told the crowd that “The American military handled the whole response operation and even investigated and recovered the wreckage themselves. Is that something we can allow as a sovereign nation?” At his first press conference as the new LDP president, Ishiba noted that the Okinawa chapter of the LDP itself has requested a SOFA review, and thus as the party’s president he could not ignore the request.

Ishiba also proposed the establishment of Japan’s own permanent military base in the United States. To his mind, this would strengthen the US-Japan alliance and enhance the operational competency of Japan’s own military forces. The proposed base would not explicitly be for forward defense purposes like the United States military presence in Japan, but for training purposes. The Ground and Air Self-Defense Forces in particular would be able to make advantageous use of America’s large and well-developed bases and infrastructure by conducting a wider variety of exercises than they can in the more constrained environment in Japan.

In order to accomplish such an objective, however, Tokyo would need to negotiate its own “SOFA” arrangement with Washington. In such a case, the expectation is that a Japanese SOFA for a permanent SDF presence in the United States would contain much the same provisions as the current SOFA for US forces in Japan does.

Ishiba’s own perspective is that the current SOFA is part of the bedrock of the alliance framework centered on the US-Japan Security Treaty. In effect, the issues surrounding any enhancement of SOFA arrangements would inevitably raise issues around collective self-defense and, ultimately, constitutionality. Indeed, Japan’s inability to exercise the right of collective self-defense in its entirety is the very reason why the US-Japan Security Treaty remains asymmetrical and cannot simply be upgraded and renegotiated. For Japan to forge an equal alliance with the United States and see a reduction in the size of American forces in Japan, Ishiba understands that Japan must embrace the full exercise of the right of collective self-defense; only then can the asymmetry of the Security Treaty be addressed.

In addition to Japan’s own constitutional restrictions, any substantive and meaningful review of the current SOFA would also require a great deal of time and significant political capital. If Ishiba, by sticking to his principled views, hastily demands an overhaul of the US-Japan Security Treaty in a way “befitting a truly independent nation,” he might do little more than make the American government wary of engaging in the process with his administration.

During his press conference after becoming LDP president, a reporter asked Ishiba when he would raise this issue with the Americans in light of his campaign comments. Ishiba avoided giving a clear answer by saying that he was in no position to set deadlines. This reflects the reality of the situation but may also be due to a secret agreement Ishiba is purported to have made with Kishida in exchange for his support in the LDP run-off, where Ishiba came from behind to defeat Takaichi Sanae. Part of this agreement apparently included a promise to not immediately review the SOFA arrangements.

Ishiba (in black) during his honorary retirement ceremony after the end of his tenure as defense minister on August 4, 2008. (© Kyōdō)

Can Ishiba put China-Japan Relations Back on Track?

Ishiba also believes improved diplomacy with China is an urgent issue. This, too, is fraught with pitfalls for his administration.

One of the pending issues is China’s ban on imports from Japan of marine products due to the release of ALPS-treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. Following a steady improvement in Japan-China relations since the November 2023 summit meeting between Prime Minister Kishida and President Xi Jinping, Beijing and Tokyo reached an agreement in principle to resume imports in stages. However, public sentiments in both countries rapidly soured following the fatal stabbing of a 10-year-old Japanese boy in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, on September 18—the anniversary of the 1931 Manchurian Incident. The Chinese authorities, however, denied that the incident was emblematic of anti-Japanese sentiments in China and insisted that it was an incidental, nonpolitical crime.

This will likely put on hold any moves by Ishiba to pursue more constructive diplomacy. Furthermore, during the LDP presidential race, Ishiba made it clear that as prime minister he would not waffle on China-related issues important to Japan just because an agreement to resume imports had been made. He would say what needed to be said to Beijing.

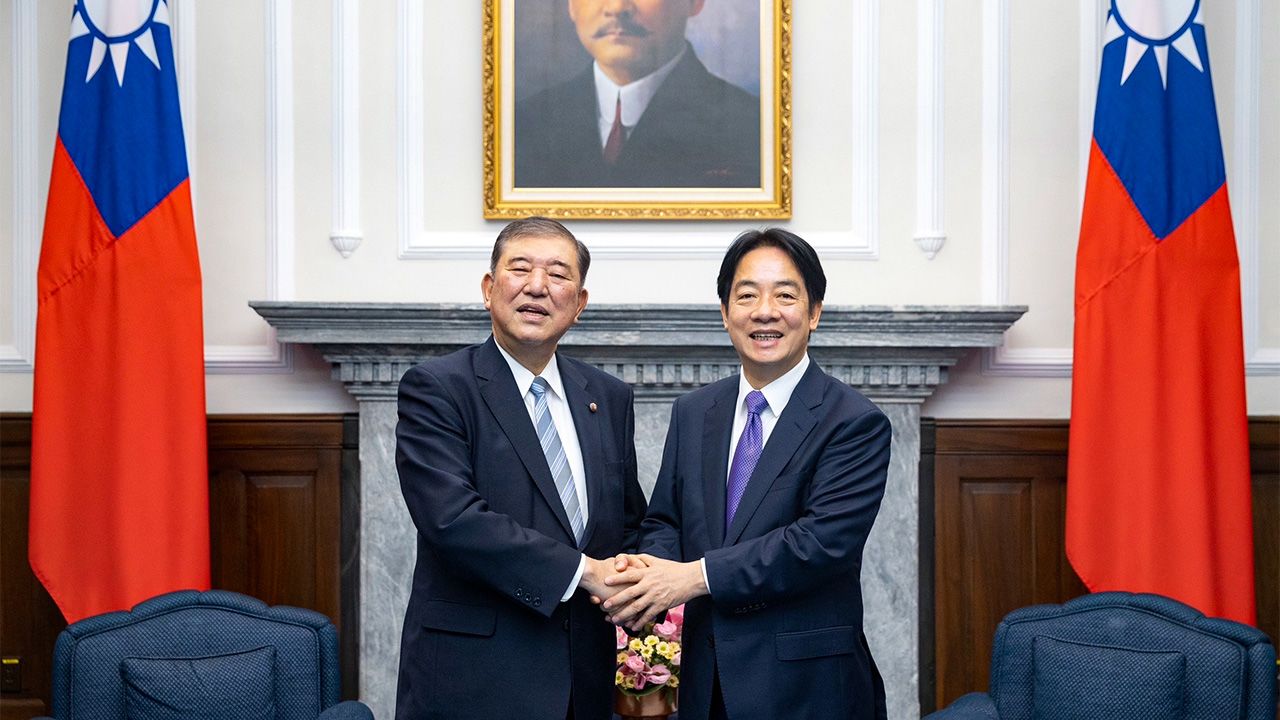

As it was, Beijing was already growing increasingly wary of Ishiba. Together with a cross-partisan group of lawmakers, Ishiba visited Taiwan in August to meet with Taiwanese leaders. Ishiba met with President William Lai during his visit, which sent shockwaves through the region.

While Ishiba was in Taiwan, Prime Minister Kishida announced that he would not be running for reelection in the LDP presidential race. As potential candidates to replace Kishida as prime minister started maneuvering, Beijing took advantage of the political vacuum and increased the intensity of its military provocations as a way to signal its dissatisfaction.

On August 26, the day before the visit to China by Nikai Toshihiro, chairman of the Japan-China Parliamentary Friendship League (and former LDP secretary-general), a Chinese military Y-9 intelligence-gathering aircraft flew over Nagasaki Prefecture’s Danjo Islands and violated Japanese airspace. On September 18, the Liaoning, a Chinese naval aircraft carrier, entered Japan’s contiguous waters between the islands of Yonaguni and Iriomote in Okinawa Prefecture. Both events were purportedly the first such violations of the kind. On the same day as the Liaoning violation, North Korea launched several short-range ballistic missiles. Chinese and Russian naval vessels also jointly navigate around Japan, and on September 23, a Russian patrol aircraft violated Japanese airspace three times north of the island of Rebun, Hokkaidō.

Thus, the already severe security environment in East Asia has only worsened during the time Kishida announced his intention to step aside and Ishiba assumed the role of prime minister. Recognizing the sensitivity, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has proactively put together a busy diplomatic schedule for the new prime minister. Prime Minister Ishiba is due to attend the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Summit in Laos on October 9–11. Various meetings between regional leaders often take place on the sidelines of the ASEAN gathering. Chinese Premier Li Qiang is also scheduled to attend the summit, and Ishiba and MOFA are eager to organize what would be the first Japan-China summit meeting since the September 18 fatal stabbing incident.

Furthermore, Prime Minister Ishiba is scheduled to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Lima, Peru, in mid-November and the G20 Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, soon after. There are high hopes that a summit meeting with President Xi Jinping will take place on one of those occasions. For Beijing, there is a desire to engage Japan—which still plays an important role in China’s economic plans—at a time when the Chinese economy has started to stagnate in part due to the real estate slump. In this context, all eyes will be on Prime Minister Ishiba, who has largely adhered to his principles in his dealings with China to date, and how he will negotiate this sensitive time in diplomatic relations.

Critical Personnel Decisions

As noted, Ishiba is ultimately expected to inherit the diplomatic approach pursued by Kishida during his three-year term as prime minister. The Kishida administration oversaw stable relations with the United States and put Japan-South Korea relations on a steady footing. However, if at some point Ishiba is too assertive in pursuing his preferred policies based on “first principles” diplomacy, tensions and in-fighting over policy between the prime minister’s office and the defense and foreign ministries are likely to occur, undermining his administration.

There are other unpredictable factors that could shake the Ishiba government. These include the dissolution of the Diet and the potential risk to Ishiba if the LDP underperforms in the election scheduled for October 27. Little more than a week later is the US presidential election, where a second Donald Trump administration remains a distinct possibility.

Prime Minister Ishiba therefore needed to quickly solidify a foreign policy team of competent personnel. Ishiba’s choices for the foreign affairs, defense, and economic security portfolios were all seen to be vital, and it was no surprise that he chose candidates with previous cabinet and foreign policy experience. So too was Ishiba’s decision about what to do with National Security Advisor Akiba Takeo, who is responsible for advising the prime minister as well as running the National Security Secretariat. Akiba has been a crucial support pillar for the Abe Shinzō, Suga Yoshihide, and Kishida administrations in foreign and security policy. As NSA from 2021, Akiba demonstrated unrivaled coordination skills at the interface between bureaucrats and politicians. Ishiba’s recent decision to reappoint Akiba and much of Kishida’s National Security Secretariat staff may well be a critical factor determining the success or failure of the Ishiba administration’s diplomacy.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Ishiba Shigeru, at left, and Taiwanese President William Lai shake hands at the Presidential Office in Taipei on August 13, 2024. During this visit, Prime Minister Kishida announced his decision not to run for reelection as LDP president. Image courtesy of the Office of the President, ROC. © Jiji.)