Dark Skies Ahead for Shinkansen Network Expansion

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Lingering Issues with the Storied Shinkansen

The October 1, 1964, opening of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen line connecting Tokyo and Osaka changed rail history. The conventional Tōkaidō main line carried multiple passenger and freight trains every day, but had grown unable to handle the growth in demand that came with the expanding economy. The Japanese National Railways approached the problem with a new dedicated line: a different gauge standard of 1,435 mm carrying high-speed trains travelling over 200 kilometers an hour, achieving a dramatic increase in transportation capacity.

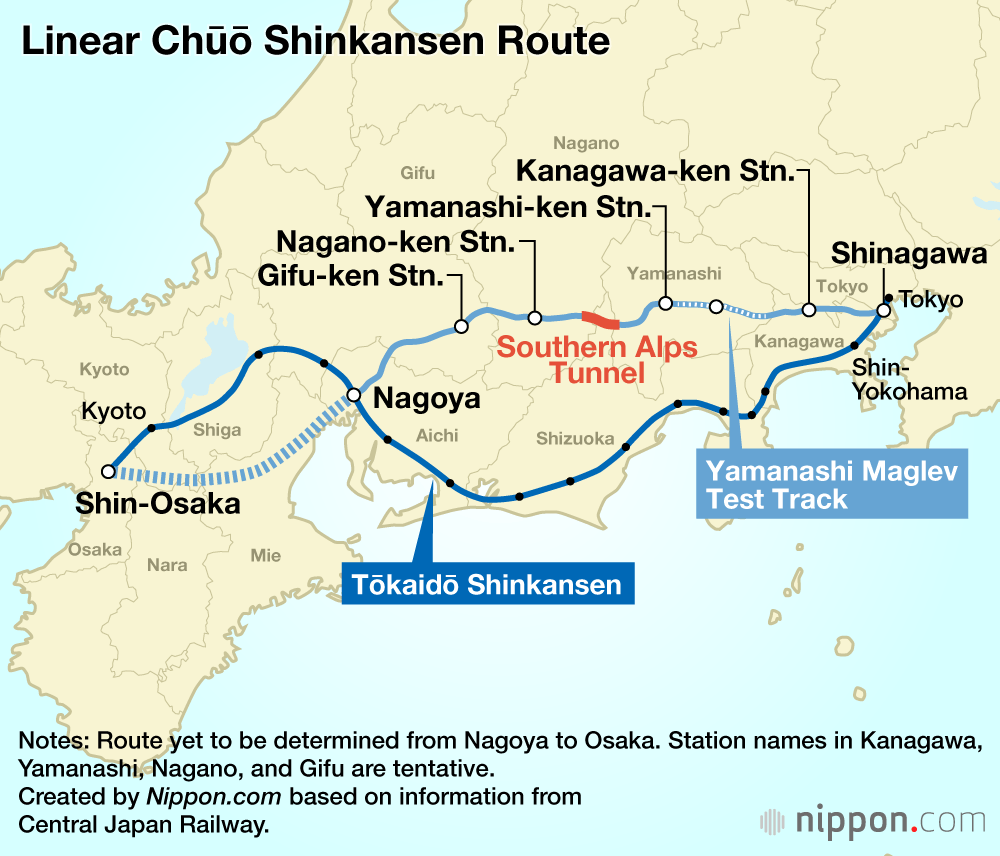

Now, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen runs an hourly maximum of more than a dozen Nozomi superexpresses, along with many other trains with more frequent stops, on a highly precise schedule. In an effort to further alleviate congestion and reinforce backup functions in the case of disaster, like the predicted Nankai Trough earthquake, as well as to increase travel speed, Central Japan Rail is now constructing the Linear Chūō Shinkansen line. This line will run maglev trains at over 500 kilometers an hour, making the trip from Tokyo’s Shinagawa terminal to Nagoya in as little as 40 minutes, or Osaka in 67. You could see this effort to create new standards to increase speeds as a repeat of the same concept of 60 years ago.

The Linear Chūō Shinkansen has the potential to reshape society by, for example, uniting the nation’s three largest metropolitan areas of Kantō, Kansai, and Aichi in between. But issues are piling up on the road to completion. The construction budget to connect Shinagawa to Osaka has topped ¥9 trillion, with JR Central taking the lead on both construction and operations. The plan is to fund construction using both cash flow from the Tōkaidō Shinkansen as well as government funding. However, the section between Shinagawa and Nagoya that is now under construction has already gone ¥1.5 trillion over budget. Predictions are that the final total will go even higher.

Construction is also failing to proceed as planned. The Southern Alps Tunnel passing through Shizuoka Prefecture was held up when former governor Kawakatsu Heita refused to approve it due to predicted impacts on the flow of the Ōi River. Although newly elected governor Suzuki Yasutomo has approved boring surveys, the Shizuoka section remains untouched. Sections in other prefectures have also faced difficulties in securing locations, and construction and has been plagued with issues such as delayed reports of construction troubles to local officials.

Construction on the Shizuoka section is projected to need around 10 years, and the original planned 2027 opening date for the Shinagawa to Nagoya section is now expected to come in 2034 at the earliest. The government has set a goal to open the section west of Nagoya all the way to Osaka in 2037 by carrying out construction on that section simultaneously. However, JR Central claims that staffing difficulties in planning and construction are making simultaneous construction a challenge.

Progress on Expanded Lines 90% Complete

Progress on the Seibi Shinkansen (defined below) proposed after railway privatization in 1987 has been led by the government’s Japan Railway Construction, Transport, and Technology Agency (JRTT, formerly Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation). Some critics say that the issues that JR Central has been experiencing in building the Linear Chūō Shinkansen line came about from a lack of construction know-how because of that. The fact that the company has still insisted on funding and managing construction itself indicates its desire to avoid political interference in the project.

The bullet train network has had deep ties to government ever since the first Tōkaidō Shinkansen line opened. As construction on the San’yō line moved forward in 1970, the Diet passed the Nationwide Shinkansen Development Act, which included a plan for a network covering all of Japan. In 1971, the government approved plans and construction started on the Tōhoku, Jōetsu, and Narita lines—although the Narita line was cancelled in 1987.

Then, in 1973, expanded plans for 5 lines and basic outlines for 12 “standard plan” lines—to serve areas like Shikoku, eastern Kyūshū, and the Japan Sea coast—were added. The plan was spearheaded by Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei, who had called for “A Plan for Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago.” The planned lines all strongly reflected the intent of Tanaka and other powerful figures in the Liberal Democratic Party.

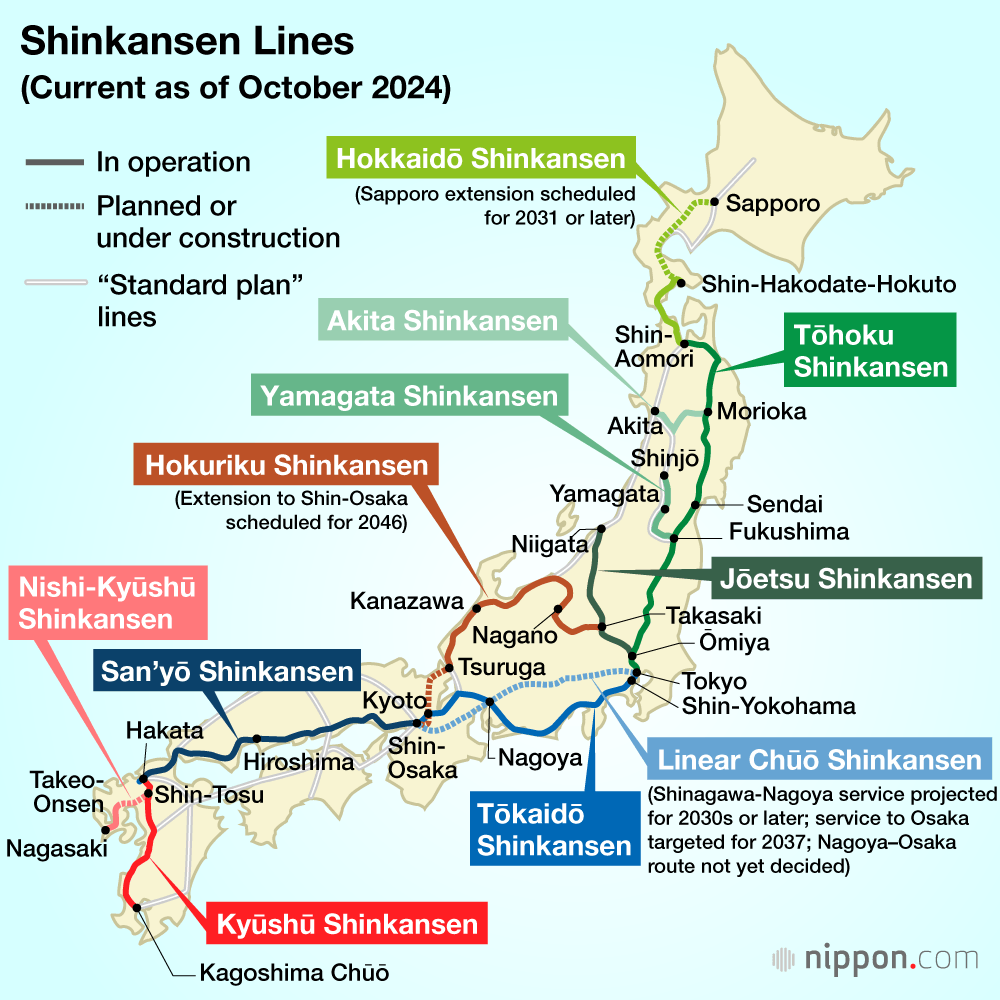

The expanded lines from 1973 that actually saw construction begin were the Tōhoku Shinkansen from Morioka to Shin-Aomori; the Hokkaidō Shinkansen from Shin-Aomori to Sapporo; the Hokuriku Shinkansen from Takasaki to Shin-Osaka; the Kyūshū Shinkansen from Hakata to Kagoshima Chūō; and the Nishi Kyūshū Shinkansen from Shin Tosu to Nagasaki. These five lines, comprising about 1,500 kilometers of track, are known as the Seibi Shinkansen.

The Tōhoku Shinkansen between Ōmiya and Morioka and the Jōetsu Shinkansen between Ōmiya and Niigata began operations in 1982, but work on the Seibi Shinkansen was frozen in 1982 after the Japanese National Railways’ finances worsened. The political world urged completion, though, and worked out a scheme in which the Shinkansen would be built as a public works project and leased to JR, in a scheme splitting operations from ownership. The construction freeze was lifted in January 1987, just before JNR was privatized.

In the 27 years between when the first section of the Hokuriku Shinkansen (Takasaki to Nagano) opened in 1997 and the launch of the section from Kanazawa to Tsuruga in 2023, 1,121 kilometers of the Seibi Shinkansen have come into operation. Construction is underway on the 212 kilometers of the Hokkaidō Shinkansen from Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto north to Sapporo, meaning that nearly 90% of the planned Seibi Shinkansen lines are complete. However, the remaining 140 kilometers on the Hokuriku Shinkansen between Tsuruga and Shin Osaka and the 50-kilometer Nishi Kyushu section between Shin Tosu and Takeo Onsen show no signs of progress.

Uncertainties Cloud the Western Japan Route Selection

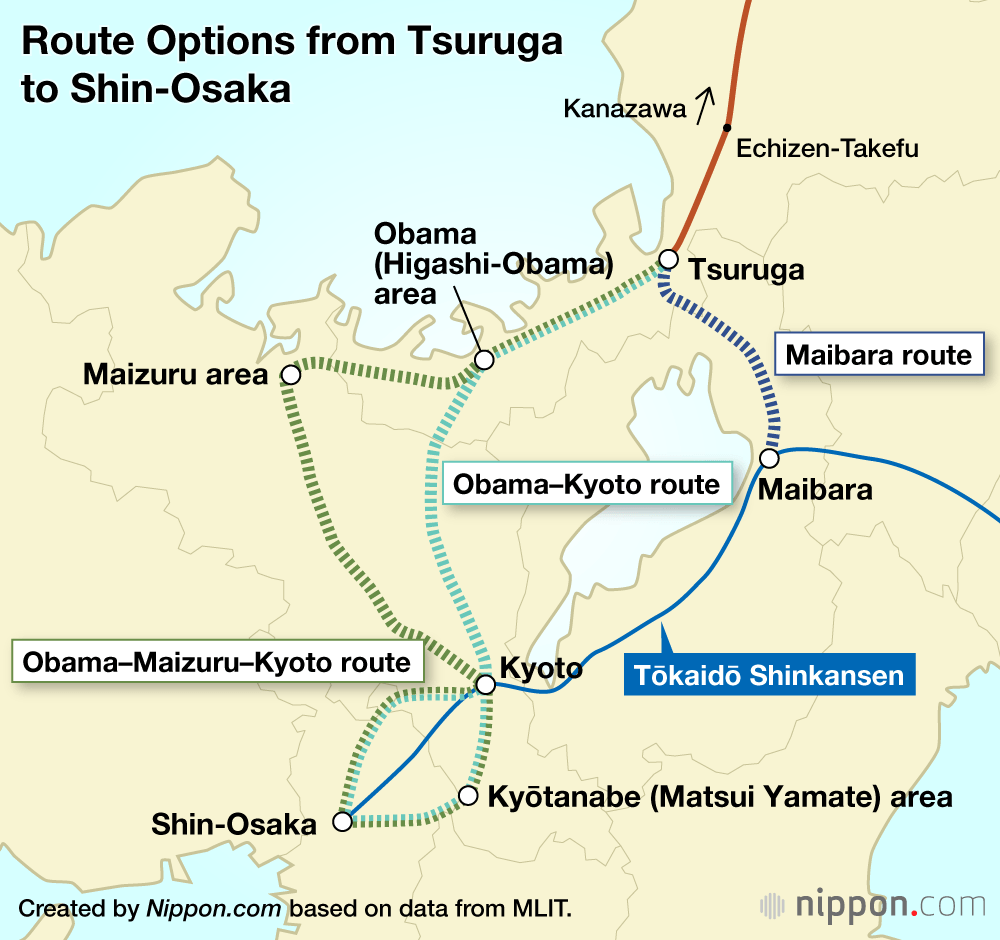

The biggest controversy right now is over the Hokuriku Shinkansen route between Tsuruga and Shin-Osaka. The ruling party’s Seibi Shinkansen Construction Project Team initially proposed three possible routes for it: the Obama–Maizuru–Kyoto route, the Obama–Kyoto route, and the Maibara route. The final choice was the Obama–Kyoto route, for its convenience, speed, and support from JR West. The initial proposal was a construction time of 15 years starting in 2030, with operations commencing around 2046.

JRTT began with an environmental assessment of the proposed areas in 2019, and it found that construction around Kyoto and Shin Osaka stations would be very difficult due to the many existing tracks and surrounding buildings, and that extensive groundwater measures and excavated soil management would be required. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism informed the government that any of the three proposed routes around Kyoto would actually take roughly 20 to 28 years, and operations would begin in the 2050s at the earliest.

The initial plan for the Seibi Shinkansen laid out five necessary conditions for their construction: securing a forecast for stable funding, profitability, return on investment, JR’s agreement as operating entity, and consent from local municipalities for parallel surface train lines to be removed from JR operations. Within them, a particular emphasis is placed on ensuring that the benefit/cost (B/C) ratio—balancing costs like construction expenses etc. with benefits like travel time reductions—is 1 or higher.

The projected total project costs for the Obama–Kyoto route in 2016 came to ¥2.1 trillion, with a B/C of 1.1. However, in the eight years since the route was finalized, material and staff costs have risen, so the total project cost has more than doubled and the B/C stands around 0.5. The current structure does not satisfy the basic conditions, leading the Japan Restoration Party, which exerts powerful political influence in western Japan, to push for the route to be shifted to the Maibara option, because it maintains a B/C of over 1.

The problem of parallel conventional train lines also remains. In principle, the line subject to separation would be the Kosei Line between Tsuruga and Shin Osaka, with its Thunderbird express train. Shiga Prefecture and local communities along the route oppose this, since they will see a rise in fares and other inconveniences without actual access to the Shinkansen route inside the prefecture, which means it is unclear if the requirement for local consent will be met.

Opposition to the Nishi Kyūshū Shinkansen

The Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen, which began partial operation in 2023, is facing similar problems. The original plan was to run free gauge trains, which can switch between conventional rails and Shinkansen gauge, on a full Shinkansen standard line from Takeo Onsen to Nagasaki and on conventional lines from Hakata to Takeo Onsen to reduce construction costs and achieve direct service without the need to change trains. However, the project was abandoned due to difficulties in developing FGT technology. The line currently runs with cross-platform interchange to a conventional limited express train at Takeo Onsen Station.

National government officials and Nagasaki Prefecture see the transfer system as a limited-time fix, and want to proceed with building a full standard Shinkansen line between Shin Tosu and Takeo Onsen. However, Saga Prefecture opposes the change. That is because connection between Hakata and Saga station is already as fast as 35 minutes, so it does not want to be saddled with part of the massive costs to build the line for the limited benefit of a 10-plus-minute time saving. Saga officials are also protesting the added issues that would arise if JR walked away from operating the Nagasaki Honsen line as part of its launch of this new Shinkansen stretch.

Long Term Vision Needed

In the end, the success or failure of Shinkansen construction depends on the balance between burden and return. Much of the Seibi Shinkansen line network has connected urban areas with outlying regions, and those local communities have welcomed the connections with major cities in hopes of tourism growth. Now, the Hokuriku Shinkansen is planning an extension from Tsuruga to Kyoto and Osaka. The extensive costs and long periods needed for construction in urban centers place a heavy burden on residents, while the divestment of conventional lines impacts a great many riders. It is hard to see the city side being so welcoming in such a case.

Another issue with Seibi Shinkansen expansion is renewing existing lines. It has been nearly 30 years since the 1997 opening of the current section of the Hokuriku Shinkansen between Takasaki and Nagano, when it was built as a public works project, meaning it is nearly time to consider a major update to facilities. The loan to JR for the Seibi Shinkansen construction was originally set at a 30-year fixed rate; the Transport Ministry is planning to extend the repayment period for the loan covering construction of this portion of the line, allowing it to help fund the ballooning costs of the Kanazawa–Tsuruga stretch as well. There has been no decision on how the loan will be administered, though, or how to manage the burden of paying for any major renewals.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement to promote the “standard plan” lines of the Shikoku Shinkansen, San’in Shinkansen, and Ōu Shinkansen lines as part of the next Seibi Shinkansen phase. However, with Japan’s sweeping population decline, demand for travel—especially in rural areas—is shrinking, and the benefits of Shinkansen development will diminish accordingly. At the same time, it will become increasingly difficult to meet the B/C ratio conditions as inflation, labor shortages, and stricter laws and regulations—such as more stringent earthquake resistance standards and environmental measures—lead to higher construction costs.

The national administration is ready to extend the loan to 50 years, but taking this as a source of easy funding for building new lines might actually make preserving the Shinkansen network more difficult. The government will need to present a long-term vision that considers the balance between new construction and renewal.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photos: The Hokuriku Shinkansen, top, and Linear Chūō Shinkansen. © Kyōdō.)