Safety and Convenience: How the Shinkansen Changed Japan

Society Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Zero Fatal Passenger Accidents

From the very first run of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen on October 1, 1964, until the present day, there has never been a single derailment or collision on the entire full-standard Shinkansen rail network resulting in a passenger fatality. This safety record stands testament to the many safety systems developed and introduced for Japan’s “bullet trains.”

The most important of all those is the Automatic Train Control system. When the train approaches another train on the same track, or a stop along the line, the ATC automatically reduces its speed. The driver only needs to make fine adjustments to then stop the train at the designated spot. The result is that, in principle, the chance of two Shinkansen trains colliding is essentially zero, and in fact there has never been such a collision in the network’s history.

The ATC also contributes to the network’s reliable operation. The Shinkansen does not run only on clear, sunny days, when forward visibility is good. The ATC allows trains to reach their top speeds of over 200 kilometers per hour no matter how bad the weather or how dark the night.

Even in the modern day, when rail travel has become safer overall, there are still incidents of trains colliding with cars at railroad crossings. The full-standard shinkansen lines use only separated crossing grades, eliminating the chance of crossing collisions. There are also systems that will stop trains if a car falls from a bridge over a shinkansen line, for example.

In most of the developed world, collision safety measures are required for all trains, and there are stringent safety standards for any rolling stock introduced for high-speed rail like the Shinkansen. However, there are no standards related to collision safety for rolling stock on Shinkansen lines. All the trains are designed around the presence of safety measures like ATC and separated grades, which have essentially eliminated the danger of collisions.

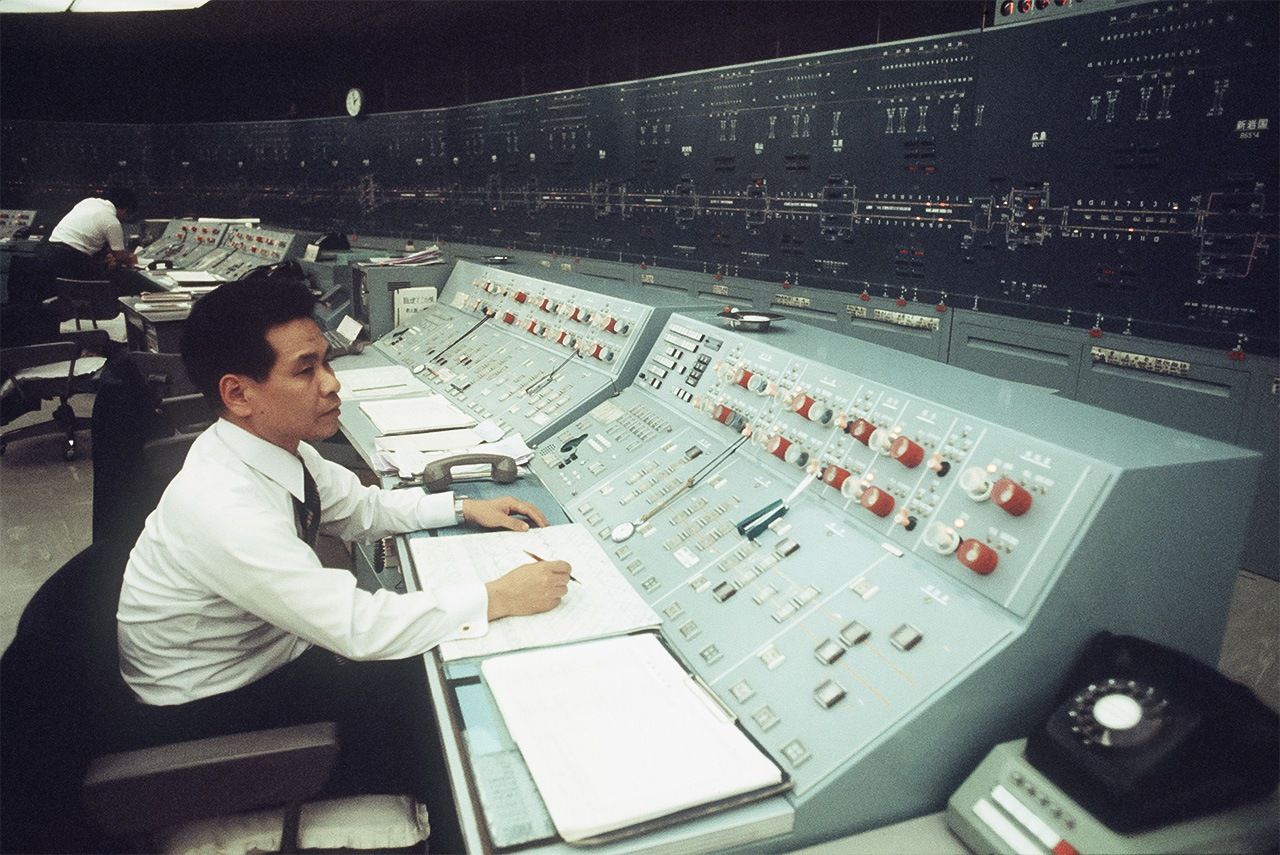

Tokyo’s central control center for the Shinkansen network, taken June 3, 1977. (© Jiji)

The Shinkansen offers long distance mass transport in short times. If, as had been the case for pre-Shinkansen railways, monitoring and route designation had been left to each individual station, it would create an immense burden and could have negative impacts on safety and reliability. Concentrating the tasks of monitoring and directing train operations in one location is a better choice and makes switching and routing more efficient. That is what inspired the adoption of Centralized Traffic Control from the Tōkaidō Shinkansen’s inception, and it has now been widely adopted for conventional railways as well.

The Japanese National Railways faced a massive budget shortfall during the Tōkaidō Shinkansen’s construction, and there was talk of delaying CTC adoption in favor of distributing the burden of monitoring and routing trains to the individual stations. The story goes, though, that then-JNR director Sogō Shinji ordered that the budget be adjusted to include CTC, in recognition of Japan’s tendency for frequent train stoppages amid its many natural disasters.

Changes in Travel and in Daily Life

With all its many safety measures and convenience, the Shinkansen has earned a place in daily life the same as urban commuter trains. Unlike airplanes, there is no need for staff to make preflight safety presentations or even for passengers to use safety belts. It seems highly unlikely that anyone ever buys travel insurance before taking a Shinkansen trip, either. Although Shinkansen travel takes comparatively longer than travel by plane, its greater convenience has contributed to its enormous impact on Japanese people’s domestic travel.

People’s movement between the capital area and Kansai in particular has changed dramatically. Before the opening of the Shinkansen, it took at least six and a half hours to get from Tokyo to Osaka by rail. The first Shinkansen runs shortened that to four hours, and from 1965 the time was cut by over half to three hours and ten minutes.

The Shinkansen seems also to have revealed latent demand for transport. Before the Shinkansen, there were seven round trip runs making for 14 daily express trains between Tokyo Station and Osaka Station, but after, the number jumped to 30 round-trip runs, for 60 trains every day. The Shinkansen debuted in the middle of Japan’s post–World War II economic boom, which probably contributed to the huge increase in demand for trips between these urban centers, but one can also assume that cutting the time needed for that long trip removed a major barrier for everyone.

It also changed familiar culture. The growth of the owarai comedy of the Kansai area around Osaka, once a purely local performing art, into a nationwide phenomenon was spurred by the Shinkansen. One leading comedian has commented that before the fast trains started operation, comedians’ popularity was limited largely to Kansai.

The convenience of the Shinkansen meant that entertainers based in Kansai could more easily work at key television stations in Tokyo broadcasting nationwide. That same comedian says that there were times when they made two round trips between Shin-Osaka and Tokyo Station in a single day. That kind of travel between airports, which are almost always well outside the city center and require boarding procedures and security checks, is simply impossible. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that the Shinkansen changed the shape of comedy in Japan.

A change also came to professional baseball. The appearance of the Shinkansen significantly lightened the burdens on players touring the country. The last period with no Shinkansen would have been the 1964 season, and a look at the play schedule for that year shows that there were basically three games on weekends, with another three from Tuesday to Thursday, while Mondays and Fridays were travel days. Sundays were usually double-header days, allowing for the three-game weekends.

In the 1965 season, after the Shinkansen started running, the number of double headers on Sundays fell dramatically, as teams could play on Fridays instead. Double headers continued to fall off until they essentially disappeared by the mid-1970s.

The increased use of air travel certainly contributed to some changes in the pro baseball schedule, but the fact is that many players chafed under the burdens of double headers, and they surely welcomed the convenience offered by the Shinkansen.

World Expo Encouraged Growth

I would like to also discuss how the Shinkansen contributed to the success of an event of national importance. From March 15 to September 13, 1970, Osaka was host to the Japan World Exposition. The success of this massive event, which attracted over 64 million visitors, was of course due mostly to the Expo’s content and the Kansai area’s inherent potential as a tourist area, but the Shinkansen’s mass transport capabilities were also a significant contributor.

It was not only used by visitors coming from across Japan, particularly from Tokyo. It also became a draw itself for visitors from overseas who learned about the new train system through the global exposure of the Expo.

The iconic Tower of the Sun stands over the crowded Expo venue in the Senri hills of Osaka Prefecture. (© Jiji)

Shinkansen passengers headed for the Expo peaked in August 1970 at around 370,000 people a day. Given that the average daily passenger numbers on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen line just before the COVID-19 pandemic were around 470,000, that was an astonishingly large number. People of the day referred to the Shinkansen as “a mobile Expo pavilion.” Visitors to the Expo shared their pleasant travel experience on the Shinkansen along with their stories of the Expo itself, and soon Shinkansen travel became a matter of course.

The transport revolution ushered in by the Shinkansen changed the very shape of life in Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: An N700S Shinkansen running past Mount Fuji on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen line. Photo courtesy JR Central.)