Threat Landscape: Corporate Japan Its Own Worst Enemy in the Ransomware War

Economy Society Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

As a leading economic power, Japan is at the forefront of industries ranging from manufacturing to medicine to finance. This makes it a major target for cyberattacks from a host of nefarious actors, but Japanese organizations have been slow to adapt to the growing threats from ransomware and other attacks. Over my 20-plus years working in cybersecurity, I have come to recognize many distinct challenges confront Japan’s traditional companies in forging affective strategies to minimize risk and bolster cyber resilience. Below I look at three cases of cyberattacks that have occurred at Japanese firms in 2024 and consider the core issues at hand.

Cyber Vulnerability: Three Case Studies

Case 1: Lack of Transparency at Major Publisher

In an incident highlighting how poor transparency increases vulnerability, in June 2024 a leading Japanese publishing group was hit by a ransomware attack that caused a systemwide crash, leading to delays in publication deliveries and bringing the organization’s video streaming service to a halt.

What stands out about this case is that the organization held off from disclosing that customer data had been breached for nearly three weeks, an unbelievably long span considering the scale of the attack. While the timing of the announcement was certainly made as part of an overarching cybersecurity strategy, it underscores the importance for companies to balance the timing of public disclosure against the need for transparency.

Compared to their Japanese counterparts, companies in the West are typically subject to strict transparency requirements that demand the swift release of relevant information. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, for instance, requires firms to report data breaches within 72 hours.

Case 2: Prolonged Attack on Regional Supermarket Chain

In February 2024, a ransomware attack crippled the ordering system of a regional supermarket chain. Recovery was slow, taking over two and a half months for the organization to fully restore operations.

The loss of core systems severely impacted the firm’s ability to supply products to outlets and run promotional campaigns. External communications were limited to phone, fax, and postal mail, and payments and refunds to vendors had to be approximated. Fortunately, the company’s point-of-sale system remained online and workaround measures allowed the chain to avoid a total shutdown, but the overall efficiency of store operations took a costly hit.

The case illustrates the difficult, time-consuming process of restoring data following a ransomware attack, with recovery being particularly slow when systems critical for operations have been hit. Japanese companies typically have few measures in place to ensure a quick recovery and business continuity in the wake of a cyberattack.

By contrast, a retail giant in the United States that suffered a similar attack managed to get core systems up and running again within 48 hours by activating offline backups. Working quickly to identify the attack path and patch vulnerabilities, the firm’s cybersecurity team restored over 90% of operations within a week. The swift recovery owes to the company being prepared for an attack, having multiple backup systems in place, and building a rapid response team composed of internal and external experts.

Case 3: A Digital Solutions Firm’s Questionable Response

In May 2024, a ransomware attack at a prominent printing and digital solutions company demonstrated that while progress is being made in Japan’s approach to cybersecurity, challenges remain. The firm, a leader in the industry boasting an impressive list of clients spanning both the private and public sectors, moved to disclose the attack after just three days. It also provided regular updates, illustrating an awareness of the need for transparency, as the incident affected clients like financial institutions and public agencies, organization that are particularly sensitive to cybersecurity issues.

While these steps are laudable, the firm undermined its efforts when it initially announced that it had uncovered no proof that personal data had not been compromised, only to have to retract the statement after evidence surfaced suggesting that a breach had occurred. The case demonstrates the hurdles in gathering and accurately analyzing information during the early stages of a cyberattack.

Outside Japan, leading firms in the same sector, especially those handling sensitive data, often have dedicated security teams and advanced analytical tools at the ready to rapidly assess risks and enable firms to take appropriate actions to prevent or stem leaks of confidential data, ensure timely and accurate communication with clients, and maintain compliance with industry standards.

Issues for Japanese Companies

While progress is being made on the cybersecurity front, the above cases demonstrate key challenges—what I call the “four walls”—confronting Japanese traditional organizations.

First is “the wall of decision-making,” producing slow responses to crisis.

The traditional decision-making process at Japanese companies is well-suited for careful, measured management in normal times. However, it can quickly become a company’s undoing when an emergency like a cyberattack that requires quick, decisive action strikes. An incident at a Japanese manufacturer offers a case in point. Looking to safeguard its systems, the firm decided to fast-track the installation of antimalware software, but spent two weeks approving the move, during which time it was targeted in an attack.

Next is “the wall of cost,” or reluctance to invest appropriately in cybersecurity.

Japanese organizations typically view cybersecurity investment as an overhead cost that does not directly add to profits. An example of this type of thinking can be found in a major Japanese corporation deciding that ¥1 billion was too much to pay for cybersecurity, only for the firm to suffer an attack that cost it triple that amount. In contrast, US companies are more apt to invest heavily in cybersecurity, seeing it as a business enabler and a vital infrastructural investment needed for business growth, rather than merely an overhead cost that must be kept in check.

Third is “the rotation wall,” a human-resource system facet that leads to low cybersecurity expertise.

It is standard practice at Japanese firms to rotate employees every few years, sending them to departments that may be unrelated to their skills and previous experience. This has severely hampered the ability of organizations to build an in-house population of cybersecurity experts. As an example, a Japanese electronics company’s decision to replace the head of its cybersecurity team every two years prevented it from accruing a cadre of employees with a high level of specialized knowledge. IT firms in the United States, on the other hand, often employ CISOs, or chief information security officers, who as senior executives often remain in their posts for a decade or more, developing, implementing, and enforcing the firm’s cybersecurity strategy.

And fourth is “the wall of silence,” creating a culture of hesitancy to disclose information.

The prevailing tendency at Japanese firms when faced with a crisis is to hold back from making an announcement until all the details are known. However, such caution often makes an already bad situation worse. This was the case at one Japanese financial institution that suffered an attack but was slow to respond, allowing a breach of customer data to worsen and in the end costing the organization more than 10 times what it initially estimated it would need to spend to deal with the problem.

Exercising Firm Leadership

Japan’s cybersecurity capabilities have certainly improved, but organizations are far from able to keep pace with rapidly evolving cyber threats. Companies will need time to develop cyber infrastructure on par with leading countries to deal with these challenges, which I believe they can do by leveraging their strengths and adopting best practices from a wide range of sources.

Far from being just an issue for IT teams, cybersecurity today permeates operations at every level of an organization. Central to surmounting these challenges is for executives to take an active role in protecting organizations from online threats. In addressing cybersecurity issue, Japanese traditional companies should focus on five key elements. They must clearly define cybersecurity’s position within wider organizational strategy, optimize resource allocation, integrate risk management across the board, drive cultural transformation within the company, and build trust with stakeholders.

Going forward, company executives need to use their influence to determine an organization’s approach to cybersecurity. Now is the time for bold action.

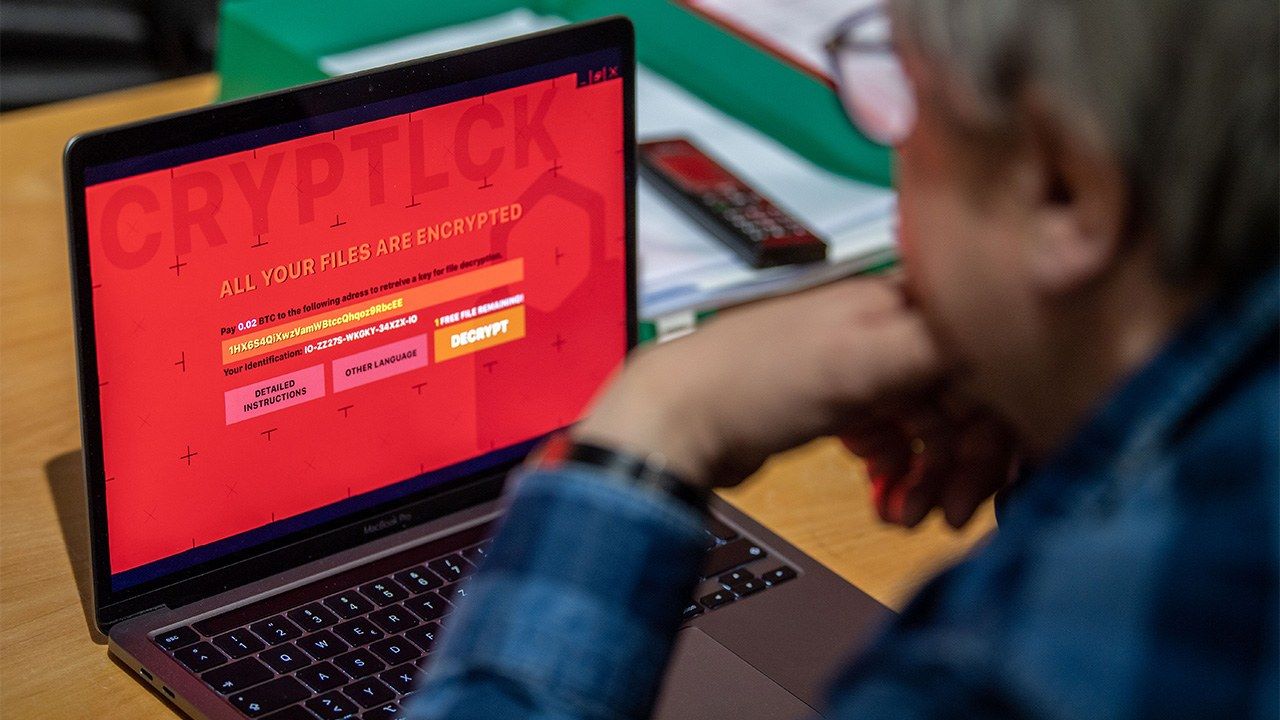

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A computer screen displays a ransomware message. © DPA/PictureAlliance/Reuters.)