Japan Legislates Against the Growing Menace of Customer Harassment

Work Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Confronting Harassment of Customer Service Workers

“Customer harassment,” a term that describes disruptive behavior by customers, has become a major issue in Japan in recent years. Examples of such kasuhara, as it is called in Japanese, include swearing at, or throwing objects at, customer service workers, other forms of violence, unreasonable demands for compensation, persistent complaints, detaining staff for extended periods, forcing staff to get on their hands and knees and apologize, and shaming businesses on social media. These behaviors not only disrupt work environments and create significant physical and emotional stress, but also cost businesses significant time and money. Addressing bullying by customers is therefore a top priority in running a business.

The issue of harassment by customers first came into the spotlight in Japan in 2017 after the publication of the results of a study on maliciously lodged complaints conducted by the major trade union UA Zensen. The study, which found that 70% of the union’s 50,000 members had been on the receiving end of some form of harassment, received extensive media coverage. This led to a series of media reports on customer harassment in different industries, and growing calls to do something about it. (In a study conducted in June 2024 by the distribution and general service divisions of UA Zensen, 46.8% of respondents said that they had been the victim of abusive behavior in the previous two years, down from 56.7% in 2020. The decrease is thought to be the result of public awareness and workplace initiatives.)

The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare was so concerned about the problem that in February 2022 it produced a manual for businesses on dealing with problem customers, and in September 2023 added customer harassment to the admissible grounds for work-related psychological disorders. In December of that year, the government amended the Hotel Business Act to give hoteliers the power to turn away badly behaved guests. In July 2024, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government said that the assembly would debate Japan’s first customer harassment bylaw in September. The central government and ruling coalition are also making moves to legislate.

How Did Things Get So Bad?

Customers and service workers should be on an equal footing. So why has harassment by customers in Japan gotten so bad as to require legislation? There are many complex factors are behind the rise of customer harassment in Japan. Here, I will group them in three categories.

1. “Always Right” Entitled Consumers

Many Japanese corporations have always made “putting the consumer first,” or assuming that the “customer is always right,” part of their guiding philosophy. The end of Japan’s rapid economic growth period gave rise to the idea that to outperform their rivals, businesses had to see things from the customer’s perspective. The Product Liability Act, which entered force in 1995, and the amendment of the Basic Act on Consumer Policies (formerly the Basic Act on Consumer Protection) in 2004, followed by the creation of the Consumer Affairs Agency in 2009, showed the progressive enactment of steps toward consumer protection and independence.

At the time that the Act on Consumer Protection was first enacted in 1968, consumers’ relative lack of knowledge and influence put them in a disadvantageous position. However, as Japanese society as a whole became more consumer-oriented, the tables were turned, giving some consumers an unconscious bias that has caused them to expect to be treated like gods, as well as having certain expectations of staff.

2. Better Service Sparks Unreasonable Expectations

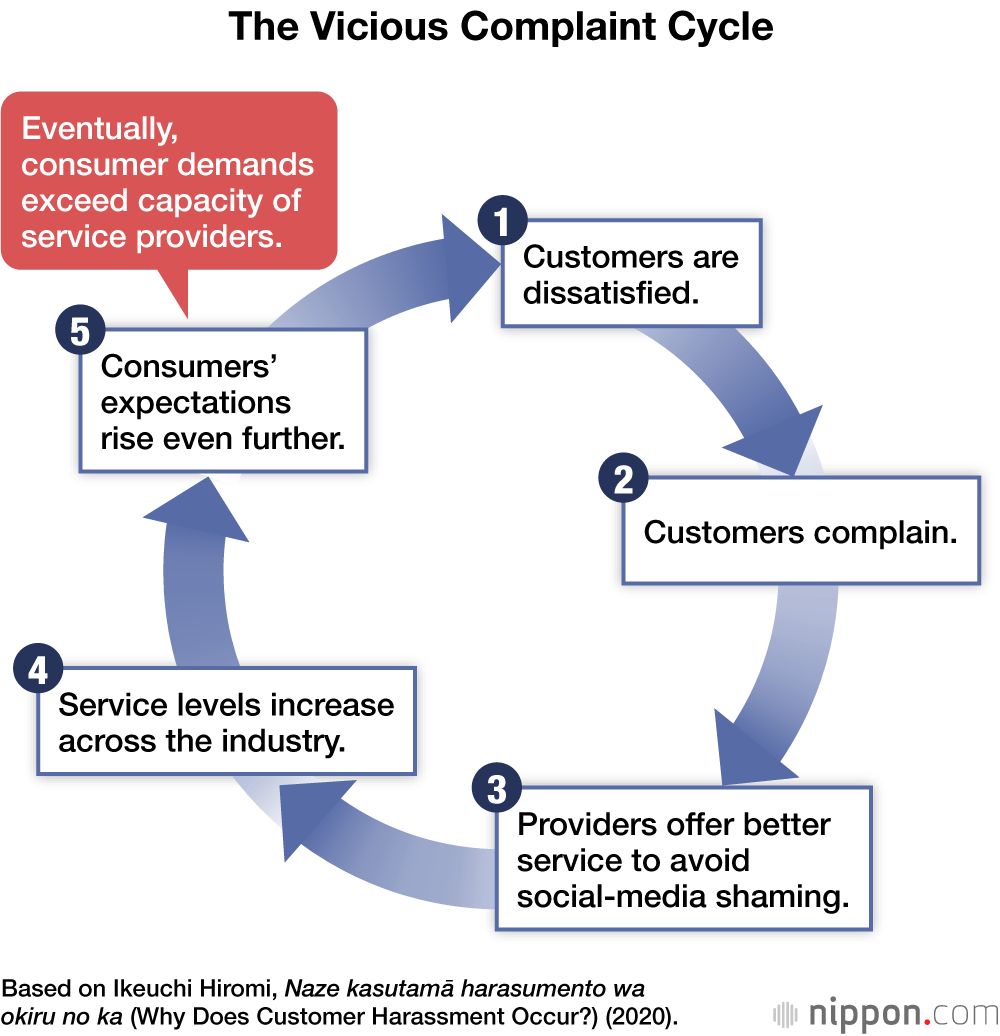

Japan’s service culture, which has its roots in the spirit of hospitality and is characterized by high levels of service, is responsible for high levels of customer satisfaction, while simultaneously being a cause of complaints. We can define the mechanism behind this phenomenon, with reference to the changing media environment, as follows:

First, a customer becomes dissatisfied for some reason. The customer’s dissatisfaction next manifests as a complaint. Because there is now a possibility that the customer will immediately post about the issue on social media, placing the complaint before a broader audience, the business offers even better service to meet the consumer’s demand. It follows naturally that when one business begins offering higher levels of service, others are forced to follow, giving rise to exceptionally high levels of service across the industry. In the end, this results in even greater demands from consumers, eventually making it impossible to provide service that exceeds expectations—spawning renewed dissatisfaction and taking us back to the first step in the “vicious complaint cycle.”

3. Fatigue and Stress Give Rise to Intolerance

Many Japanese currently experience significant stress related to interpersonal relationships and work. Stress reduces concentration and judgment, and causes people to lose emotional control. As more people descend into uncontrollable anger, a culture of intolerance arises in society as a whole, and people become unforgiving of the slightest error. My own surveys suggest that there has been an increase in harassment of service workers, triggered by small things like the way staff hand customers their change or bag their purchases.

Ensuring Effective Legislation

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, the Japanese government has passed legislation in an effort to combat harassment of customer-service workers. In 2019, the Labor Ministry amended a workers’-rights law to force employers to take steps to prevent workplace bullying (the amended law is commonly referred to as the “Power Harassment Prevention Act”), and it has been reported that further amendments are on the way to address customer harassment. In June 2024, the government included a reference in its Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform to “doing more to counter this issue with a view to implementing legislative measures,” and in July, the Labor Ministry indicated that it would adopt a policy of obliging businesses to protect employees from harassment by customers. An amendment is on track to be tabled during the 2025 ordinary Diet session at the earliest.

With legislation, however, come several challenges. The biggest is defining “customer harassment”—that is, defining the criteria for determining what constitutes an “unreasonable request.” While the amended Hotel Business Act already allows hoteliers to turn away prospective guests, it is unclear what criteria need to be met, and many hoteliers have yet to implement the measures spelled out in the new law. To make customer harassment legislation effective, there is a need to clearly define what constitutes “customer harassment,” so businesses are not forced to make judgment calls.

The creation of a work environment that allows employees to work with peace of mind is also essential in order to prevent harassment. Because employers that fail to provide such an environment could be charged with neglect of duty or breach of employer liability, the guidelines need to detail the specific measures that businesses should take. Such steps might include issuing a manual for dealing with disruptive customers, establishing a dedicated helpline, or offering more staff training. While the guidelines do call for explicitly setting out categories and examples of harassment, because this differs significantly depending on the type of service being provided, it is desirable for individual companies (and, ideally, individual industries and sectors) to draw up guidelines appropriate to their own operations.

What is most important is that the legislation actually functions in the situations it is designed for, rather than becoming just another toothless law. To this end, it is essential that employers do not merely implement a policy, but also publicize it, so that each and every employee fully understands it. This will create a corporate culture that ensures that employees who complain of harassment are not psychologically or mentally isolated.

Unlike workplace bullying, customer harassment is caused by external actors, making it more difficult for companies to prevent or deal with. If we are serious about eradicating customer harassment, there is a need for consumers to change their attitudes too. Of course, we also need to ensure that the legislation will not make it more difficult for consumers to speak out.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)