Making Japan a Country of Choice for Foreign Workers

Politics Society Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Technical Trainees and Specified Skilled Workers

The number of foreign migrants working in Japan has surged over the past decade, reaching more than 2 million, according to the latest figures from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (October 2023). Legislation passed by the Diet last June will revamp the two main programs under which foreign nationals are permitted to work in lower-skilled and semiskilled jobs in Japan: the Technical Intern Training Program and, secondarily, the Specified Skilled Worker system. In the following, I explain the reforms to be implemented over the next three years and discuss additional changes that will be needed to meet the government’s stated goal of competing successfully for global human resources.

The TITP accounts for the largest number of foreigners legally working in Japan today, about 410,000 at last count. The program brings foreign nationals to Japan as paid interns, mostly in lower-skilled jobs, with the expectation that they will return home within five years. TITP trainees make up a significant component of the workforce at many small and medium-sized manufacturers, farming and fishery operations, construction operations, and nursing care providers, particularly outside Japan’s major urban areas.

The SSW category, meanwhile, is a relatively new status of residence instituted in April 2019. Reserved for foreign nationals equipped with a certain level of job skills and Japanese language proficiency, it was designed to address Japan’s growing labor shortages by providing a source of semiskilled, workforce-ready foreign labor. The program stalled when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, but after growing by a robust 75% in 2023, it now accounts for roughly 140,000 workers. Some 70% of those are TITP graduates.

The legislation passed in June is targeted primarily at the TITP, which has come under intense criticism in recent years. Since its establishment in 1993, the TITP has supported many young people from around Asia while providing them with an opportunity to acquire skills that they can take home to aid their countries’ development. While the system has had a measure of success, it has become a target of criticism from the standpoint of labor rights. Charging that the program has veered sharply from its original purpose of contributing to international development, domestic and foreign critics have called attention to exorbitant fees charged by some overseas labor brokers, tight restrictions on job changes, and cases of human rights violations by employers. The legislation passed in June will dismantle the embattled TITP while phasing in in a new system, tentatively called the training and employment (ikusei shūrō) program, by 2027.

Opening the Door to Immigrant Labor

What, then, are the key reforms introduced by the recently passed legislation?

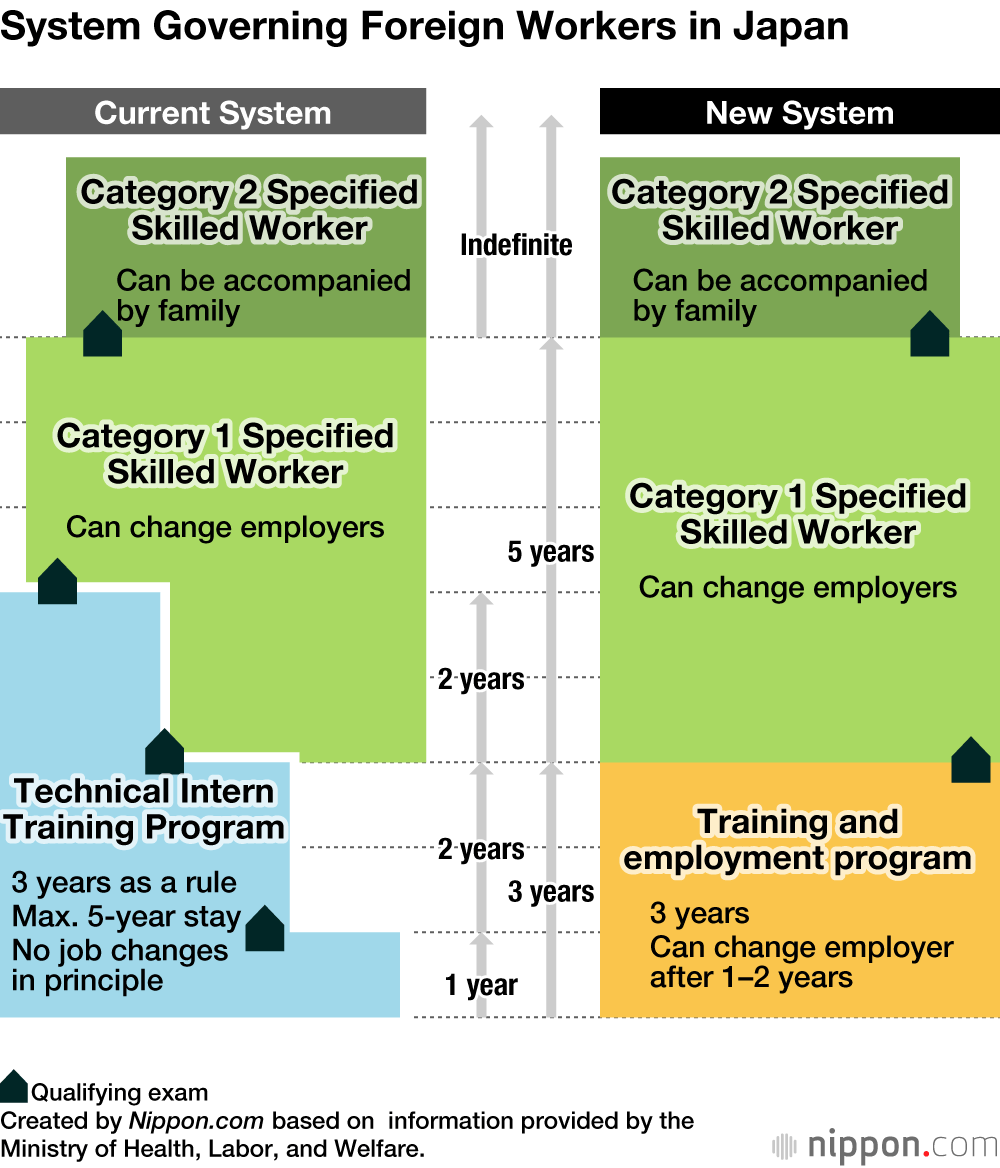

First, the new system is explicitly aimed at securing and developing human resources through the employment of foreign workers. While the stated aim of the TITP was transferring skills to contribute to the economic development of other countries, the training and employment program is about securing and fostering human resources needed in Japan. Although the duration of stay under the new status of residence is limited to three years in principle, the program is conceived as training for the next step up, the status of Category 1 Specified Skilled Worker (SSW 1). SSW 1 permit holders in turn can upgrade to SSW 2, under which they may continue working in Japan over the long term, accompanied by family members, with the possibility of securing permanent residence.

Second, the new system broadens the occupational scope for long-term career building. Some TTIP trainees have been unable to transition to SSW status because they are not working in any of the designated SSW job categories. The new system will do away with this disconnect between the two programs.

Third, the training and employment program enhances workers’ rights. It broadens and clarifies the conditions under which workers in training can switch employers, and it calls for greater flexibility in the processing of transfer requests. Foreign workers are relatively vulnerable to human rights abuses, and facilitating their transfer to a different place of work when the situation warrants it—as in cases of workplace violence—is one of the most important things we can do to protect them.

In addition, after working one to two years (depending on the industry), trainees who pass a basic skills and language examination will be free to switch to a different employer in the same industry for any reason, provided the new workplace meets the program’s criteria. Such transfers will be managed by the Organization for Training and Employment (the tentative name of the agency replacing the Organization for Technical Intern Training). Under that entity’s guidance, supervising organizations (see below), government-operated employment service centers, and other not-for-profit agencies will partner to provide assistance to workers moving between employers. Policy makers are also considering requiring the new employer to provide appropriate compensation to the business from which the worker is transferring.

For the time being, private placement firms will be barred from arranging such transfers. In addition, to deter unscrupulous job brokers, the maximum penalty for encouraging or enabling a foreign migrant to engage in illegal work has been increased from three years imprisonment or a fine of ¥3 million to five years or ¥5 million.

Strengthening Oversight

Fourth, a foreign national’s acceptance and placement under the training and employment program will hinge on the approval of an individual “training and employment plan” (replacing the current TITP). To be approved, the plan must meet a variety of criteria pertaining to the employer’s business, goals for the development of occupational and language skills, and the mode and content of such training. A new plan must be submitted for any proposed change in employer, and each application will be screened to ensure the suitability of the new workplace.

Fifth, the new system will replace the “supervising organizations” of the TITP with “supervision and support organizations.” The TITP’s supervising organizations are nonprofit entities charged with supporting trainees and overseeing participating employers, but they generally have ties to business, and critics have questioned their independence and neutrality, as well as the adequacy of their staffing. To be licensed to operate under the new system, these entities will need to appoint auditors and hire staff commensurate with the number of businesses they oversee. The revised law further stipulates that organizations that fail to perform their function adequately will be shut down, suggesting that they will be subject to periodic reviews and inspections.

The sixth reform addresses concerns about abuses occurring in the sending countries. Under the new system, trainees will be accepted only from countries with which Japan has concluded bilateral agreements known as memorandums of understanding. In addition, the revised law promises to bar participation by unscrupulous overseas brokers, or “sending organizations,” improve the transparency of recruitment charges, and implement guidelines to that any fees charged are reasonable and in line with standards.

Comparison of TITP and Training and Employment Program

Technical Intern Training Program

| Stated purpose | Contributing to overseas development through transfer of skills |

| Duration | Must return home after 5 years as a rule |

| Type of work | Includes job categories ineligible for SSW status |

| Oversight and support | “Supervising organizations” may be poorly staffed and acting in the interests of employers |

| Fees charged by sending organizations | May be unreasonably high |

| Japanese language requirement | None as a rule (N4 proficiency required for nursing care) |

Training and employment program (new)

| Stated purpose | Securing and developing human resources |

| Duration | 3 years as a rule, but system envisions transition to workforce-ready SSW status, permitting long-term employment in Japan |

| Type of work | Same categories as specified by SSW, in principle, to facilitate smooth transition |

| Oversight and support | “Supervision and support organizations” required to appoint auditors, preserve independence and neutrality, and maintain staffing commensurate with number of employers |

| Fees charged by sending organizations | Reasonable brokerage fee a requirement for acceptance |

| Japanese language requirement | Basic proficiency (N5/A1) or equivalent coursework completed |

Created by Nippon.com based on information provided by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Will Mobility Hurt the Regions?

A major focus of the debate surrounding the recent immigration reforms was how to balance foreign workers’ freedom to choose their place of work against the need to retain human resources. Workers admitted under the training and employment program will be permitted to change employers at their own discretion after one to two years (depending on the industry), providing they can demonstrate a certain level of competence and Japanese language proficiency. Now companies and communities are facing the question of how to retain the foreign labor they secure under the new system.

Their fears are not unfounded. According to a survey of SSW permit holders compiled by the Immigration Services Agency, of those that transitioned from the TITP, a full 39% relocated to a different prefecture within a month of obtaining SSW status. The outcome of this movement, as expected, was a shift toward the urbanized, industrial areas around Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya. The Kantō and Kansai regions and Aichi Prefecture experienced a net influx of foreign workers, while Hokkaidō and every prefecture in the Tōhoku, Chūgoku, and Kyūshū regions suffered a net loss.

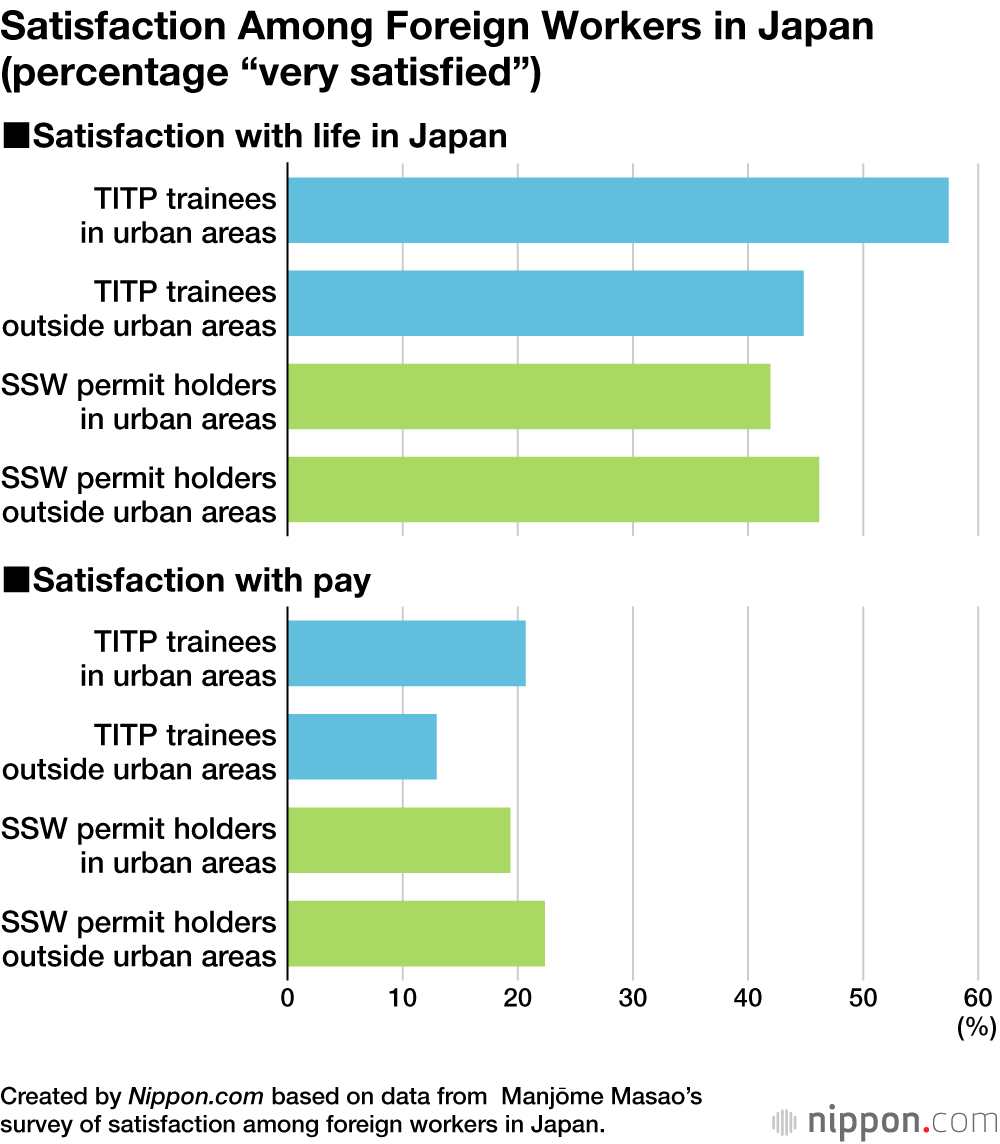

However, the results of my research team’s survey of foreign workers (conducted from October 2022 to March 2023) suggest that this urban migration may not always pay off for the workers. Among TITP trainees (who are generally not permitted to move around), respondents living in major urban areas were more likely to pronounce themselves “very satisfied” with their pay and life in general. But among SSW permit holders, satisfaction was higher among respondents outside those urban areas. This suggests that foreign workers with the opportunity to move around may see the advantages of less urbanized parts of Japan, including the relatively low cost of living, better local governmental support, and closer interpersonal relations in smaller communities.

Our survey also found that respondents’ satisfaction with their daily life and work bore a strong correlation to Japanese language proficiency, regardless of the time spent in country.

Explaining the recent reforms, the government has stated that it wants to make Japan a “country of choice” for foreign talent over the medium to long term amid intensifying international competition over human resources. Of course, this means not just opening the door to immigrant labor but also making Japan a place where talented foreign nationals want to live and work. What should firms and communities do to attract and retain international talent? The results of our survey suggest that assistance with everyday life and Japanese language education are among the most important measures we can take.

In more basic terms, quality of life is essential to retaining foreign employees. In addition to providing sufficient time off and leisure opportunities, we must create multicultural workplaces and communities where foreign nationals can play an active role, side by side with their Japanese counterparts.

Next Steps: Career Development and Inclusion

Another key to employee retention is appropriate training and career development.

Of the foreign workers responding to our survey, 97% had come to Japan with clear, concrete objectives in mind. In order of frequency, these were acquiring skills or technical know-how, earning money for their families back home, and learning Japanese. What this tells us is that job and Japanese language skills rank right up there with sending money home from the perspective of these workers.

Our survey also highlights the connection between good relations with one’s supervisor and job satisfaction. Respondents who said that they had received fair and appropriate evaluations from their superiors were more likely to indicate a high level of job satisfaction. Overall, our results confirm the idea that workers are less apt to find satisfaction in jobs where they have little opportunity for growth and are merely expected to follow orders. Business owners and managers need to assign work to their foreign employees with a view to building skills and boosting motivation. They should familiarize themselves with their foreign workers’ individual aptitudes and career aspirations by discussing these matters with them during their daily interactions.

In short, Japanese companies need to provide personalized support for career development to bolster job satisfaction if they want to attract and retain talented foreign workers under the training and employment and SSW programs. Such efforts, combined with supportive policies at both the national and local levels, will contribute to workers’ overall satisfaction with life, enhance the reputation of individual communities and businesses as good places to live and work, and make Japan an attractive destination for international talent.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)