Xi Jinping European Charm Offensive: Exploiting Cracks in Western Solidarity

Politics World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s May 5–10 tour of France, Serbia, and Hungary was part of a European charm offensive geared to securing a strategic advantage for China in its ongoing battle with the United States for leadership of the international order. The basic aim of this campaign is to draw potential allies closer and sow division among the “enemy ranks,” in the tradition of the external influence operations conducted for decades by the Communist Party of China.

A highlight of the trip was Xi’s state visit to Budapest, where I have lived since the fall of 2023. Xi’s meeting with Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban resulted in a raft of new agreements extending beyond trade and investment to cooperation on law enforcement, border control, and the media. Can Beijing leverage its ties with the Orban regime—a frequent critic of EU policy—to undermine European solidarity? In the following, I offer a brief analysis of Xi’s recent tour with an emphasis on the East European leg, which I had an opportunity to observe from up close.

Xi’s Favored Nations

Why France, Serbia, and Hungary? For some insight into the selection process, let us consider recent revisions to China’s immigration policy. With Xi’s European tour in the offing, the Chinese government began phasing in a 15-day visa-free travel policy for select European countries, beginning in December 2023. China now unilaterally welcomes visa-free short-term visits by passport holders from 11 European countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Ireland, and Hungary—even though it has cited the principle of reciprocity in refusing to reinstate a similar exemption available to Japanese visitors prior to the pandemic.

Excluded from China’s visa exemption are the Nordic countries, which have been increasingly vocal in their criticism of Beijing’s pro-Russia stance since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Also missing from the list of favored nations are Japan and South Korea, key US allies in East Asia, as well as Britain and Canada, which share high-level intelligence with the United States. The selection speaks volumes about Beijing’s diplomatic priorities.

Similarly, Xi’s European itinerary targeted the EU countries deemed most likely to assert their independence from EU and US policy and welcome closer ties with China.

Leveraging France’s “Spirit of Independence”

This year marks the sixtieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and France. At the May 6 state dinner hosted by President Emmanuel Macron and his wife, Xi praised President Charles de Gaulle’s decision to sever formal ties with Taiwan and establish full diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in the face of US opposition. This and other “highlights in China-France interactions,” said Xi, “are all attributed to the spirit of independence, which should be cherished and carried forward.” Against the backdrop of Macron’s calls for European “strategic autonomy,” Xi’s remarks can be taken as a not-so-subtle plug for French independence from US foreign policy.

In his talks with Macron the following day, Xi steered clear of controversy and focused on stepping up dialogue to find a peaceful resolution to the conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine. In the economic realm as well, he emphasized cooperation, especially in regard to AI (artificial intelligence) governance. Even Ambassador to France Lu Shaye, notorious in the West for his advocacy of “wolf-warrior diplomacy,” has refrained from baring his fangs in recent months.

China’s East European Fan Base

The governments of Serbia and Hungary, noted for their own autocratic leanings, are among the most pro-Chinese countries in Eastern and Central Europe. President Aleksandar Vucic of Serbia and Prime Minister Orban of Hungary were the only European leaders (not counting Russian President Vladimir Putin) to participate in the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Forum, held in Beijing in October 2023.

This was Xi’s second trip to Serbia, after an eight-year hiatus. His recent stay in Belgrade was timed to coincide with the anniversary of the notorious bombing of the Chinese embassy in that city (then capital of Yugoslavia) during the intervention by NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) in the Kosovo War. This can be taken as another jab at the United States, which took responsibility and apologized for the incident. President Vucic, who continues to view NATO with deep suspicion, rolled out the red carpet for Xi, adorning the center of Belgrade with Chinese flags and banners welcoming Serbia’s “honored friend.” In front of a cheering crowd, Vucic declared, “We have a clear and simple position regarding Chinese territorial integrity. Yes, Taiwan is China.”

The high-speed rail line China is building between Belgrade and Novi Sad, Serbia’s second-largest city, will be the only 200 kilometer-per-hour train operating in the Balkans. China places great emphasis on the project as a signature achievement of the Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, which has lost momentum as the Chinese economy has slowed.

Partners in Surveillance

The last stop on the tour was Budapest, where Xi received an equally warm welcome. Although Hungary belongs to the EU and NATO, President Orban is known for clashing with other European leaders on policies ranging from immigration to support for Ukraine. This makes Hungary a prime target for influence operations designed to undermine European solidarity.

Xi’s May visit proved fruitful, generating 18 new bilateral agreements. Locally, media attention focused on projects backed by interests close to the government, including nuclear power development and construction of a high-speed rail link between the airport and the center of Budapest. But the expansion of cooperation in non-economic sectors deserves equal attention. The two governments concluded five agreements on cultural cooperation involving the China Film Administration, Xinhua News Agency, China Media Group, and the People’s Daily. Such arrangements could easily be used by the CPC to disseminate propaganda and influence Hungarian public opinion in China’s favor.

The expansion of bilateral cooperation in the areas of policing, surveillance, and security is also cause for concern. Previous agreements opened the way for the use of Chinese-made surveillance cameras and even Chinese police officers on Hungary’s streets. Under the latest spate of agreements, China will be cooperating in the construction of a state-of-the-art checkpoint on the border with Serbia.

Beijing has been pursuing similar arrangements elsewhere in the world, particularly with developing and newly industrializing countries. But the partnership with Budapest is especially worrisome because Hungary is a member of the EU and NATO. The concern is that Chinese involvement in Belgrade’s law-enforcement, media-control, and surveillance efforts could contribute to the erosion of liberal values in the country and the region.

During Xi’s visit, a portion of the roughly 30,000 Chinese nationals living in Hungary coalesced into regiments in the Buda Castle district, where Xi was staying, to welcome their leader. The red-capped, flag-waving volunteers drew media attention for their display, but some of the participants caused a fracas when they forcibly removed Tibetan flags displayed by Hungarian citizens to protest Beijing’s policies.

A Magnet for Chinese FDI

Prominent among Xi’s entourage—which counted in the hundreds—were representatives of Chinese industry. Hungary has become a magnet for direct investment by Chinese corporations, particular in the electric vehicle sector. CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co.), the world’s biggest EV battery manufacturer, and BYD Auto, currently vying with Tesla for the title of top EV maker, are both building plants in Hungary, and more are expected to follow. The EU has slapped new tariffs on Chinese-made EVs on the grounds that government subsidies give China’s automakers an unfair advantage over European manufacturers. The Chinese are hoping to avoid those duties by shifting production of Europe-bound vehicles to Hungary.

According to Mercato Institute for China Studies, a German-based think tank, in 2023 a full 44% of China’s FDI in Europe was concentrated in Hungary—a country with a population of around 9 million and an economy less than one-twentieth the size of Germany’s. Meanwhile, Chinese FDI in the EU has fallen to its lowest level in 10 years (6.8 billion euros in 2023), a trend attributable both to China’s economic slowdown and to a less welcoming environment among Europe’s major economies. The rush to invest in Hungary is all the more striking in this context. Orban’s domestic critics charge that the deals the regime has concluded with China are oriented more to the enrichment of Orban’s inner circle than to the nation’s economic welfare.

Divide and Conquer?

In 2012, Beijing launched the 16+1 initiative (16 Eastern and Central European countries plus China) as a cooperative framework, and for the next 10 years China relied on that framework to bolster its ties with Central and Eastern Europe. But in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Baltic states, led by Lithuania, withdrew over Beijing’s deepening ties with Moscow, and other members curtailed their involvement.

The EU, meanwhile, began prioritizing economic security over trade ties with China, responding to the latter’s expansionist posture and belligerent “wolf warrior diplomacy,” as well as to the growing animosity between Beijing and Washington. The romance that had blossomed during the European debt crisis was over.

Cognizant of these changes, China shifted gears from a multilateral approach to individual engagement targeting receptive countries—of which Hungary is a prime example. Beijing doubtless hopes that it can use Orban’s government to influence EU policy, much as it has used the pro-Chinese Cambodian regime to block statements by the Association of Southeast Asia Nations criticizing China’s behavior in the South China Sea.

How far Beijing can take this divide-and-conquer strategy remains to be seen, but the situation bears watching. Despite its recent slowdown, China remains the world’s second-largest economy, and many of its businesses—especially those in the EV industry—are expanding and eager to invest overseas. France, Italy, and Spain are all vying to attract investment in the EV sector. Germany continues to value China as a business partner. Chancellor Olaf Scholz made his second visit to Beijing last April, shortly before Xi’s European tour. Representatives of the German auto industry, which has major investments in China, were critical of the EU’s investigation into EV subsidies, fearing a backlash from the Chinese government. China’s economic clout—which was always the hard power behind its “charm offensive”—remains a powerful inducement for many European stakeholders.

Implications for Asian Security

Beijing has already prevailed on Budapest and Belgrade to take China’s side in EU deliberations targeting the Taiwan problem and China’s maritime expansion in the South China Sea—issues that Xi has identified as vital to China’s “core interests.” China will doubtless apply similar pressure to other European governments going forward. The EU is geographically removed from East Asia, and it has its hands full with the war in Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East, a region with which it has complex historical ties. Within the EU, rapid gains by far-right parties in France and elsewhere—vividly apparent in the results of the June European Parliament elections—are posing a threat to unity and political stability.

Amid such turmoil, President Macron finds himself in a precarious position, and Orban’s political adversaries are in hot pursuit as well. But Beijing is likely to pursue the same brand of economic statecraft irrespective of the ideology of the party in power. Europe, for its part, will continue to vacillate, however subtly, as it weighs the security risks of closer ties with China against the economic benefits.

Japan, for its part, must persuade the EU to sustain an interest in East Asia’s security environment, which is of such vital importance to this country. To counter China’s influence operations, we must strengthen our ties to Europe with the help of accurate and detailed information—including analysis of individual countries’ domestic affairs—and good communication. We lobby persistently to ensure that the Europeans share our concerns regarding China’s behavior and intentions in East Asia. Needless to say, all this assumes that we in Japan fully grasp Beijing’s modus operandi, even as we leave the door open to constructive dialogue with our powerful neighbor.

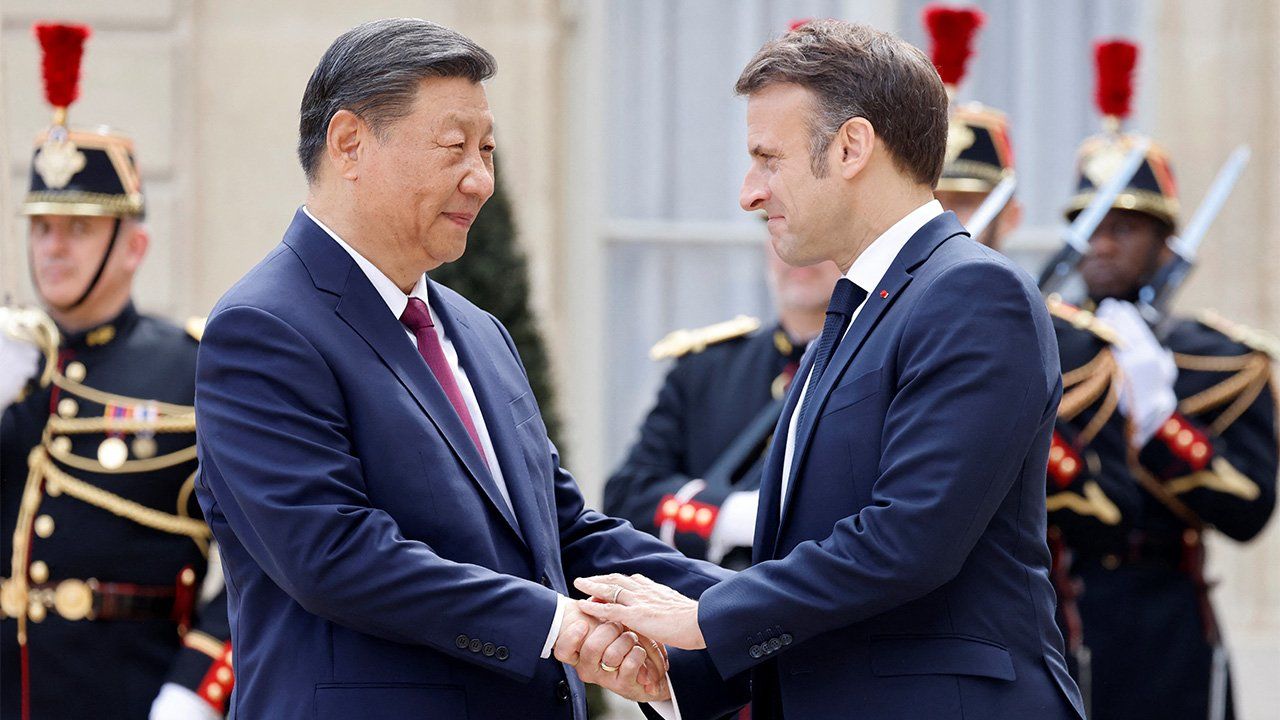

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: President of France Emmanuel Macron welcomes Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Elysée Palace in Paris, May 6, 2024. © AFP/Jiji.)