Understanding Japanese Unionism: The Shuntō System in Context

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Each year, as part of the annual Group of Seven agenda, representatives of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (JTUC-RENGO, or Rengō) meet with labor leaders from other national trade union centers (including America’s AFL-CIO, Germany’s DGB, and Britain’s TUC), along with representatives of the International Trade Union Confederation and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The Labor 7, as this group is known, prepares recommendations for the G7 leaders and presents them to the head of state chairing the upcoming summit.

Gōno Akiko, Rengō’s international representative, became the first Japanese president of the ITUC in 2022.

Rengō President Yoshino Tomoko presents Prime Minister Kishida Fumio with a statement by the L7 group of labor leaders at the Prime Minister’s Official Residence on April 7, 2023, in advance of the G7 Hiroshima Summit. (© Jiji)

Japan’s labor organizations occupy an important place in the global labor movement. However, organized labor in this country differs in key respects from unionism in the West, reflecting Japan’s own distinctive culture, history, and social structure. The annual “spring wage offensive,” or shuntō, is an important product of this unique historical development, as I explain below.

Unionization in Global Decline

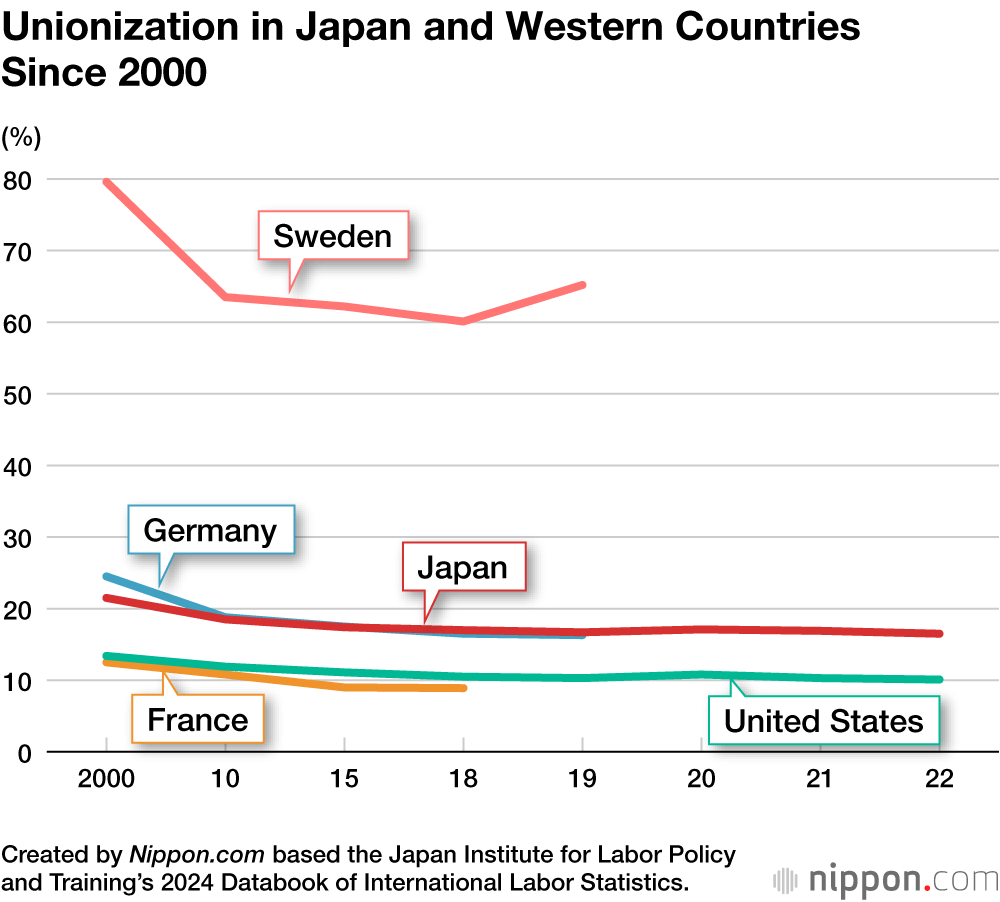

As charted in the accompanying figure, unionization has declined around the world since the beginning of the twenty-first century. (A notable exception is South Korea, where union membership has been on the rise, hitting 14.2% in 2021.) The Nordic countries, led by Sweden, still boast a relatively high rate of unionization, but in Germany and Japan, membership has dropped below 20%. Only about one in ten US employees belongs to a union, and in France the figure is even lower.

Numbers do not tell the whole story, however. In France, as in other European countries, organized labor has contributed greatly to overall improvements in labor conditions, even though the rate of membership is relatively low. Under French labor law, the sectoral agreements that industry-based unions conclude with employers’ associations extend to all workers in the sector, whether or not they are union members. As a result, more than 90% of French employees are covered by collective labor agreements. Germany’s labor laws are somewhat different, but the extension of labor agreements is still fairly frequent, with the result that more than 50% of German employees were covered by company- or industry-level collective agreements as of 2021. Throughout Europe, the efforts of labor unions have had a massive impact on working conditions and society as a whole.

The extension of collective labor agreements is much less common in Japan than in Europe. The biggest reason is that company-based enterprise unions, concentrated in Japan’s major corporations, are the primary type of labor organization. While many of these unions belong to industry-wide federations, the negotiation of collective labor agreements generally takes place at the company level, without the federation’s direct intervention, and in the vast majority of cases, the terms cover only the members of the union that concluded the agreement. As a result, the percentage of Japanese workers covered by union-negotiated agreements is estimated at less than 15%.

From this perspective, there is no denying that individual Japanese trade unions are comparatively weak when judged by their power to influence overall labor conditions and, by extension, to shape social norms. But the Japanese labor movement has developed its own unique system for strengthening worker solidarity.

Capsule History of Japanese Labor

The world’s first trade unions emerged in mid-eighteenth-century Britain, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. Similarly, the first Japanese labor unions emerged in the 1890s, a period of rapid industrialization in Japan.

Japan’s earliest trade unions were organized by workplace. Although the leaders of the labor movement were eager to consolidate these disparate organizations and unite the nation’s workers by industry or occupation, their efforts foundered in the face of stiff opposition from employers, backed by anti-union government policies, as embodied in the Public Order and Police Law of 1900 and the Peace Preservation Law of 1925. In 1940, under the government’s general wartime mobilization, the labor unions were disbanded and absorbed into a government-sponsored workers’ organization, bringing this chapter in Japan’s labor movement to a close.

A new chapter began immediately after World War II, however, thanks to the Trade Union Law of 1945, the 1947 Constitution (which guaranteed the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively), and the early union-friendly policies of the US Occupation. Local unions proliferated rapidly, and by 1949, a full 55.8% of the labor force was unionized.

Unlike today’s company-wide unions, the first labor organizations of the immediate postwar period were organized by workplace. It was not long, however, before the workplace unions affiliated with a particular company formed company-wide associations, which then coalesced into enterprise unions of the sort that we see today.

Why have these enterprise unions—as opposed to more broad-based sectoral- or occupation-based organizations—continued as the primary actors in Japan’s labor movement? This question has been the subject of a good deal of research, and a number of competing theories have been advanced. The biggest reason, however, is doubtless that the unions themselves preferred to organize and function on a company-by-company basis.

Uniting Blue- and White-Collar Workers

One way in which Japan’s postwar enterprise unions differ from their prewar counterparts is in their inclusion of white-collar workers. The enterprise unions of postwar Japan are “mixed occupation unions” that make no distinction between a company’s factory workers (for example) and its office staff. Labor historians have explained this as a deliberate policy by union leaders to use the structure of their organizations to address the unequal status and treatment of blue-collar and white-collar workers. The inclusion of manual laborers and management-track employees in the same labor organization constitutes a key difference between Japanese labor unions and the industry- or trade-based unions of the West.

Since the members of a particular Japanese enterprise union are by definition employees of the same company (most often for life), union membership confers a dual identity, and this dual nature extends to the union as a whole. The unions’ primary purpose is to strengthen worker solidarity, but they are also predisposed to cooperate with management to support the competitiveness of the company that provides the workers with employment. From the standpoint of organized labor’s primary purpose, the unions need to welcome and encourage membership by nonregular workers, and they must be wary of placing too much weight on their corporate identity.

Evolution of the Shuntō

In the aftermath of World War II, Japan’s labor leaders sought to unify and expand the labor movement with a view to boosting the bargaining power of Japan’s workers. Two nationwide umbrella organizations were formally launched in 1946. Meanwhile, enterprise unions in the same industrial sector (such as metals) began to form loose councils, which developed into stronger industry-based labor federations. These federations became the dominant form of sector-based labor organization in Japan.

The aim of these federations was to form a united industry-wide front to fight for higher wages and better working conditions. Because enterprise unions alone retained the right to strike, this “unified struggle” involved coordinating the timing of the member unions’ annual negotiations, their wage demands, and their criteria for accepting or rejecting their management’s counter-offer.

This coordinated approach produced a synergy that made it possible to secure uniform conditions for unionized employees at all the major firms in a given industry, including companies that had performed poorly that year. In addition, it created a kind of “wage-increase market” whose ripple effect extended to smaller, non-unionized companies. The benefits have been wide-ranging, extending beyond wage increases to shorter working hours, new forms of employment, better retirement benefits, and later mandatory retirement. In this way, Japan’s labor federations have performed a function similar to that of the industrial unions of the West.

The effort to merge these sector-wide labor offensives into a single unified campaign gave birth to Japan’s shuntō, dating back to around 1955. Although the focus tends to be on wage increases, the shuntō is also an opportunity for workers and management to trade views on a wide range of issues, including business strategy and management policies.

The Role of Rengō

In 1989, four nationwide labor organizations (the General Council of Trade Unions of Japan, the Japanese Confederation of Labor, the Federation of Independent Unions, and the National Federation of Industrial Organizations) merged to form the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, or Rengō. Since then, Rengō has played a leading role, along with various industry-based unions, in the annual coordinated effort by Japan’s enterprise unions to boost wages and improve labor conditions.

During that time, the Japanese economy has faced daunting challenges. The collapse of the asset bubble in 1992, which ushered in a long period of stagnation and deflation, along with such crises as the Great Recession of 2008, forced the unions to choose between higher wages and job stability. But things have begun to look up. With consumer prices surging and corporate profits on the rise, the companies participating in the 2024 shuntō negotiations granted their employees a combined wage increase (including scheduled annual increases along with base pay) of more than 5% for the first time in 33 years. The unions have also made significant progress securing pay raises for the growing ranks of nonregular employees.

For labor unions around Japan, there are few events of greater importance than the shuntō, a uniquely Japanese institution. As a longtime participant in this nationwide movement, I hope and trust that future spring labor offensives will lead to further improvements in working conditions, job satisfaction, and living standards for workers around Japan, regardless of their form of employment.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ahead of the 2024 spring wage offensive, national and local labor leaders affirm their solidarity at a Rengō (Japanese Trade Union Confederation) rally on March 1. © Jiji.)