Streaming Puts J-Pop Back in the Spotlight: Yoasobi and Gacha Pop

Culture Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Ranking Imbalance

The Japanese pop duo Yoasobi are at the frontline of a new wave of domestic artists gaining attention abroad. According to data analytics platform Chartmetric, which daily tracks streaming, social media, and live performance of 10 million artists worldwide, they rank steadily among the top 400 to 600 performers, putting them on par with such acts as the all-girl K-Pop group Le Sserafim.

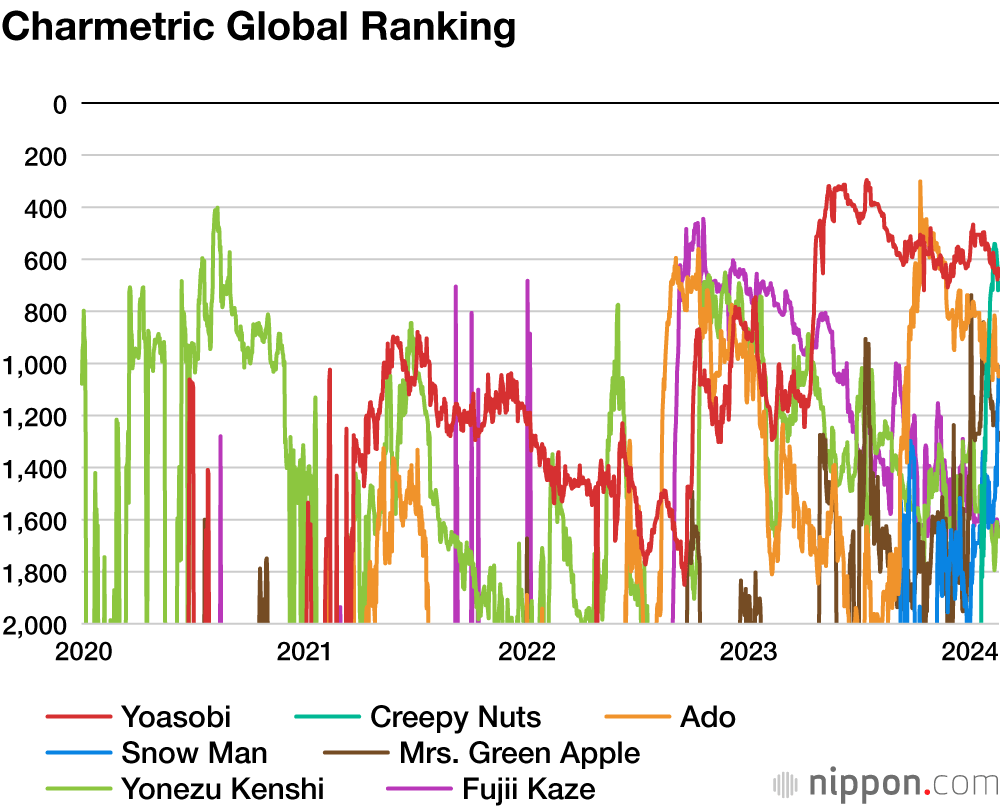

The highest-ranked Japanese musician at the start of the decade, right as the COVID-19 pandemic was heating up, was Yonezu Kenshi, who reached 402nd on August 11, 2020, following his appearance in a virtual live concert for the hugely popular video game Fortnite. Yoasobi raced up the rankings in 2021 and 2022, setting a new record for a Japanese act by reaching 296th (July 15, 2023) after the release of their track “Idol” in April 2023.

Yoasobi vocalist Ikuta Lilas, who goes by the moniker Ikura (left), and composer and producer Ayase. (© The Orchard Japan)

Other Japanese performers who have appeared in the upper echelons of Chartmetric’s rankings are singer Ado, who made it to 301 (October 11, 2023) thanks to her hit single “Show,” and hip hop duo Creepy Nuts, who reached 541 (February 10, 2024) with “Bling-Bang-Bang-Born.”

Yoasobi have remained the most listened-to Japanese artists around the world since 2023. But the duo’s global popularity is not mirrored by the Japanese domestic market. They ranked eighth on Japanese music industry giant Oricon’s 2023 list of best-selling artists with ¥5.7 billion in sales. While the group did manage to come in first in digital sales at ¥4.6 billion, this was eclipsed in the overall rankings by top-selling group King & Prince, who pulled in ¥21.8 billion. They also trailed idol group Nogizaka46, placing seventh at ¥6.0 billion. In stark contrast, Nogizaka46 tracks between 5,000 and 10,000 on Chartmetric, while King & Prince, whose music is not even on the streaming service Spotify, are unranked.

In Japan’s music market, there is a three-to-one ratio of CD sales to music streaming, which is opposite the one-to-four ratio of the global market, dominated by North America. This suggests that a performer’s sales and ranking will differ dramatically depending on the marketing method adopted. The conventional approach in Japan has focused on CD sales, as was typical of artists managed by the talent agency Johnny & Associates (now Starto Entertainment). The so-called Sakamichi idol groups that include Nogizaka46 have followed the same marketing strategy of pushing physical media, and it is no surprise that these artists top CD sales in Japan. Musicians like Yoasobi and Ado, on the other hand, have made their songs more accessible to overseas audiences by focusing on streaming and other online distribution.

Vanguard of Alternative Pop

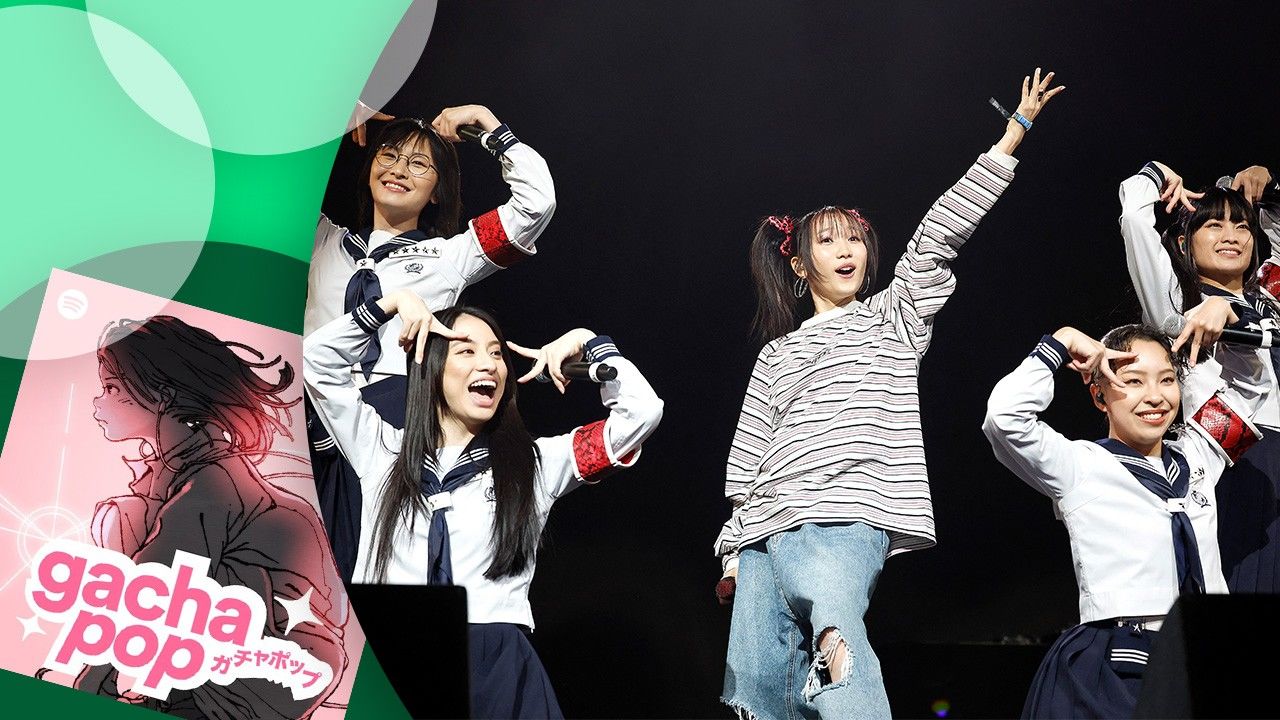

In May 2023, Spotify, the world’s leading music streaming platform, launched its Gacha Pop playlist as a means to introduce fresh Japanese pop culture and music to a wider audience. The playlist, whose description reads “What pops out!? Roll the gacha and find your Neo J-Pop treasure,” features artists including Yoasobi, Ado, imase, Yonezu Kenshi, Fujii Kaze, and Atarashii Gakko.

Gacha is an onomatopoeic word describing vending machines that randomly dispense capsules containing toys and other novelty items. In a similar vein, Gacha Pop offers a mixed selection of Japanese pop music, with its launch signaling the growing influence of J-Pop abroad.

The musicians featured on Gacha Pop are in an entirely different category from the performers who dominated Japanese pop music in the 2010s, idol groups like AKB48 and boy bands managed by Johnny’s or LDH, whose members were regular fixtures on television and who raked in sales with CDs and live concerts.

The shift started with Hatsune Miku, a “virtual” pop star created using Vocaloid voice synthesizing software. Debuting in 2007, she inspired a wave of Vocaloid producers who created music with the software and posted their creations on YouTube and the Japanese video-sharing service Niconico. Among the top stars of the genre is Yonezu Kenshi. A Vocaloid producer since the late 2000s, he signed with Sony Music Records (a label of Sony Music Entertainment) in 2016 and gained public attention with his 2018 hit “Lemon.”

Ayase, who composes, arranges, and produces Yoasobi’s music, also started out as a Vocaloid producer. He formed the duo together with Ikuta Lilas in October 2019, with the group releasing their single “Racing into the Night” through SME that December. Ado was a singer on Niconico covering Vocaloid tracks, and her vocal prowess caught the attention of Universal Music, which released her debut single. Fujii Kaze and Imase, while not Vocaloid producers, also came into the spotlight through social media and online video-sharing platforms.

Unlike conventional Japanese idols, these artists have managed to grab global attention without signing with influential talent management agencies. Their debut songs were not bolstered by television commercial or teledrama tie-ins, nor did they have support from renowned producers. They instead began by simply sharing the unique content they were creating online, eventually attracting fans and becoming recognized as artists through word-of-mouth. A growing number of such “semiprofessional” musicians have subsequently been picked up by agencies and record companies. Some are even starting to outshine mainstream artists.

The Chartmetric ranking below shows the emergence since 2020 of Yonezu Kenshi, Yoasobi, and Fujii Kaze, followed by the entry of conventional artists such as Snow Man and Mrs. Green Apple into the top 1,000.

The impact of streaming platforms for artists who started out small is evident. At the same time, COVID-19 pandemic put a stop to live concerts, causing mainstream artists in Japan to turn their attention to streaming.

Defying Global Trends

There are other factors that make Japan’s music industry an outlier. Sales from streaming and downloads overtook CDs and other physical formats as early as 2011 in the United States and globally by 2015. In South Korea, retail CD sales collapsed even earlier, in 2003. Even as streaming now accounts for over 80% of the global music market, in Japan, CD sales are still higher than digital formats.

The situation can be traced to government regulations to ensure the stability of prices as well as special industry arrangements that keep the cost of CDs high. In addition, talent agencies have nurtured a market strategy aimed at middle-aged and older adults, relying on special incentives to entice ardent fans to buy multiple copies of their favorite artists’ CDs. These and other factors have produced a unique music ecosystem that has defied global trends in another tragicomic example of what in Japan is called “Galápagos syndrome,” a term that describes a product developing in a way that isolates it from global market trends. In Japan’s peculiar environment, there is little incentive for artists to aim for the wider global market.

One sign that the situation was changing was the appearance of Gacha Pop on Spotify. By highlighting a host of original artists from Japan, it has continued to garner new subscribers, a shift that has been bolstered by the concurrent boom in online distribution of anime.

Interpreting the World of Anime

Two clear examples of the music-anime connection are Yoasobi’s “Idol” and “Bling-Bang-Bang-Born” by Creepy Nuts. The former featured as the opening theme for the 2023 hit series Oshi no ko and the latter was the theme song for the second season of Mashle: Magic and Muscles. The tunes provided fresh interpretations and expanded the world of each anime. What is more, that the songs became hits stands as testament to anime’s acceptance as a mainstream form of entertainment.

Cover image for Yoasobi’s “Idol.” (Courtesy RecoChoku Co. Ltd.)

In the case of “Idol,” the lyrics foreshadow the development of Oshi no ko from the manga on which it was based. The music is a separate entity from the main story, but at the same time it provides background context for the work.

However, the song represents more than just a marketing tie-up. There have been many collaborations between musicians and anime that never gained the same level of attention. Just because an anime is successful does not guarantee popularity for the songs on its music track, and vice versa. But when there is synergy between the related but different perspectives of anime and music, it can kindle fervent admiration among fans.

Resonance Throughout Asia

Not all of the songs on Gacha Pop are from anime, of course. Fujii Kaze and Imase have no connection to the genre. Rather, their meteoric rise came after they were sampled by K-Pop stars who were attracted by the novelty of their music.

Japanese all-girl R&B/hip-hop group XG, who are based in South Korea, saw a similar boost after J-Pop-loving influencers in Asia featured their music, causing ripples from Korea to Thailand to Indonesia. In many cases, trends reverberated as far as Europe and South America, eventually reaching North America.

My hypothesis is that interest in Japanese music, and the resulting uptick in sales, can be traced to growing interest in Asian culture, sparked by the K-Pop boom, in the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The overseas success of Japanese music on streaming platforms since 2023 comes in the context of online distribution of anime over the past several years, along with the streaming of K-Pop, which became massively popular from the late 2010s. For music from Japan to become established in the global market, there needs to be a steady, strategic output of a large volume of content during this window of opportunity. Now is the moment for ardent fans to provide strong backing to artists hoping to reach an international audience.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Gacha Pop icon, © Spotify; Ikuta Lilas of Yoasobi, at center, and members of Atarashii Gakko perform at the 2024 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in California, © AFP/Jiji.)