Yano Kōji on Why Japan Has to Slash Public Finance

Economy Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s Ballooning Debt

Known for being the greatest proponent of fiscal discipline in Japan’s Ministry of Finance, Yano Kōji has been a tireless and fearless advocate of austerity to senior figures in multiple governments. In an article published in the 2021 October edition of Bungei Shunjū, Yano dismissed the policy debate around that year’s LDP leadership race and the election for the House of Representatives as pork-barreling. He has also likened Japan’s government finances to “the Titanic sailing full-speed toward an iceberg.” The role of the Ministry of Finance is to support the cabinet, and as such, it is highly unusual for senior bureaucrats there to openly label a cabinet’s budget as wasteful spending. Some politicians even called for Yano’s dismissal.

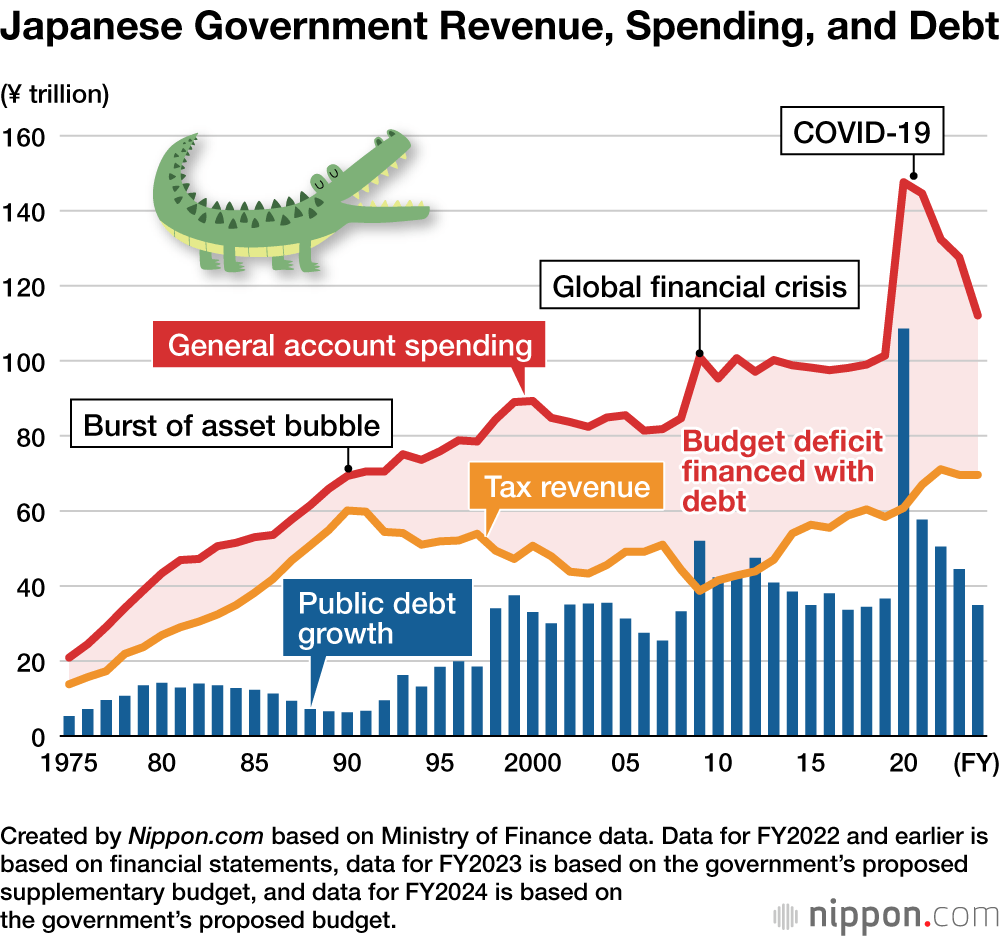

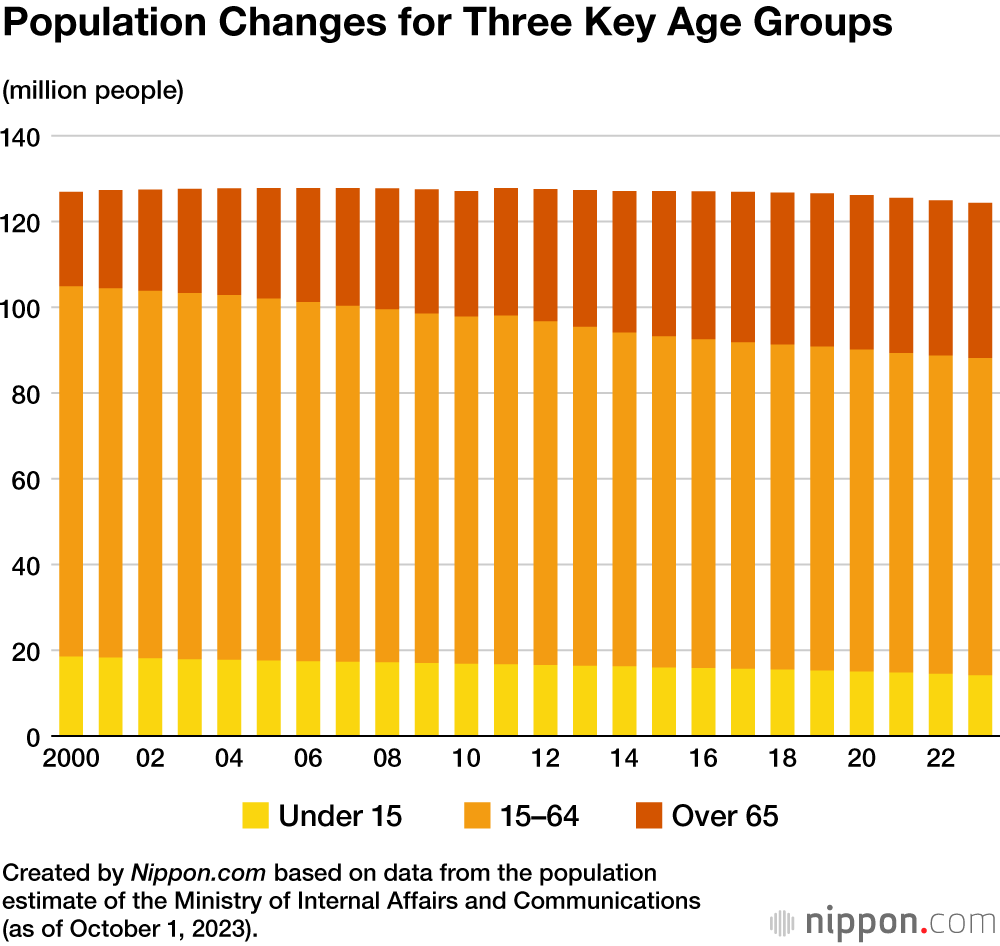

Yano is also known for his description of the graph of Japan’s public finances as a “crocodile’s mouth,” with an increasingly yawning gap between expenditures and tax revenues. “For half a century, Japan’s public finances have run deficits, not posting a single surplus,” he notes. “In Japan, sadly, the optimistic view that fiscal stimulus will increase tax revenue and improve the balance of payments is more strongly held than in any other industrialized nation. The reason that Japan’s government expenditure is increasing despite a falling population is that, due to the aging of the population, 800 billion yen is spent annually on social security, including healthcare, in-home geriatric care, and pensions. At the same time, because the working-age population is falling, the tax take is not growing.”

Disasters and pandemics have worsened Japan’s financial situation, to be sure. But while this is true to an extent, admits Yano, the economic swings triggered by disasters tend to disappear after a decade or so. “Ninomiya Sontoku, an agriculturalist of the late Edo period [1603–1868] who was responsible for turning around the finances of many feudal clans, would look back a hundred years when analyzing a clan’s financial situation and adjust for transient factors like floods and economic ups and downs. That perspective was essential to reforming public finance.”

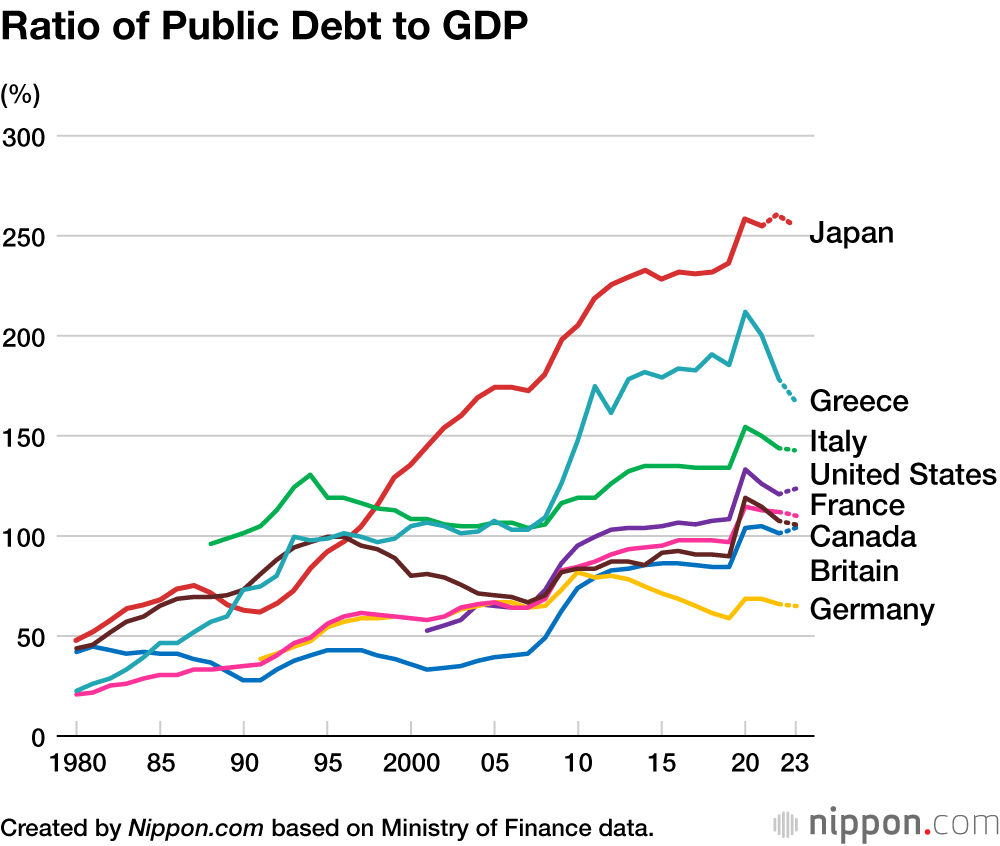

A comparison of Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio with that of other countries, explains Yano, shows that Japan has the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of the approximately 180 countries for which data is available. What’s more, for the last 30 years, things have only gotten worse: Japan’s debt has only ever increased, be it gradually or in major leaps.

According to Yano, “Unlike its overseas counterparts, the Japanese government has not repaid debt during boom times. While all countries deployed significant stimulus packages during the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States and Britain procured funding to cover this cost after the pandemic was over, while Germany and France put in place repayment plans for their COVID debt. Japan has done neither.”

Welfare Imbalance

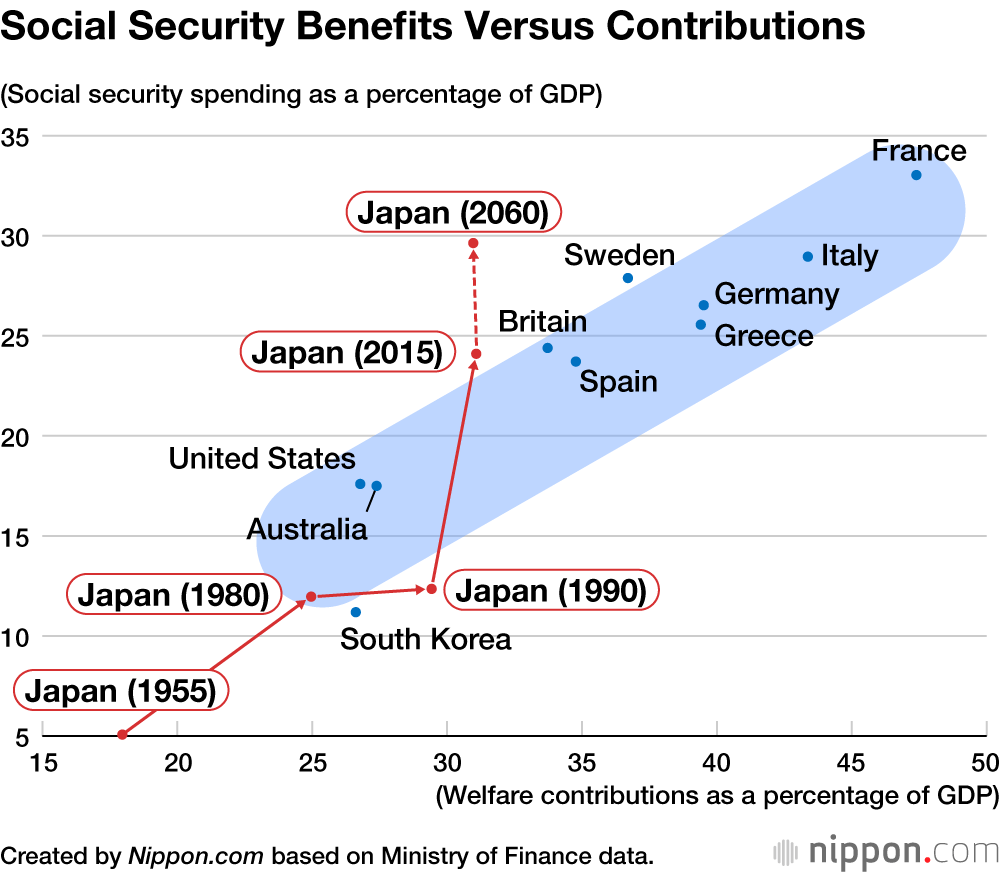

As the population continues to age, notes the former official, Japan’s finances will continue to worsen. “The United States is characterized by minimal welfare benefits but also low welfare contributions. Northern Europe, on the other hand, has a comprehensive welfare scheme matched with high contributions. Britain has moderate levels of welfare and moderate contributions. This situation reflects the choices of the respective populations.”

Many countries are concentrated in the blue band on the graph below, in which benefits are balanced by contributions. Japan currently deviates from this zone, with its population enjoying moderate levels of welfare despite low contributions. “As things stand,” says Yano, “Japan is projected to rise even higher on this chart by 2060. To restore balance, we need to choose between either fewer benefits, higher contributions, or a combination of both.”

The Advantages of a Higher Retirement Age

Both welfare cuts and increases in contributions cause pain, but according to Yano, the idea that we can hope for a miracle turnaround at some point has been completely refuted. “Japan needs to confront reality. If we are to ease the pain even slightly, people are going to have to retire later. While this means they will pay more in tax and insurance premiums, their individual incomes will also increase. If people can actually stay healthier by remaining in the workforce, increases in healthcare and geriatric care costs will be suppressed. Many Japanese express a desire to work into old age, and there are always many vacancies aimed at senior citizens. By creating a society with long life expectancies in which people can continue to work happily, both citizens and society as a whole will be happy.”

What, then, is an ideal retirement age? Yano has done some thinking on this as well. “The average life expectancy for Japanese men and women at the beginning of the twenty-first century was 80. It is now 85, and statisticians say that by the end of the century it will be 100. If average life expectancy increases by this much in the space of one century, surely people who used to retire at 60 will need to keep on working until they are 75. Some will accuse me of picking on the elderly, but I say that people should be allowed to work until near the end of their healthy lives if they want to.”

Under the current schemes in place in Japan, workers receive a pension at 65, the start of the “younger elderly” bracket, and starting at age 75, when the enter the “older elderly” bracket, they only pay 10% of their medical costs. Says Yano: “If we don’t redefine these age brackets, it doesn’t matter how much we tweak social security every year—it’s a drop in the ocean. If we fail to have a debate about raising the retirement age, the system will collapse.”

In 1963, there were only 153 people in Japan aged 100 or over. By 1981, this number had risen to 1,000, by 1998, 10,000, and by 2023, 90,000. Advances in medicine have brought about steady increases in life expectancy. Should the retirement age really be left at 65? While longevity is to be celebrated, the systems that support the elderly are also increasingly coming under strain, and healthcare costs are ballooning.

“Japan is the only country stupid enough to allow healthy senior citizens with 500 million yen in assets to contribute only 10 percent to their medical costs from age 75,” says Yano. “As life expectancies increase, there comes a need to redefine the term ‘senior citizen.’ We need to reflect changes in life expectancy in the system, in the same way that movements in prices and wages are reflected.”

Yano notes that China and South Korea, whose populations are ageing even faster than Japan’s, are watching Japan to see whether it fails or succeeds. How long will Japan cling to its definitions of “younger elderly” and “older elderly” as people age 65 and up and 75 and up, respectively? Japan is a world leader in having lots of problems: The solution in this case, argues Yano, is clear.

“If people say that they can’t work any longer, they must accept harsh reductions in benefits and higher taxes and insurance premiums. We’ll get nowhere if we keep on saying ‘no’ to everything. Our only option is to create a bright, long-lived society where people can go on working happily.”

Are Reformists Crying Wolf?

Yano has been warning of impending financial crisis for some time, but yet Japan has not gone bankrupt. As time goes on people inevitably begin to think of him and others in his camp as people crying about the wolf that never comes.

“While I can’t predict when it will happen,” says Yano, “if the current state of affairs is allowed to continue, one day a wolf really will come. When government finances are pushed to their limits, interest rates will definitely rise. This is a reality that no country throughout history has ever been able to escape.”

Some say there is nothing to worry about because only a small portion of Japanese government debt is owned by foreign nationals. Here, too, though, Yano sees cause for alarm. “While 97 percent of Japan’s government debt was once owned by Japanese nationals, the proportion is now around 85 percent. On the trading floor, 30 to 40 percent of cash bond trades and 60 to 70 percent of futures trades now involve foreign nationals. While there is a resoluteness in optimism, a biker doing 180 kilometers an hour on the Tokyo motorway who tells himself that he is immortal will eventually die in a crash.”

In the pond that is the Japanese bond market, notes Yano, there is a whale called the Bank of Japan that has sucked up over half of the water, namely Japan’s government bonds. “But when bond prices rise, the whale will become unable to suck up any more water,” he says. “Who will clean up the mega flood of government bonds that ensues when the whale progressively withdraws? Currency collapse, in the form of inflation and the weak yen, is already here.”

The wise learn from history what not to do, while the foolish do not learn their lesson until something bad happens to them, he argues. It’s the foolish people who triumphantly tell you that they still can’t see any wolf who will come in for a fall.

Yano does not shy from inconvenient truths or disguise his distrust of the politicians who are spending big in the run-up to the next round of elections. The fact that, after standing down as administrative vice minister of finance, Yano continues to go around the country on speaking tours, talking directly to the people, is testament to his belief that it is the voters—the people who choose the politicians—who have the power to change the government. Rather than being sucked in by the promises of tax cuts, subsidies, and stimulus packages that are rolled out before every election, by participating in a rational, fact-based debate, the Japanese people still have an opportunity to change their country.

(Originally published in Japanese based on an interview by Tani Sadafumi of Nippon.com. Banner photo © Nippon.com.)