Japan Looks to International Talent for Olympic Success

Sports Global Exchange- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Foreign Coaches of Japan’s Teams

The 2024 Paris Olympics will see the first appearance by Japanese men’s teams in basketball for 48 years (since Montreal in 1976), in handball for 36 years (Seoul in 1988), and in volleyball for 16 years (Beijing in 2008), not including the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, when Japan automatically qualified via the host country quota.

These three teams share one notable aspect in common: They are each led by a foreign coach. American Tom Hovasse, who coached Japan’s women’s team for the Tokyo Olympics, is now coach for the men’s team. The handball team was coached until recently by Dagur Sigurðsson, from Iceland, who previously coached the German national squad, and was once awarded IHF World Coach of the Year. Frenchman Philippe Blain, once coach of the French team, now heads Japan’s volleyball side.

Hovasse first came to Japan in 1990, and had stints playing for Toyota’s and Toshiba’s corporate teams. After retiring from competition, he took to coaching, including for Japan’s women’s squad from 2017 onward, attracting great attention when he led them to the silver medal three years ago at the Tokyo Olympics.

In an interview published on the official website of the International Olympic Committee, Hovasse is quoted as saying “When I was coaching the women’s team, I incorporated techniques and philosophy from the NBA, and a European style of play: what you might call a coaching style used with men’s teams.”

People are familiar with scenes of him fervently encouraging the players, but during his career, he has played pro ball for the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks and for a team in Portugal. In addition to his passion for the sport, he also has international experience and knowledge to impart to the Japanese athletes. His next challenge is in leading the men’s team to Paris.

Hovasse instructs the players in Japanese, rather than relying on an interpreter, based on his belief that “Even if I make mistakes, it’s better in my own voice.” (© Reuters)

Sigurðsson and Blain have experience in training national teams, and have strengthened the Japanese teams with their world-class coaching. Both of them have taken their skills around the world.

But with just six months remaining until the Paris Olympics, Sigurðsson suddenly indicated his desire to quit his role, perhaps to take up a new position coaching Croatia, which was due to compete in the Olympic qualification tournament in March. The Japan Handball Association is endeavoring to select a replacement coach, but this episode may cause headaches if they attempt to hire another foreign coach.

Blain, meanwhile, has signed a contract with the Japan Volleyball Association taking him through the Paris Olympics, but after that, he will coach a South Korean team, the Cheonan Hyundai Capital Skywalkers.

The Japanese team tosses Sigurðsson in the air in celebration after their success at the Asian Men’s Handball Qualification for the 2024 Olympic Games in October 2023, where they secured a spot in the upcoming Olympics for the first time in 36 years. (© Reuters)

Blain (at rear) watches a match at the Olympic Volleyball Qualifying Tournament in Finland, in September 2023. (© Jiji)

The German Who Revolutionized Japanese Soccer

Soccer opened the way for Japanese teams to adopt foreign coaches. Since the 1990s, the national squad has been coached by many coaches from outside Japan:

- Hans Ooft (Netherlands) 1992–93

- Roberto Falcão (Brazil) 1994

- Philippe Troussier (France) 1998–2002

- Zico (Brazil) 2002–6

- Ivica Osim (Bosnia and Herzegovina) 2006–7

- Alberto Zaccheroni (Italy) 2010–14

- Javier Aguirre (Mexico) 2014–15

- Vahid Halilhodžić (Bosnia and Herzegovina) 2015–18

Over 60 years ago, though, another coach from Germany laid claim to the title “Father of Japanese Soccer.” While Dettmar Cramer did not coach the national team, he came to Japan in 1960 as the first foreign coach in the country.

At the time, Japan was struggling to win international matches. The Japan Football Association appealed to the West German association to provide a coach, and of the many options available, Cramer was the person they selected. In his home country, among other things, he had served as the head coach of the Sport School in Duisburg.

After arriving in Japan, he stayed in the same accommodation as the national team, and on the field, he trained players beginning with the basics of kicking the ball. It was a time when grass playing fields were still a rarity in Japan. He helped spur rapid progress in the Japanese style of play with German-style theoretical instruction. Okano Shun’ichirō, who acted as his interpreter at the time (before becoming JFA president), recalls the manager: “Cramer introduced coaching to Japan. Before that, soccer was taught theoretically by people with no soccer experience. Cramer showed us how to play himself, building a foundation for soccer in Japan. He put us on track, giving us bright hope for the future.”

Japan went on to outperform Argentina and reach the quarterfinals as one of the top eight teams at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. From 1967, Cramer became an official coach for the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), and was sent around the world to provide instruction. The Japanese team went on to earn bronze at the Mexico Olympics in 1968, based on what they had learned from him.

This had a major impact on the Japanese sporting world as a whole. One outcome was the formation of the Japanese soccer league. When Cramer first came to Japan, knockout tournaments were the main form of domestic competition. Amateur players were unable to take long periods away from their workplace, and tournaments were held over just a few days, without having to tour the country. But Cramer felt the need for reform.

He believed that the level of competition would be enhanced through repeated play against stronger opponents, rather than teams bowing out after defeat. He was adamant that Japan needed a national league instead of tournaments.

The day after the closing of the Tokyo Olympics, Cramer took the opportunity to unveil his proposal at a gathering of soccer officials. “In order to boost the competitiveness of Japanese players and of the team, Japan must adopt a league match system similar to those operating in European countries. Japan needs to divide into four areas and form a league from the strongest 12 teams.”

In 1965, the Japan Soccer League was established in accordance with his proposal. This encouraged the formation of a succession of leagues by other Japanese sporting groups. It was a period of strong economic growth in Japan, and many companies strove to enhance their in-house sporting clubs as a form of publicity. The resulting invigoration of domestic sporting leagues went on to play a key role in bolstering national teams.

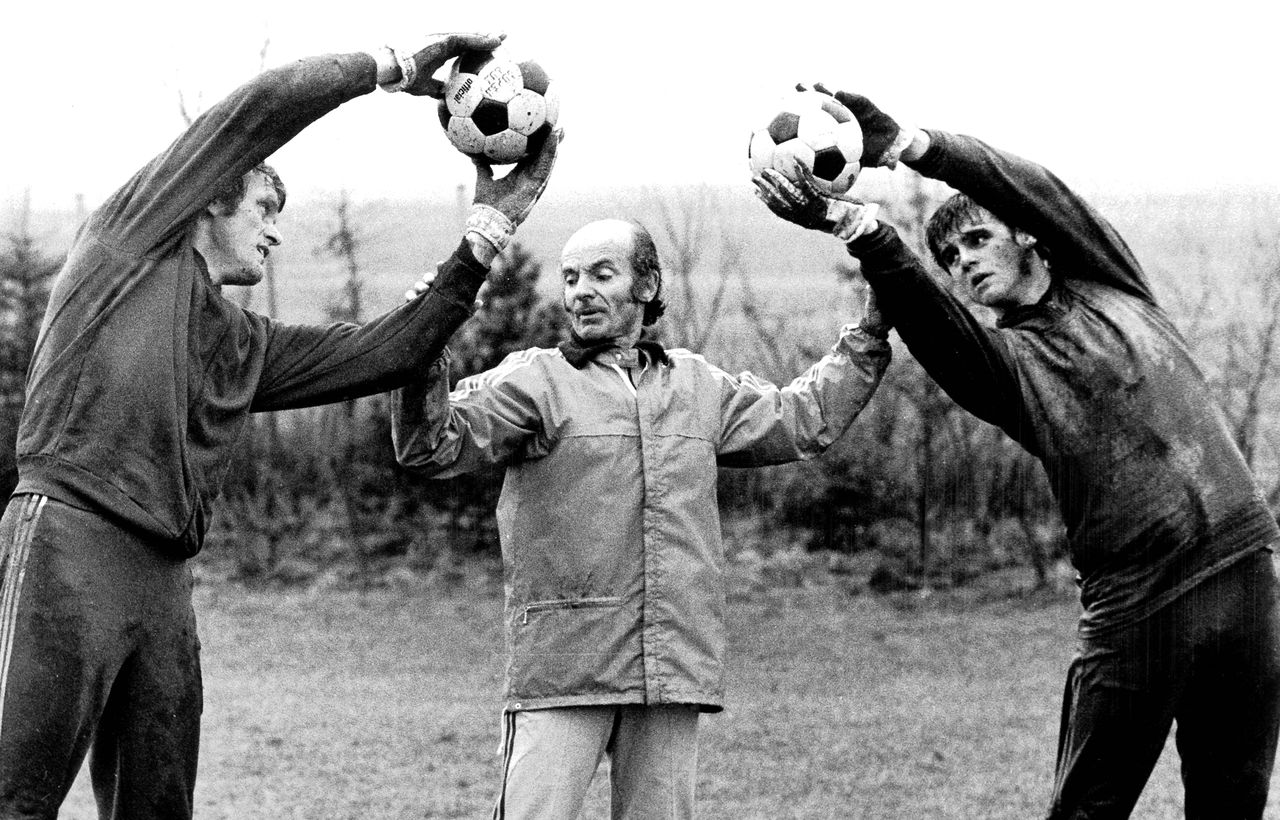

Cramer (center) during his time coaching German team Bayern Munich (1975–76). He coached Sepp Maier (left), also the West German national squad’s goalkeeper, leading the team to win the UEFA Championship. (© AFP/Jiji)

Globalization Leads Players Overseas

The 1990s saw major changes in the sporting scene both in Japan and abroad. After the collapse of Japan’s economic bubble, many companies decided to disband their sports teams. The competitive arena became less stable, and the country’s national squads suffered a notable deterioration in performance.

Overseas, the formation of the European Union enabled players to transfer more easily between countries, clubs became more internationalized, and the level of competitiveness rose rapidly. In addition, with the spread of pay-to-view satellite television, broadcasting rights soared in value, boosting the scale of the sporting business. As in Europe, professional sports in the United States began bringing more foreign players onto teams and became more globally oriented.

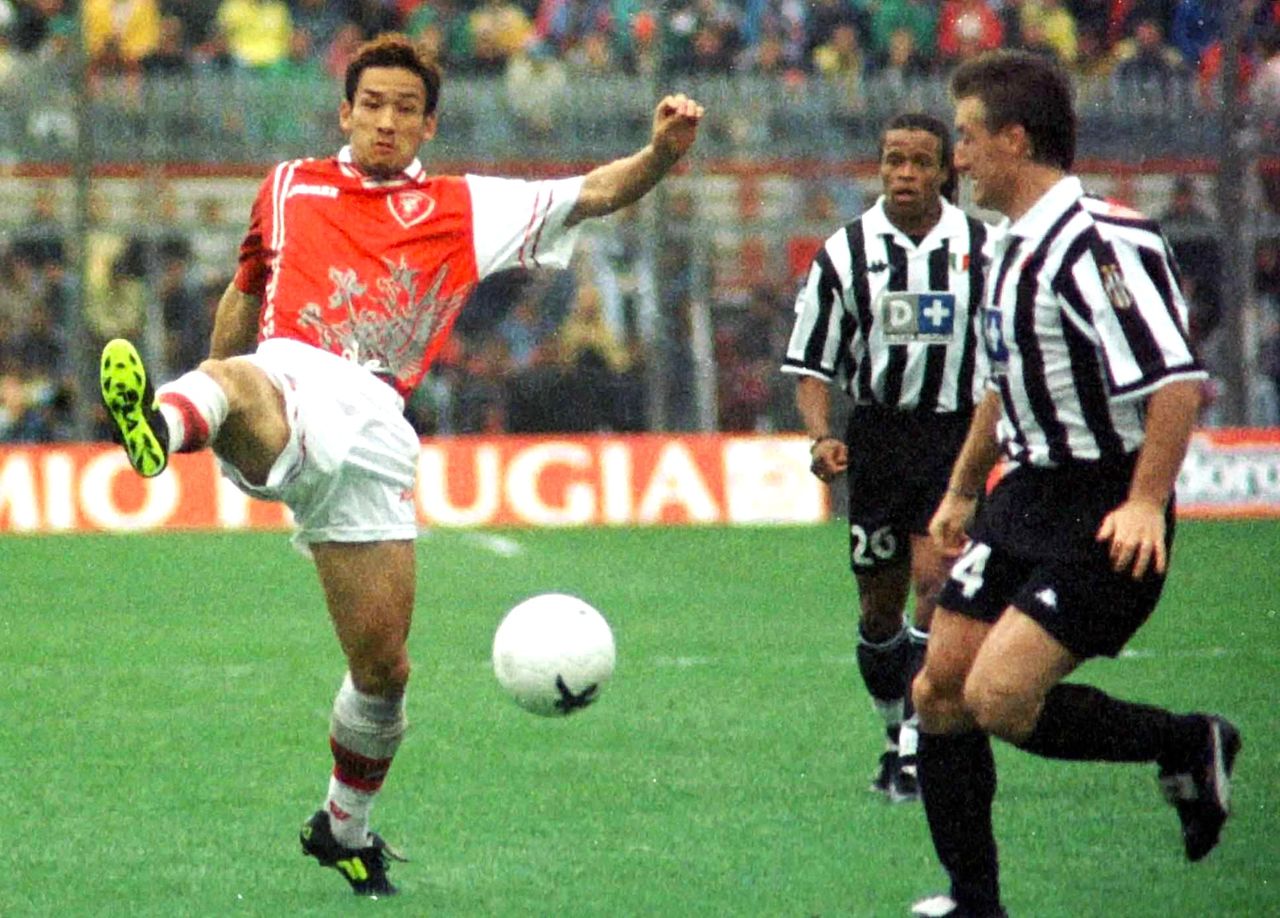

Japan’s J. League was also launched in 1993. Five years later, the Japanese men’s team made its first appearance at the World Cup, in France. At that time, all of the players were from the J. League. But after the cup ended, midfielder Nakata Hidetoshi transferred to Perugia, in Italy’s Serie A, paving the way for Japanese players to move abroad.

Nakata Hidetoshi (left), playing for Perugia, scores a goal six minutes into the second half in a match against Juventus on September 13, 1998. (© AFP/Jiji)

Since 2000, many players have transferred abroad after playing in the J. League, and the national team has matured to the point where it has managed to reach the World Cup on seven consecutive occasions. At the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, the Japanese squad of 26 had just 6 players from J. League sides.

Following the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s, though, domestic leagues for other team sports stagnated, impeding globalization. More recently, there has been a rise in regional-based clubs, and the foundation for competition is being rebuilt, exemplified by the launch of basketball’s B. League. Japan has also seen more of its players joining overseas teams.

The National Basketball Association has also been home to several Japanese players. Watanabe Yūta, who currently plays for the Memphis Grizzlies, was a driving force for Japan in reaching this year’s Olympics. Hachimura Rui, who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, will also join the team, helping boost its competitiveness even further. Japan’s volleyball squad includes Ishikawa Yūki and Takahashi Ran, who both play in the Italian Serie A, considered the global pinnacle of the sport. The Olympic qualifying handball team includes Japanese who play in Qatar, France, and Poland.

According to Ishikawa, a key player for Milano in Serie A and captain of the Japanese men’s volleyball team, “In terms of ability, compared with the Japanese team, Serie A club players are all regulars for their respective national teams, and are stronger individually than the Japanese side.” He initially moved to Italy over nine years ago, and has honed his skills competing in an international environment.

Ishikawa Yūki, who has played in the world-leading Italian Serie A since university, has been a key offensive and defensive player for Milano since 2022. (© Reuters)

The Need for a Virtuous Cycle

Although team sports in Japan are finally enjoying an upward trend, the future remains uncertain. One factor is the rapid decrease in player numbers due to the declining birthrate.

In March 2019, the Japan Sports Agency conducted a survey estimating the number of students belonging to the Nippon Junior High School Physical Culture Association, the All Japan High School Athletic Federation, and the Japan High School Baseball Federation. It forecast that, compared with the peak in numbers in 2009, the number of active students would decline around 30% by 2048. Team sports are expected to suffer over a 50% decrease in player numbers, which will make it harder to form teams in some parts of the country, causing a sharper decline in team sports than in individual sports.

Since 2023, an initiative has begun to transfer sporting clubs from public junior high schools to community clubs, but they struggle to secure coaching staff. Establishing a suitable environment for junior and senior high school sports will be a major issue for the Japanese athletic world moving forward.

Japan hopes to promote lower-ranked players to the top level, so they can compete at home and eventually internationally. Performance on the international stage also helps to bolster sports back home. But longer-term initiatives are essential if Japan is to develop a virtuous cycle for the rejuvenation of its team sports.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Japan wins in the final playoff for the men’s basketball FIBA World Cup, becoming Asia’s highest-ranked team in the tournament. Team and staff celebrate Japan’s success in qualifying for the Paris Olympics, the first time to qualify through their own efforts in 48 years, since Montreal in 1976. Taken in Okinawa, September 2, 2023. © AFP/Jiji.)

Related Tags

sports Olympics basketball soccer volleyball 2024 Paris Olympics and Paralympics