Will Real Wages in Japan Turn Upward?

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Large Corporations’ Wage Hikes Trickle Down

The shuntō, or “spring wage offensive,” held each spring in Japan seeks to strengthen labor’s bargaining position with management by having industrial labor unions join together in negotiating wage increases. Once a trend-setting labor union secures a large hike, the aim is to have similar increases spread to other labor unions and to small and medium-sized enterprises. In a survey of the 2023 spring wage offensive published by Rengō, the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, on May 10, the labor unions of large companies with 1,000 or more employees that negotiated on an average wage basis achieved an increase of 3.73% for the component corresponding to an annual wage increase and an increase of 2.17% for the base pay component. These are large increases compared to offensives in recent years.

Labor unions of small companies with 99 or fewer employees that negotiated on an average wage basis achieved an increase of 3.03% for the component corresponding to an annual wage increase and an increase of 1.83% for the base pay component. Labor unions of small companies that settled for such increases totaled 1,417 (representing 62,080 union members). Compared to the final spring wage offensive survey for 2022, published on July 5, 2022, some 60% of labor unions settled on wage increases as of May 2023.

The base pay component represents an increase of wage levels through the revision of existing wage schedules, while the total annual wage increase includes components to bring employees’ wages in line with those earned by longer-serving employees, in accordance with the existing wage schedule and based on labor agreements or rules of employment.

Large companies with 1,000 or more employees took the shuntō lead in setting wage increase rates. While the rates achieved by labor unions of small companies with 99 or fewer employees were somewhat lower, they do still suggest that wage increases are spreading.

Regarding the annual bonuses received by full-time union members, labor unions negotiating monetary amounts achieved a bonus of ¥1,597,406, or an increase of ¥33,352 over the previous year. The many labor unions negotiating bonuses by the number of months of salary achieved a bonus of 4.88 months, or a decrease of 0.01 months from the previous year. Wage increases in Japan have tended to be made through bonuses to avoid their becoming a part of fixed labor costs. The spring wage offensive of 2023 suggests the possibility that wage increases are shifting to the increase of base pay. This is a significant change for the sustainability of wage increases in the medium to long term.

Reaching Companies Without Labor Unions

As reported in the Survey on Wage Increase of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, 21.2% of companies had labor unions in 2022, meaning that employees at a large majority of corporations do not have union representation. Moreover, the percentage of companies with unions differs significantly between industry categories. The ratio of companies with labor unions reached 58.0% for the category of electricity, gas, heat supply, and water and 57.3% for mining and quarrying of stone and gravel, but only 3.6% for medical, health care, and welfare, 5.8% for living-related and personal services and amusement services, and 6.6% for accommodations, eating, and drinking services.

The Survey on Wage Increase surveys private-sector companies with 100 or more regular employees. A separate survey by the ministry indicates that 0.8% of companies with 99 or fewer employees were estimated to have labor unions in 2022. When small companies are included, the percentage of companies with labor unions becomes even smaller. Thus, an important point raised by the Rengō survey is how to spread increases to companies without unions.

The Survey on Wage Increase also discloses that 26.0% of companies with labor unions did not make wage increase demands in 2022. It is reasonable to think that there are fewer opportunities to negotiate hikes in nonunionized companies. Given a historically high rate of inflation, opportunities for labor and management to sincerely discuss the possibility of wage increases have become all the more important.

Hoping for Further Real Wage Growth

The Survey on Wage Increase indicates that most companies consider April, the beginning of the standard Japanese fiscal year, to be the applicable period for revising wage rates in relation to the spring wage offensive. There are, however, companies that negotiate wage rates in later periods, particularly in each of the months to July. As I write this article, final data is available only to February in the Labor Ministry’s Monthly Labor Survey. The analysis of wage trends reflecting this year’s spring wage offensive is still a matter for the future. For this reason, in the paragraphs to follow, I will analyze the pertinent points for examining the future direction of the real value of wages.

First, total real wages decreased 2.4% in February 2023 compared to February 2019. The analysis of contributing factors reveals that the total nominal cash earnings of full-time workers grew 2.3% and the corresponding cash earnings of part-time workers grew 0.5%. Meanwhile, consumer prices made a substantial negative contribution of –5.0%. In addition, the growing share of the workforce occupied by part-time workers, whose wages tend to be less than the average, contributed –0.2%.

Focusing on the total nominal cash earnings of full-time workers, special cash earnings, which include nonscheduled cash earnings and bonuses, made a negative contribution between 2020 and 2021. In contrast, the contribution of scheduled cash earnings did not change significantly. Moving forward to 2022, the positive contribution of mainly scheduled cash earnings drove the growth of total nominal cash earnings (Figure 1).

There are two components to the wage increase rate negotiated in the spring wage offensive: an annual overall wage increase and an increase to base pay. The rate of the hike will be experienced by individual workers as an increase of wages. However, in comparisons with past years as macroeconomic statistics, the base pay component tends to appear as a change in scheduled cash earnings. In the recent Rengō survey, base pay grew 2.14% for companies with labor unions. Should wage increases spread to small and medium-sized companies without labor unions and should scheduled cash earnings in the Monthly Labor Survey increase 2.14%, there is the possibility that real wages’ rate of change will rise to nearly zero.

Moreover, in the ESP Forecast of the Japan Center for Economic Research (a survey of the predictions of some 40 private-sector economists), the upsurge of consumer prices (all items excluding fresh foods) is forecast to gradually stabilize beginning in the fourth quarter of 2022. Should the negative contribution of consumer prices diminish, this, in combination with the spread of wage increases referred to above, may enable real wages’ rate of change to turn positive in the medium term.

Greater Variation in Hourly Pay?

In considering the future direction of real wages, attention must also be given to the way nominal wages vary among workers. Since all workers are equally affected by the surge of consumer prices, even if average real wages’ rate of change is close to zero, when nominal wages vary widely among workers, it is possible that the spread in wages will grow between workers whose real wages have increased and workers who are unable to maintain the real value of their pay.

I have used the public data of the Monthly Labor Survey to create a simple index of the variation of nominal hourly wages by employment category, industry, and business size. This index should be viewed with some latitude since it does not fully coincide with variances derived from individual data. That said, we see in Figure 2 that, after narrowing from 2020 to 2022, the variation of nominal hourly wages has widened since 2022.

The figure shows that the indices have trended similarly following the financial crisis of 2008 and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011. This may be because in recessions brought on by slumping stock prices or a natural disaster, many companies reduce wages centering on nonscheduled cash earnings and bonuses, which diminishes the variability of nominal hourly wages. When the economy subsequently recovers, companies will differ in their capacity to increase wages, thus boosting the variability of nominal hourly wages.

To identify the industries where wage variability for full-time workers is increasing, I compared the period of February 2023 and January 2022 for the variance between business places with 500 or more employees and those with 5 to 29 employees. This showed that the variance was ¥223 for accommodations, eating, and drinking services, ¥193 for scientific research, professional, and technical services, ¥164 for real estate and goods rental and leasing, and ¥161 for the wholesale and retail trade (Figure 3).

For example, in the industry of accommodations, eating, and drinking services, the difference in nominal hourly wages by business size was ¥567 as of February 2023. Assuming that a worker works nine-hour days for five days a week, the difference in total wages by business size would be about ¥1,327,000 after one year (about 52 weeks). The increase of ¥223 between January 2022 and February 2023 would mean an additional yearly difference of about ¥522,000.

Summarizing the above, the following are the main points for considering the future direction of real wages.

Since companies will differ in their capacity to increase wages during economic recoveries, the variability of nominal hourly wages will tend to increase during such periods. This variability has been increasing since 2022. Even if the rate of change of average real wages approaches zero once the hikes negotiated in the spring wage offensive are reflected in economic statistics, the focus of analysis should not be limited to average wages but should also include the trend for their variability.

With respect to wage negotiations with small and medium-sized enterprises, rather than simply applying the wage increase rate of large companies taking the lead, it will also be necessary to factor in the increased difference in nominal hourly wages with large companies ahead of wage negotiations.

(This article represents the views of the author and should not be taken as the official view of affiliated organizations.)

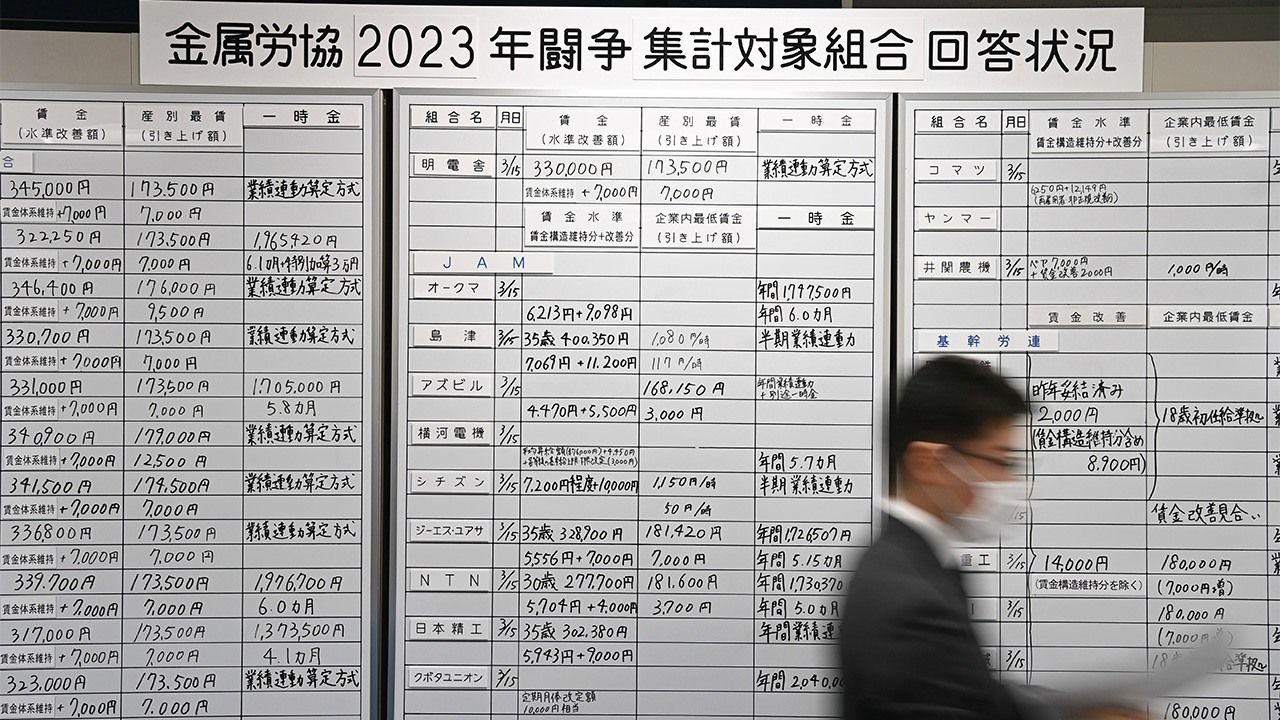

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A board at the Japan Council of Metalworkers’ Unions showing replies to labor-management negotiations in Chūō, Tokyo, on May 15, 2023. © Jiji.)