Too Hot to Fight? A Quiet Summer for Japan-South Korea Relations

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Month Focused on the Past

August is usually a turbulent month for relations between Japan and South Korea. This is mainly due to the sheer number of anniversaries that put the spotlight on the two countries’ different interpretations of history. In this month, Japanese people look back to 1945 and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9, followed by Japan’s surrender on August 15.

For South Koreans, however, the latter date is National Liberation Day, marking the end of Japanese colonial control. It is also the day that Korea’s north-south split began, as the country was divided into two zones of occupation by US and Soviet forces at the 38th parallel. South Korea became independent on the same day in 1948. Meanwhile, August 29 is the anniversary of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910. Further, on August 14, 1991, Kim Hak-sun brought the comfort women issue to light by making public testimony of her own experience. Since 2017, South Korea has designated August 14 as Japanese Military Comfort Women Victims Memorial Day.

There were also particular circumstances in August 2020. A South Korean court ruling on August 4 allowed for the seizure of Japanese corporate assets to compensate Koreans for forced labor while under colonial rule. August 24 was the deadline for declaring withdrawal from the General Security of Military Information Agreement, as South Korea had threatened to do. Many were worried about the prospect of the two countries clashing over their many unsettled issues, including those relating to forced labor and comfort women. And yet, this kind of confrontation did not come to pass.

Unusual Calm

Although the August 4 court ruling received a fair amount of coverage in Japan, the media emphasized that several more months would be needed to complete further procedures before liquidation of assets would be possible.

The Japanese government remained collected throughout. While it issued public statements expressing concern, it did not rush to implement countermeasures discussed in some quarters, such as suspending visa exemptions or raising tariffs. The South Korean side was similarly calm. President Moon Jae-in did not direct harsh words at Japan in either his comfort women memorial speech on August 14 or on National Liberation Day the following day.

Since the South Korean government took back its decision to withdraw from GSOMIA last November, it has reserved the right to scrap it at any time. It has not taken any action along these lines, though, and the situation remains at a standstill.

This is a very different state of affairs from last year. In the summer of 2019, Japan and South Korea were already at loggerheads over the previous October’s ruling by the Supreme Court of Korea ordering Nippon Steel to compensate forced laborers. Japan’s tightening of controls on exports of semiconductor materials to South Korea in July 2019 raised tensions further.

Bilateral rancor reached its peak when the Japanese government decided to remove South Korea from its “white list” of trading partners that enjoy simplified export controls on August 2, sparking Korean boycotts of Japanese products and tourist destinations. Under these circumstances, the South Korean government announced its intention to scrap GSOMIA on August 23, so the deterioration of the two countries’ relations extended from historical perception through economic issues to national security.

Dealing with COVID-19

Why did August 2020 pass so peacefully? It has been suggested that the main reason was the huge slowdown in economic and social activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Both governments were rushed off their feet dealing with their respective second waves of infection.

However, when faced with the menace of the coronavirus, some political leaders have tried to unify the public by pinning responsibility for the chaos on another country or playing up an external threat. US President Donald Trump could be seen as the archetypal example in his attempt to pass much of the blame to China through his repeated use of the phrase “Chinese virus.”

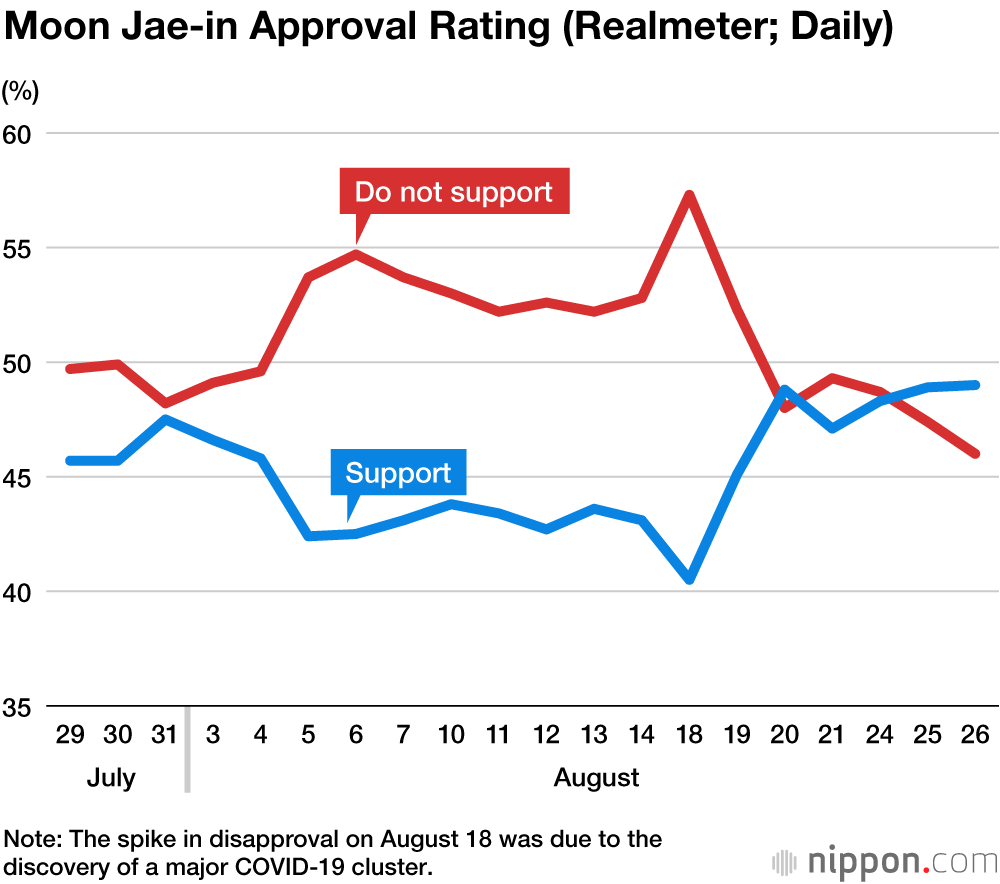

Some analysts have identified governments in Japan and South Korea as showing the tendency to step up their rhetoric against the other nation when domestic support is waning, because hardline policies provide a boost in the polls. If this is the case, the two administrations—both struggling with rapid slides in popularity—might have sought to turn their situation around through a tough stance at the level of 2019 or even greater.

Neither country chose to do so. Their decisions were connected to rapid declines in interest concerning bilateral relations in both nations.

No Boost from the Hard Line

Until around 2012 in South Korea, it was certainly true that speeches related to policies on Japan by the president and government figures affected leadership and governing party approval ratings. This correlation diminished through the Park Geun-hye administration (2013–17), and has almost vanished under Moon.

In weekly polls conducted by Gallup Korea, almost no respondents say that Japan policies are a factor in their approval of the president. Speeches about bilateral relations this August by major government figures have also had close to zero effect in lifting presidential support.

In Japan too, the diplomatic attitude to South Korea is much less significant for cabinet approval ratings than it once was.

Unlike South Korea, where both conservatives and progressives in the government and opposition take a tough stance against Japan on historical issues, voters in Japan who want to see hardline policies against its neighbor are overwhelmingly conservative. The core of the present Japanese government consists of conservatives with a strongly nationalistic character, and it has always had the backing of those who wish for such actions.

This means that there is little chance of attracting further support by taking an even firmer line on South Korea. In the economic and social turmoil of the COVID-19 crisis, there is almost no incentive for Japan’s government to prioritize hardline policies.

Unresolved Issues

Naturally, this does not mean that we are at the start of sincere efforts to resolve historical perceptions issues between the two countries. The decreased interest in bilateral relations means there is also no incentive for the governments to tackle these problems.

As a result, while the unresolved issues are left to one side, former forced laborers and comfort women are passing away one by one. As the Japanese and South Korean governments trumpet their opinions and maintain their opposition to each other, nobody is reaching out to help the victims themselves.

This is particularly conspicuous within the Moon administration. While it claims to center the victims in its actions, it has not implemented any measures for actively supporting them. Consequently, with an average age of more than 90, they are dying without seeing any settlement. Comparing Moon with Roh Moo-hyun, who he served as senior presidential secretary, and other former South Korean leaders, Moon’s indifference to the victims is striking. Here, one can clearly observe the greatly diminished concern with bilateral history issues among the South Korean government and public.

What lessons will the unexpectedly quiet summer leave for future relations between Japan and South Korea? Will the lull and status quo continue, or will some new incentive lead to renewed conflict or sincere negotiation? It is a situation that demands continued attention, including toward the Korea policies of the Japanese government under its new leader.

(Originally written on August 27 and published on September 4, 2020, in Japanese. Banner photo: South Korean President Moon Jae-in gives a speech in Seoul on National Liberation Day on August 15, 2020. © Yonhap News/Newscom/Kyōdō News Images.)