The Evolution of “Boys’ Love” Culture: Can BL Spark Social Change?

Culture Society Manga Anime Books- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Boys’ love television dramas from Thailand have recently garnered a worldwide cult following. 2gether, a love story of two male university students, won many fans, with an official YouTube channel with English subtitles—even topping Twitter’s global trends list. Thai BL television dramas, available through video streaming services and satellite channels, have also gained a fan base in Japan.

Boys’ love originated in Japan, spreading globally as one genre of manga and anime. According to Fujimoto Yukari, a researcher of girls’ manga and gender issues, there is growing interest in BL culture in Thailand, China, Taiwan, Korea, and other Asian countries. Each evolved along a unique path, depicting the complexities of social circumstances in which LGBT people find themselves. But what are the origins of BL in Japan, and how has the genre changed over time?

The Revolution of Takemiya Keiko and Hagio Moto

Fujimoto believes that BL in the general sense first emerged as shōnen-ai (adolescent boys’ love) in girls’ manga in the 1970s, offering depictions of strong bonds and erotic encounters between adolescent boys.

Until the mid-1960s, most manga for girls were created by male artists. But in the late 1960s, a new wave of female artists emerged, born after the war. Suddenly, female artists not much older than their audience began producing manga that they themselves wanted to read. This spawned the adolescent boys’ love concept. Previously, girls’ manga featured female lead characters, inevitably limiting expression, due to women’s position in society. With male protagonists, creators could depict more independent and proactive characters and include bold erotic narratives. This realization offered an opportunity, and female readers fervently embraced these works depicting attachment and love between male characters.

A group of female writers, including Takemiya Keiko and Hagio Moto, produced the first shōnen-ai (adolescent boys’ love) manga. They were labeled the “Year 24 Group of Flowers,” a reference to their generation’s brilliant performance and their birth around 1949 (Showa 24). The creators consciously aimed to rock society through new forms of expression in manga. In the autobiographical manga Shōnen no na wa Jirubēru (The Boy’s Name is Gilbert), Takemiya said she had aimed to spark a revolution through her girls’ manga.

A 2019 rerelease of Takemiya’s Shōnen no na wa Jirubēru (The Boy’s Name is Gilbert)

Hagio Moto launched her series Pō no ichizoku (trans. The Poe Clan) in 1972. It tells the exploits of the young-looking “vampanellas” (vampires) Edgar and Alan across the centuries, and is considered an immortal title in girls’ manga. She followed this in 1974 with Tōma no shinzō (trans. The Heart of Thomas), a series set in a German boarding school.

Then, in 1976, Takemiya began her Kaze to ki no uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees) series, considered the pinnacle of the shōnen-ai genre. The manga depicted the same-sex love of the handsome young Gilbert, but also included vivid scenes of rape and incest, sparking a sensation.

At the time, the monthly Bessatsu shōjo comic, featuring stories by Hagio and Takemiya, sold over a million copies an issue. It was a brave new world, where stories published in mass media reflected the values of young women born after the war.

In the late 1970s, many magazines carried works featuring male-male relationships. Then, in 1978, a magazine dedicated to the genre was released: June. It was known for its strong aesthetic focused on beautiful youth, and featured culturally aware sections on literature, novels, art, and movies.

Yaoi Spreads Worldwide

The late 1980s saw a sharp rise in derivative works known as yaoi, parody manga published in dōjinshi—amateur, self-published magazines. The earliest of these parodied the boys’ manga Captain Tsubasa. Yaoi take characters from famous boys’ manga and anime and recast them in romantic situations. Commercial BL emerged from such yaoi comics, evolving from tales of adolescent love to create more upbeat entertainment.

Publishing houses realized the commercial value of yaoi in the early 1990s, launching dedicated BL magazines. Authors who had originally found fame in dōjinshi secured offers to draw creative manga. Thanks to the launch of BL magazines such as Be × Boy, BL became an established commercial genre. But it was the manga artist Ozaki Minami, originally a yaoi author, who sparked the worldwide fever for Japanese BL with her manga Zetsuai 1989 (Absolute Love 1989). It ran in Margaret, a mainstream weekly girls’ comic magazine, and was supposedly an original creation. But, although the characters and storyline were new, it was obviously inspired by Captain Tsubasa, placing the work in the yaoi genre.

BL in Asia and Regulation of Expression

Today, there are many audaciously erotic commercial BL. Indeed, until recently, Japan saw little censorship of artistic expression in BL works. Fujimoto believes that the freedom of expression that exists in contemporary Japan is a reaction against regulation of free speech during World War II.

She explains that people who understand the titanic shift in postwar values, particularly the older or more powerful, including conservatives, are most aware of the danger of legally regulating freedom of expression. Conventional Japanese respect for logic and morality permits fantasy to exist as a form of stress-release. With BL, graphic erotic content is seen as distinct from pornography because it merely emphasizes the relationship between two characters. Also, erotic material for women has rarely been taken seriously. But recently, BL has been subject to stricter regulation. In Tokyo and other jurisdictions, BL works are increasingly being designated as harmful literature.

The situation varies in other Asian countries. In China, BL novels enjoy great popularity, but love scenes between men cannot be included in television dramas. Chen qing ling (The Untamed), a historical-fantasy television drama, was based on an online BL novel, but was reframed for television as a “bromance” depicting the strong bond between the male characters. Expressions of love between the two were only insinuated. Even writing BL novels entails risks.

Fujimoto says that the Chinese government does not stipulate what is subject to censorship, but intimate scenes are risky. Twice, online BL works have led to the laying of charges. In 2018, a BL creator received a 10-year prison sentence for publishing without government approval (China has a license system). But BL authors have not given up, in spite of the dangers they face, and they have a dedicated fan base.

BL manga are also popular in South Korea, but the country has strict regulation on sexual representation. Fujimoto believes that social factors make life in Korea more difficult for LGBT people than in Japan. In contrast, same-sex marriage was legalized in Taiwan in 2019, and BL fans who attended a dōjinshi event there had actively participated in the movement that sought its legalization.

Thai BL Dramas Win Greater Acceptance for LGBT People

Thailand in particular is seeing a blossoming of its own BL culture—especially TV dramas.

Fujimoto says the history of BL series in Thailand dates back to 2013, when the first genuine BL drama was screened. In 2016, a series called Sotus was a huge hit. But BL has only recently become mainstream. Now a diverse range of BL dramas have been produced, offering a connection between female BL fans and gay people. The drama Dark Blue Kiss raised issues including discrimination and coming-out to parents, but also depicted love scenes that appealed to a yaoi fan base. It was crafted so that the audience would naturally support the lead couple.

There are significant moves towards official legal recognition of gay couples in the country. In July 2020, a civil partnership law was approved by the Thai cabinet, allowing same-sex couples to adopt children and pass on inheritances. If approved by the parliament, it will be a major step toward the realization of same-sex marriage.

The Yaoi Controversy—The Gap With Reality

Unlike in Taiwan and Thailand, in Japan, there is a deep discrepancy between the lives of actual gay men and characters in BL and similar works. Fujimoto believes this division is why the genre does not bring about support or solidarity with gay people in Japanese society.

The early 1990s saw fierce debate on yaoi in a feminist magazine. Antagonism originated with comments that yaoi and BL were treating gay sex frivolously, fetishizing gay people, and fantasizing about and imposing aesthetic norms upon them.

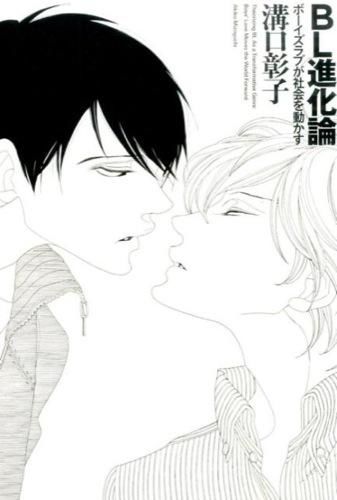

The 2015 BL Shinkaron—Bōizu rabu ga shakai o ugokasu (The Theory of BL Evolution and Its Impact on Society).

The man who posted these criticisms of BL said that, when he was young, he believed that only he was gay, but he was saved by male-male love stories such as Kaze to ki no uta. However, yaoi and other fan fiction works began as parodies of manga and anime, and are intended as fantasy. The authors clearly have no interest in real gay people. Fujimoto feels this was one factor that drew criticism of BL.

But this “yaoi controversy” has also led to gradual reevaluation of forms of expression by both BL authors and readers. In BL shinkaron (The Theory of BL Evolution), the lesbian activist and scholar Mizoguchi Akiko writes that, from the late 2000s, talented authors have emerged to produce a new style of BL that depicts male-male relationships in greater complexity and with more sensitivity.

BL has evolved into a genre offering limitless potential to depict new types of relationships removed from the social norms that constrain male-female relationships. They have achieved a new degree of diversity and refinement. With the upcoming Tokyo Olympics, both the government and mass media have led the call for greater diversity and inclusion, including LGBT people. The general mood is gradually changing in society.

“Missing Link” to Break the Curse of Normality

Fujimoto believes that television dramas provide a “missing link” to bridge the gap between BL fiction and gay people. Until recently, BL was limited to manga and novels. But TV dramas, with human actors, create a natural connection with reality, despite obviously being fiction. Fujimoto feels that they produce a subconscious change in the perception of viewers.

Fujimoto points to Ossanzu rabu (Ossan’s Love), a 2018 hit series that spawned a movie. She feels that the series was a carefully crafted work of entertainment, with a casual but considerate approach that was well-received in the gay community.

Another example is Kinō nani tabeta? (trans. What Did You Eat Yesterday?), serialized in a boys’ manga magazine by the BL author Yoshinaga Fumi. It too was turned into a television drama. The story depicts the happy home life of a middle-aged gay couple—one a lawyer, the other a hairdresser.

In Fujimoto’s opinion, conventional norms in Japan tend strongly to condemn those who strayed from social standards, leading to their misfortune. There was a subconscious discrimination, even among the young, that, because gay people were abnormal, they deserved pity and needed help. Now, there are signs of change. Fujimoto believes that if people watch dramas about ordinary gay couples enjoying in daily life, and realize their common ground, it might spark change in society.

The depiction of gay male couples is also certain to change perceptions of the male. Kinō nani tabeta? shows Shirō, the lawyer, preparing meals at home each day. Such a realistic portrayal may help young people to free themselves from the bonds of stereotypical masculinity. But Fujimoto fears the value of BL has diminished with the recent growth in BL works that simply cast two heartthrob actors to create a hit series. She hopes that future productions will aim for a higher quality of dramatic presentation.

Meanwhile, with the greater public awareness of BL manga, Momo to Manji (Momo & Manji), a historical manga set in the Edo period, was the first BL work to win a manga award at the Japan Media Arts Festival, organized by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs.

So what is the significance of BL today?

Fujimoto believes that BL works are now shattering social norms, conventional wisdom, and stereotypes by providing sensitive depictions of the diversity of human relationships. Realistic BL have reduced the gap between fiction and real life, and with the changes slowly taking place in countries like Thailand and Taiwan, BL depicting ordinary life may casually seep into people’s consciousness, inaugurating a new era.

(Originally written in Japanese. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner photo: A promo still from the popular Thai BL drama series 2gether. © GMMTV.)