Closing for the Night: Japanese Convenience Stores Weigh Dropping 24-Hour Service

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Changing Times

Faced with a changing demographic landscape, Japan is starting to question whether it still needs 24-hour convenience stores. The debate started in February 2019, when an owner of a 7-Eleven franchise in Osaka shortened his shop’s business hours after struggling to adequately staff the store. Unhappy with the move, executives at Seven-Eleven Japan threatened to cancel the franchise contract unless the owner reinstated the 24-hour policy. The media quickly picked up the story, sparking a vigorous and ongoing public examination of the need for stores to stay open around the clock. Wanting to avoid a looming PR disaster, Seven-Eleven Japan eventually backed down, and in March started testing reduced opening hours at outlets around the country.

(On October 21, Seven-Eleven Japan announced it would issue a new set of guidelines to its more than 20,000 outlets nationwide, clarifying procedures for halting 24-hour operations. Of the 200-plus outlets currently testing shortened business hours, 8 will be allowed to close from 11:00 pm to 7:00 am beginning on November 1.—Ed.)

Twenty-four-hour service has long been the hallmark of the convenience store model—one that, according to some, parallels Japan’s work culture of excessive overtime. Konbini, as the shops are known colloquially, started to take off around the same time as Japan’s asset-price bubble shifted the economy into overdrive, turning long hours at the office into an unquestioned virtue for the nation’s corporate warriors. Open around the clock, convenience stores fit seamlessly into this nonstop work ethic—popular energy drink Regain summed up the zeitgeist, winning “word of the year” honors in 1989 with its ad campaign fervently asking: “Japanese businessman! Can you fight 24 hours a day?”

Today, convenience stores are a ¥10 trillion industry in Japan. However, consumer habits are changing as the country ages and people live longer—Regain, once an elixir of energy, now touts products for “the era of 100-year lives.” This begs the question of whether the 24-hour business model that long defined convenience stores is still in step with the times.

Kings of Convenience

In his 2002 book Konbiniensu sutoa no chishiki (Understanding Convenience Stores), the economic scholar Kinoshita Yasushi points to a 1976 television advertising campaign by Seven-Eleven Japan as a factor establishing the convenience store model as it is known today. The advert featured a catchy jingle that summed up a satisfying shopping experience based on 24-hour service, nearby locations, and a wide selection of merchandise.

Taking a look at each of these aspects, there is real benefit from a consumer standpoint in having access to a well-stocked store that is accessible around the clock. A typical outlet carries a broad array of food items, daily necessities, and stationery goods, as well as the latest newspapers and magazines. Although drugstores have boosted their appeal by expanding their line-up of food, convenience stores still hold an advantage in terms of selection and by the fact that they never close.

Compact convenience stores have expanded into diverse locations, flourishing particularly in residential areas that are typically off limits to large supermarkets and department stores. According to the Current Survey of Commerce published by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, as of June 2019 there were more than 56,000 convenience stores in Japan, compared to roughly 16,000 drugstore outlets and 5,000 supermarkets.

Since the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, convenience stores have increasingly taken on a social infrastructure role, serving as lifelines for communities when disaster strikes. Abundant in number and boasting robust supply chains, convenience stores are often one of the few places during emergencies where residents can find daily necessities, and increasingly local governments are relying on the relief capabilities of stores when drawing up disaster plans.

A Smorgasbord of Services

The convenience store model in Japan differs starkly from countries like the United States, where these chains are also a part of the consumer landscape. Japanese konbini typically carry a wide assortment of fresh foods, ranging from bentō meals and rice balls to fried chicken to freshly brewed coffee. As competition has heated up, outlets have bolstered their selection with private-label goods in an attempt to woo customers.

Customers also visit convenience stores to make photocopies, withdraw cash at in-store ATMs, and purchase tickets for concerts and transportation. Other services include arranging to send or pick up packages with a delivery company, paying utility bills, and picking up copies of certificates of residence or other official documents. Most shops also have public restrooms. As Japan’s population ages, stores have rolled out delivery services and mobile outlets to serve residents in rural districts who have trouble accessing shops.

Another defining feature of Japanese convenience stores is cleanliness and a high level of customer service. Staff are thoroughly trained on store procedures and are typically polite and quick to ring up purchases or answer questions.

An Aging Clientele

Although convenience stores are deeply entrenched facets of Japanese society, they are not immune to market shifts and must change with the times. The 24-hour business model has served the industry for decades, but demographic pressure, labor shortages, and a changing customer base have gradually reduced its importance.

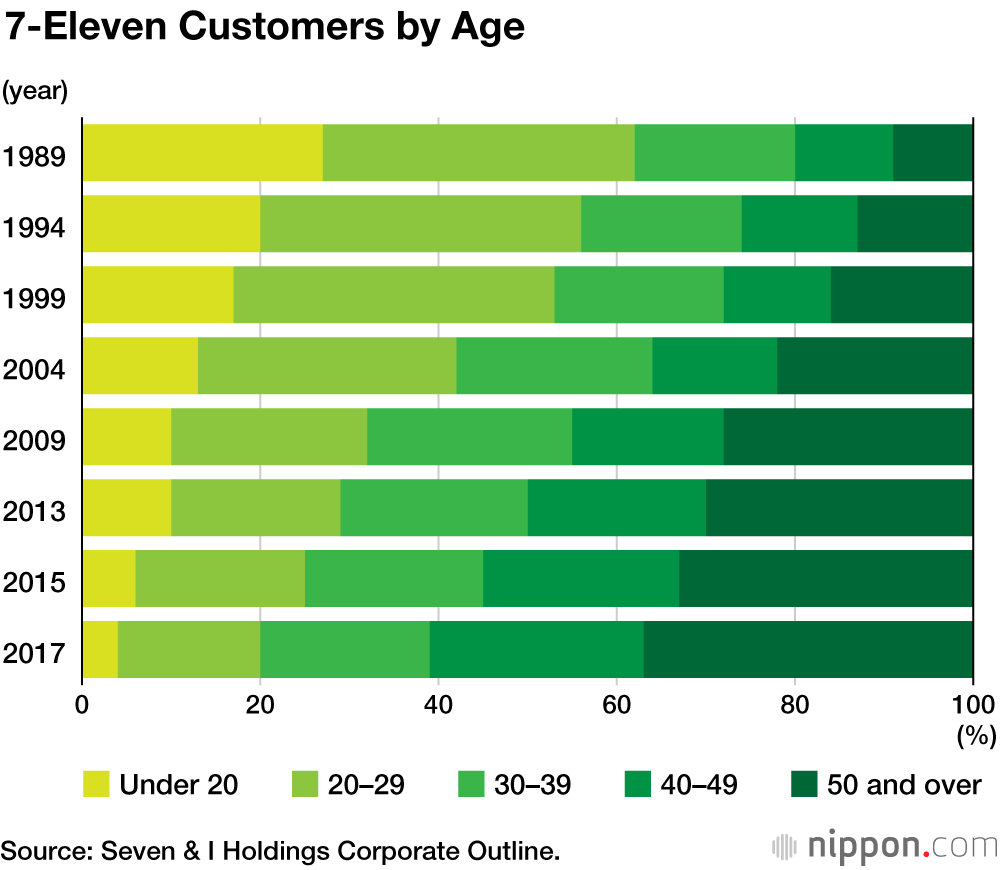

Over the last few decades stores have seen a demographic shift toward older customers. In 1989, 62% of people visiting Seven-Eleven stores were in their twenties or younger; by 2017 this figure had fallen to nearly 20%. During the same period, patrons aged 50 and older increased from 9% to 37%, a trend that is set to continue. As senior citizens typically do not go shopping late at night, the incentive is waning for stores to stay open at all hours.

Japan’s shift toward a super-aging society is partly behind the uptick in mean customer age, but uncertain financial times have also led younger consumers to tighten their purse strings. Young people today grapple with issues like increased nonregular employment and stagnant wages, not to mention the burden of propping up a social welfare system that, due to the nation’s meager birthrate, will see new recipients swell and workers paying into the scheme decrease.

Financial unpredictability, coupled with coming of age in an affluent society, has taught young Japanese to be shrewd consumers. They know how to take full advantage of buying options to get the best value for their money and avoid paying higher prices at convenience stores by shopping at discount stores or online.

At the same time, more senior citizens are living alone and turning to convenience stores for their daily shopping. According to the 2015 national census, the share of single-person households grew to more than 30%, of which a third were residents 65 or older. The ratio is set to increase further as people forego or postpone marriage and the nuclear family continues to be the dominant social unit.

Convenience stores are well adapted to serve the needs of lone seniors, as shops sell food and other products in small quantities and are typically located in residential areas, making them easy to walk to. However, while shops in dense urban areas might be able to stay open 24 hours a day, Japan’s rapidly aging regions are feeling the pinch of labor shortages, making the business model less sustainable overall.

Working couples are another group relying on convenience stores in greater numbers. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare’s 2018 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, both parents worked in around 60% of households with children under 18 years of age, and the ratio is expected to grow amid government efforts to have more women join the labor force. Convenience stores help cut the workload of busy parents, offering a wide selection of ready-to-eat foods that can reduce the time spent on cooking and cleaning up. However, couples are more likely to stop in on the way home from the office, further reducing the need for shops to remain open through the night.

A Vital Role to Play

There are most certainly still people who find value in convenience stores being open all night. But as consumer options increase, including online shops that can deliver goods the same day, and stores struggle to find staff, there seems little reason for the industry to stick with a model that has value for a narrowing consumer group.

As I mentioned above, though, convenience stores serve an infrastructure role in many rural communities with large elderly populations. Having no shops that are open around the clock is a concern for citizens in times of disaster. However, local authorities could address this issue by working with outlets to set up a rotating schedule similar to what some medical facilities in remote areas follow, guaranteeing that at least one shop is always open through the night. This would allow convenience stores to retain their role as lifelines in times of disaster while enabling businesses to reduce costs by trimming store hours.

Moving away from the 24-hour model will require chains to overhaul operations, ranging from how staff clean stores and stock shelves to the management of production lines and transport networks. A simplistic shortening of store hours will not do away with all the issues that the current 24-hour approach presents; firms must use this opportunity to take stock and revamp their business models to fit the shifting consumer environment.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 28, 2019. Banner photo: A 7-Eleven store in Adachi, Tokyo, closes for the night on March 22, 2019. The outlet was one of several that tested new store hours. © Jiji.)