A New Look at Japan’s Demographic Divide

Ideological Perception Gap: Data Analysis Reveals Left-Right Distinction Lost on Young Japanese Voters

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Is There a Political Generation Gap?

Discussions of the generation gap in Japanese politics most often focus on disparities in voter turnout. In the 2021 House of Representatives election, the turnout among voters in their twenties was roughly half that of those in their sixties—36.5% as compared with 71.5%. Senior citizens are more numerous to begin with in Japan’s aged society, and with the disparity in turnout further augmenting their electoral presence, many pundits have deplored Japan’s “silver democracy,” in which the views of the elderly carry more weight than those of the younger generations.

Of course, this assumes that young people in Japan are politically at odds with their elders, but there is surprisingly little data to support that premise. My own empirical research into voter attitudes on key policy issues calls into question the assumption of a generational opinion gap. Other scholars (such as Osaka University Professor Kikkawa Tōru) have made the case that the correlation between age and social attitudes among the Japanese is disappearing.

Where the young and the old do seem to differ, however, is in their perception of Japanese parties’ ideological orientation. My research has found a significant disparity in the way younger and older voters characterize each party, suggesting that they may also view the basic structure of political conflict in different terms.

The Clarity of Cold War Politics

For the first few decades after World War II, Japan’s political forces were clearly ranged along stark ideological lines. Unlike in the West, where partisan conflict has focused on economic policy, the central political issues in Japan were the Constitution and security policy. On the right were the hoshu (conservative) forces, which sought to revise the pacifist postwar Constitution and to strengthen the (anticommunist) Japan-US alliance. On the left was the kakushin (progressive) camp, committed to preserving the war-renouncing Constitution and scrapping the Japan-US security arrangements.

In 1955, the hoshu forces merged into the Liberal Democratic Party, which was to hold onto power continuously until 1993. Under this “1955 system,” there was little disagreement as to the nature of Japan’s partisan divide: The ruling LDP represented hoshu ideology, while the opposition Japan Socialist Party and Japanese Communist Party embodied kakushin politics.

In the early 1990s, around the time the Cold War came to an end, a reformist coalition broke the LDP’s grip on power, signaling the collapse of the 1955 system. The next two decades were a period of ongoing partisan realignment. Yet while the term “liberal” gained some currency as a replacement for kakushin, the majority of voters continued to view Japanese politics as a struggle between hoshu and kakushin over security and the Constitution, with the LDP at one pole and the JCP at the other.

Tracking the Shift in Perception

Today, only about half of Japanese voters view domestic politics in these terms.

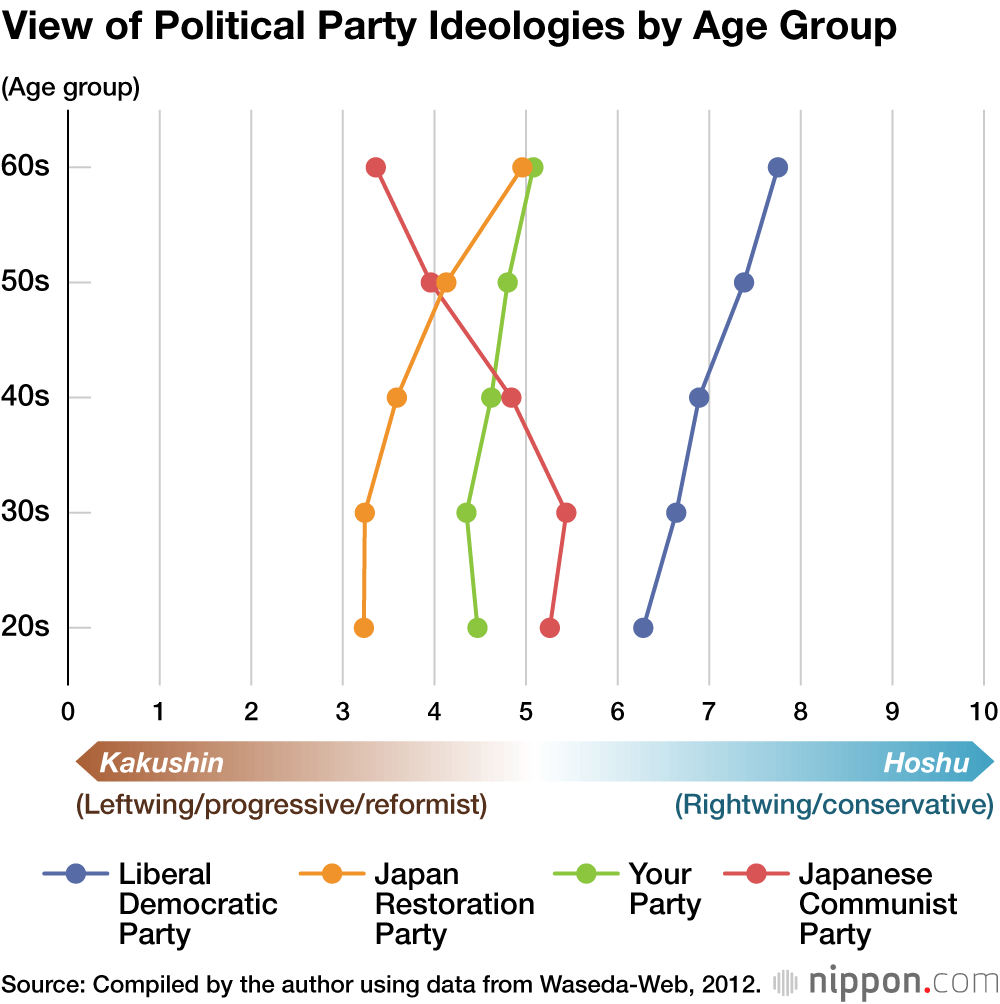

Since the 1980s, researchers in political science have been conducting surveys that ask respondents to characterize parties ideologically by scoring them on an 11-point kakushin-hoshu scale, with 0 representing the kakushin end of the spectrum, 10 the hoshu extreme, and 5 the middle of the road. The results, when disaggregated by age group, reveal a fascinating trend, apparent in the results of a web-based survey conducted shortly after the general election of 2012.

The accompanying figure charts those results for five parties: the LDP; the newly formed Japan Restoration Party (Nippon Ishin no Kai); Your Party (Minna no Tō), formed in 2009; and the JCP. The horizontal axis represents the kakushin-hoshu scale, while the vertical axis shows the age group of respondents.

Among respondents in their 60s, the LDP received an average rating of 7.8, placing it solidly on the hoshu side of the spectrum, while the JCP got a rating of 3.4, putting it unmistakably on the kakushin side. This result is consistent with the conventional characterization of the two parties, as is their considerable distance from one another on the ideological spectrum. This basic schema holds for respondents in their 50s, although their average scores place both parties a bit closer to the center.

However, when we come to the ratings of those in their forties and younger, the shift becomes more pronounced. Most significantly, the JCP moves toward the midpoint and beyond, ending up on the right-hand side of the spectrum among respondents younger than 40. The JRP (characterized by most analysts as a rightwing populist party), is situated far to the left of the JCP. What this suggests is that many voters in their forties and younger are equating the conflict between hoshu and kakushin with the rivalry between the LDP and the JRP, indicating a marked change in voters’ perception of Japan’s political battle lines.

Of course, this is just one web-based opinion poll. But shortly afterward, a group of researchers at Tsukuba University conducted a similar questionnaire by mail and got essentially the same results. Moreover, in another mail-based survey carried out jointly by the Yomiuri Shimbun and Waseda University just before the 2017 general election, the same trend was apparent, even when the term kakushin was replaced by “liberal.”

Some may be inclined to greet these surprising results by lamenting the political illiteracy of Japanese youth. But let us recall that the phenomenon extends to voters who were in their forties at the time of the survey. In fact, the results suggest that upwards of 40% of Japanese voters share this “twisted” view of the political parties and their ideological orientation.

Political Socialization in the Post–Cold War Era

How, then, to account for the perception gap? One key to the riddle may be the timing of “political socialization,” the process by which individuals’ political values and perceptions are formed through social interaction. Most people’s political attitudes take shape during the years from adolescence to early adulthood, after which they remain fairly stable. The environment and events to which one is exposed in one’s teens and early twenties can thus have a major impact on one’s lifelong political perceptions.

Japanese voters who were in their forties during the 2010s were coming of age politically in the late eighties and early nineties, around the end of the Cold War. In terms of international relations, the ideological struggle between communism and capitalism was becoming irrelevant. Domestically, the dream of a grand coalition of kakushin forces was fading rapidly. Young people undergoing political socialization during this period were far less exposed to ideological doctrine and debate than previous generations, which could account in part for the perceptual disconnect seen in the aforementioned surveys.

Related to this dynamic is the fact that the parties’ ideological differences were less clearly distinguishable after the collapse of the 1955 system in 1993. This was partly due to the partisan fluidity of the 1990s, when parties were continually splintering off, merging, and splitting again. But an even more important factor was the convergence of policies in response to the new electoral system for the House of Representatives, adopted in 1994, which introduced single-member constituencies in place of the old multiseat districts. A system in which only one candidate can win puts pressure on all the parties to shift their policies toward the center in hopes of capturing a majority. This convergence may have made voters less receptive to the established ideological classification of parties.

To be clear, this “twisted” perception of the partisan battle lines in Japanese politics is not a sudden or recent development. It has been taking hold gradually for more than three decades now. Much of what we were hearing from pundits, scholars, and the parties themselves remained grounded in the old ideological framework. But the percentage of voters who shared that view of politics was dwindling, quietly eroding the basic premise of political discourse.

Reform as the Keyword

How, then, do younger voters understand today’s partisan rivalries? The research conducted by my team suggests that they differentiate the parties not by conventional ideological labels but by their orientation toward reform.

Reform has been a persistent theme in Japanese politics since the 1990s. First came the electoral reforms that followed the LDP’s fall from power. This was followed by administrative reform, decentralization reform, and “the Koizumi structural reforms” of the early 2000s. Within this political environment, younger voters came to view the focus of partisan conflict as the struggle between reform and the political status quo.

The ideological battle lines between the parties have sharpened since the second administration of Abe Shinzō (2012–20), and election reporting has become more ideologically oriented as well. But to understand voter behavior today, reporters, analysts, and politicians need to acknowledge the existence of an age-based political perception gap and recognize the limitations of discourse premised on the ideological conflicts of a bygone era.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Party leaders assemble for a public debate at the Japan National Press Club, Tokyo, on June 21, 2022, ahead of the July 10 House of Councillors election; from left, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio of the Liberal Democratic Party, Yamaguchi Natsuo of Kōmeitō, Shii Kazuo of the Japanese Communist Party, Yamamoto Tarō of Reiwa Shinsengumi, and Tachibana Takashi of NHK Party. © Jiji.)