From the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, Japan was a source of modern learning for China. It was also the “cradle of the revolution,” providing a place of refuge for numerous exiles. It was in this context that the Xinhai Revolution broke out in 1911. With international politics in disarray, Japan was to play a complex and diverse role as events unfolded.

Japan-China Relations in the 19th Century

During the Edo period (1603–1868), trade and other contacts between Japan and the outside world were strictly controlled by the Tokugawa shogunate. In addition to the officially sanctioned trade with China and the Netherlands that passed through the port of Nagasaki, the Tsushima domain conducted trade with Korea and the Satsuma domain with the Ryūkyū Islands and with Fuzhou in southern China. The northern Matsumae domain also traded with the Qing Dynasty via the Ainu and Tungusic peoples.

In China, trade with neighboring countries was carried out under China’s ancient tributary system, and the government permitted limited commerce with Western countries through the port of Guangzhou (the Canton trade). In addition, private merchants in certain coastal cities were permitted to trade with other Asian countries.

Trade relations between Japan and Qing-dynasty China opened up in the late seventeenth century after the surrender of the Ming loyalist Zheng government on Taiwan. For the next 170 years or so, Chinese merchants visited Nagasaki and traded with the Japanese. Through these resident Nagasaki traders—numbering in the thousands at their peak—China imported Japanese copper and marine products, while the Japanese imported sugar, as well as various cultural and luxury goods.

This situation changed in both countries around the middle of the nineteenth century. China’s defeat in the Opium Wars and pressure from the Western powers forced the Qing government to open additional ports besides Guangzhou to trade with the West. Similarly, Japan was forced to open Nagasaki and other ports to foreign shipping in 1859. Chinese merchants spread quickly from Nagasaki to Kobe, Yokohama, Hakodate, and other coastal cities and began to export local marine products and other goods directly to China. The port authorities in Nagasaki and Hakodate also began looking for ways to ship Japanese goods directly to Shanghai without relying on Chinese and Western intermediaries. Indeed, this was the original mission of the Senzai Maru, on which the Chōshū samurai Takasugi Shinsaku traveled to Shanghai in 1862.

In 1868 the Meiji Restoration set Japan on the road to becoming East Asia’s first modern state. In 1871 Japan and China concluded the Sino-Japanese Friendship and Trade Treaty. This was the first equal treaty between the two countries, but both the negotiation process and the outcome testified to China’s position of strength. Although the Meiji Restoration eventually came to be seen as a resounding success, at the time China and Korea regarded radical change on this scale as a recipe for chaos. Japan’s new government was looked on with skepticism until at least 1880, after it had crushed the Satsuma Rebellion and implemented the Matsukata financial reforms. China also held a decisive advantage over Japan in terms of naval power—at least as late as the second half of the 1880s. Japan’s position of weakness vis-à-vis China in these early years can be seen clearly in its diplomatic response to the 1886 riot by Chinese sailors in Nagasaki.

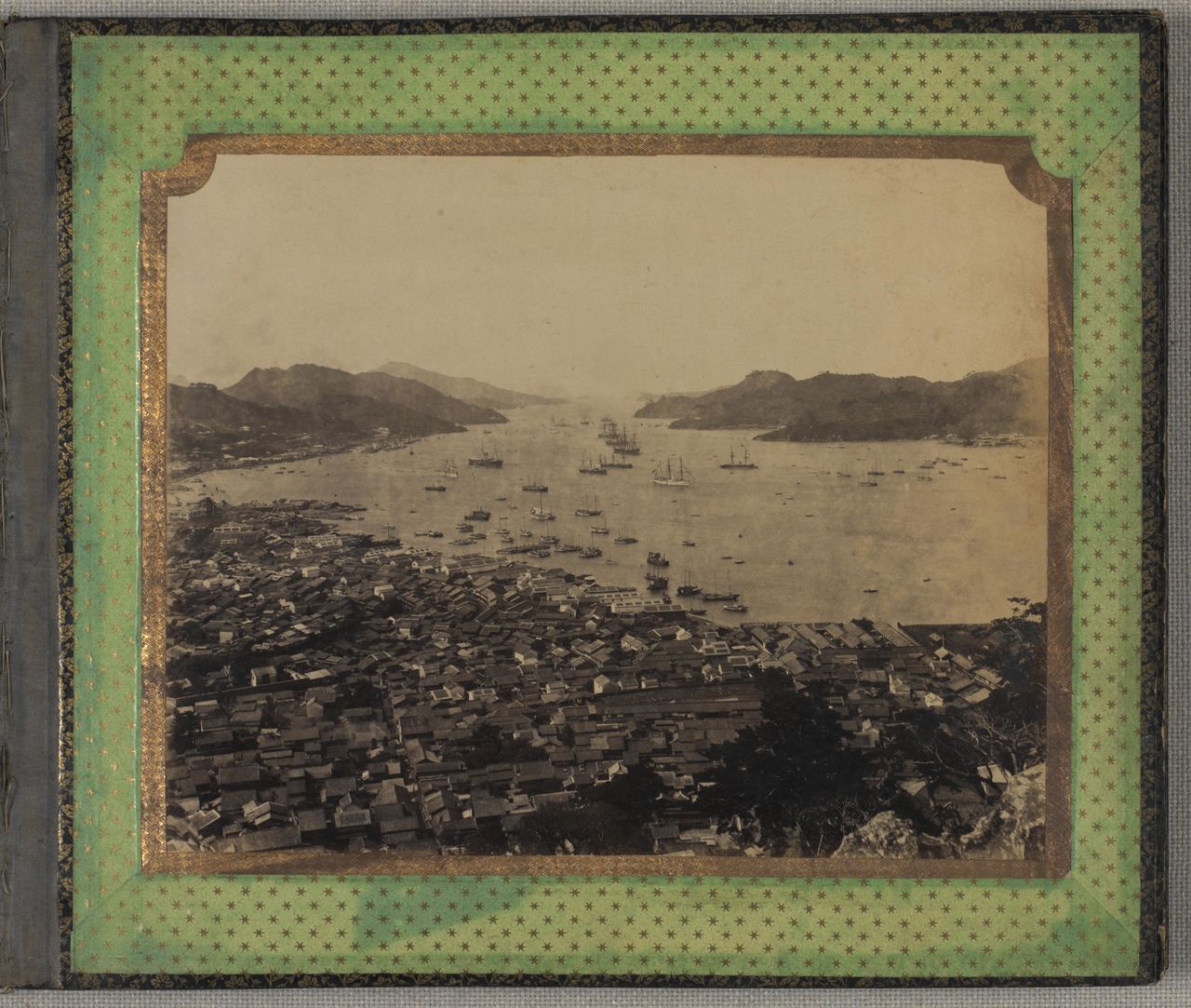

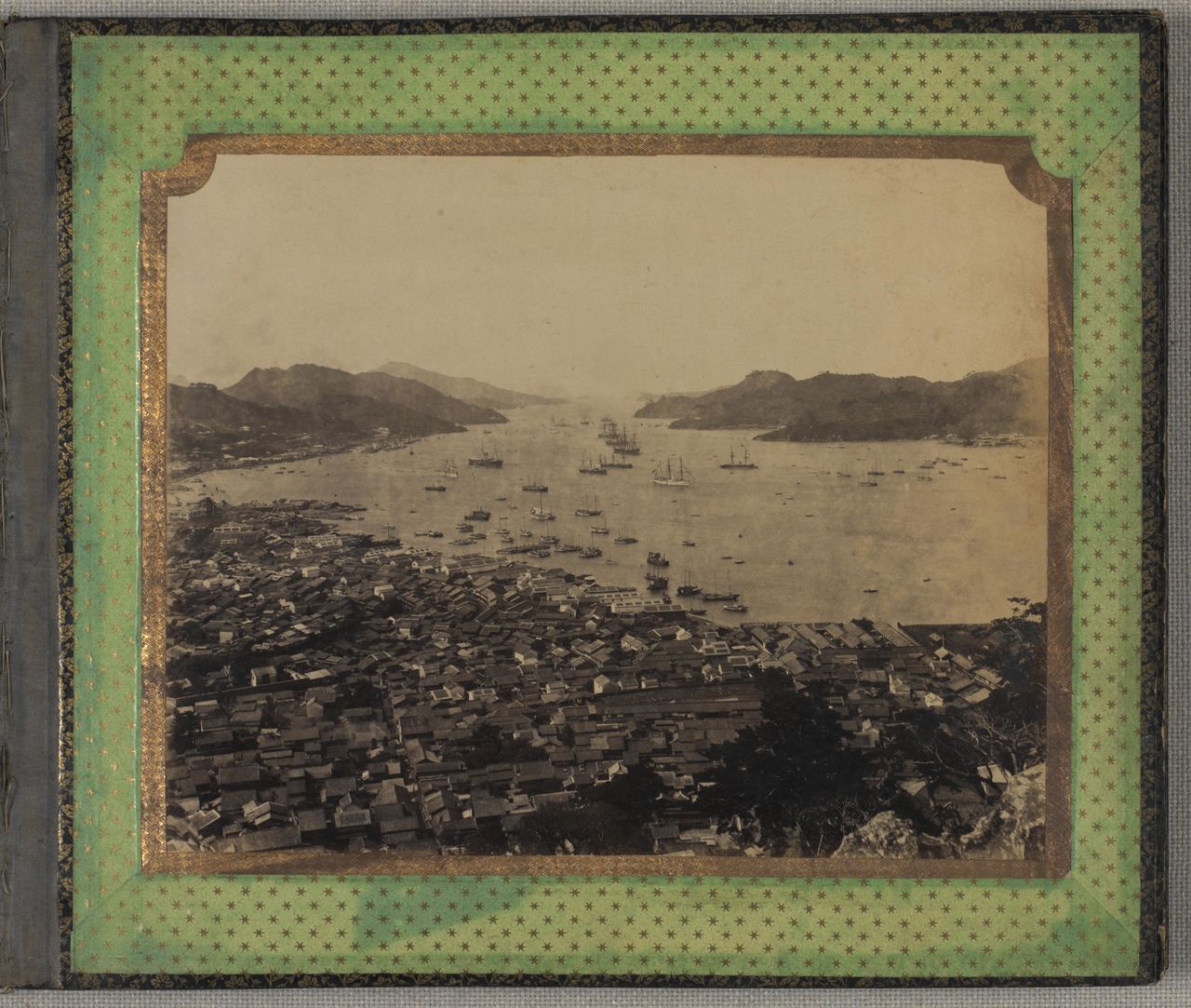

Nagasaki port during the Meiji era (Photo: Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture)

All this changed after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–5. Japan’s victory allowed it to take possession of Taiwan and secure economic and territorial concessions on a par with those forced on China by the Western powers. The first Sino-Japanese War also marked a turning point in Japanese attitudes toward China. Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu’s assessment of the conflict as a war between the modern (Japan) and the traditional (China) was typical of the symbolic significance that victory held for many Japanese, who increasingly tended to feel that their country was now superior to China. In China, meanwhile, Japan’s victory prompted calls for a new, modern government along the lines of the one established by the Meiji Restoration.

Seeking Modern Knowledge in Japan

Much of the knowledge that Japan selectively absorbed from the West during the Meiji era (1868–1912) was passed on to China via books and through the many young Chinese who came to Japan to study. This is not to say that “modern learning” did not enter China directly from the West. Nevertheless, the information that reached the Chinese via Japan had a particularly strong impact. For example, many of the character compounds used in Chinese today for concepts like “revolution,” “society,” and “economy” were borrowed from Japanese. The terms may have their roots in the ancient Chinese classics, but it was Japanese scholars who revived these archaic terms and gave them their modern meanings.

Chiang Kai-shek at the time he was serving in the Takada regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army. (Photo: Taiwan

Chiang Kai-shek at the time he was serving in the Takada regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army. (Photo: Taiwan

How these Chinese students felt about Japan itself, however, was perhaps a different matter. Although the language, with its quaint sprinkling of archaic terms most Chinese would only have previously have encountered in the ancient classics, may have been familiar and reassuring, alien customs like eating raw eggs and naked communal bathing no doubt inspired disgust. Nonetheless, Japan provided relatively easy access to the knowledge and know-how China needed to modernize.

Even the Qing court found something to emulate in Japan in the early years of the twentieth century, when a decision was taken to introduce a constitutional monarchy. The powers envisioned for the Chinese emperor in the 1908 Qinding xianfa dagang, which outlined the principles for an imperial constitution, were clearly modeled on those given to the Japanese emperor under the Meiji Constitution. Chinese students in Japan, meanwhile, were coming into contact with a much wider range of political ideas, including republicanism and socialism.

Political ideas were not the only thing Chinese students absorbed in Japan. Dozens of Chinese cadets traveled to Japan every year to study and train with the Imperial Army and Navy. Chinese alumni of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy fought on both sides when fighting broke out between revolutionary forces and the Qing army in the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. When the revolution broke out, Chiang Kai-shek himself was serving in the Takada regiment of the Niigata Army; he rushed back to China to join the rebels as soon as word reached him of the Wuchang Uprising in 1911. As all this suggests, Japan played a vital role in this period as a conduit of information and ideas about the modern state and society—including ideas about political reform and revolution.

Incubator of Revolution

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, political exiles gravitated to Japan from countries all around Asia, especially China. Although Chinese rebels and dissidents could also seek refuge in the released territories and foreign concessions on China’s coast, they faced the risk of being handed over to authorities or killed by assassins as long as they remained on Chinese soil. The safest option was to go abroad—and neighboring Japan was an obvious choice. Nagasaki in particular served as a popular bolt-hole from Shanghai. As well as a regular mail service by sea, the laying of a submarine telegraph cable made it possible to get the latest news from China almost instantly. From nearby Japan, Chinese exiles could continue to organize, disseminate information, and raise funds for the cause back home. Although carefully watched by the Japanese authorities—who compiled voluminous reports on their activities—they were rarely detained or handed over to the Qing government.

Sun Yat-sen is a perfect case in point. Unlike Chiang Kai-shek and Zhou Enlai, Sun was never a student in Japan. Nevertheless, it was an important base for him during his years of exile. Japan was key to Sun’s growing reputation throughout East Asia. The Kyūshū Nippō (published by the Kyūshū-based ultranationalist society Gen’yōsha) made a major contribution in this regard when it carried a Japanese translation by Miyazaki Tōten of “Kidnapped in London,” Sun’s English-language account of his detention at the Chinese legation in London in 1896 (an incident that made him famous overnight in the West). Miyazaki’s memoir Sanjūsannen no yume (Thirty-Three-Year Dream), translated into Chinese as Sun I-hsien (Sun Yat-sen), further cemented Sun’s iconic stature in East Asia.

Miyazaki Tōten (Photo: National Diet Library)

Miyazaki Tōten (Photo: National Diet Library)

In 1905, Sun formed the revolutionary Zhongguo Tongmeng Hui (Chinese United League) in Tokyo and began publicizing his cause through its magazine, the Min Bao (People’s Journal). Information and propaganda published from Japan formed an important part of his revolutionary activities. Immediately after the Xinhai Revolution he returned home to become provisional president of the Republic of China.Sun fled to Japan again in 1913, after his successor Yuan Shikai successfully suppressed the “Second Revolution” sparked by his suppression of the National Assembly, and particularly the assassination of Song Jiaoren [Sung Chiao-jen], the young leader of the Kuomintang. He used Japan as his base for the next few years. (It was during this period that Sun married his third wife, the famous Song Qingling [Sung Ching-ling].) Proximity to China, a relatively low cost of living, good access to information, and a longstanding Chinese community of merchants and students made Japan an ideal refuge for Chinese activists.

The Xinhai Revolution: A Reality Check

Japan was thus intimately linked to the dynamism of Chinese politics at the time. Apart from Japan’s role as a source of information and a base of activity, though, what role did it play in the birth of the Chinese republic? In order to untangle this complex issue, we need to briefly review the events of the Xinhai Revolution and its aftermath.

Yuan Shikai (photo from John Stuart Thomson, China Revolutionized, Indianapolis: Bobs-Merrill Company, 1913.)

On October 10, 1911, revolutionary elements in the provincial army staged a coup against local authorities in the city of Wuchang in Hubei province. Following suit, other provinces, mostly south of the Yangtze River, declared their independence from the Qing government, joining together to establish the Republic of China in January 1912. Negotiations between the Qing court and the new government ended with the abdication of the last Qing emperor in February 1912. This marked the end of China’s 2,000-year-old monarchy and the birth of a new state founded on the republican model.

But the republican government was short-lived. Although Yuan Shikai, Sun’s successor as provisional president, initially agreed in principle to the idea of republican government, he objected strongly to the powers given the National Assembly under the Chinese Provisional Constitution of 1912. When the Kuomintang emerged as the top parliamentary party in 1913, its young leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated, presumably on Yuan’s orders. Popular opposition to the regime quickly mounted in China, but Japan and the Western powers continued to support Yuan, providing him with loans and according diplomatic recognition to the Republic of China upon his installation as full president. (The United States had recognized the new government earlier, when the National Assembly was convened.)

Although the Xinhai Revolution is often regarded as Sun Yat-sen’s revolution, its causes were complex, and went beyond the revolutionary activities of Sun and his supporters. One key factor was the tense relationship between the highly centralized Qing government and the provinces. These tensions came to a head in 1911 over the government’s plans to nationalize the railways while leaving much of their construction and operation to foreign companies (partly to enable the government to pay off its massive war indemnities). Secondly, there was also a widespread backlash against the Qing court’s plans to introduce constitutional government, which would have preserved the dynasty and maintained the supremacy of the Manchus in China. This alienated many who would otherwise have supported a constitutional monarchy and paved the way for a powerful coalition of anti-Qing forces. Third, a critical role was played by activists who worked to secure supporters among the provincial elite and the military along the Yangtze River valley and succeeded in translating this support into an actual uprising in Wuchang.

Against this background of confluent factors, a consensus emerged in favor of overthrowing the Qing, and the court was forced to cede power. Nonetheless, the territory of the Qing remained intact under the new banner “five races under one union,” and the court was allowed to retain some of the outward trappings of prestige, with the emperor continuing to live in the Forbidden City and the imperial family granted special status. Moreover, the subsequent transfer of power to Yuan Shikai, a former imperial general, made the change of government look more like an orderly succession than a revolution.

Mixed Feelings in Japan

Coming so soon after the High Treason Incident, a 1910 plot to assassinate the Japanese emperor, the collapse of imperial rule in China inevitably sent shockwaves through the Meiji government. Public sentiment was somewhat more sympathetic, but still decidedly mixed. In their travel diary Pari yori (From Paris), the poet Yosano Akiko and her husband Yosano Tekkan described Shanghai as they saw it when they visited immediately after the Xinhai Revolution: “The so-called revolutionary army, having had the good fortune to rise up at a time when insiders and outsiders alike were completely fed up with the Beijing government, appears to be emerging, however improbably, as the dominant force. In terms of real ability to govern, however, the impression it conveys is of a rabble of people, on a par with the Kagoshima samurai-school students during the Seinan Rebellion in 1877, who are simply running about making a commotion.” Former Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu expressed an even more dismissive view in the November 1911 issue of the monthly magazine Chūō Kōron: “Sun? Why bother commenting on someone like Sun? Besides, I’ve had it with revolutionaries. Obviously there's nothing special about Sun.” The philosopher and critic Miyake Setsurei offered a more guarded assessment in the same publication: “Only time will tell whether Sun emerges as a great man or ends up as a nobody.” At this point, at least, while Sun remained in exile, the Japanese were by no means unanimous in their support of him.

Umeya Shōkichi and his wife Toku with Sun Yat-sen (Photo property of Kosaka Ayano)

Umeya Shōkichi and his wife Toku with Sun Yat-sen (Photo property of Kosaka Ayano)

That Sun Yat-sen’s revolution enjoyed the support of numerous Japanese Pan-Asianists is well known. Miyazaki Tōten and his brother Yazō, the brothers Yamada Yoshimasa and Junzaburō, Kayano Nagatomo, Tōyama Mitsuru, Inukai Tsuyoshi, Umeya Shōkichi, were among many enthusiastic supporters of the revolution in Japan. Sun himself acknowledged Japanese support for the revolution in his Jian guo fang lue (Overall Plan for National Development). Even today, this revolutionary partnership is cited as symbolic of the bonds of friendship between China and Japan. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the basic policy of the Japanese government at the time was to support the Qing court at Beijing. The majority of Japanese business interests also hoped for gradual political change and saw no reason to offer their support to a revolution that threatened to disrupt economic activity.

But what is more significant in this context is that in spite of the mainstream attitude of the Japanese government and business world, substantial numbers of people in Japan nevertheless chose to engage with China on their own terms and, out of their own inclinations and convictions, lent their support to a movement that began as an minority of outnumbered reformers and revolutionaries. This diversity was an important aspect of Japan-China relations.

Following the Xinhai Revolution, Sun Yat-sen’s popularity in Japan rose steadily. He benefited from his image as a “tragic hero” persecuted by Yuan Shikai and later from the position bestowed on him by the Nationalist government as “Father of the Revolution” and “Father of the Nation.” The Wang Jingwei [Wang Ching-wei] regime that Japan installed in Nanjing in 1940 also looked up to Sun as a founding father, while the popularity of the revolutionary view of history in postwar Japanese academic circles also did his reputation no harm. It is not uncommon for posterity’s view of historical figures to differ from contemporary assessments.

The Revolution’s Limited Impact

The truth is that the Xinhai Revolution did not dramatically alter China’s relationship with the Western powers and Japan. Since the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), the basic policy of the foreign powers had been to recognize the concessions each had secured by the late 1890s, while providing the Chinese government with loans to keep it afloat and preserve a stable environment for trade and commerce. Having no wish for chaos in China, the powers basically supported the Qing government.

It was Britain that brokered a peace settlement between the revolutionary forces and the Qing court as the delegates from the newly independent southern provinces formed a new government in Nanjing. It was also Britain, along with the other powers, that insisted that the new government be led by a “strongman.” Their choice for the job was none other than Yuan Shikai, a prominent general and official of the Qing court. In addition to controlling the Beiyang Army—considered the strongest military force in China—Yuan had the backing of pro-modernization Qing bureaucrats. When Yuan took over from Sun as provisional president, the foreign powers supported him and showered him with loans.

It is likely that Sun Yat-sen initially hoped to use the revolution to rectify the unequal treaties signed by the Qing government once and for all. In the end, however, the fledgling government calculated that it could not afford to antagonize the foreign powers, depending as it did on their recognition and loans. As a result, the Republic of China inherited the treaties signed by the Qing without alterations.

Heavily dependent on Qing bureaucrats, Yuan Shikai established his government in the Zhongnanhai compound in Beijing, where the Empress Dowager Cixi had formerly resided. The abdication of the Qing emperor brought about by the Xinhai Revolution was a tremendously important event in Chinese history. Nevertheless, this event did not immediately change Chinese politics, society, or the economy in any dramatic way. The revolution’s impact was quite limited on foreign and internal affairs alike.

The Turning Point in Japan-China Relations

Although Yuan Shikai, supported by the world powers, including Japan, initially went along with the republican system laid down in the provisional constitution, he was concerned about the establishment of a strong national assembly that threatened to limit the powers of the president. The assassination of Song Jiaoren [Sung Chiao-jen] and Yuan Shikai’s suppression of the Kuomintang-controlled National Assembly led to another uprising, known as the Second Revolution. Yuan and his supporters grew increasingly critical of Japan, perceiving widespread sympathy for the rebels among the Japanese people. Tensions were such that Japanese nationals in Nanjing came under attack by counterrevolutionary forces led by Zhang Xun [Chang Hsun].

After suppressing the Second Revolution in the fall of 1913, Yuan continued to cement his own presidential authority and curtail the powers of the National Assembly. In 1915, he declared himself emperor, triggering massive opposition and another revolt. Ultimately the embattled Yuan abandoned his claim to the imperial throne and died in disappointment in 1916.

Ōkuma Shigenobu (Photo: National Diet Library)

Ōkuma Shigenobu (Photo: National Diet Library)

The period of Yuan Shikai’s rule, from 1912 to 1916, marked the critical turning point in relations between China and Japan. Despite gathering support for the revolution among the Japanese public, the government and business had stood firm with the Western powers in supporting first the Qing government and then the government of Yuan Shikai. Then in 1915, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, the Japanese government under Ōkuma Shigenobu presented Yuan Shikai with the inflammatory Twenty-One Demands, a unilateral act that angered the Western powers and elicited a violent backlash from the Chinese people. When it became known that the Chinese government had capitulated to the Japanese demands, public opinion in China turned decisively against Yuan and against Japan. From this point on, all efforts to restore Japan-China relations to a friendlier footing were doomed to failure. The Twenty-One Demands became a symbol of imperialist aggression in China, and Japan became the number one target for Chinese nationalist ire.

(Originally written in Japanese.)