Kobe 1995 and Tōhoku 2011 were both earthquake disasters, but the first saw most deaths from fires and collapsed homes, while the second was a complex disaster involving a tsunami and nuclear power plant meltdowns. Former director of the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office Ōmori Yoshio considers Japan’s crisis management in the light of these two events.

Major earthquakes are nothing out of the ordinary in Japan. Niigata, Miyagi, Hokkaidō, and Tottori are just a few of the places that have been struck by sizeable quakes in recent years alone. But the first in living memory that was on a scale sufficient to call into question the nation’s political ability to cope was the magnitude 7.3 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, which devastated the city of Kobe and surrounding areas in January 1995, causing more than 6,400 fatalities. I was working in the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office at the time, as part of the coalition government of the Liberal Democratic Party, Japan Socialist Party, and New Party Sakigake headed by Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi. In what follows, I want to take a look at the government’s response to the March 11, 2011, disaster in the light of my experiences following the 1995 Hanshin quake.

Despite superficial similarities, the two events were in fact quite different in nature and scale. In the case of Hanshin, most of the damage was caused by the earthquake itself and the fires that followed. But the Tōhoku earthquake was a multiple disaster. The magnitude 9.0 earthquake and massive tsunami were followed by the nuclear crisis in Fukushima, whose effects included radiation contamination of agricultural products and seafood. Badly shaken consumer confidence has had a baneful knock-on effect on tourism and industry.

Three Fundamental Changes

Before moving on to an evaluation of the government’s reaction to the crisis, I want to touch on three fundamental changes that have taken place in Japanese society in the 16 years since the Hanshin earthquake. These are: dramatic improvements in terms of telecommunications technology and infrastructure; the increasing importance of convenience stores at the center of daily life; and the growing impact of globalization, which now makes its influence felt in people’s everyday lives.

Let us consider telecommunications first. Remarkable progress has been made in the field of video transmission. When the Hanshin earthquake hit, all the local transmission centers, including those belonging to fire departments and NHK, the quasi-national broadcaster, were put out of commission. This meant that all transmissions from the disaster area were temporarily interrupted. This, combined with the fact that the earthquake struck at 5:46 ᴀᴍ on a Tuesday after a three-day weekend, meant that although reports reached the prime minister’s office that an earthquake had taken place, it was some time before anyone realized just how serious the situation was. The Tōhoku disaster was different. It took place at 2:46 on a Friday afternoon, for one thing, and video footage and other information from the scene was available almost immediately. The vastly improved communications infrastructure, with multiple lines now in place to prevent any interruption to transmissions, came into its own. Without these improvements in technology, it would have been impossible for the prime minister’s office to take command and issue instructions. Maintaining contact with the numerous individuals and authorities involved would have been out of the question. A secure and reliable communications system was also vital for dialogue and close cooperation between ministries and local governments and crucial for the swift and large-scale deployment of the Self-Defense Forces, which I will return to later.

The Urgent Need to Secure Communications

Japan has some of the highest penetration rates in the world for both fixed-line and mobile telephones. But fixed and mobile networks were overwhelmed for some time immediately after the disaster, and for several hours very few calls were getting through. In the future, improvements will be needed to bring line capacity up to date with an age in which mobile phone penetration is 100% or more. We also need to develop a framework to ensure priority for emergency calls to police and fire departments from mobiles and Internet phones when communications are down after a disaster.

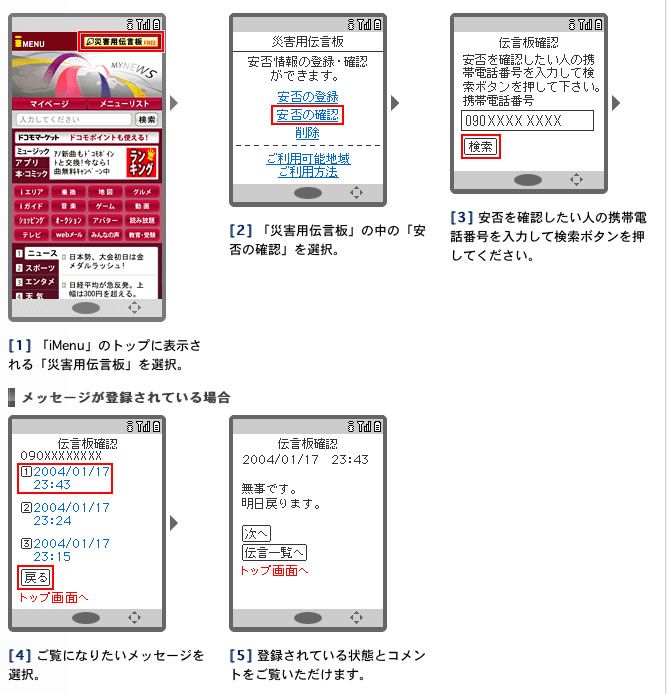

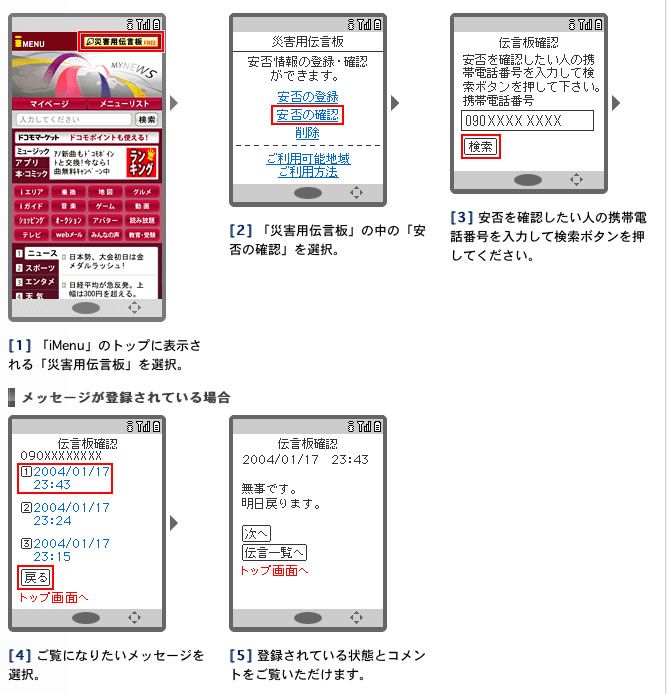

When major quakes or other serious disasters strike, residents in the afflicted areas can report their safety to friends and relatives via message boards carried on mobile phone networks. (Images: NTT DoCoMo.)

Another important lesson to emerge from the disaster was the indispensability of Twitter and other social networking services as robust communication tools when phone lines are down. The disaster boards and messaging services provided by communication companies were particularly effective in the days after the disaster, allowing people to post messages to let friends and family know they were safe. Google’s Person Finder service, launched just two hours after the disaster, provided a database of names and other information compiled from various evacuation centers and disaster mobile phone message boards. More software like this for use in emergencies is certain to be developed as a matter of priority in the years to come.

Twitter and similar communication tools proved invaluable in terms of getting details about the latest situation to the public and providing updates on what emergency relief supplies were required. The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) was just one of several important players to use Twitter extensively following the disaster, along with central and regional government offices, volunteers and journalists in the disaster areas. Although Twitter and similar services were undoubtedly extremely effective ways of making information available, unfortunately a “digital divide” meant that the elderly and others without access to these services were at a considerable disadvantage.

Unfortunately, several instances of scaremongering in the days and weeks following the disaster also revealed a major downside to digital communications channels that allow any user to broadcast indiscriminately. Some of these were political; others were groundless rumors tastelessly dressed up as efforts to help. Several times, groundless reports spread via Twitter claiming that “hundreds of people are stranded in such-and-such a municipality . . .” These false rumors wasted valuable time and resources, and may even have cost lives.

Convenience Stores at the Center of Daily Life

Convenience store operators began sales from mobile truck-based shops in mid-April. (Photo: Kuyama Shiromasa.)

The trucks were fully stocked with food, drink, and other necessities for daily life. (Photo: Kuyama Shiromasa.)

The growing importance of convenience stores in people’s daily lives was already attracting attention as a social phenomenon around the time of the 1995 Hanshin earthquake. Ideally located at the heart of daily life and providing immediate necessities such as food, drink, information (via radios and computers), and public lavatories, convenience stores have replaced citizens’ centers and community police boxes as places of refuge in times of disaster for millions of people in contemporary Japan.

The nationwide chains demonstrated their formidable organizational strengths in the days after the disaster, mobilizing national networks to send urgently needed supplies of food and other necessities to the disaster areas around the clock. Even more impressive were the dedication and hard work shown by store managers and employees (including part-time staff) in places where store premises had been destroyed and stock either destroyed or thrown into disarray. Amid the chaos, employees set up temporary retail spaces from which to provide customers with the supplies they needed, despite the losses that many managers and employees had suffered at home. The same remarkable levels of service were seen right across the board, and were not restricted to any particular chain or any individual area. No doubt these impressive results are testimony to the effectiveness of the each company’s ongoing training and employee education programs—but they would not have been possible without the efforts and performance of people on the ground, from the store managers on down. This pattern—of people coming together to produce results under a local leader—is one that is seen throughout Japanese history. Tsuchiya Motohiro, a professor at Keiō University, has compared this sociological phenomenon to the biological concept of emergence, in which ants and termites work together to construct remarkably complex nests by performing a sequence of simple actions without any obvious overall guidance from a strong leader. In the past, conventional crisis management was premised on the American model, which sought to consolidate the necessary information together in one place before implementing a response under strong executive leadership. But the judgment and sense of responsibility of each individual is one of the strengths of Japanese society. In this sense, giving initiative and responsibility to workers on the ground is an effective approach in times of emergency. It represents a division of labor in which the central headquarters takes charge of overall strategy and education while teams of workers on the scene contribute greater local focus.

The Growing Internationalization of Life in Japan

Another thing the recent disaster made abundantly clear was the extent to which daily life in Japan has become internationalized since the Hanshin earthquake 16 years ago.

For many years now, Japan has been a major donor of aid in the aftermath of natural disasters around the world, but this time the aid was flowing in the opposite direction. Since March 11, as many as 150 countries have offered assistance, and rescue teams from around the world began to arrive in Japan within days of the disaster. On the other hand, many foreign businesspeople, trainees, and workers flew home after March 11, leaving the streets looking emptier than normal and having a significant impact on business and manufacturing.

Several foreigners lost their lives or were badly injured in the disaster. More than ever, we were made painfully aware of the ongoing need to provide information for foreign nationals who might be particularly vulnerable in the event of disasters and to provide evacuation instructions in foreign languages.

Another thing that has become clear is the need for a change in the way the government and important bodies like TEPCO make information available to the public. In the past, announcements and press conferences have been based on question-and-answer sessions in Japanese for Japanese journalists. This is no longer good enough. Joint statements based on studies carried out with the cooperation of international bodies such as the International Atomic Energy Agency are essential for ensuring that the international community has an accurate understanding of the situation. We need to reflect seriously on where we have gone wrong in this respect. A total rethinking is required of our frameworks for communicating information to people in Japan who do not speak Japanese, as well as the rest of the world.

The reality of Japan’s position as a member of the international community was brought home to people in their daily lives following the recent disaster. Mineral water was shipped in from Korea to boost dwindling supplies, and alkaline batteries were rushed in from Southeast Asia. At the same time, the impact of the disaster on the numerous sub-suppliers and component manufacturers in the Tōhoku region paralyzed the international supply chain. The impact of the disaster spread far and wide with remarkable speed, and auto factories around the world ground to a halt.

The disaster was a rude reminder of how vital reliable communications and shipping channels are in today’s “just-in-time” world, in which production has been streamlined on a global scale.

The Lack of an Emergency Act

Next, I want to discuss several factors that have not changed in the 16 years since the Hanshin disaster.

The first is the lack of any provision by the state (or in the Constitution) for special legislation that would apply in a state of emergency. In this respect, Japan forms a striking contrast with Germany. Following its defeat in World War II, Germany engaged in a national debate that lasted some 20 years before finally incorporating state of emergency legislation into its constitution. In Japan, by contrast, the lack of limitations on private property laws can slow down cleanup operations in an emergency situation, since even rubble is treated as private property. Even municipal rezoning and road-widening projects to make disaster areas safer can be brought to a standstill by an uncooperative property owner. Japan’s Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act does grant the prime minister certain prerogatives once a natural disaster emergency situation has been declared, such as the right to put limits on the prices of everyday necessities. But the government of Prime Minister Kan Naoto decided not to declare an emergency following the March disaster. The reasons for this decision are not clear, but as a result it proved impossible to make a dramatic shift from normality to a crisis footing.

However, even in Japan the system has begun to change in recent years, following the introduction of the Armed Attack Situation Response Law and the Civil Protection Law, which have beefed up the legal provisions for dealing with a defense-related national emergency. In its reluctance to mobilize emergency legislation in responding to the recent disaster, the government is likely to have been held back by the restraining influence of conventional interpretations of the Constitution. This led to the everyday, vertically compartmentalized administrative structure being carried over into the realm of emergency response, crippling the government’s chances of reacting speedily.

Insufficient Civilian Evacuation Standards

An October 2010 drill at the Hamaoka plant in Shizuoka Prefecture was based on the loss of power to the cooling systems. In May 2011, Prime Minister Kan requested that the plant be shut down based on the high likelihood of a major earthquake in the region (an 87% chance in the next 30 years, according to some data).

Nuclear power is the one major exception to Japan’s lack of civil emergency legislation. Following the lessons of the criticality accident in a uranium reprocessing facility at Tōkaimura in 1999, the Act on Special Measures Concerning Nuclear Emergency Preparedness was passed, granting the prime minister the authority to issue special orders in the event of a nuclear emergency. Following the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, the prime minister exercised this prerogative by declaring Japan’s first ever nuclear power emergency situation in accordance with this legislation. However, as subsequent events showed, the standards for evacuating local residents were unclear and as a result, a thorough evacuation proved impossible. It is hard to deny that legally speaking, Japan lacked the concrete regulations it needed to cope with a situation on this scale; on a practical level, there was a failure to follow through on the assumptions and training exercises carried out in advance. Prime Minister Kan apparently remembered nothing about a training exercise carried out last October based on a scenario in which cooling system power was lost at the Hamaoka Nuclear Power Station. That the person theoretically in overall charge should have forgotten all about this exercise speaks volumes about how complacent the authorities were in their preparations for an emergency.

Public Spirit and Community Feeling

Another thing that was unchanged since the Hanshin disaster was the remarkable Japanese sense of public spirit and commitment. Even the Chinese media, which often take a critical view of Japan, were full of admiration for the way in which people remained calm and maintained order. All around the world, images of Japan’s collected response to the disaster provided an opportunity for people to see the Japanese as they truly are, after years of biased education and reporting.

A video message from the emperor was broadcast five days after the disaster, moving people across the nation and inspiring fellow feeling in people from all walks of life. The impact of the emperor’s message right across Japanese society is testimony to the state of the nation at this time. The emperor’s considerate message encompassed words of kindness for disaster victims, gratitude for assistance from around the world, acknowledgement of the hard work done by the Self-Defense Forces and emergency services, and wishes for a speedy recovery. It was a perfectly pitched message that conveyed a strong sense of Japan’s cultural traditions.

More than 100,000 SDF troops from throughout the country came to Tōhoku to help by searching for the missing, clearing rubble, and feeding people living in shelters. (Photo: Ministry of Defense.)

People wait their turn in a temporary bath constructed by SDF members. (Photo from the Ministry of Defense.)

The institution that has made its presence felt more than any other since the disaster has been the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, which deployed more than 106,000 troops. After the Hanshin disaster, an inept initial response on the part of some local leaders meant that the government was slow to mobilize the Self-Defense Forces in the early stages of the disaster, leading to regrettable delays in relief work. This time, they mobilized swiftly and efficiently. These were the first ever joint operations of the land, sea, and air forces under the general command of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Forces North Eastern Army. This is likely to prove a landmark achievement.

There have been numerous reports of troops making light of their own hardships in order to pay their respects to the dead or provide hot meals and baths to survivors.

Public awareness of the role of the Self-Defense Forces has risen dramatically in the wake of the disaster. Rather than allowing the situation to peter out with no more lasting consequences than a few human-interest stories, I propose that we amend the law to allow the Self-Defense Forces to administer affairs within the disaster areas on a temporary basis. Steps like this will be necessary to restore order to the chaos that has prevailed in some areas since the disaster. In dealing with the nuclear contamination in Fukushima, we also need to ensure that our troops are equipped with the same standards of protective clothing, remote-control robots, and decontaminants as those issued to the US forces.

The Many Successes of Operation Tomodachi

US President Barack Obama was also quick to respond.

The US armed forces and SDF jointly launched Operation Tomodachi soon after the quake struck. Some 20 naval vessels, 160 aircraft, and 20,000 personnel took part in the operation. (Photo: US Pacific Fleet.)

Just five hours and 20 minutes after the disaster, the president made a statement to the effect that “the friendship and alliance between our two nations is unshakeable.” US Forces in Japan and Hawaii moved quickly. As part of Operation Tomodachi (named after the Japanese word for “friend”), US troops went to work fast, moving transporters and other heavy machinery into Sendai Airport and restoring the airport to a useable condition just days after it was swamped by the tsunami. Amphibious Essex-class assault ships were used to land marines on small adjacent islands to remove rubble and debris. It was the kind of contribution that only the US armed forces could have made.

Three Japan-US Bilateral Coordination Centers were set up in the Ministry of Defense, Yokota Air Base, and Sendai, where joint operations between US and Japanese forces were carried out for the first time. This should have a significant impact on Japan’s national security policy in terms of the message sent to neighboring countries.

But we cannot afford to be too optimistic in our assessment of Japan’s autonomous crisis management.

Almost as soon as reports began to suggest that a radiation leak had taken place at Fukushima, the United States dispatched RC-135 planes from Kadena in Okinawa and Global Hawk reconnaissance planes from Guam equipped with radiation-detection equipment. The measurements taken by these planes suggested that a core meltdown had taken place, and as a result the United States recommended its citizens to evacuate at least 80 kilometers from the power station.

Either because Japan lacked the ability to carry out the same kind of detailed observations or because of political mistakes on the part of the Kan government (the latter seems the likelier explanation), the American evaluation and response proved far more realistic than the Japanese government’s response, even though the accident took place in Japan and chiefly affected the lives of Japanese citizens. This should be a cause of considerable regret and reflection for the government.

The Political Leadership Masquerade

The Democratic Party of Japan government has bungled repeatedly in its response to the disaster. In particular, it has failed to collect information from administrative organizations in an appropriate manner, and the orders issued by the prime minister’s office under the name of political leadership have been nakedly opportunistic. Delays in issuing clear instructions, along with repeated corrections and amendments, have led to a fatal loss of credibility.

But perhaps the gravest problem lay with the mechanism for crisis management itself. One reason was the lack of any system to allow the government to take responsibility for supervising and overseeing nuclear power stations, and a lack of the necessary expertise that would have allowed the government to direct TEPCO more effectively. We need to learn from the example of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission and train specialist units in the Self-Defense Forces to take responsibility for nuclear power.

A second problem is that at present it is extremely difficult to make the transition from regular conditions to a state of emergency. As I note above, the lack of any provisions for special emergency powers in the Constitution lies at the heart of this problem. In order to avoid a repetition of the bitter experiences of the Hanshin earthquake 16 years ago, we need to have a national debate as a matter of urgency about giving the prime minister special rights and executive prerogatives in the event of a state of emergency.

The third problem was the lack of any appropriate venue for discussing the possibility of a nuclear accident. It was felt that introducing measures based on the assumption on a worst-case scenario would only spark anxiety. For this reason, the necessary measures were never introduced and the few people who warned of the dangers of nuclear power saw their arguments ignored or suppressed. Perhaps this cautious approach was prompted by consideration for Japanese sensitivity to nuclear issues after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the time for sentiment is over. Japan needs to take this opportunity to learn from the example of France and other countries. We need to make absolutely sure that there is no contradiction between the nuclear safety structure and our plans for an emergency response if and when the worst comes to pass.

(Originally written in Japanese.)