Depictions of Eros and Thanatos: Sacred Trees of Shintō Shrines Through the Lens of Ōsaka Hiroshi

Art Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Memories of Childhood

Giant, old-growth trees are infused with a powerful lifeforce that sustains them over their extensive lifetimes, which span centuries longer than that of humans. Some even say that they harbor sacred spirits.

Since earliest times, trees that grow in forests and on the grounds of Shintō shrines have been the object of worship as protective deities and as the spirits of the dead. Such trees have withstood vicissitudes in the weather and climate year after year and their forms have been molded by centuries of hardship. Some are twisted and gnarled and others have intertwined with other trees until they have become parasites living off each other. Many have grown old, wilted, and died, while others continue to grow, their leaves and branches seemingly stretching heavenward. Humans have interpreted the fates that have befallen trees variously as warnings or as sources of purification and courage.

I grew up in a poor, isolated village in the Tōhoku region in northeastern Japan. The village was in a mountainous area where the snow would pile up so high during the cold, harsh winters that we had to use the second-floor windows to get in and out of the house. If you went deeper into the nearby wilds, there was a thickly wooded and gloomy forest of giant trees. We lived in a house along a stream in a village where everyone made their living mining copper. The copper mine closed down when I was a little boy, and I remember holding my parents’ hands and walking fearfully along a narrow road as we left our village for good. On both sides of the road there was water—probably processed waste water—that pooled to form eerie bogs that glistened a greenish milky white. I still remember being afraid that if I should lose my footing I would be swallowed up by one of those bogs, which I imagined to be portals to the underworld. I don’t know how many times their otherworldly glow has since appeared in my dreams.

In my twenties an uncle of mine and I had the opportunity to visit the region where I spent my early years. The wild, mountainous land was overgrown with vegetation, underscoring the years that had passed. As we pushed through the tall grass and made our way along a trail that was revealed on the ground below, we eventually came to a spot that looked like it had once been occupied. Nearby there was a riverbed overgrown with weeds. The partial remains of stone walls were the only traces of the lives that people once led there.

“This must be where the village was,” my uncle said.

This place, where the sound of cicadas reverberates through the mountains in summertime, is where I was born. This is the place of my origin, this is where my life began. The fragments of my memories of this time began to take shape after my parents’ deaths and now seem to occupy the deepest parts of my being. I wondered if I could capture these memories in photographs. This is what led me to start on my series Jurei Junrei (Pilgrimage to Sacred Trees), in which I photographed giant trees throughout Japan.

Each One Unique

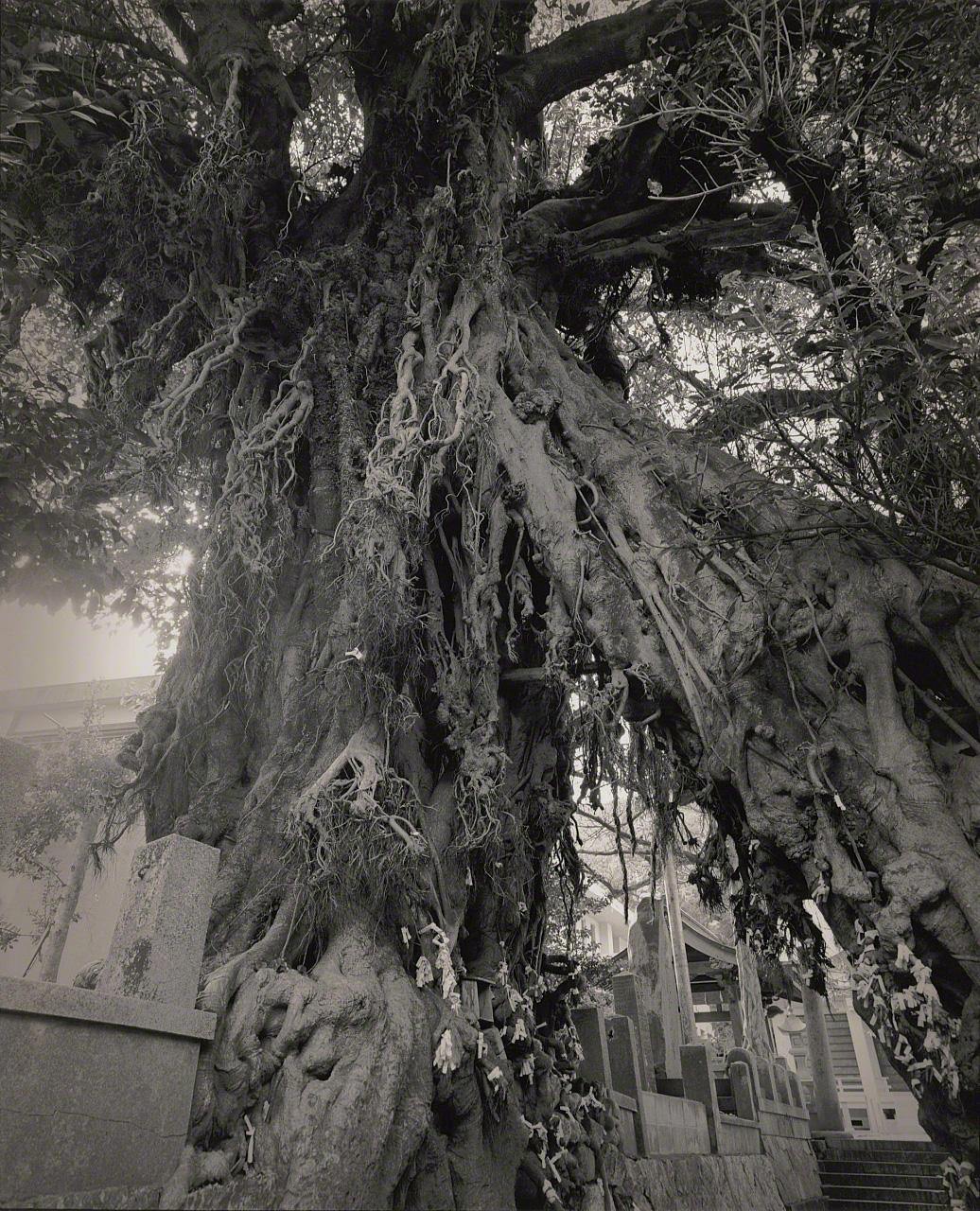

Photography has been my doorway to a wide variety of experiences, but there are several trees that have left a particularly strong impression on me. One is an akō tree (Ficus superba var. japonica) on Fukue in the Gotō Islands of Nagasaki Prefecture. This tree became intertwined with another tree as it grew and eventually overpowered the other and became the main trunk supporting them both. The two trees soared up into the sky, their trunks seeming to form two legs straddling the road leading to a Shintō shrine. The roots that spread out from the bases of these trees resembled the human nervous system, the complexity of which symbolized a lifeforce and sheer physical presence that overwhelms everything else in the vicinity. As I passed underneath the arch formed by the two trunks—as one must in order to continue to the shrine—a chill ran down my spine. The trees seemed to serve as gatekeepers that were there to prevent those with evil intent from advancing and to allow only the virtuous through.

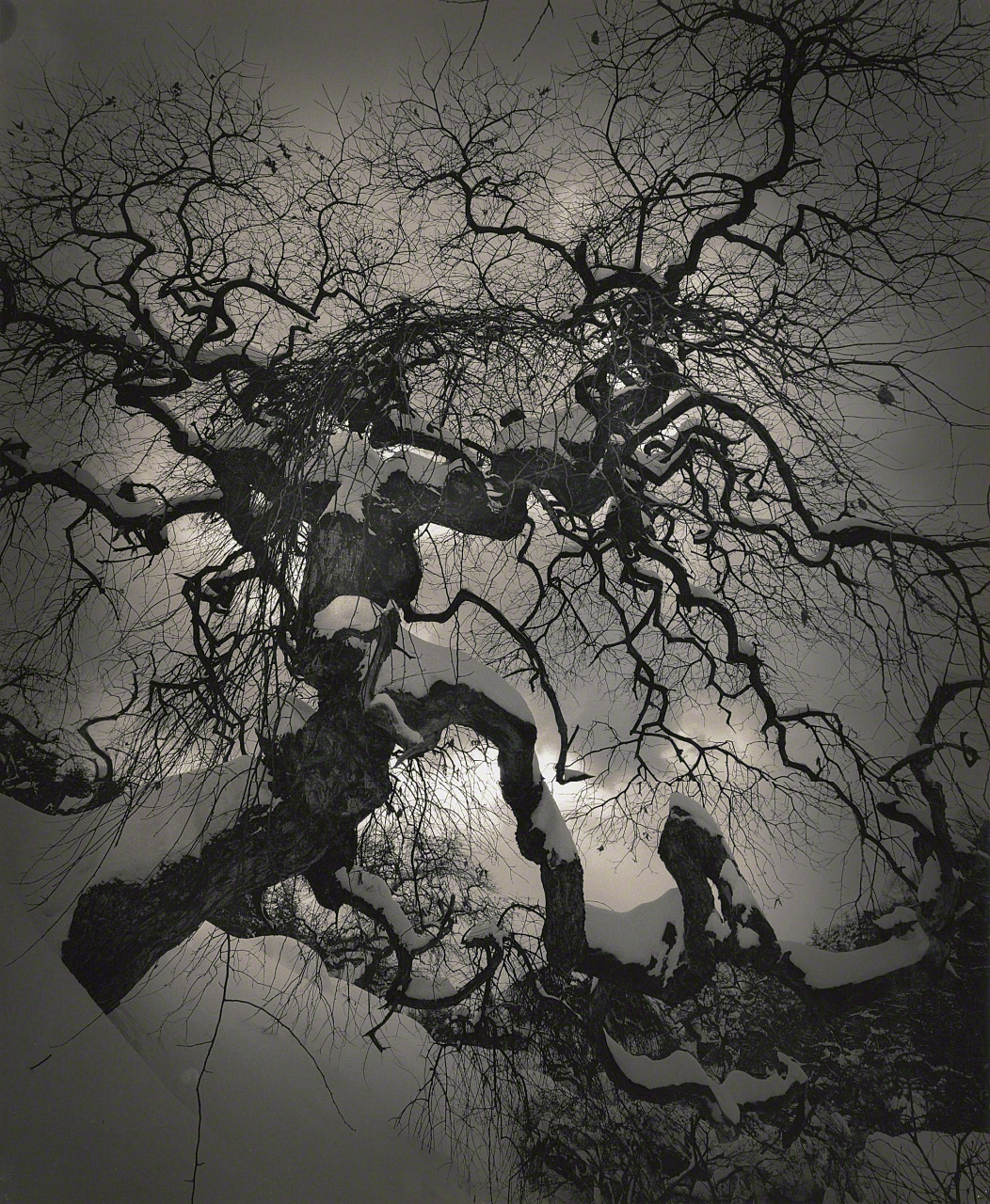

Another tree that left a strong impression on me is a weeping chestnut in the town of Tatsuno in Nagano Prefecture where I visited one winter. The drooping leafy branches spread out in spirals all around the tree making it seem as though it is sporting a permanent wave hairstyle. This gives the tree an aura of the weird and wicked that is quite off-putting. As the tree is located in a region that experiences heavy snowfall, there is no way to get there by car. I still remember the anticipation I felt as I walked for hours to see it.

Yet another example is a sacred ginkgo tree in Saitama Prefecture that is estimated to be over 700 years old and has a trunk measuring approximately eleven meters in circumference. Located on the serene grounds of a Buddhist temple that was built in an area carved out of the bedrock, its roots are partially visible above ground as they have encircled a large boulder. They present visitors with an extraordinary sight as they look like a thick entanglement of snakes.

From the branches and parts of the trunks of some of the trees hang what are known as “aerial roots,” which have the appearance of stalactites suspended from the ceiling of a cave. As some of these aerial roots resemble human breasts, some say that visitors will be blessed with safe deliveries and healthy children.

Reverence for the Trees

Not too long ago something inexplicable happened while I was photographing a hinoki (Japanese cypress) in Fukushima Prefecture with an 8x10 camera. I sensed the oppressive presence of something inhospitable emanating from the tree and I stopped what I was doing. A second later the feeling was gone and I set my camera up on my tripod. As it was hot, I took off my jacket and draped it over a nearby fence. As soon as I did this, the calm weather I had been enjoying up to that point was suddenly upended by the roar of a powerful gust of wind that swept in from the forest far beyond. The wind knocked down my tripod and camera, and several thick tree branches above my head fell to the ground with a loud crash. The entire area around me had become a windswept disaster in an instant and the hinoki I had been trying to photograph had been transformed into a disheveled wreck right before my eyes. What’s worse, I discovered that some of the metal components on my wood-body camera had bent when my tripod toppled over.

I then noticed a stone slab off to the side of the tree. The writing on the slab explained that this was a sacred tree in which are enshrined the spirits of dead military commanders from the Warring States period in Japanese history (1467–1568). I became fearful when it occurred to me that the sudden wind may have been the military commanders’ way of telling me that they didn’t want to be photographed, and I bowed and asked for their forgiveness. I was about to abandon my plans to photograph the tree when I noticed that my lens and shutter mechanism were undamaged. I made emergency repairs to my camera and took several photos of the tree in spite of the fact that it had had several of its branches violently shorn off in the wind.

These magnificent trees are overflowing with an evocative spirit that affects the mood and atmosphere of everything around them. Some are sacred trees that are hundreds of years old and some are ancient trees that have survived the harshest winters. Every time I photograph these trees I remind myself to respect and revere them, as I am thankful that they exist. When I lay my hands on their bark I feel their breath and their lifeforce pulsing through them, a lifeforce that they share with me every time I photograph them.

(Originally published in Japanese. Text and photos by Ōsaka Hiroshi. Banner photo: From the Jurei series.)