Diving Deep on Tuna to Uncover Surprising Variety

Guideto Japan

Food and Drink Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan Fifth in 2022 Total Catch

Tuna has become a standard part of sushi and sashimi menus all around the world under its Japanese name: maguro. Japan has developed a reputation as the world’s largest tuna consumer, but some in Japan fear that the fish’s throne is being threatened by the likes of salmon. While fish consumption around the world is growing, the fact that Japan’s is shrinking might simply be the course of nature.

Up through the 1980s, Japan was far and away the world’s leading fisher of tuna varieties, but when sushi became a popular overseas dish, it was overtaken by Taiwan and Southeast Asian nations, Mexico, and Spain. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Japan came in fifth in 2022 with an annual haul of 120,000 metric tons, about a third of the leader Indonesia’s 340,000.

Southern bluefin tuna being unloaded at Shizuoka Prefecture’s Shimizu Port. (Courtesy of Marushin Shōten)

Northern bluefin tuna continues to command premium prices in Japan and is a hit with overseas visitors here. Even so, the nation’s tuna market is unexpectedly diverse, with varieties like southern bluefin or bigeye tuna, as well as differences between wild caught or farm bred, domestic or imported, fresh or frozen.

Surprisingly, even maguro-loving Japanese consumers are relatively ill informed about the fish, and surely many diners—locals and tourists alike—simply see it all as “just tuna.” Here, I’ll go into the unique traits and fishing situation of each type to help readers better judge their fish of choice.

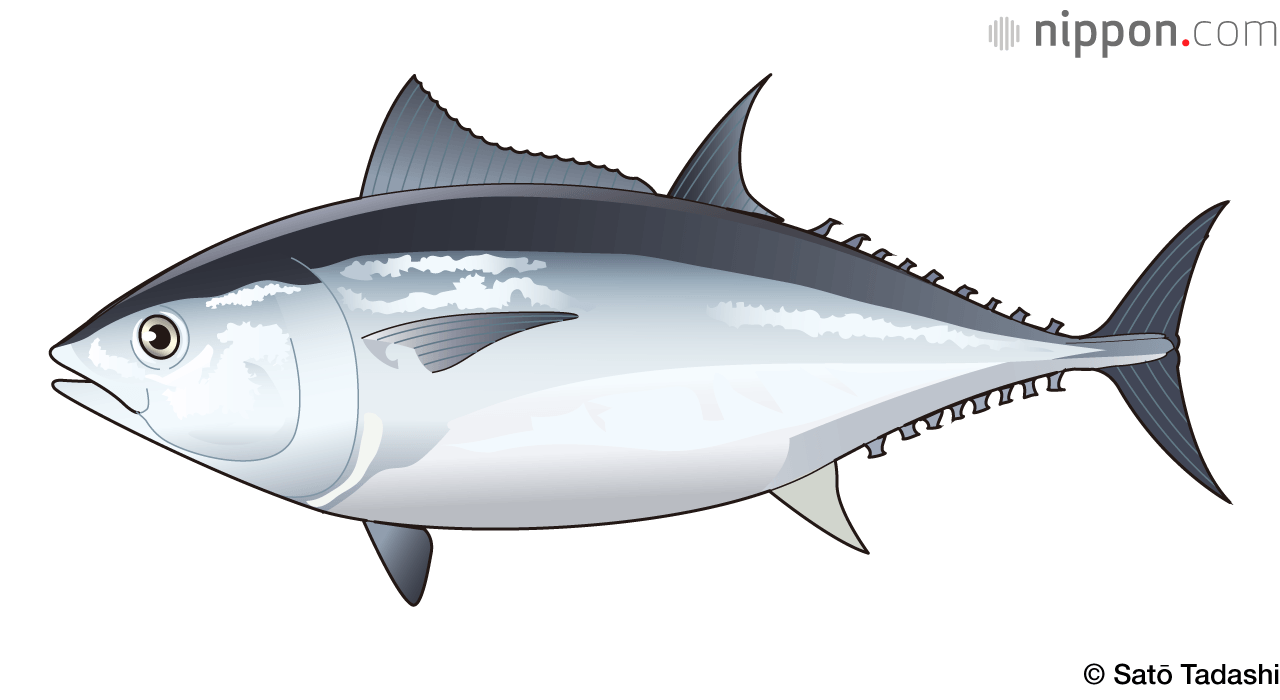

Northern Bluefin: The King from Local Waters

Northern bluefin tuna can grow up to 4 meters long and weigh in at over 400 kilograms.

First up is the king of all maguro, the northern bluefin tuna, or kuromaguro. Many industry insiders call it honmaguro, “true maguro,” marking it as the iconic ideal of tuna for consumers. Fishermen and market insiders often call it the “black diamond” because of the black luster of its scales and high prices it can bring. At the first wholesale auction of the year at Tokyo’s Toyosu fish market, a single fish can set records in the hundred-million-yen range, putting Toyosu at the center of the domestic tuna market. The coveted first tuna of the year sale went for 13 years straight to fish from Ōma, Aomori Prefecture, which now offers a globally known “brand” of Pacific bluefin, Ōma Maguro.

The northern bluefin swims in the coldest water of any tuna and grows particularly large, so it generates a lot of fatty meat. These fish live in both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, mostly in the northern hemisphere, and migrate through the waters along Japan’s coasts. The inshore catch, of which Ōma Maguro is the leading brand, can thus be sold unfrozen on the market. Even outside the peak sales season around the New Year holidays, it’s common for fresh honmaguro to fetch prices of over ¥10,000 per kilogram at Toyosu Market. Such meat can end up sold at high end sushi restaurants for several thousand yen a serving.

However, be careful not to equate the term kuromaguro with “fresh, inshore tuna.” Not only are some bluefin tuna farmed, some are shipped frozen from distant Pacific fishing grounds or even the Atlantic Ocean. Recent global resource management has set fishing quotas, and Pacific bluefin in particular has been tightly regulated, so inshore catch supplies are limited. According to Fisheries Agency figures, of the 61,800 tons of domestically supplied tuna in 2022, Pacific bluefin accounted for 10,000 tons, and that includes deep-sea fishing ships. That compares to over 20,000 tons of farmed fish, and around 25,000 tons of Atlantic bluefin.

Ōma Maguro sushi. At front right is ōtoro fatty tuna, back right is chūtoro medium fatty, and center is akami lean meat. (© Nippon.com)

Halved Quotas Stirring Up the Market

Recently, though, people have been expressing their hopes for more reasonable priced bluefin tuna.

In July 2024, the Northern Committee of the Western & Central Pacific Fisheries Commission held a meeting in Kushiro, Hokkaidō, where they agreed to increase Japan’s catch quotas. The quota for fish weighing in at 30 kilograms and over was raised 150%, from 5,614 tons to 8,421, while the small fish quota (under 30 kilograms) rose from 4,007 to 4,407 tons. That is the first increase for large bluefin tuna in three years, and the first ever for small fish. Under the understanding that small fish play a vital role in the future condition of fish stocks and determine the number of large fish later, there is also a chance that the large fish quotas could grow by over 150%, if the fishing situation is favorable next year.

Still, people related to the Fisheries Agency and fish markets are skeptical about the chances of prices falling. Japan’s fishing quotas are divvied up at the prefectural level and distributed further to various local fishery cooperatives, meaning they end up quite finely sliced, and it is never a given that any particular fishing ground will be fruitful enough to fill each individual quota. When it comes to the price of fresh, unfrozen tuna in particular, a wholesaler at Toyosu explained that it is largely decided by the haul of that given day or time, so it’s hard to say that an increase of a few tons over a whole year will result in any reduction in price.

At the very least, though, this quota expansion should not result in prices rising, so we can still hold out hope for reasonably priced tuna.

A fresh caught tuna from Japan’s leading maguro port, Katsuura in Wakayama Prefecture, auctioned off at Toyosu. (Courtesy of Toyosu Market staff.)

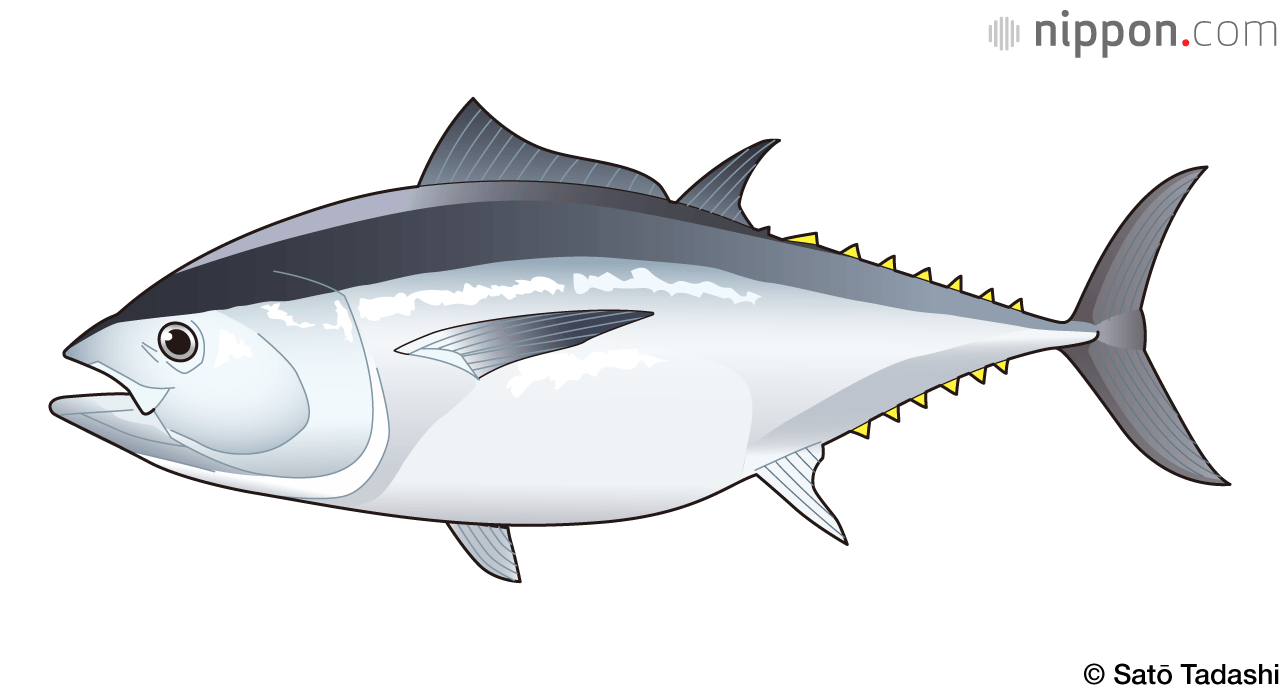

Southern Bluefin Prices Falling

Southern bluefin tuna reaches some 2 meters and around 100 kilograms.

The next highest rated maguro is southern bluefin tuna, which saw a sudden drastic fall in price this spring, putting fishermen in a quandary.

Southern bluefin is native to the Indian Ocean and other southern hemisphere waters and is often called “Indian” maguro in Japan. It has plenty of high quality, fatty toro and lean akami meat, making it a favorite with insiders at Toyosu. At times, it even earns more at auctions than northern bluefin. Market staff even say that the akami is sweeter and goes better with vinegared sushi rice, so even though northern bluefin is the overwhelming favorite, there are sushi chefs who much prefer Indian tuna.

A block of meat from southern bluefin tuna being sold at premium prices at a fish shop gearing up for the New Year holiday. (© Pixta)

Offshore tuna are caught by longline boats far out at sea and most are then shipped to market frozen. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in imports, and in fiscal 2022 there was a resulting rise in market prices for fish brought into domestic ports like Shizuoka’s Shimizu Port.

The level of stock in distribution recovered in fiscal 2023, though, and prices plummeted. According to the Japan Tuna Fisheries Cooperative Association, large (40 kilograms and over) southern bluefin tuna fell to around ¥1,500 per kilogram, a drop of 40% year on year. Because the fishing boats run in distant seas, they also suffer from rising fuel and material prices, as well as the dropping value of the yen. For the 75 or so ships the association runs, that has meant a drop in sales amounting to some ¥70 million per ship. “Most are now running in the red, and if this continues, fishing operations will become unsustainable,” says one association official.

The deep-sea fishing ships targeting southern bluefin also catch bigeye tuna, which live along the same fishing routes. If the number of southern bluefin fishing ships drops, then there will also be fewer of the more reasonably priced bigeye available on the market, and that will have a direct impact on household dinner tables.

Those on the supply side are hoping for a price recovery, but consumer understanding is an obstacle. Southern bluefin tuna has weaker brand power than northern bluefin, and customers seem to doubt that the warm southern seas can produce fish as delicious as cold northern waters. However, the truth is that the waters south of Australia or the Cape of Good Hope, meaning the very southern reaches of the Indian Ocean, produce fish that make the experts drool.

The association released a video promoting southern bluefin tuna at the end of June, in hopes of stimulating demand. It also plans to inform customers about the finer points of the fish’s flavor, offer recommended recipes, and continue sharing information to overcome the barriers.

Unloading frozen tuna at Shimizu Port. If the price of southern bluefin doesn’t rebound, there is a danger that both it and domestic bigeye will see a fall in supply. (© Pixta)

Bigeye: Maguro for the People

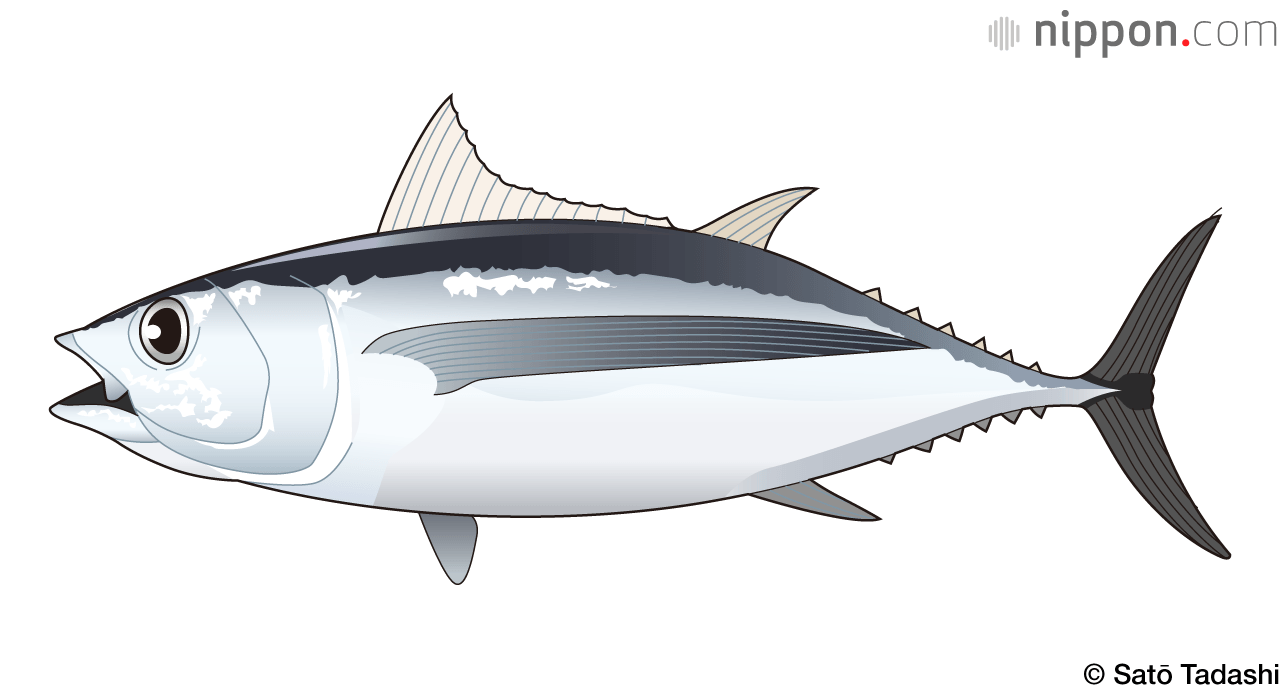

Bigeye tuna can reach up to 2 meters and exceed 120 kilograms.

Unlike premium northern or southern bluefin tuna, bigeye is a common sushi topping at conveyor belt sushi places or in supermarket coolers. As its name indicates, it has particularly large eyes, making it stand out from its blue finned brethren. There is no farmed bigeye, so all the meat that reaches the market is wild caught. Its vivid, lean akami meat is light but still packed with umami, making it easy to eat and an accessible treat for the common folk.

The often-seen supermarket bargain packs of “maguro odds and ends” are mostly bigeye tuna. (© Pixta)

In recent years, the domestic catch has stayed around 26,000 tons, but much more is imported from Taiwan, South Korea, and China. The total yearly distribution is almost 80,000 tons, outpacing the total 77,000 tons of northern and southern bluefin together. They are caught across wide swathes of both the Pacific and Atlantic, as well as the Indian Ocean near the equator. The vast majority reaches Japan frozen.

Until recently, fishing resource management only covered the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, but with catches in the Indian Ocean now also falling, this year saw regulations introduced there, as well. Many in the industry predict that it will not cause any significant reduction in catch, as the influence on distributed product and prices is limited, according to the leadership of the Japan Tuna Fisheries Cooperative Association.

Bigeye tuna caught in Australia. (Courtesy of Toyosu Market staff)

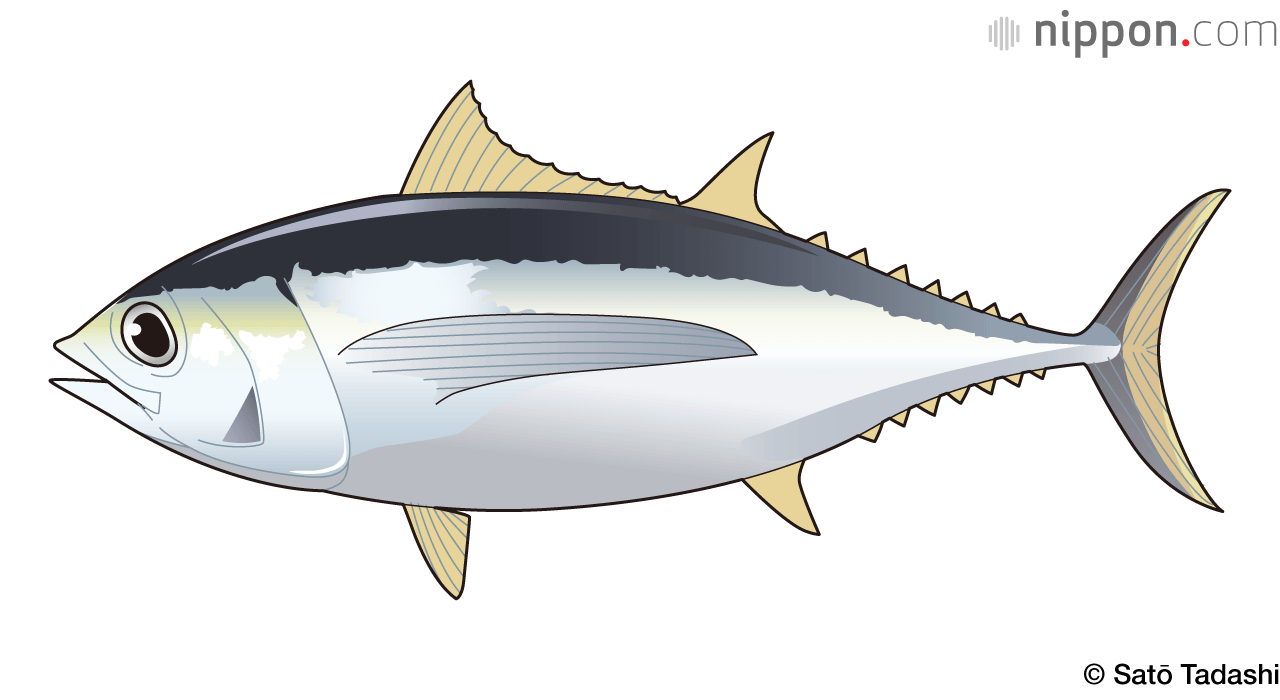

Yellowfin and Albacore: Light and Healthy

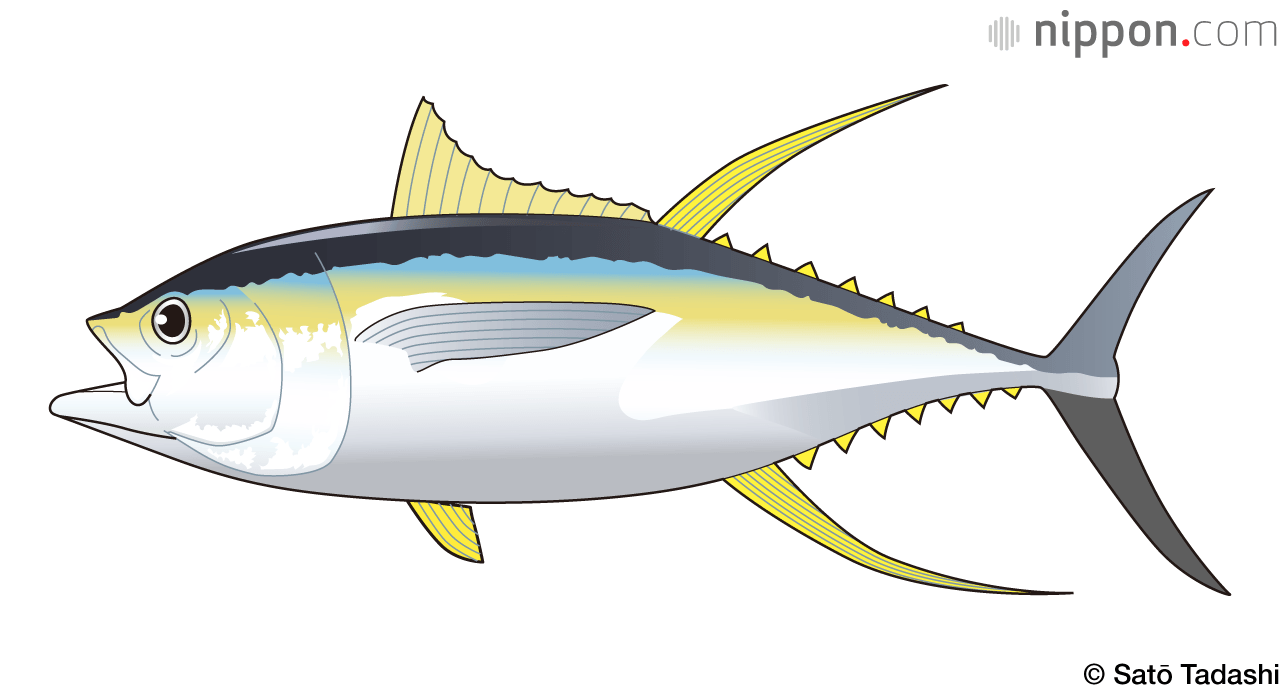

Yellowfin tuna, marked predictably by yellow coloration on their fins, can grow to nearly 2 meters and weigh between 70 and 80 kilograms.

Yellowfin is the domestic catch and import leader among all the tuna species. The yearly market supply in 2022 was 112,000 tons. The name comes from the yellow color of the long dorsal and belly fins, as well as along its sides. The meat is high in protein and has a delicate, subdued flavor. The chūtoro is popular for sushi, but the meat tends to have lower fat content, so it mostly ends up in cans of tuna.

The albacore tuna, with its long pectoral fins, grows to just over 1 meter and usually weighs in at around 40 kilograms.

The final tuna variety is the albacore, or binnaga maguro. The Japanese name binnaga uses the word for hair growing from the temples, because the long fins sweeping out from its side resemble sidelocks. The lean akami meat is pale pink and is a familiar sight at conveyor belt sushi under the name bintoro. The domestic catch is second to yellowfin, and it sells at reasonable prices. It is not only popular as sashimi, but in stewed or fried dishes, and like yellowfin, often ends up in cans.

Now, that you have a better grasp of each tuna’s unique character, you can call yourself a true maguro master and take your enjoyment of this tasty fish to the next level.

Albacore sashimi has a delicate pink color. (© Pixta)

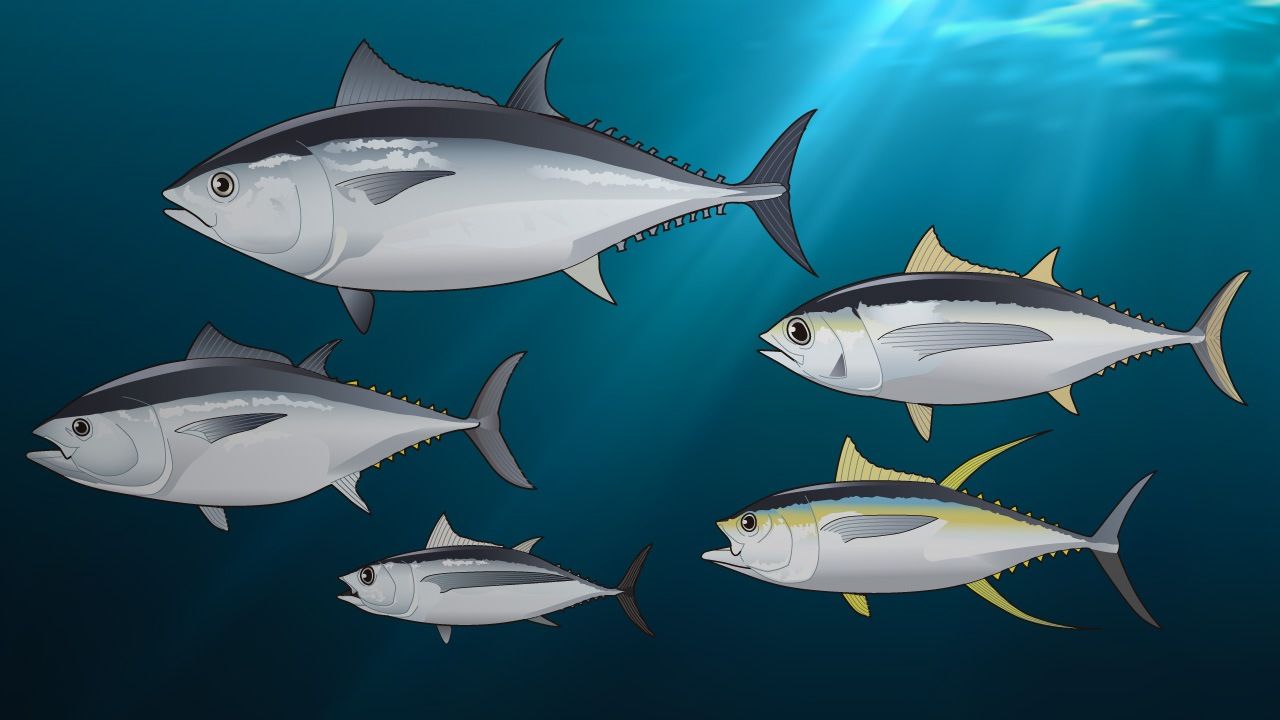

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A drawing showing the actual relative sizes of different types of tuna. © Satō Tadashi.)