The House that Shibusawa Eiichi Loved

Guideto Japan

History Architecture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Back to Its Roots in Kōtō

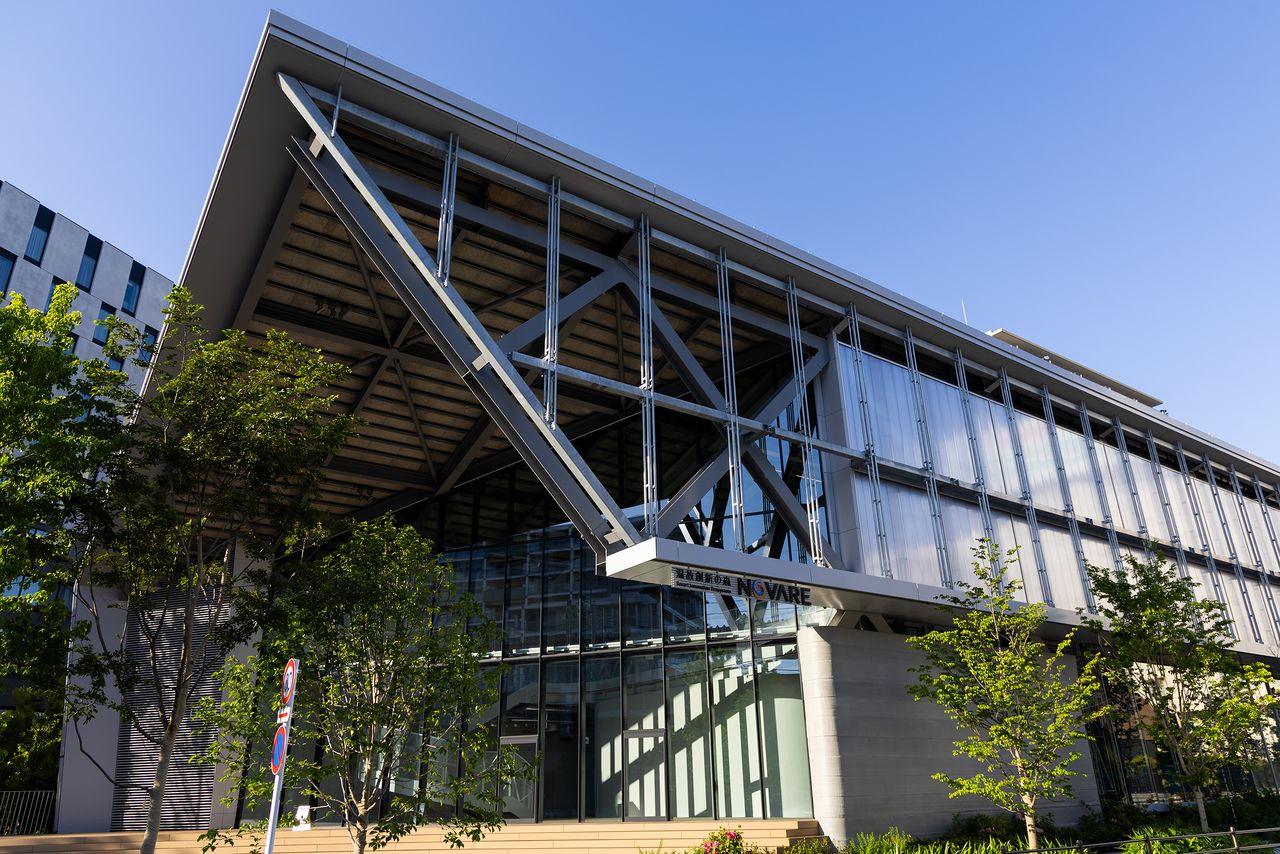

Walk out of the east exit of Shiomi Station on the JR Keiyō Line, and you see a stunning modern structure some 200 meters ahead, toward the Akebono-Kita Canal. This is the Novare Smart Innovation Ecosystem and human resources development complex erected by the construction giant Shimizu Corporation at a cost of 50 billion yen in the district of Shiomi in Kōtō, Tokyo. In the central open space along the building on the way to the canal stands a fine residence in the Wa-Yō setchū style fusing Western and Japanese design elements. At first glance, the structure seems out of place, but after a while it begins to look quite natural in its setting.

Novare Academy, a facility for training human resources and transmitting heritage technologies, stands northeast from Shiomi Station. (© Nippon.com)

From left to right, the complex consists of the Novare Academy, the Novare Hub, and the Novare Archives. The canal is further down the road. (© Nippon.com)

The traditional building on the site is the Former Shibusawa Residence, home of Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931), the man known as “the father of Japanese capitalism.” It was originally a Japanese-style house erected in 1878 in Fukagawa Fukuzumichō (today Eitai 2-chōme in Kōtō). After Eiichi moved to a new dwelling in Nihonbashi Kabutochō in 1888, it was occupied by his son Tokuji and Keizō, his grandson and the family heir. The house was relocated to Mita, Minato, in 1908, after which it underwent major expansion and the addition of Wa-Yō setchū elements.

After World War II, the house was given to the government as payment for a wealth tax. For a time, it was used as the Minister of Finance’s official residence and later as a venue for government ministry meetings. Sold to the private sector as surplus, it was relocated to the village of Rokunohe, Aomori Prefecture, in 1991. In 2018, the building passed into the hands of Shimizu Corporation, which began re-erecting it in Shiomi in 2020. With construction completed in 2023, the former residence finally returned to its original location 115 years later. Let us take a look at the house’s history.

The Former Shibusawa Residence consists of, from left to right, a Western-style wing, a main building, and living quarters for Keizō’s mother. The corridor connecting the Western-style wing and the main building is also in the fusion Wa-Yō setchū style. (© Nippon.com)

A faithful reproduction of Keizō’s study inside the Western-style portion of the house, based on early photographs. Panels displaying relevant materials have been installed. (© Nippon.com)

Stability After Footloose Years

Born in 1840 to a prosperous farming family in what is today Fukaya, Saitama Prefecture, Shibusawa Eiichi enjoyed a comfortable upbringing as the family heir. At the age of 21, he left for Edo (today’s Tokyo) to study and to learn swordsmanship, but fell into the life of a drifter.

A statue of a young Shibusawa Eiichi stands on the grounds of his former family home in Fukaya. (© Nippon.com)

Gradually developing ultranationalist leanings, Eiichi plotted to attack and burn down the foreign settlement in Yokohama. But the plan fell through and he fled to Kyoto in 1863, where he came under the protection of the household of Tokugawa Yoshinobu. When Yoshinobu was named shōgun in late 1866, Eiichi became a retainer and accompanied Yoshinobu’s brother Akitake to France. The shogunate fell while the party was in Europe on an inspection tour, and Eiichi returned to Japan in 1868. Living for a short time in Sunpu (present-day Shizuoka Prefecture), Yoshinobu’s family seat, Eiichi was singled out for his experience studying abroad and his outstanding capabilities and was soon invited back to Tokyo to join the new Meiji government.

Eiichi in his twenties lived in a whirlwind of contradictions and an ever-changing environment; he did not dwell in one place for long. Here was a young man who had plotted to overthrow the shogunate and expel foreigners from Japan. Yet he became a shogunate retainer, studied abroad, and ended up as an official of the Meiji government that deposed his patron, Yoshinobu. In this position he was thrown into the task of devising systems to bring the country into the modern age; perhaps as an extension of this, Eiichi became an entrepreneur, and the house he built in Fukagawa was the first home he knew as an adult.

Shibusawa City Place Eitai, a building housing the Shibusawa Warehouse Company’s head office and other businesses, stands on the first site of the Former Shibusawa Residence. A plaque standing in a small park along Eitai-dōri identifies the site. (© Nippon.com)

Abiding Affection for Fukagawa

Serving as finance minister in the Meiji government, Eiichi resigned that position in 1873, at the age of 33. He subsequently oversaw the First National Bank of Japan (today Mizuho Bank), which he had a hand in founding, and founded or managed a myriad of other firms.

Initially, he lived in rented quarters in Kabutochō, where the bank was located, but once that business got onto a firm footing, he purchased land and buildings on a site of nearly 10,000 square meters in Fukagawa and moved there. The First National Bank building, billed at the time as a masterpiece of pseudo-Western architecture, was even depicted in ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Eiichi commissioned its builder, Shimizu Kisuke of Shimizugumi, whose business later grew to be the present-day Shimizu Corporation, to build him a nearly 600-square-meter main house there. Set in verdant surroundings, the property even featured a salt-water inlet, Shioiri Pond, whose waters rose and fell with the tide.

The water feature modeled on the original Shioiri Pond complements the site beautifully. (© Nippon.com)

A guest room on the second floor of the main building boasts a decorative pillar masterfully carved by Shimizu Kisuke. (© Nippon.com)

The main building’s staircase is constructed of black persimmon and other rare woods. (© Nippon.com)

Eiichi lived in Fukagawa for 12 years. He next resided in a splendid Western-style mansion in Kabutochō designed by Tatsuno Kingo (1854–1919), the architect responsible for designing many of Japan’s earliest Western-style structures. In his last years, Eiichi made his home in Asukayama, a district in today’s Kita, Tokyo.

But even though Eiichi had moved to Kabutochō, he served as a Fukagawa local council member and later council head. When he lived at Asukayama, he was also chairman of the Fukagawa education council. And throughout his life, he maintained Fukagawa as his official registered residence. Given his deep feelings for the area, he must be pleased that his house has returned to its original location in Kōtō.

Eiichi in his later years. (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

Life at the Fukagawa House

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a wing on the east side was added to house Keizō’s mother, and other alterations were made to the house where Tokuji and Keizō lived. And in 1908, the structure was moved from Fukagawa to Mita.

A famous photograph depicts four generations of the Shibusawa family. Taken in 1925 when Keizō and his family returned from a posting in London, it shows Eiichi holding his great-grandson Masahide, a gentle smile on his face.

Eiichi dandles great-grandson Masahide on his knee, with his son Tokuji to his left and grandson Keizō standing center rear. (Courtesy Shibusawa Eiichi Memorial Foundation)

The photo was taken in this room on the first floor of the main building. (© Nippon.com)

In 1930, a Western-style wing had been added to the house standing in Mita, transforming it into its present distinctive blend of Western and Japanese architectural styles. Keizō and his family lived in that part of the house, which was filled with furniture and fittings offering sophisticated evidence of the family’s refined living style, tastes they had acquired during their time abroad.

There is an interesting story about the piano standing in the guest room. Made in 1922 by Bechstein, one of the world’s “big three” piano makers, it was completely reconditioned during the most recent rebuilding of the house. Purchase records at the company’s headquarters in Germany show that it was ordered by Mitsubishi.

The formal reception room on the first floor of the Western-style wing. The furniture, chandelier, and plaster ceiling motifs have all been faithfully reproduced. (© Nippon.com)

This Bechstein piano is a special-order model made for export to Asia. Its glued portions were reinforced with tacks to deal with the humid climate. (© Nippon.com)

Many historical novels and dramas depict Eiichi and Iwasaki Yatarō, founder of the Mitsubishi business conglomerate, as rivals who could not abide each other. But Eiichi’s grandson Keizō married Tokiko, the younger sister of a classmate of Keizō’s who was a granddaughter of Yatarō. The pair married in 1922, the year the piano was manufactured, so it may have been a wedding gift from the Iwasaki family.

Although Eiichi and Yatarō differed in their approaches to business, they respected each other’s acumen, and apparently Eiichi did not oppose his grandson’s marriage. And then there is the photo of a gently smiling Eiichi with Masahide, also a great-grandson of Yatarō, on his knee. The Former Shibusawa Residence offers this kind of historical background, which makes it all the more meaningful to history aficionados.

The stained-glass windows in the dining room were re-created based on two panes that had been preserved. (© Nippon.com)

Seismic reinforcement was added when the house was moved back to Kōtō. A new glass-walled elevator on the property offers a view of the steel frame and the diagonal braces strengthening the structure. (© Nippon.com)

Preserved for Posterity

Readers may wonder why the residence was moved to Aomori Prefecture at one point and later acquired by Shimizu Corporation. The house, which had been moved to Mita and used as a facility for government meetings, had become dilapidated and plans were afoot to demolish it. Sugimoto Yukio, president of Towada Tourism Development Co. at the time, offered to take it off the government’s hands. Sugimoto had been a houseboy in Eiichi’s time and later served as secretary and house steward to Keizō. After World War II, he moved to Towada, Aomori, where the Shibusawa family had a farm, and met success running hotels and developing an onsen hot spring.

Eiichi’s Kabutochō mansion had burned down in the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake, and his residence in Asukayama had been destroyed in wartime bombings. Only the Seien Bunko and the Bankōro structures remained standing there. To preserve the house where he had spent many years in service to the Shibusawa family, Sugimoto moved the residence far to the north of Honshū, to Shibusawa Park at Komaki Onsen, which he operated. However, his two businesses collapsed in 2004 and the house was eventually acquired by Shimizu Corporation.

The houseboy’s room by the entrance to the home, which Sugimoto presumably occupied while in service to the Shibusawas. (© Nippon.com)

To the Shimizugumi, Eiichi had not merely been a customer. When the third-generation head of Shimizugumi, Mitsunosuke, passed away suddenly in 1887, his son and successor was only eight years old. Shimizugumi asked Eiichi to become the company’s advisor, and he continued to provide management input over the next 30 years. Furthermore, the main building of the Fukagawa house is the only remaining structure built by Kisuke, the second-generation Shimizugumi head. The house, where Eiichi lived as he supported the company through its travails, is a fitting legacy and a testament to the skills of Kisuke and the ideal venue for studying Shimizu Corporation’s roots and spirit of innovation.

All this explains why the Former Shibusawa Residence is the centerpiece of the Novare complex, Shimizu Corporation’s “bridge to the future” (indeed, young Shimizu employees were visiting when I went there). Together with the Novare Archives, the site will open to the public at a future date. In the meantime, visitors to the area can glimpse the house from Shiomi Shibusawa Park along the canal. This is where the past, in the form of a building erected in the 1870s, and the future—symbolized by Shimizu’s achievement of Azabudai Hills Mori JP Tower, Japan’s tallest building, farther to the south in central Tokyo—meet.

The Former Shibusawa Residence, viewed from Shiomi Shibusawa Park. (© Nippon.com)

The entrance hall to Novare Hub, open to the public, is an exhibit space featuring displays related to Shimizu Corporation. (© Nippon.com)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The Former Shibusawa Residence, back in Kōtō after an absence of 115 years. © Hashino Yukinori of Nippon.com.)