Seki: Gifu’s Traditional Center of Swordsmiths

Guideto Japan

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Swordsmith Tradition

Seki in Gifu Prefecture is known for its cutlery. Located about 40 kilometers north of Nagoya in central Japan, this city of just 80,000 ranks alongside Solingen, Germany, and Sheffield, England, as one of the world’s three major cutlery producing areas. It is home to around 300 businesses involved in the cutlery trade and accounts for about half of all Japanese cutlery exports.

Seki’s history as a maker of fine blades began about 800 years ago during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), when a swordsmith from the province of Yamato (present-day Nara Prefecture) moved to Seki, then part of Mino Province, and established a workshop. Several years after the move, during the Nanbokuchō period (1336–92), the smith was influential in establishing Mino-den, which is counted among the five famous schools of Japanese swords making. Mino-den swords were reputed to “not break, not bend, and cut well,” making them items heartily sought after by samurai.

Kasuga Shrine in Seki. Founded as a subbranch of the main shrine in Yamato Province in 1288, it enshrines the guardian deity of blacksmiths.

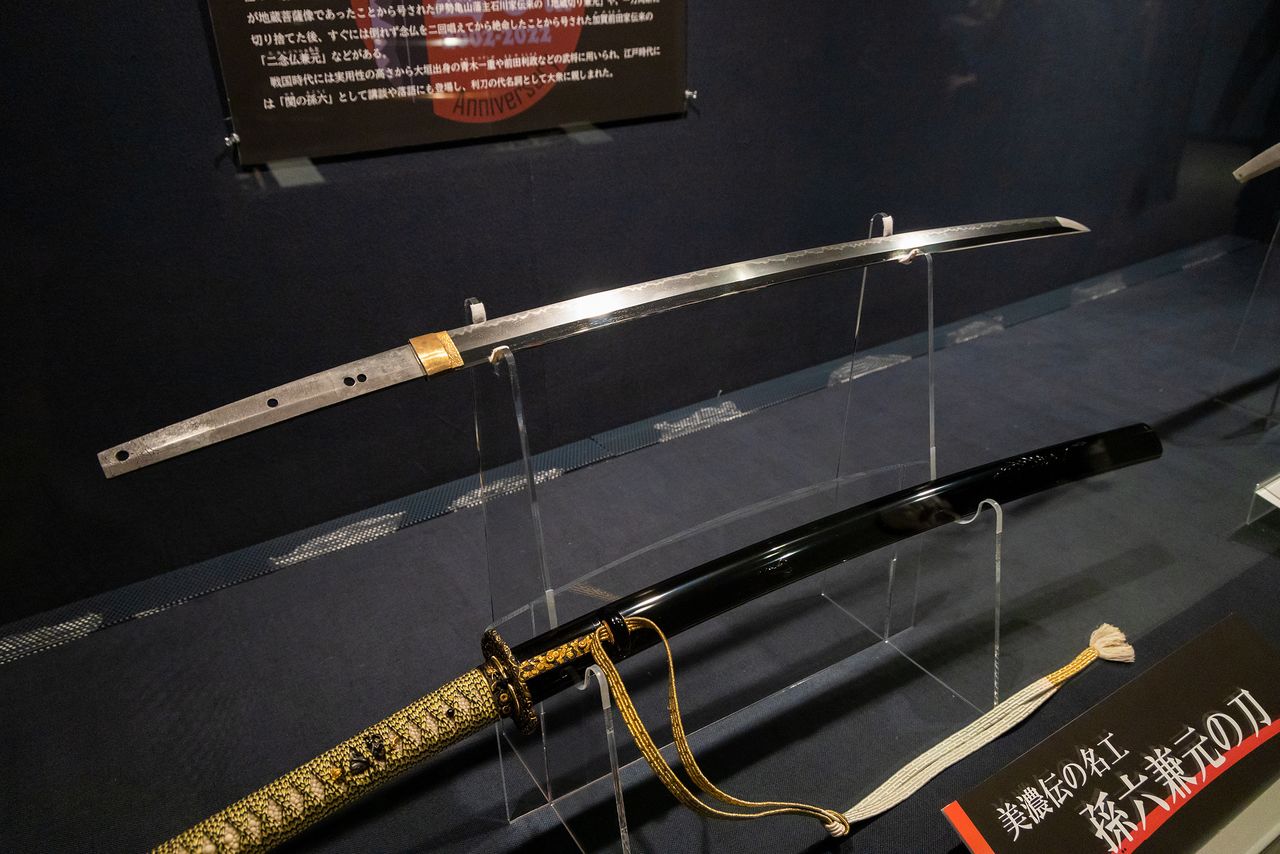

Izuminokami Kanesada is considered the most excellent swordsmith in Mino’s history. Starting with the blade Kasen Kanesada, which was owned by the first lord of the powerful Kokura domain Hosokawa Tadaoki, the swords he crafted were cherished by well-known warlord of the Warring States period (1467–1568).

Another master craftsman of the period was Magoroku Kanemoto. It is said that Mino daimyō Saitō Dōsan gave a sword forged by Magoroku as a present when he married his daughter to renowned warrior Oda Nobunaga; and writer Mishima Yukio owned one of the swordsmith’s military blades, which he used when he committed suicide in 1970.

A great way to delve into Seki’s rich history is with a visit to the Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum. In addition to exhibits of historical materials, sword fittings, and knives that convey the skills of Seki swordsmiths, there are also live demonstrations of traditional Japanese sword forging techniques and the works of craftsmen specializing in decorative external elements.

Exhibits at the Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum.

A sword forged by Izuminokami Kanesada.

Nurtured by Nature

Seki is blessed with all the essentials for smithing: water, wood, and earth. The Nagara and Tsubo Rivers flow abundant and clear, providing high-quality water for cooling red-hot steel. The region’s thick forests of pine offer fuel for the furnaces. The red clay of Seki is also ideal for making yakibatsuchi, a mixture of water, clay, ash, and other ingredients essential in treating steel.

A swordsmith demonstrates his technique at the Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum. Mino-den swords are made with steel melted using pine charcoal.

One of the most important steps in Japanese sword making is the process of folding the steel, which greatly impacts the quality of the blade. The metal is first heated to 1300 degrees Celsius and then beaten and folded in half. It is then reheated and beaten and folded again, with the process being repeated multiple times. The technique removes impurities and strengthens the steel with each additional layer of metal.

Although this hardens the blade, it also makes the steel more brittle. To counter this undesirable outcome, Magoroku devised a manufacturing method called shihō-zume that utilizes different types of steel of varying hardness in a sword’s assembly, resulting in strong and flexible blades characteristic of Mino-den.

The yokoza (at right) is the key figure in forging. Wielding a small mallet, he sets the pace for the other two workers, who swing larger hammers.

Once a sword is forged, yakibatsuchi is applied to the entire surface before quenching, with only a thin layer put on the blade side. The sword is first reheated in the forge before being immersed in water. The thin layer of yakibatsuchi allows the blade side to cool quickly, hardening it, while the back cools more slowly, increasing its flexibility and enhancing the sword’s sharpness and toughness.

The pattern on the blade, which appears on the part where soil is applied thinly, is where the swordsmith expresses his or her individuality. Seki’s red clay has few impurities and Magoroku’s symbol, the sanbonsugi pattern, is clearly depicted on the master’s blades.

A sword made by Magoroku Kanemoto. It is characterized by the sanbonsugi pattern resembling the silhouette of a row of cedar trees.

World-Renowned Cutlery

Along with sword making, Seki is known for blacksmiths called nokaji. These “field smiths” traditionally produced necessities such as kitchen knives, razors, and farming tools used in everyday life, and are also said to have forged custom-made cutlery to meet individual requests.

Demand for Japanese swords decreased as peace returned to Japan with the start of the Edo period (1603–1868), and many of Seki’s swordsmiths became nokaji to make a living. The art of sword making came under further pressure during the Meiji era (1868–1912) when the government banned swords, forcing many swordsmiths to turn to exporting military swords and ornamental goods to survive.

Despite these developments, the techniques cultivated over generations were handed down, and today they are still used to create cutlery revered by consumers around the world. Kai, a cutlery manufacturer that upholds the nokaji spirit, is a shining example of this.

The headquarters of Kai Industries.

Kai got its start in 1908 as a manufacturer of pocketknives. In 1932, the company found success when it started selling Japan’s first razor with a replaceable blade. In 1951, its disposable long-blade, lightweight razor became a hit, spreading Kai’s fame nationwide.

The company currently boasts the top domestic market share of disposable razors, nail clippers, and household knives. It also manufactures medical products as well as barber scissors, chef knives, and other professional cutlery. An international company, it sells its products in 100 countries around the globe, with the overseas market accounting for nearly half of its revenue.

A display of Kai’s early long-blade, lightweight razors.

Kai has a diverse lineup of products, including all the nail-cutters here.

Kai over the last 40 years has followed in the footsteps of the great swordsmith Magoroku Kanemoto in developing its Seki Magoroku brand of cutlery, which boasts more than 1,200 items that combine functionality and beauty.

In particular, its lineup of household knives in the series are known for their sharpness, reminiscent of Japanese swords, and for being reasonably priced and durable. They are products that truly embody the nokaji spirit.

A display of items from Kai’s two major kitchen knife brands, Seki Magoroku and Shun.

Traditional Craftsmanship in Modern Kitchen Knives

Kai’s Yamato Tsurugi factory in Gujō is located just upstream of Seki on the Nagara River. It is where the company manufactures its Seki Magoroku Kaname brand of kitchen knife, which it released in November 2022.

The knife’s blade is gently curved, bringing to mind a torii, a style common in Japanese swords during the Kamakura period that is said to allow force to be applied efficiently. The slanted shape of the peak has its roots in traditional Japanese knives, making it easy to perform fine work such as slicing meat. In addition, Kai has pursued functionality down to the smallest detail with features such as an octagonal pattern that makes the knife easy to grip.

Ōtsuka Jun of Kai’s design department describes the knife as “beautiful, but with a practical design that makes it easy to use.” Bearing the sanbonsugi pattern on its cutting edge, the knife pays homage to the legacy of Magoroku Kanemoto.

The Seki Magoroku Kaname is the pinnacle of the brand.

The manufacturing process is divided into around 30 steps at the factory, including surface grinding, mirror polishing, and blade edging. The thickness of the cutting edge is measured in 0.1 millimeter units, a process that is done by hand.

The knife’s sharpness ensures a clean cut, preserving the flavor and integrity of ingredients. This is particularly valued in washoku (traditional Japanese cuisine), which has grown in popularity globally. Kai is helping support the cooking tradition with its Kaname and other knives born from the legacy of Seki sword making.

Wet type blade edging is one of the most important steps in the manufacturing process and is only done by a craftsman with many years of experience.

The blade ensures a clean, beautiful cut each time.

Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum

- Address: 9-1 Minamikasuga, Seki, Gifu Prefecture

- Hours: 9:00–16:30

- Closed: Tuesdays, days after national holidays (excluding weekends), and New Year holidays

- Admission: Adults ¥300, high school students ¥200, junior high and elementary school students ¥100

- Access: About 5 minutes on foot from Sekiterasu-mae Station on the Nagaragawa Railway

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com. Banner photo: Demonstration of Japanese sword forging at the Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum.)