A Basic Guide to Japanese Etiquette

Funeral Etiquette in Japan

Guideto Japan

Lifestyle Culture Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Buddhist Funerals the Norm

Most modern-day Japanese pay scant attention to religion in daily life, but things are different when it comes to funerals. These are officiated according to Buddhist rites nearly 90% of the time, and while the sutras chanted may differ depending on the region or the school of Buddhism, the rites generally follow the same pattern. After the chanting of sutras and offering of incense by mourners, the deceased is cremated, the soul enters the next life, and the remains are interred. Shintō, Christian, or non-religious rites are also performed, but altogether such funerals account for only around 10% of the whole.

Up until the early years of the Edo period (1603–1868), funerals were held privately at the deceased’s home, with family and community members in attendance. But once the system which obliged families to affiliate themselves with a Buddhist temple went into effect during the seventeenth century, temples began conducting funeral rites. Individuals were registered with a family temple at birth, obliged to support their temple as danka parishioners, and entered the Buddhist afterlife after receiving a kaimyō posthumous name.

The officiating priest bestows a kaimyō expressing the deceased’s personality or achievements. This kaimyō is used on the ihai memorial tablet (center) and the gravestone. (© Pixta)

Although Buddhism waned in influence after the Meiji era (1868–1912), the custom of Buddhist funeral rites remained, so much so that people nowadays often think of Buddhism only in relation to funerals.

It is important to be aware of the distinctive funeral customs and manners practiced in Japan and the basic flow of the rites in order to be prepared when a death occurs.

Funeral Rites

Funeral ceremonies generally consist of a wake, funeral, and farewell ceremony, followed by cremation, over a period of three days so that the body does not decay unduly, as embalming is not usually employed. Today, though, crematoriums are often backlogged and it may be some days before the funeral ceremony can be held.

The wake on the day preceding cremation traditionally took place to keep evil spirits from entering the body. Mourners would keep vigil throughout the night, burning incense and spending final hours with a loved one. Until the late twentieth century, funerals were held at home. Nowadays, they take place at funeral halls, and it is common to hold an abbreviated wake. Following the wake, family members gather to pray for the soul of the deceased, friends and acquaintances attend the farewell ceremony, and finally the casket departs for the crematorium in the presence of the family.

Persons notified of a death usually attend either the wake or the farewell ceremony. If they had been especially close to the deceased, they might attend both, or visit the family at home before the wake to offer their condolences.

The family accompanies the body to the crematorium after the farewell ceremony. (© Pixta)

If you cannot attend the funeral, it is customary to send a condolence telegram or convey a message of sympathy. Having done so, you should also visit the family before the forty-ninth day of post-funeral observances has elapsed.

Proper Attire

In the past, wearing the all-black mofuku funeral outfit to a wake was viewed as unseemly, taken as a sign that the death had been anticipated. In practice, though, many people attend the wake in mofuku. Men attending a wake after work can wear a black necktie with their suit, or a dark suit with a white dress shirt. Clothing should be in a subdued shade; accessories in animal prints or fur are inappropriate.

Formality of dress depends on the individual’s relationship with the deceased. Family members wear full formal dress, while attendees wear black formal wear. Younger women can wear a dark suit or pantsuit, and younger men a dark suit. Today, in fact, even the chief mourner often wears semi-formal attire.

Neckties and stockings should be black. (© Pixta)

The Kōdenbukuro Money Envelope

Persons attending a funeral should take a kōden money offering. This was originally to pay for incense, but nowadays the offering is welcome as a contribution toward defraying funeral expenses.

Present the kōden to the receptionists when signing the condolence book. (© Pixta)

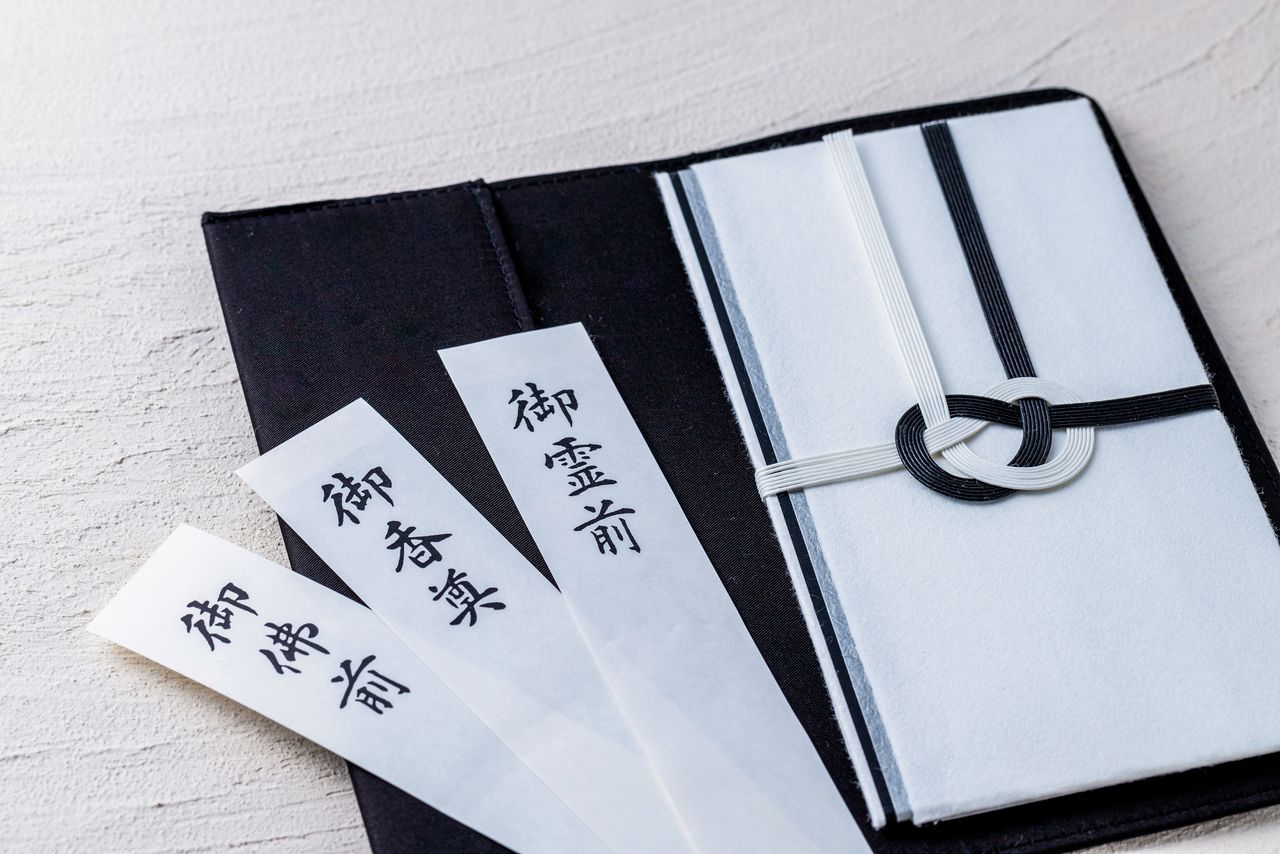

Special envelopes for kōden, called kōdenbukuro, are sold at stationers and convenience stores. The envelopes carry different kanji on the front, which vary depending on religious affiliation, but 御霊前 (goreizen; offering to the spirit of the deceased) is acceptable in all cases.

Persons other than family usually offer ¥5,000 for kōden. Bills used for kōden should not be new, implying that the death was expected and that the money had been prepared in advance. If fresh bills are used, they should be folded once to “break them in.” It is also customary to insert the bills with the reverse side facing frontward, although recipients will generally overlook this minor breach of etiquette.

Write your name on the lower part of the envelope in light black ink, using a fudepen pre-inked brush-pen. (© Pixta)

People usually carry juzu prayer beads at funerals; the beads’ design or the way they are carried differ depending on the school of Buddhism adhered to. However, they are not essential, so there is no need to rush out to buy them.

On arriving at the funeral hall, express your condolences, briefly but sincerely, so as not to take up the family’s time.

The chief mourner wears a rosette for identification. (© Pixta)

The Farewell Ceremony

The officiant chants sutras at the wake and the farewell ceremony, and mourners offer incense to the deceased. Offering incense is a way for mourners to purify themselves as they offer a prayer for the deceased.

The altar for incense-burning is placed in front of the casket and the memorial photograph. (© Pixta)

Offering incense by holding it up between the brows is a gesture of respect. This gesture is performed either once or a few times, depending on the Buddhist school. If in doubt, look for guidance at how the priest or the chief mourner, who is the first to offer incense, do it.

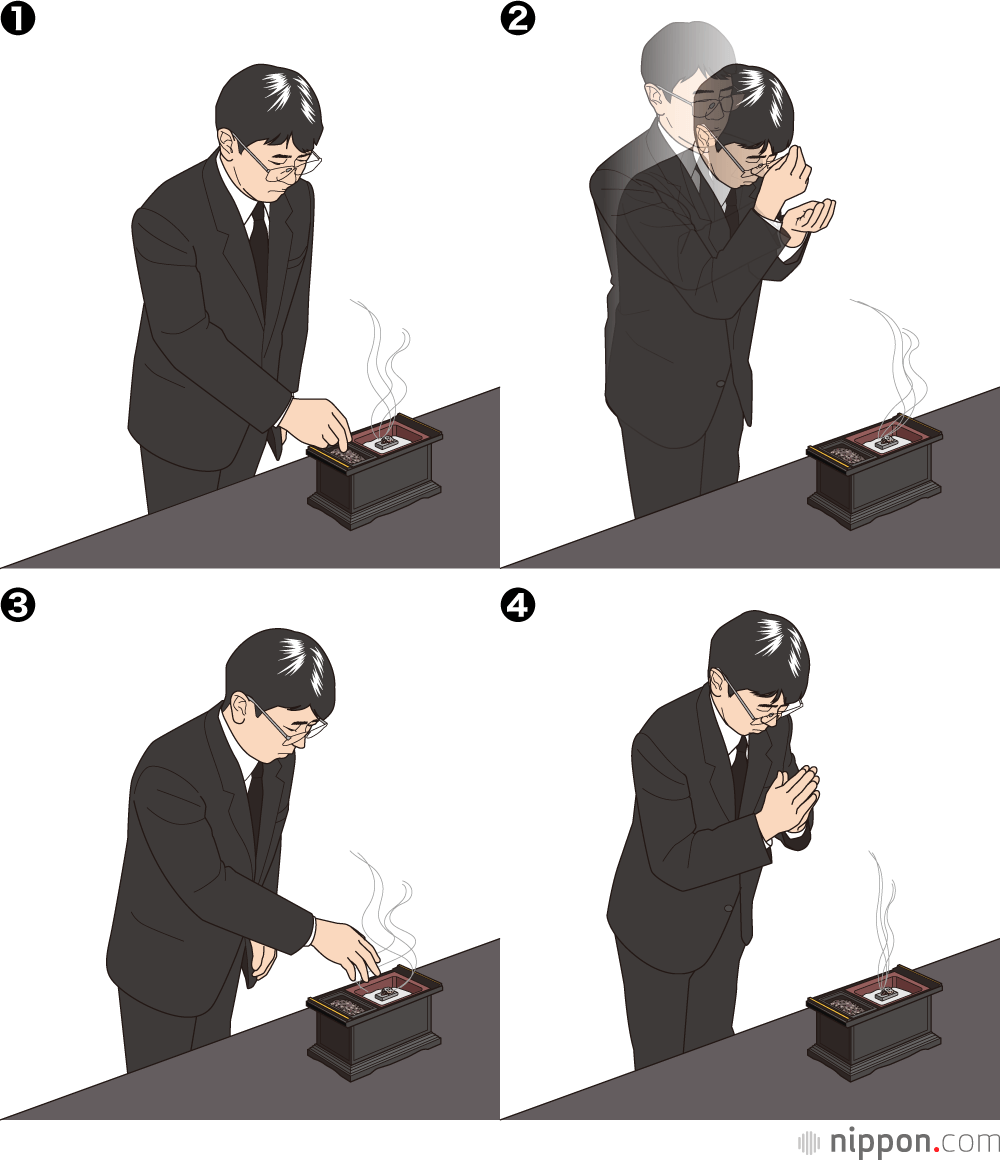

One example of how to offer incense:

- When your turn comes to approach the altar, bow to the family and the priest and approach the incense burner. Bow to the memorial photograph.

- Take a pinch of incense between the thumb and forefinger of your right hand. (1)

- Bring your left hand up, palm cupped upward, to eye height while also bringing the right hand up. Without moving your hands, bow slightly and bring the incense close to your brow. (2)

- Drop the incense onto the incense burner (3) and join your hands in prayer (4).

- Take a step backward, turn and bow to the family once more, and return to your seat.

If, for religious reasons, you prefer not to take part in this ritual, let the chief mourner know beforehand via the receptionist. You will no doubt be told that the point is to pay respects to the deceased and to perform whatever rite is acceptable to you.

Following incense offering and the farewell ceremony, the family may host a meal for mourners. This is a final repast for sharing memories of the deceased, and you are expected to participate, even if only for a brief time. Avoid topics that have nothing to do with the deceased and do not drink alcohol to excess.

The custom is to offer a light meal after the wake, but is it increasingly common nowadays to also invite mourners to a meal after the farewell ceremony. (© Pixta)

After the Funeral

After the funeral, you will be handed a small packet of salt to sprinkle over yourself in the entrance to your home to avoid bringing impurity inside. You may also receive a small gift to thank you for attending.

The gift is usually confectionery, nori, or some other consumable, selected “so that sadness does not linger.” (© Pixta)

Some time after the funeral, you may receive a kōdengaeshi return gift. No thanks are expected; you may simply offer words such as “Please take care of yourself” in return. You can also decline a kōdengaeshi when you present kōden, keeping in mind the heavy expenses the family must bear for the funeral.

Sometimes you learn of a death later, usually in early December, when a postcard arrives with the message that the family will not be sending out New Year greetings because of a death in the family. New Year greeting cards are not customarily sent to a family in mourning, but if you like, you may send a greeting in mid-January or so.

These days, relatives are often scattered far and wide, and given the effort and expense, there is a marked trend toward less elaborate funerals. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more common to hold a small funeral, with only close family in attendance. As long as the family can mourn their loved one properly, the format of the ceremony makes little difference.

(Originally published in Japanese. Supervised by Shibazaki Naoto, associate professor at Gifu University, who specializes in manners education from a psychological perspective, works to guide etiquette educators, and is an instructor in Ogasawara-ryū etiquette. Illustration by Satō Tadashi. Banner photo © Pixta.)