A Basic Guide to Japanese Etiquette

“Shūgi” and “Kōden”: Money Gifts Expressing Congratulations or Condolences

Guideto Japan

Lifestyle Culture Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Avoiding Symbolic Impurity

Money gifts are part of Japan’s culture. Shūgi (congratulatory monetary gifts) are often given for milestones such as school entrance or graduation, the Shichi-Go-San ceremony for children, coming of age, starting a job, marriage, or the birth of a child.

In the past, however, gifting money was believed to leave a taint, so there was no such custom on happy occasions. Traditionally, gifts in kind were the norm for congratulatory gift-giving; monetary gifts only became widespread in modern times as the currency-based economy developed. Many people use brand-new bills for shūgi because of the idea that new bills are free of impurity.

A colorful assortment of shūgi bukuro envelopes. In general, the larger the amount of the gift, the fancier the envelope used. (© Pixta)

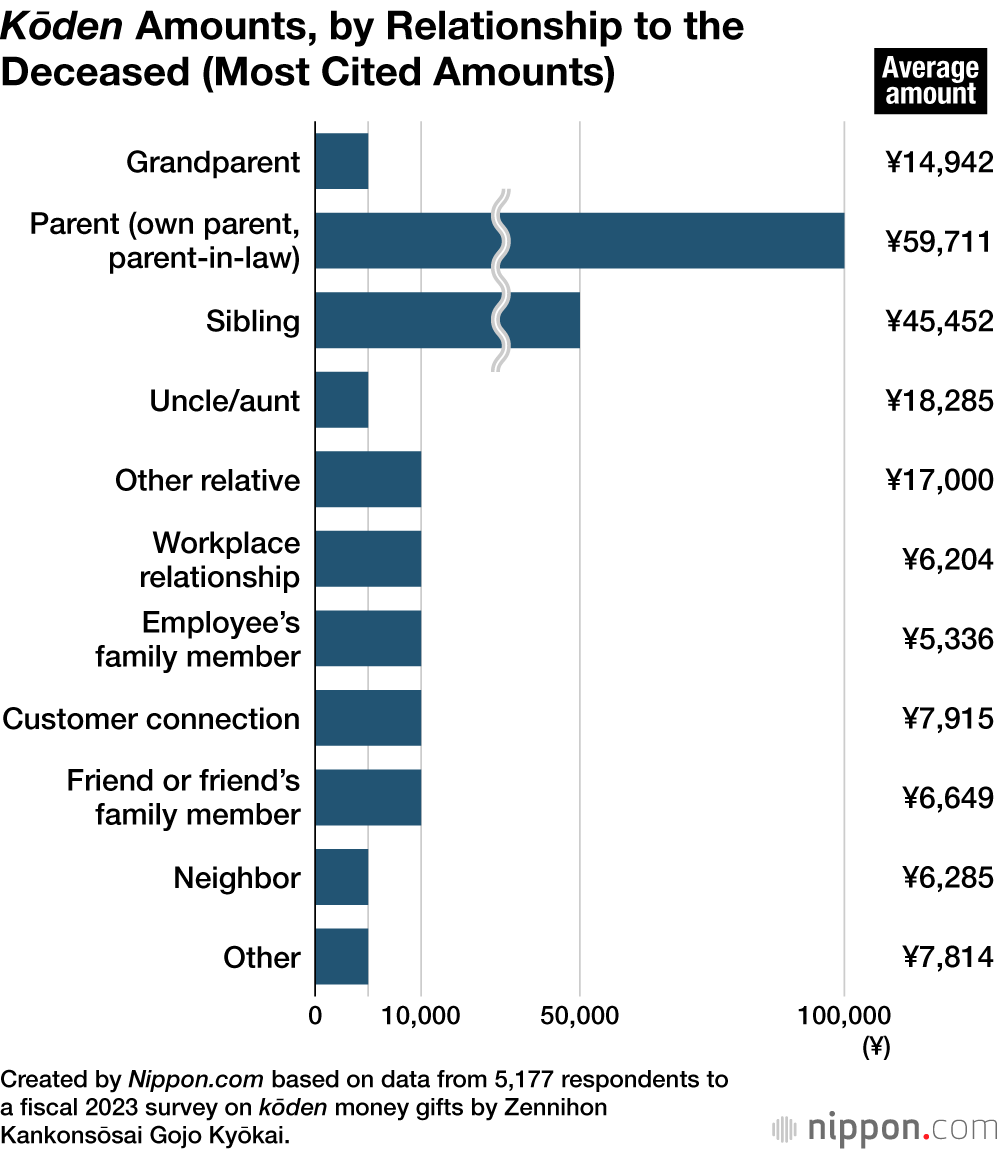

Instead, gifts of money known as kōden were associated with infelicitous occasions such as funerals. Although the custom of giving money at a funeral was prevalent among the upper classes beginning in the Muromachi period (1333–1568), it was more common for food or similar offerings to be given to the grieving family. This eventually morphed into kōden as a recompense to the family for spending money on incense and flowers.

Money, which is viewed as soiled or impure, is never handed over directly; money gifts are placed in special envelopes for that purpose. Stationers stock a wide variety of shūgi and kōden envelopes, whose designs vary depending on what they are for and the amount of the gift. Kōden or other money gifts in a token amount may be placed in a basic envelope. The amount for shūgi, however, tends to be high, and the envelope is inside a folded washi outer cover called orikata. This practice derives from the etiquette of samurai families of wrapping gifts beautifully in washi.

Superstitions Related to Gift Amounts and Wrapping Styles

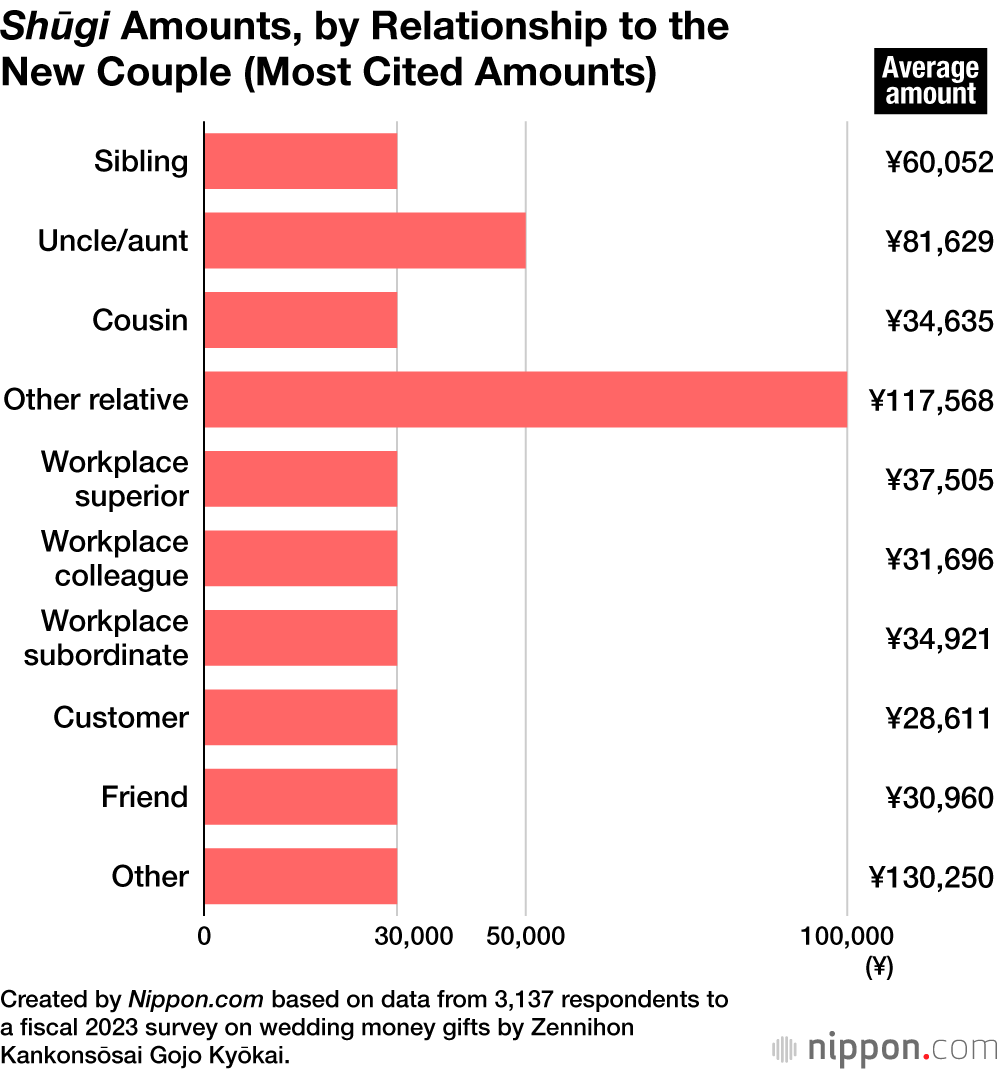

Cash gift amounts generally range from ¥5,000 to ¥30,000, depending on the donor’s relationship with the recipient, and the first number of the sum is often an odd number. This convention originates in ancient Chinese thought concerning lucky numbers. Even numbers, which are divisible, are especially frowned upon in the case of wedding gifts, to avoid any intimation of “splitting apart.” If the donor wishes to give ¥20,000, the bad luck associated with even numbers can be circumvented by using one ¥10,000 bill and two ¥5,000 bills, creating the desired odd number. Similarly, numbers 4 (shi) and 9 (ku), homonyms for “death” and “suffering,” respectively, are to be avoided, as they will discomfort the recipient.

Bills used for kōden should not be new, as this carries the implication of having expected the death and prepared in advance; some people make a point of making a fold in fresh bills to “break them in.” It is also customary to insert the bills with the reverse side facing frontward. (© Pixta)

Donors write their name and address on the back of the envelope and the amount of the gift on the front. The amount is often written using traditional kanji instead of numerals, which looks impressive and is also intended to prevent altering the figure. However, using Arabic numerals is also common.

Double-wrapped envelopes for money gifts sold in stores come properly folded, but it pays to remember the basics. Depending on whether the gift is shūgi or kōden, the back fold of the outer wrapping is handled differently. For shūgi, the bottom part of the fold overlaps the top part, which has the meaning of “holding happiness in.” Conversely, for kōden, the top part of the fold overlaps the bottom part, “so that sadness does not remain.”

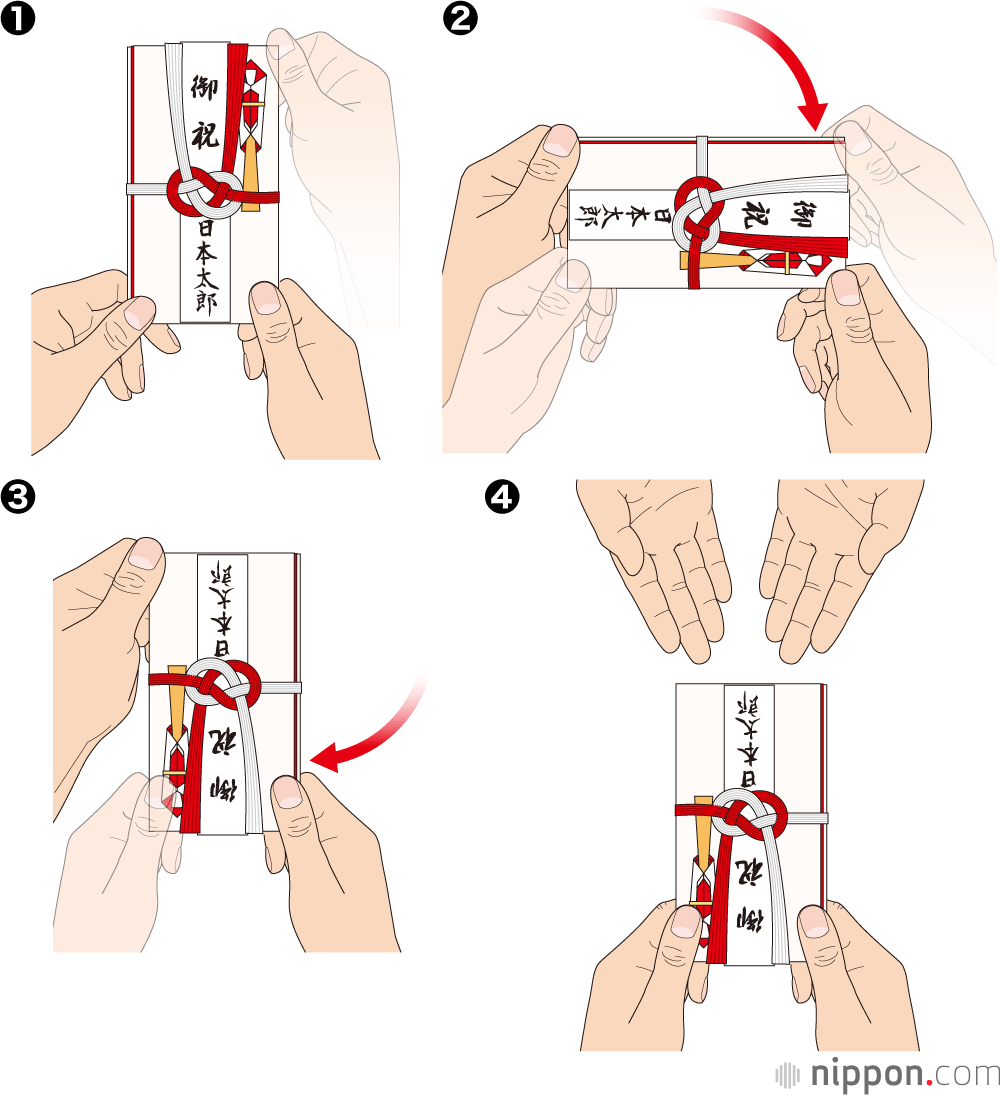

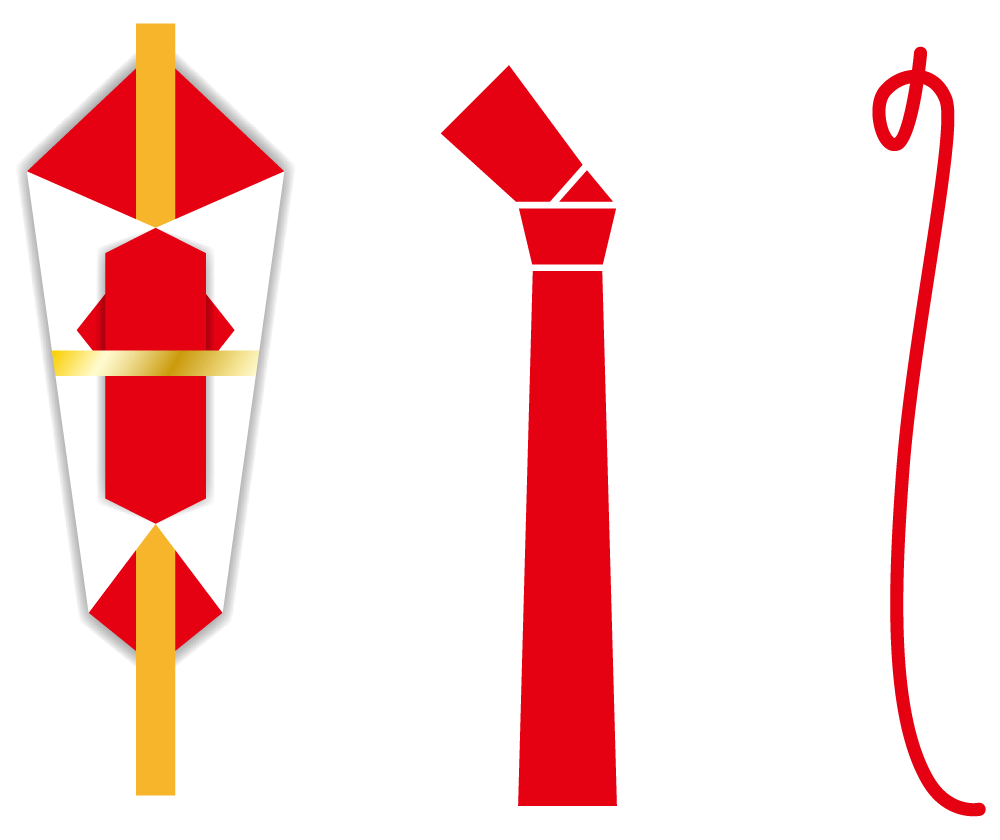

Orikata cover folding sequence and mizuhiki positioning. (© Nippon.com)

The Various Meanings of Money Envelopes

Folded orikata covers for money gifts are held closed by mizuhiki, decorative strands of knotted washi paper twists. Some claim that mizuhiki are adapted from the fastenings that Heian period (794–1185) nobles used to close missives containing poems. Mizuhiki also have the meaning of washing away impurities with water (mizu).

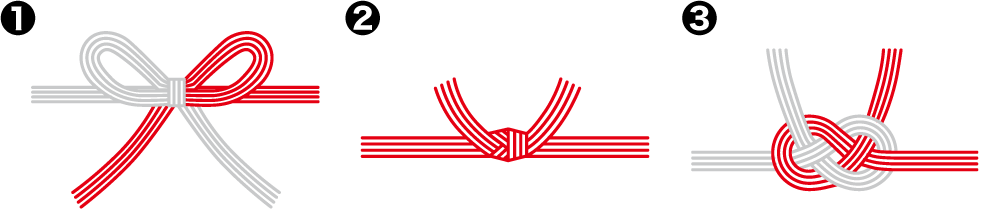

The two main types of mizuhiki knots are morowana musubi (as in example 1 below) and musubikiri (examples 2 and 3). The first comes apart easily, like a ribbon, and is for happy occasions, such as a birth or school entrance, when hopes are that the occasion will be repeated. The next two are tight, fixed knots: they are suitable for occasions such as funerals, illness or injury, or weddings, which hopefully will be one-time events.

Mizuhiki knots

- Morowana musubi: For celebratory occasions whose repeat is welcomed. Also called morobana musubi, hanamusubi or chōmusubi.

- Musubikiri, mamusubi: For occasions, such as a wedding or a funeral, for which no repeat is desired.

- Musubikiri, awabimusubi: Same as above. Also called awajimusubi.

Standard colors for money envelopes are red and white for celebratory occasions and black and white for funerals. When a money gift is offered to someone sick or injured, a red and white envelope is used, to anticipate recovery, and a musubikiri knot is used, to express hope that the situation will not recur.

Shūgi bukuro envelopes include noshi in the upper right-hand corner. Originally, noshi was a thin strip of dried abalone which, when eaten to accompany sake, had the felicitous property of calling down the kami spirits to ensure the partaker’s prolonged vitality. Dried abalone was also an offering of the highest caliber to the kami. Noshi are now typically symbolic paper items. They appear on seibo and chūgen seasonal gifts as well, but since abalone comes from the sea, noshi is omitted for gifts of marine products. However, there is no noshi on kōden bukuro for funerals.

Examples of noshi. From left, a folded paper containing a long strip representing dried abalone; a simplified representation of noshi; a stylized rendering of noshi (のし) in hiragana. (© Pixta)

Traditionally, the last step is to write the purpose of the gift on the envelope with a calligraphy brush. For a wedding or other happy occasion, 寿 (kotobuki; best wishes) or 御祝 (oiwai; congratulations) are good options. For kōden, the kanji used may depend on religious affiliation, but 御霊前(goreizen; offering to the spirit of the deceased) is universally accepted. In the case of kōden, the writing is done in light black ink, symbolizing that tears of sorrow have diluted the writing. Fudepen pre-inked brush-pens for this purpose are widely available in stores. In all cases, the name of the donor should be written at the bottom on the front cover or envelope.

Many envelopes sold in stores come with the purpose of the gift already printed on the envelope. (© Pixta)

Wrapping any sort of money envelope in a fukusa silk wrapping cloth will prevent soiling and is a sign of good manners. Fukusa are like miniature furoshiki, although rectangular envelope-type versions are also popular now. For happy occasions, the fukusa may be a warm, bright color. A more subdued hue is best for funerals, although purple will do for all occasions.

When presenting a money envelope, it should be passed over using both hands, accompanied by a sincere expression of congratulations or condolences.

An envelope-style fukusa silk wrapping cloth. (© Pixta)

How to Present Shūgi or Kōden

- Hold the envelope with the front facing you, holding the bottom corners with both hands. Then move your right hand to hold the top of the envelope.

- Rotate the envelope clockwise 90 degrees. Move your left hand to what is now the bottom left of the envelope and your right hand to the top right.

- Rotate the envelope a further 90 degrees so that the front faces the recipient, and move your left hand again to what is now the envelope’s bottom left.

- Using both hands, present the envelope to the recipient.

Today, it is common to give a return gift, called uchi-iwai, for congratulatory gifts received; the value of the return gift is set at a certain percentage of the amount received. Originally, this return gift was a message announcing a happy occasion to relatives. No return gifts are given for kōden, as this would imply a “repeat” of the occasion. But the culture of offering money at a wedding or funeral is rooted in the spirit of mutual aid, and givers or their families are likely to eventually receive shūgi or kōden when the time comes.

Otoshidama New Year Gifts

Another kind of money gift is the otoshidama, a small sum of money in a pochi bukuro envelope given at New Year to children by parents and other relatives. This derives originally from the custom of eating seasonal kagami mochi rice cakes for good health. While that practice continues, other items were later gifted, and the otoshidama became a present of money in the postwar era.

Kagami mochi at left, and a pochi bukuro envelope at right, which is used to present otoshidama money. Pochi meaning “a little,” signifies it is just a small amount. (© Pixta)

(Originally published in Japanese. Supervised by Shibazaki Naoto, associate professor at Gifu University, who specializes in manners education from a psychological perspective, works to guide etiquette educators, and is an instructor in Ogasawara-ryū etiquette. Illustration by Satō Tadashi. Banner photo © Pixta.)