Letting It All Hang Out: Japan’s Three Great “Naked Festivals”

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Encountering the Gods in the Nude

The hadaka-matsuri, or “naked festivals,” are among the most eccentric of Japan’s happenings, featuring mainly male participants who cover themselves with nothing but a loincloth known as a fundoshi, if that. Hadaka-matsuri are intended to cleanse the impurities that have accumulated over the previous year and express hopes for peace in the coming year, and as a result they are generally held during the coldest part of the year: at year’s end and at New Year. Participants bathe in purifying cold water, emerging with steam rising off their bodies. To onlookers, this steam represents the passion and intensity of the festival itself.

The tradition of participating in the near-nude stems from the ancient custom of petitioning the Shintō gods or Buddhist deities in a state that mimics a newborn baby who is free of impurities. Prior to a ceremony, hadaka-matsuri participants abstain from eating meat and purify their bodies by pouring water over themselves outdoors. With their purified skin exposed, they then ritually shove and grapple with each other.

The hadaka-matsuri held as a conclusion to the New Year’s ceremony known as shūshō-e is even more intense. Shūshō-e, which is held to petition for the happiness and good fortune of the masses, culminates in the kechigan held on the final day and features an intense melee.

The Somin-sai at Kokusekiji in Iwate

(Third Saturday of February, Ōshū, Iwate Prefecture; the event took place in its standard form for the last time in February 2024. See below for details.)

Participants dousing themselves with purifying water. (© Haga Library)

An ancient tale tells of Somin-shōrai, who was rewarded for assisting the gods with eternal protection from disease and disaster. This became the focus of a folk belief held throughout Japan in which people write the words “The descendants of Somin-shōrai” on a piece of paper that they display at the front door of their homes as a prayer for peaceful, uneventful times. Over the years this developed into the hadaka-matsuri known as the Somin-sai. This festival has been carefully preserved throughout the Tōhoku region, and especially in Iwate Prefecture.

One of the oldest and largest such festivals was held through 2024 at a temple known as Kokusekiji, in the city of Ōshū, Iwate Prefecture. There festival participants vied to capture the somin-bukuro, a sack said to ward off evil, guard against disease and disaster, and ensure a good harvest. The sack contains hexagonal wooden dowels measuring about three centimeters in length, amulets with words inscribed on each side said to contain the power of Somin-shōrai. In the past, kechigan was held on New Year’s Day according to the lunar calendar; in modern times it has been held on the third Saturday of February each year (February 17 in 2024).

Youths mount a three-meter pile of prayer sticks and sing folk songs. (© Haga Library)

In the festival’s traditional form, participants disrobe in the freezing night air, purify themselves in river water, and then offer prayers at the Yakushidō and Myōkendō halls of the main temple. After repeating this process three times, the temple bell is rung, a bonfire of pine wood is lit in front of the temple hall, and the participants use the power of this fire to further purify themselves. During this entire process, the men shout “Jassō! Joyasa!” (“Out with evil!”) as they spiral deeper and deeper into a frenzy.

Children wearing oni (ogre) masks are carried to the festival site. (© Haga Library)

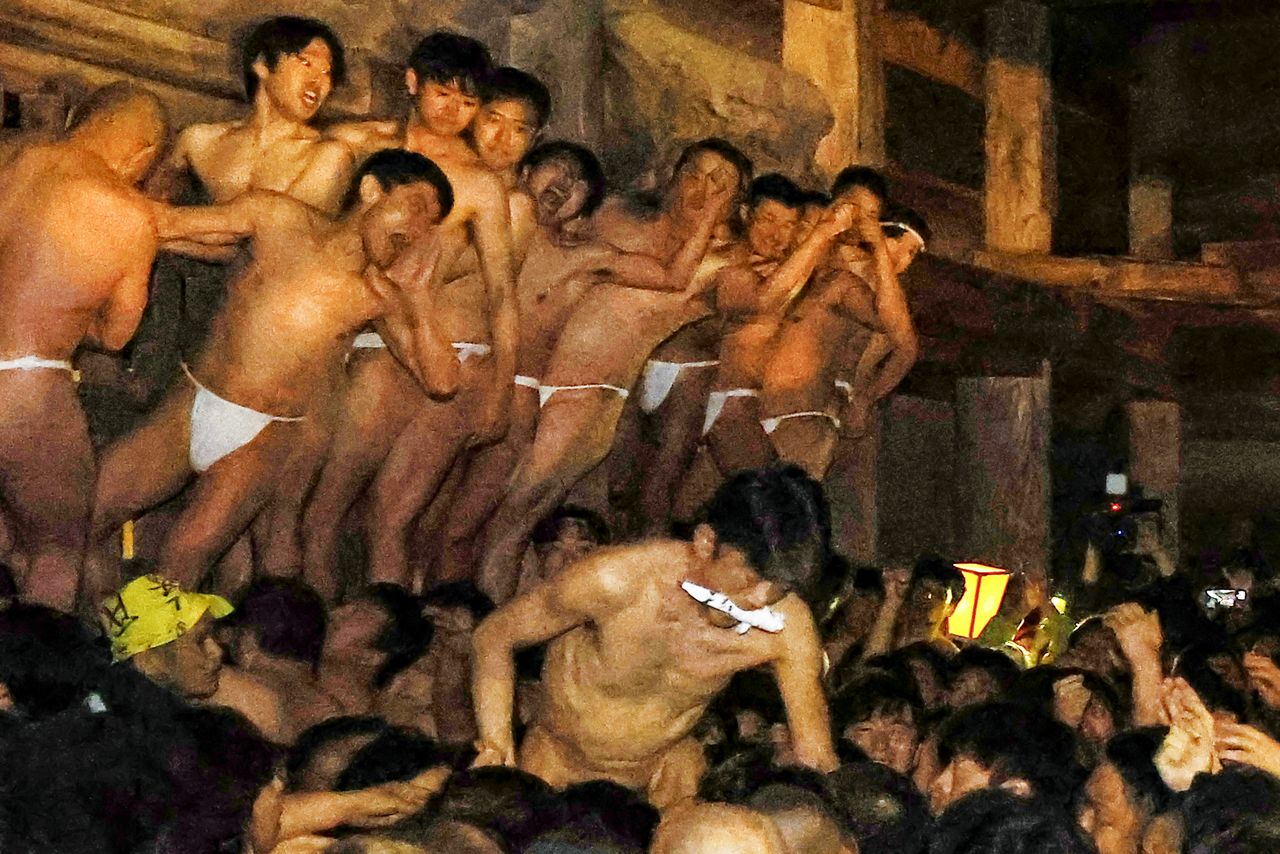

Once two seven-year-old boys (counted by the traditional Japanese system) have worshipped, the struggle within the main temple hall to capture the somin-bukuro begins. The thrashing of the naked men jammed into the main hall truly resembles something more like hand-to-hand combat than a religious ceremony as they scramble to capture the sack of amulets.

The Somin-sai was held for the last time in 2024. Starting in 2025, only the ritual burning of prayer sticks will be held. (© Haga Library)

The final “battle” takes place outside the snow-covered temple hall. The group, whose numbers have by now dwindled to around 100, advance—all the while pushing and shoving each other—to the final site located about two kilometers away. After descending a snowy slope, the so-called tori-nushi, or the last person left holding the amulet bag, is determined. And with this, the festival ends, and the men put on their clothing back on and return to their normal daily lives.

For over a thousand years, the participants in the Somin-sai at Kokusekiji participated in the festival completely nude. However, in an acknowledgment that times have changed, in 2007 it was decided that they would wear loincloths. Then it was announced that the 2024 festival would be the last, as the parishioners of the temple fell to only nine households, meaning that there were not enough people to make the amulets and carry out all the other tasks required to hold the festival. Many lamented the end of this tradition, as many others expressed hope that it would restart someday in the future.

February 17, 2024, saw the final battle to determine who captures the good luck amulets. The tori-nushi was moved to tears by the overflowing crowds. (© Haga Library)

Okayama’s Saidaiji Eyō

(February 17, Okayama, Okayama Prefecture)

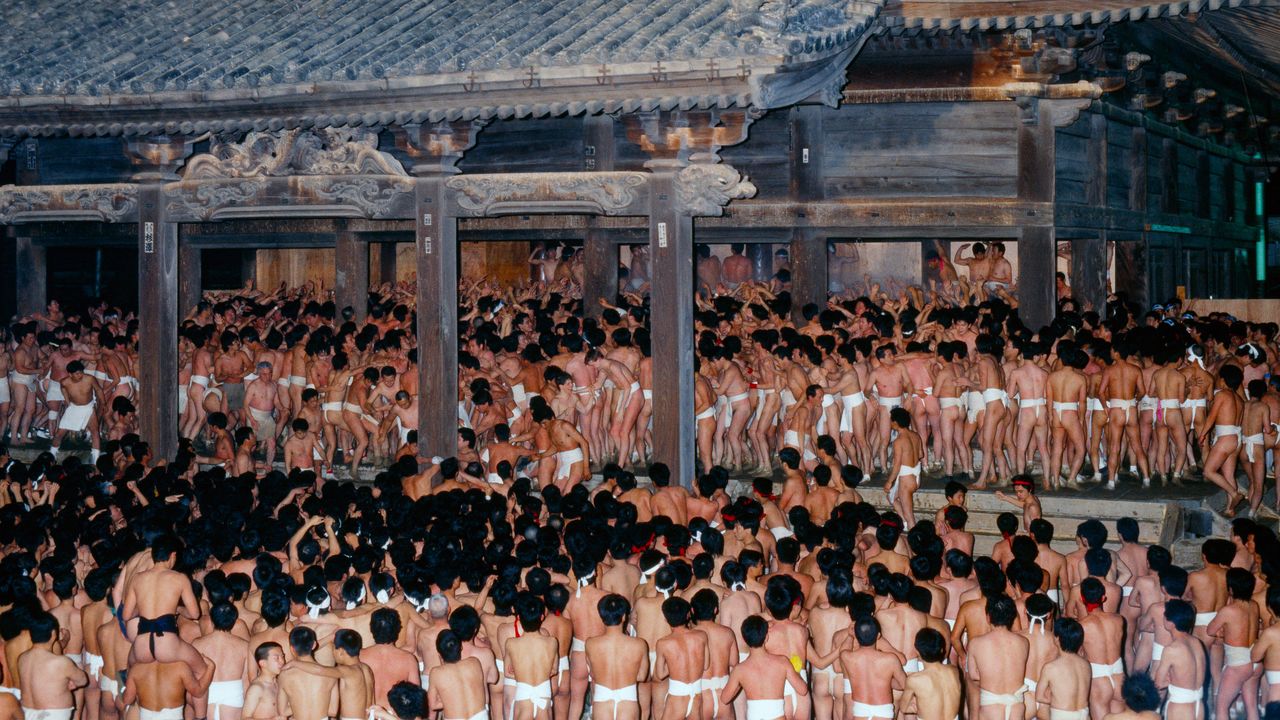

Throngs of participants in their loincloths. (© Haga Library)

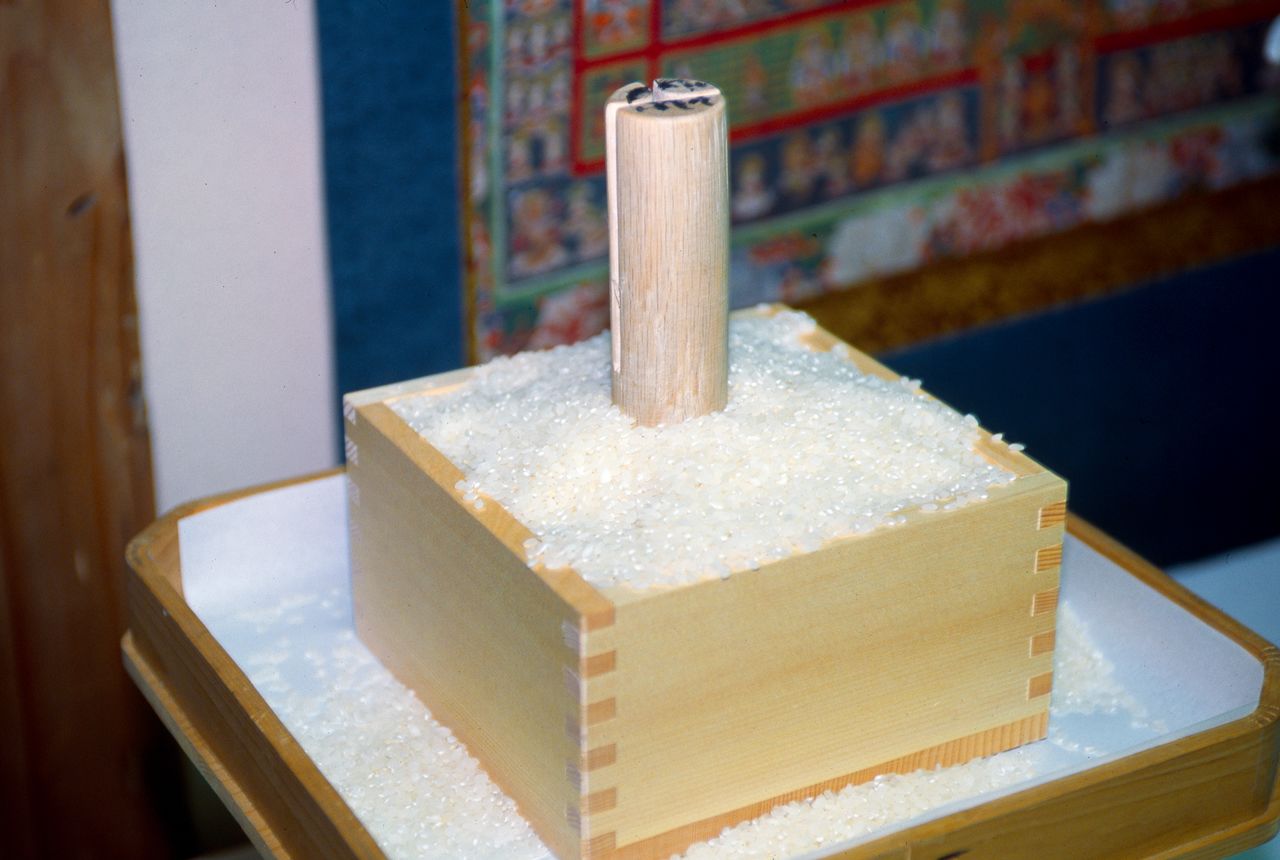

A ceremony known as eyō (also part of the Shūshō-e kechigan tradition), in which approximately 10,000 nearly nude men battle for a shingi (wooden amulet), is held at the Okayama Prefecture temple Saidaiji over a 14-day period starting on New Year’s Day. The shingi amulet is made of a split dowel of aromatic wood about 20 centimeters in length, representing the forces of yin and yang and invested with good fortune through prayers that take place in the main temple hall during the New Year season. Anyone who possesses the amulet is said to gain one year’s worth of good fortune.

The origin of the festival can be traced back to 1510. Amulets known as goō are prayed over during the New Year’s festival season. Thought to bestow divine favor, they gradually became the object of the struggle that takes place during the festival. The amulets have since come to be enclosed in wood to make them less prone to damage during the struggle. The tradition of worshippers participating in the nude began as a way to allow them maximum mobility, which was thought to reduce the chance of injury, and to allow them to engage in ritual bathing.

Participants reaching out for good fortune.(© Haga Library)

On the day the eyō is held, such a large number of nude festival-goers gather in the temple hall that they can hardly move. At ten at night, the lights in the hall are turned off, approximately 100 amulets bundled in willow branches are thrown into the room from a window near the ceiling, and the battle to capture them begins. Next, two shingi amulets are thrown into the darkened room. When the lights are then turned on in the room, the crowd surges as no one knows for sure where the shingi are. All they can do to locate the amulets at this point is try to use scent of the aromatic wood enclosing them as a clue to where they are.

Those who are lucky enough to find and grasp one of the amulets run outside and announce their victory. A brief scuffle then takes place and the ceremony is concluded. The two participants who managed to capture an amulet, out of the thousands taking part, are deemed the ceremony’s “lucky men” and are lauded as heroes in the local community.

Anyone who purchases a loincloth and tabi socks at the temple may participate in the festival. The only requirements are that participants keep in mind the fact that as it is a religious festival, they should purify both mind and body.

The winners stick the shingi in a container filled with white rice. After the festival, local representatives offer prayers to the shingi. (© Haga Library)

The “Hayama-gomori” of Fukushima

(Held for three days starting on November 16 according to the lunar calendar, Fukushima, Fukushima Prefecture)

While most of the festival is not open to the public, there are no restrictions on viewing the ta-asobi portion. (© Haga Library)

Finally, let us turn to one of the lesser known festivals, but one that gives spectators a glimpse into the mystery of a more primitive form of religious practice. Kuronuma Shrine is located in the district of Kanezawa in the southern portion of the city of Fukushima, and it is the location of a secret ceremony that has taken place for over a thousand years in which omens from the gods are bestowed on humans. The place where the gods are said to descend, known as “Hayama,” is considered off-limits to visitors. The only time anyone is allowed there is during the festival, which is held only once a year.

For a three-day period, the men who will enter the area purify their bodies in a hall located near a the shrine. They strip completely naked at a sacred well at five in the morning each day and douse themselves with the freezing water as they offer their own as well as their friends’ and family members’ prayers. Their diet during this period consists solely of hakusai cabbage and daikon radish harvested locally, along with white rice steamed in well water.

Purification ceremony inside a hall. (© Haga Library)

In 2023 the event began on December 28; in 2024 it is scheduled for December 20–22. On the night of the first day the participants, wearing nothing but their loincloths, engage in a ritual ceremony that re-creates rice farming. Drums are beat in a representation of thunder and clouds and the participants move in procession in circles while praying for rain. They then collide with each other in a what looks like a mock cavalry battle while crying “Yoisa!” This is meant to represent plowing by farm horses. They then pick up and drop tatami mats in imitation of planting rice seedlings while singing planting songs. The ceremony ends with prayers for a bountiful year.

An offering for fertility and a good harvest. (© Haga Library)

On the second day they pound mochi rice and make it into cakes that are to be offered to the gods. This is also done in the nude. In another room, elders fashion vegetables into male and female forms that are offered to the gods.

The entrance to the sacred mountain is marked with a shimenawa rope. (© Haga Library)

From three in the morning on the third and final day, the long-awaited yama-gake begins. All the participants don head coverings fashioned from tenugui hand towels and a white costume that makes them look like ritual dolls prior to ascending the mountain. They stand in front of a small shrine and listen to the ringing of a bell to purify their hearts. An oracle known as a noriwara who takes on this position through hereditary succession is then possessed by the gods and relates the weather and expected harvest in the coming year.

This seemingly simple local ceremony is actually the origin of the hadaka-matsuri, in which participants purify their bodies in preparation for contact with the gods.

In 2023 the Kuronuma and Yawata gods descended and promised that the weather would be “fairly good” and the harvest would be “good.” (© Haga Library)

(Originally published in Japanese. Dates given are those on which the festivals are usually held. Banner photo: A scene from the Saidaiji Eyō in Okayama Prefecture. © Haga Library.)