A World of Kurosawa Posters at Tokyo Exhibition

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In April 2018, the National Film Archive of Japan opened as a newly independent institution. Formerly the National Film Center, a part of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, the NFAJ marked its new beginning with a themed exhibition on the director Kurosawa Akira, who died 20 years ago this September.

The World Discovers Japanese Film

Kurosawa is almost certainly Japan’s best-known director. Many Japanese people know of his prizes in international competitions and the respect he has drawn from directors and actors around the world. This exhibition offers visitors a visual representation of his global standing via film posters from a wide range of countries.

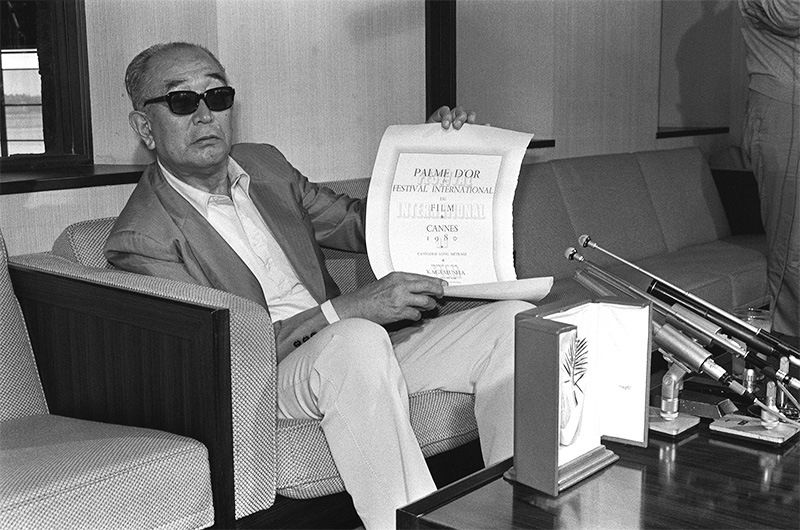

Kurosawa Akira (1910–98) at Narita Airport on May 26, 1980, after winning the Palme d’Or for Kagemusha at the Cannes Film Festival. (© Jiji)

Kurosawa Akira (1910–98) at Narita Airport on May 26, 1980, after winning the Palme d’Or for Kagemusha at the Cannes Film Festival. (© Jiji)

Kurosawa collector Makita Toshifumi has provided 84 posters for Kurosawa films from 30 countries for the exhibition. Also on display are foreign press releases, screening programs, books, and newspaper advertisements. NFAJ curator Okada Hidenori explains some of the main attractions below.

Over his career, Kurosawa directed 30 films. His career can be roughly divided into three periods. The early period comprises the 10 films from Sanshirō Sugata (1943) to Scandal (1950), when he was essentially unknown outside Japan. The middle period consists of the 13 films from Rashōmon (1950) to Red Beard (1965), when he was internationally renowned and prolific. The late period includes the 7 films from Dodeskaden (1970) to Mādadayo (1993), when Kurosawa became involved in several international coproductions.

Clockwise from top left: Wladyslaw Janiszewski’s 1960 Polish poster for Drunken Angel (1948); a 1950s Argentine poster for Ikiru (1952); a Thai poster for Red Beard (1965); Otto Kummert’s 1981 East German poster for Kagemusha (1980); a 1963 British poster for High and Low (1963).

Clockwise from top left: Wladyslaw Janiszewski’s 1960 Polish poster for Drunken Angel (1948); a 1950s Argentine poster for Ikiru (1952); a Thai poster for Red Beard (1965); Otto Kummert’s 1981 East German poster for Kagemusha (1980); a 1963 British poster for High and Low (1963).

In 1951, the year after its Japanese release, Rashōmon won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival, bringing Kurosawa’s films to the attention of cinemagoers around the world. This was the first time any Japanese film had received this level of recognition, and it showed the domestic film industry that artistic works could achieve success in international competition.

The Golden Lion award received by Rashōmon at the Venice Film Festival (bottom left) and two West German posters for the film (center). The above poster is from 1952; the lower (pictured separately at right) is a 1959 poster by Hans Hillmann.

The Golden Lion award received by Rashōmon at the Venice Film Festival (bottom left) and two West German posters for the film (center). The above poster is from 1952; the lower (pictured separately at right) is a 1959 poster by Hans Hillmann.

The 1952 poster for the West German release of Rashōmon is imbued with exoticism and the atmosphere of the “mysterious Orient.” Seven years later, a poster by rising graphic designer Hans Hillmann brings a fresh artistry to the forefront for the film’s re-release in the same country. One senses that after an initial shock, Kurosawa had become accepted and audiences had matured to his cinematographic vision.

In his composition, Hillmann eschews the straightforward techniques of run-of-the-mill posters. “The three horizontal lines that cut across the poster symbolize the distinctive narrative of the film, which consists of the different characters’ conflicting stories,” Okada says. “It demonstrates the greater understanding of Kurosawa’s work.” It is interesting to compare the nine Rashōmon posters in total from seven countries, including a Swedish one that borrows directly from a work by the artist Utamaro.

A Chaotic Battle in Bold Colors

Hans Hillmann’s 1962 West German poster for Seven Samurai (1954). Okada Hidenori is pictured giving analysis.

Hans Hillmann’s 1962 West German poster for Seven Samurai (1954). Okada Hidenori is pictured giving analysis.

There are even more posters for Seven Samurai (1954), coming from 14 countries in all. The centerpiece combines eight A0 (841 x 1189 millimeters) sheets into one giant poster, and is also by the designer Hillmann. He deploys the same five bold colors as the Olympics in his depiction of the chaotic, climactic battle between the samurai and bandits. “Hillmann shows his respect for Kurosawa by reflecting the composition of the film on paper,” Okada says.

In 1960, John Sturges remade the Kurosawa classic as the Hollywood Western The Magnificent Seven. This may have influenced a Spanish poster for Seven Samurai from 1965, which recalls a classic Western landscape. Singular posters from Thailand and Iran are also well worth seeing.

Jano’s 1965 Spanish poster for Seven Samurai (left) and an Argentine poster from 1957. Although both are in Spanish, they have different titles.

Jano’s 1965 Spanish poster for Seven Samurai (left) and an Argentine poster from 1957. Although both are in Spanish, they have different titles.