Hiroshima Historian Mori Shigeaki Heads for America

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A First US Trip for a Friend of America

On May 27, 2016, more than 70 years after Hiroshima was devastated by the world’s first atomic bombing, Barack Obama became the first sitting US president to visit the city, laying flowers before the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. After delivering a historic speech at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, he embraced an elderly hibakusha, a survivor of the bombing, creating a widely remembered image of his visit.

President Barack Obama embraces Mori Shigeaki at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on May 27, 2016. (© Jiji)

President Barack Obama embraces Mori Shigeaki at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on May 27, 2016. (© Jiji)

This hibakusha was Mori Shigeaki, an amateur historian who did years of painstaking research to identify and track down the relatives of 12 American prisoners of war who were killed by the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima. His self-financed work also led to the inclusion of the names of the 12 US servicemen in the official register of the bomb victims stored at the Peace Memorial Hall. After US government officials became aware of Mori’s labors thanks to the documentary film Paper Lanterns, released in early 2016, they worked to get him a seat at President Obama’s Hiroshima speech in May that year.

Mori, now 81, is scheduled to visit the United States for the first time at the end of May 2018. There he will travel to Boston to visit the grave of one of the fallen US servicemen with his relatives and attend a screening of Paper Lanterns at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. The filmmaker Barry Frechette, who created the documentary on Mori’s deeds, mounted a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money needed to bring the Japanese historian to American shores and open a new page in his more than four decades of research in the cause of peaceful reconciliation between one-time enemies.

We spoke with Mori Shigeaki to learn more about his work and what has driven him during the more than 40 years he has dedicated to it.

Bringing Comfort in Person

INTERVIEWER Why are you making this trip to the United States now?

MORI SHIGEAKI Thomas Cartwright was the first lieutenant who piloted the Lonesome Lady, one of the airplanes whose crews became prisoners of war. After his plane was shot down, he was taken to Tokyo for interrogation, but the other six survivors remained in Hiroshima, where they perished in the atomic bombing. Over more than twenty years I must have exchanged a hundred letters with him, and our friendship grew steadily. In 2004 I translated A Date with the Lonesome Lady: A Hiroshima POW Returns, his book on the unfortunate prisoners, into Japanese. In this way we worked together to tell people about the tragedy of war.

When Cartwright passed away in 2014 at the age of ninety, I received an invitation to his remembrance ceremony, and I really wanted to go and pay my respects. But it was going to take place in Moab, Utah, a town at high elevation that would require a two-day trip from the airport to get there, since I had to travel by car. I wasn’t sure I was physically ready for this journey, and the high transportation and lodging prices also put it out of my reach. So I sadly had to decline the invitation. I regret that to this day.

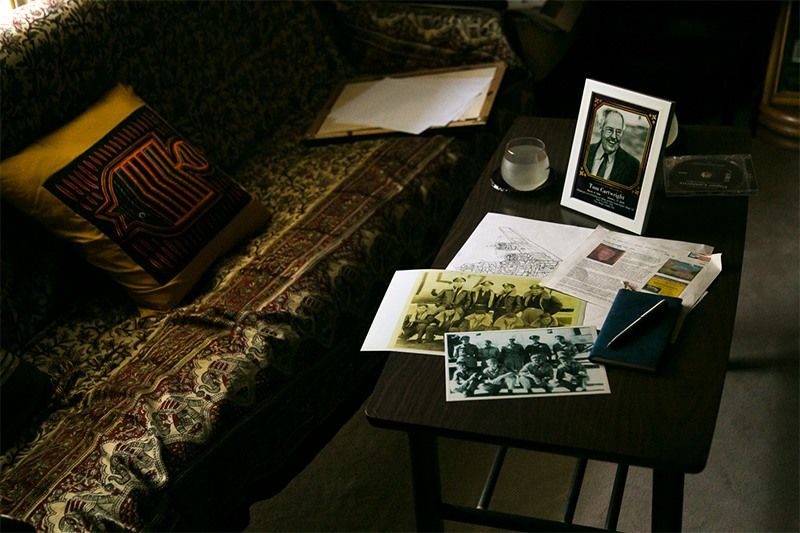

In Mori’s home, a photograph of Thomas Cartwright is on display next to materials showing the crew of the Lonesome Lady. (© Kusano Seiichirō)

In Mori’s home, a photograph of Thomas Cartwright is on display next to materials showing the crew of the Lonesome Lady. (© Kusano Seiichirō)

Most of the people who knew the crew members—their wives, siblings, and others from that generation—are gone now. One who is still with us is Connie Brissette-Provencher, sister to Normand Brissette, a Navy airman. She lives in Boston now, and meeting her is one of the purposes of my trip. When I informed her that her brother had died in Hiroshima, we began writing letters to one another. When Barry Frechette happened to learn of our correspondence, it led to his creation of the documentary movie describing my work. And this in turn led to my invitation to attend the ceremony where President Obama laid flowers before the Hiroshima cenotaph.

Connie wrote to me that Normand’s death was so hard to bear it felt like her chest was being ripped apart. Since I know just how terrible the atomic bomb has been for Connie, I aim to meet with her and give her what comfort I can. When I tell her in person that I was able to get her brother’s name and photograph included in the official register at the Peace Memorial Hall, I hope it will please her.

INTERVIEWER You never traveled to the United States as part of your efforts to identify the twelve airmen and contact their relatives?

MORI No. I’m a hibakusha myself, and my heart condition made it tough for me to just buy a ticket and head to America. My investigations ran into a wall, as all the records of the interrogations of the POWs had been incinerated in the blast. Once I managed to dig up the name of one of the men, I’d get on the phone and have an international operator go through the US phonebooks, calling the numbers given for that surname one by one, asking whether they knew a man by that name. Sometimes my monthly phone bill was more than 70,000 yen.

Anyone Would Want to Know the Truth

INTERVIEWER You must have felt some anger toward the country that dropped the atomic bomb on your city. What drove you to continue seeking information on these American victims of the bomb, and to contact their loved ones?

MORI When the bomb exploded, I was about two and a half kilometers from ground zero, walking across a bridge with two friends. When that unimaginable blast wave came, we were blown violently from the bridge into the river below. Luckily the river was a shallow one, with plenty of reeds growing in it, so I didn’t lose consciousness and drown, but it was pitch black—so dark that I couldn’t see my own ten fingers in front of me.

I made it onto the shore, where I saw a woman stumbling along on shaky legs, gasping for breath, asking where to find a hospital. She was drenched in blood and it looked as though her entire body was splitting apart. And there were many more like her following behind, heading for the local school. Then the black rain began to fall from the mushroom cloud, striking my body. The rain hurt. Only someone who has experienced the bombing will know things like this. I was just eight years old then, but I remember every detail.

Until just a few months before the bomb fell, I was attending the Seibi National People’s School, which was just around a half kilometer from ground zero. All the teachers and students there were killed, burned black in the bombing. When the air raids intensified, though, my grandmother said that if we were going to die, it was best to be together as a family, so I transferred to another school located closer to home. This saved my life. The Seibi school’s principal also survived, as he was leading some students out of the city as part of the youth evacuations taking place at the time. He later wrote that there was an American soldier’s corpse at the school as well. If I hadn’t transferred, I would likely have shared that fate. This has always made it difficult to see the deaths of these people as some event unconnected to my own life.

The Enola Gay targeted Aioi Bridge, right in the center of Hiroshima. When I learned that Americans had died right there in the blast, I could only be shocked at the fate that brought them there. Nobody knew that American prisoners of war had perished right there in Hiroshima—or that one of them, his hands tied behind his back, met his end near ground zero, right there at Aioi Bridge.

These men’s families back home knew nothing about what had happened to them: only that their husbands and sons had gone to war never to return. But I knew that anyone would want to know the truth. So I was determined to find that truth, even if it were just about one man, and to find his family to share it with them. This determination is how I got my start.

When I tracked down the relative of the last POW, he was on death’s doorstep. Since I couldn’t sign the application to get the airman registered on the list of bomb victims myself, I asked his neighbor to provide a signature on his behalf. At last, I was able to register all twelve of the Americans who died in the bombing.

The Genbaku Dome (Hiroshima Peace Memorial) stands near ground zero. Aioi Bridge is visible to the left. (© Kusano Seiichirō)

The Genbaku Dome (Hiroshima Peace Memorial) stands near ground zero. Aioi Bridge is visible to the left. (© Kusano Seiichirō)

Meeting a Thankful President

INTERVIEWER You attended the ceremony where President Obama gave his speech and placed flowers before the monument to the dead. It was then that he embraced you.

MORI I actually got the phone call from the US Embassy inviting me to the gathering just before it took place. Of course, I said, I would be honored to attend. But I could never have imagined that they would prepare me a seat right up in the front row, in front of the governor of Hiroshima Prefecture and the mayor of the city and all.

I listened with all my heart to the president’s wonderful speech. “Seventy-one years ago,” it began. I also remember the phrase, “a dozen Americans held prisoner.” And later he mentioned “the man who sought out families of Americans killed here.” I must admit that I didn’t understand all of the speech, but when I heard that, I knew he was talking about me.

When I shook hands with President Obama, I wanted to say something to him. But I was overcome with emotion, and tears filled my eyes. He saw my tears, reached around my back with his long arms, and pulled me close to him. We didn’t share any words, but our feelings were clear to one another. I am certain of this still.

As I said, I’m going to meet with Connie Brissette-Provencher during my upcoming trip to the United States. When the bomb killed Normand Brissette, her brother, he was just nineteen years old. He would never have died so young if the war hadn’t taken place. We don’t have enough words to describe all the horrors of war. There’s nothing more devastating for the people who have lived through it, for the victims, for their families left behind. This makes it all the more important to pray that atomic weapons will never again be used. To oppose war. It’s only natural to do so.

Mori Shigeaki speaks about his experience in Hiroshima and his connections with the American POWs’ families at an April 2018 screening of Paper Lanterns in Fujisawa, Kanagawa.

Mori Shigeaki speaks about his experience in Hiroshima and his connections with the American POWs’ families at an April 2018 screening of Paper Lanterns in Fujisawa, Kanagawa.

The Trailer for Paper Lanterns

Click here to support “Bring Mr. Mori to the USA,” a GoFundMe campaign organized by Barry Frechette.

(Originally written in Japanese. Interview and text by the Nippon.com staff. All photos © Nippon.com except where otherwise noted. Banner photo: Mori Shigeaki and his wife Kayoko.)▼Further reading

The Japanese Historian Honoring Hiroshima’s American Dead The Japanese Historian Honoring Hiroshima’s American Dead |  Behind the Scenes of Obama’s Hiroshima Visit Behind the Scenes of Obama’s Hiroshima Visit |