My First Encounter with Japan’s Wealth of Zeros

I first arrived in Japan on July 15, 1971, as an American college student beginning a year abroad. Though I already knew a certain amount about the country and its people, life in Tokyo, my new home, was full of surprises. One that I will never forget was the profusion of zeroes on the paper currency that I got in exchange for my US dollars. I had known that the exchange rate of the yen was ¥360 to $1, but even so I couldn’t help being taken aback to see yen bills with denominations of 500, 1,000, 5,000, and even 10,000. The price tags in stores were similarly startling.

Back in the United States I had never carried around anything bigger than a $20 bill, and at first I felt uncomfortable having and using bills with denominations in the hundreds and thousands. Even after my initial surprise wore off, they still seemed wrong somehow. Well before I came to Japan, I had learned that the country had made a remarkable recovery from the devastation of World War II and achieved great economic growth and technological advances. In some ways it had even surpassed the United States, as with its high-speed Shinkansen rail link between Tokyo and Osaka. This positive image did not fit well with the multizero bills, which seemed like the currency of a country whose economy was on the rocks.

In December 1971, less than half a year after I arrived, the exchange rate of the yen to the dollar was changed from ¥360 to ¥308, meaning a hike of about 17% in the Japanese currency’s value. And in March 1973 the post–World War II system of fixed exchange rates was scrapped and major currencies were allowed to float against each other. Over the four and a half decades since then, the exchange rate has fluctuated, but overall the yen has risen substantially. Currently, as of late 2018, it is trading in the vicinity of ¥110 to the dollar. This makes it worth over three times more in dollar terms than as of mid-1971.

Despite this rise, the exchange rate of the yen to the dollar still runs to three digits, which is highly unusual for a currency of a major country. From time to time there has been talk of redenominating the yen by a factor of 100, which would mean two fewer zeros at the end of each of the current denominations—10,000 becoming 100, 5,000 becoming 50, and so forth. But this idea has not been implemented. So many Westerners visiting Japan probably feel the same sense of strangeness as I did 47 years ago at seeing the implausibly high numbers on Japanese currency.

One Yen to the Dollar

Many years after being taken aback by Japan’s high-denomination bills I had another currency-related surprise: I learned that a yen had originally been worth one US dollar.

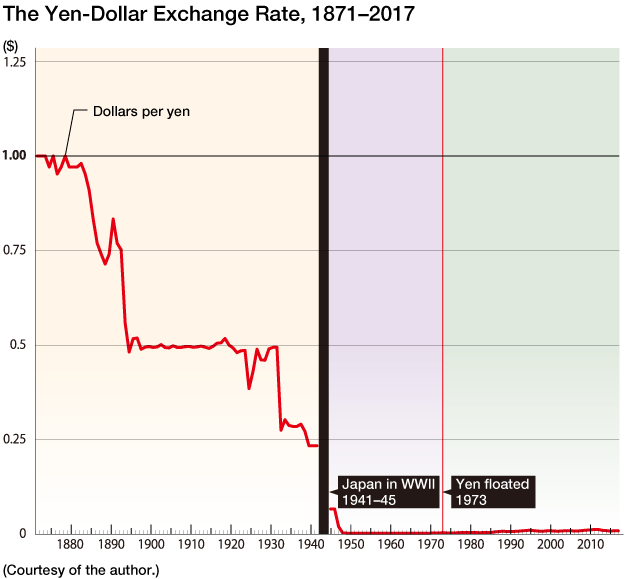

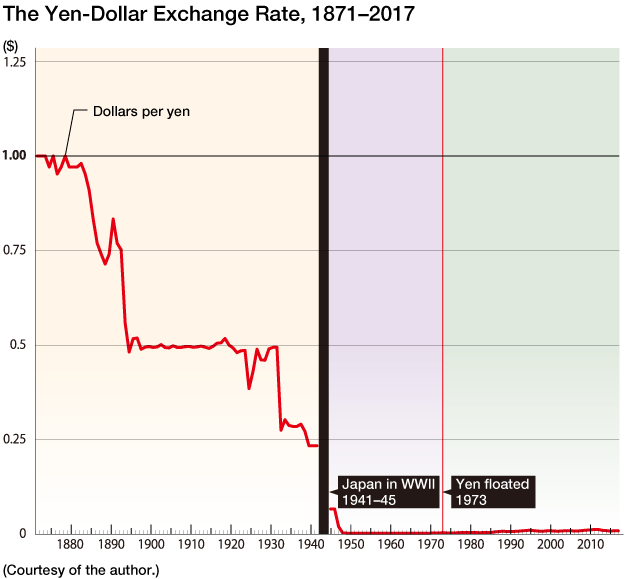

Japan adopted the yen as its currency unit in 1871. This was early in the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Japan was scrambling to turn itself into a modern nation-state that could deal with the Western powers on an equal footing. The new currency was set at a value of 1.5 grams of gold, on parity with the US dollar. In other words, the initial yen-dollar exchange rate was ¥1 = $1. As shown in the attached chart, the yen lost about half of its value against the greenback in the 1880s and 1890s, and it took another fall in the 1930s, declining to around a quarter of its original value in dollar terms. As of December 1941, when Japan went to war with the United States, the yen was worth $0.234, meaning an exchange rate of slightly over ¥4 to the dollar.

The real collapse in the yen’s value came after Japan’s 1945 defeat in the war. Tokyo and other major cities lay in ruins, the economy was in tatters, and inflation raged unchecked, robbing the currency of its worth. In 1949 a new official exchange rate was adopted: ¥360 to the dollar. The yen, which had started out in parity with the greenback in 1871 and was still worth almost a quarter of a dollar at the beginning of the 1940s, was at the end of the same decade worth a mere $0.0028, or about a quarter of a penny. The exchange rate expressed as yen per dollar, which had started at ¥1 and was in the vicinity of ¥4 as of 1941, turned into a three-digit number, ¥360, after the war.

This ¥360 = $1 peg remained in effect for over two decades, but in the 1970s the postwar Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates broke down, and the yen was floated against the dollar and other currencies. After that the yen appreciated, particularly from 1985 to 1995, when the rate went from ¥239 to ¥94 against the dollar—from three digits to two. At this point the yen’s worth had roughly quadrupled in dollar terms in comparison with the decades of the postwar peg. This was a remarkable rise—and a tremendous blow to Japan’s export industries—but it still left the yen worth only $0.0106, or a smidgen above a penny. Looking again at the exchange rate chart, we see that the red line showing the yen’s value has remained stuck close to the horizontal axis at the bottom to this day. And currently the yen-dollar rate is in the vicinity of ¥110—back in the three-digit range, meaning a yen is again worth less than a penny.

The yen may appreciate against the dollar in the future, reducing the number of digits in the exchange rate from three to two again. But no amount of ordinary currency appreciation can wipe out the drastic devaluation of the early postwar period and restore the yen to a value in the range of the dollar, thereby bringing the exchange rate down to a single digit.

The Yen as an Outlier

The vast majority of today’s Japanese have grown up in the age of three-digit yen-dollar exchange rates, which must seem perfectly normal to them. And even if they are not old enough to have personally experienced the postwar ¥360 = $1 peg, they have probably heard of it and may look at the current rate of around ¥110 = $1 as showing today’s yen to be “strong” in comparison with the decades following the war.

My perspective is different. Shortly after graduating from college in 1973, I got a job in Tokyo and have lived here ever since. But even after long exposure to three-digit yen-dollar rates and currency notes loaded with zeroes, they still feel strange to me. It seems peculiar for a country of such high international stature to have such a puny currency, worth less than an American penny. The number of foreign tourists visiting Japan has grown dramatically in recent years, and as I noted above, those coming from the United States or other Western countries are liable to have the same sort of reaction.

Subjective impressions aside, Japan is exceptional among the major advanced nations in having such a low-valued currency unit. Consider the attached table presenting the exchange rates of the currencies used by the 36 economically advanced democracies belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The table lists these 20 currencies in the order of their value expressed in US dollars.

The Yen and Other OECD Currency Units Ranked by Value

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, November 2018 (projected exchange rates for 2018 from online statistical annex).

Note: Blue highlighting marks the currencies used by members of the Group of Seven other than Japan. G7 members France, Germany, and Italy use the euro.

Japan may have the second-biggest economy in the OECD, but its currency unit is near the bottom of the list, at number 17 out of 20. Within the Group of Seven, meanwhile, Japan places last in terms of currency unit value. The other six members of this select group all use units with values among the top five in the OECD listing: the British pound, the euro—used by G7 members France, Germany, and Italy—the US dollar, and the Canadian dollar. The yen is not even in the same league as these four other G7 currencies, whose values cluster in the relatively narrow band of $0.75–$1.30.

The Chinese yuan (renminbi) is not shown in the table, since China is not a member of the OECD. The yuan is currently worth about $0.14; if included, it would be number 12 out of 21, taking a place just below the Danish krone and above the Norwegian krone and the Swedish krona. In other words, it has a value in the same league as the three Scandinavian countries. And one US dollar fetches about seven yuan—a single-digit exchange rate.

I realize, of course, that these currency unit values, high or low, have no inherent connection with the economic scale or soundness of the countries that use them. But the yen’s low international ranking is certainly in sharp contrast to the lofty position of its economy.

Introducing the “Rin”

Above I wrote of the peculiar proliferation of zeros in Japan’s currency, the yen, which was launched in 1871 at parity with the US dollar but is now worth less than a US penny. The yen, I noted is also an outlier by comparison with the currency units of other major economic powers.

In view of this disparity, I think Japan should seriously consider redenominating its currency by a factor of 100. Rather than introducing a “new yen” to supersede the present one, I would propose adopting a totally new currency unit worth ¥100, leaving the yen in place as a fractional unit corresponding to the US cent. My suggested name for the new unit is “rin,” about which more below.

Let us take another look at the OECD currency rankings presented in the first half of this article, this time using the rin instead of the yen as Japan’s unit.

The “Rin” and Other OECD Currency Units Ranked by Value, November 2018

Note: Blue highlighting marks the currencies used by members of the Group of Seven other than Japan. G7 members France, Germany, and Italy use the euro.

The rin places fifth among the OECD currencies, just after the Swiss franc, and its value is in the same dollar-centered range as the other G7 units. This is surely a more appropriate position for Japan’s currency.

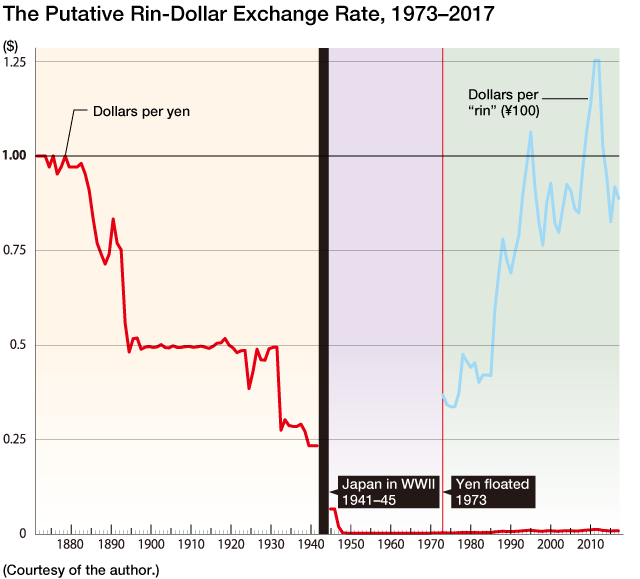

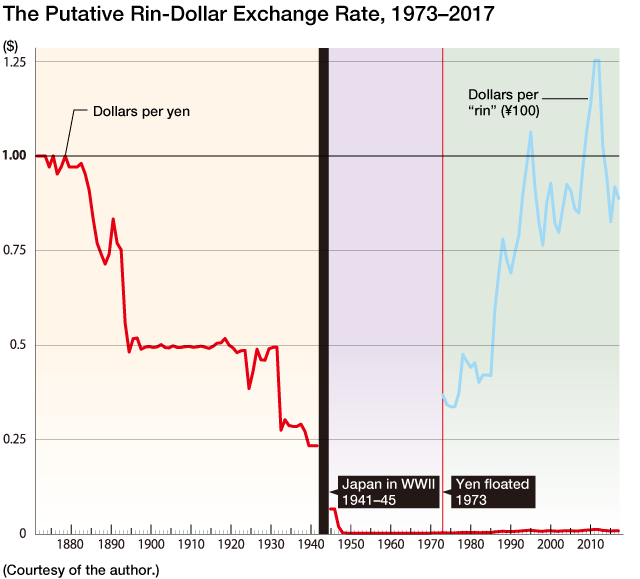

Let us also take a look at a revised version of the historical yen-dollar exchange rate chart presented in the previous half of this article.

I expect that tourists from abroad, particularly those from the West, would quickly familiarize themselves with the rin; they would be able to grasp prices in shops and restaurants without referring to electronic or paper conversion tools. By the same token, Japanese visiting the United States or other Western countries would know that currencies like the dollar and the euro were in the same general range as their own rin.

What about the Chinese, who now account for around a quarter of Japan’s international visitors? The exchange rate between the Chinese yuan and the Japanese yen is now about ¥16 to the yuan. So Chinese tourists shopping in Japan need to divide prices by 16 to get the equivalent amount in their own currency. Dividing by 16 is not something many people can do in their heads! Were Japan to adopt the rin, multiplication by 8 would give the approximate value in yuan. This, I daresay, would be considerably easier. And at first glance (before conversion into yuan), Japanese prices would look invitingly low rather than absurdly high. For example, instead of a price tag of ¥10,000 on an item costing about 800 yuan (roughly $110), shoppers would see a tag marked R100.

Incidentally, the Chinese yuan sign, ¥, is exactly the same as the Japanese yen sign. So when Chinese visit Japan, they are all the more likely to be startled when they see a price like ¥10,000, which is bound to register as meaning 10,000 yuan (well over $1,000) at first glance. A rin sign, whether a simple “R” or a stylized version thereof, would not induce this momentary misconception.

Why “Rin”—and When?

By adopting a new name for the new currency unit, Japan will be able to continue using the yen as its fractional (1/100) unit, like the cent in countries whose principal unit is the dollar or the euro. The yen coins and bills now in circulation will keep their value, and all contracts, securities, and other legal documents with amounts in yen will remain valid; there will be no need to rewrite them. And issuing new coins and bills with the same specifications (sizes, colors, designs, and coin weights) as their yen equivalents should ease the transition for the general public—and for the country’s ubiquitous vending machines.

My candidate for the new currency’s name is “rin,” written in Japanese with the kanji 輪, whose primary meaning is “ring.” This gives it a certain similarity to “yen,” written with the character 円 (en), meaning “circle.” And unlike “yen,” it has no homonyms in English—or, as far as I know, in any major Western language. Another candidate that some proponents of redenomination have suggested is “ryō,” the name of a gold-based currency unit used for some centuries before the yen was adopted. But this word is difficult for many English speakers to pronounce in a way that approximates the Japanese—a single syllable with the glided y sound heard in “cue” (kyoo). They are liable to say “REE-oh,” which sounds very different. “Rin” should be easy for speakers of English and other major languages to say in a way that Japanese can readily understand.

As for the timing of the shift, it would have been good to launch the rin in advance of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics—particularly given the “ring” meaning of my proposed character—but that seems impracticably soon. How about 2021, the sesquicentennial of the yen’s adoption?

The new currency will doubtless seem strange at first to its Japanese users. But most international visitors will surely find it more comfortable to deal with than the yen. And for the first time since the nineteenth century, Japan will have a currency unit close in value to the US dollar, the de facto global standard around which other major currencies are clustered.

If Japan redenominates its currency, adopting the rin or some other new unit equal to ¥100, the yen will be demoted, so to speak, to fractional-unit status. Even so, ¥1 coins are likely to remain in wide use at supermarkets and other shops where prices are often set in units of yen.

So by all means let us keep the yen for everyday use. But let it retire from service as Japan’s main currency unit, replaced by a rin that has a value more in keeping with the country’s international standing—and that is less profligate with zeros!

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo © Happyphoto/Pixta.)