Japanese Art and Artisanship’s European Debut

The first products of Japanese art and artisanship to capture extensive demand in Europe were ceramics. Chinese porcelain had become popular with members of royalty and the aristocracy across Europe, but the collapse of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) interrupted China’s exports of ceramics. Japan’s Nabeshima clan, which controlled what is now Saga Prefecture, moved to capitalize on the opportunity. The clan fortified its already well-established ceramic industry and began exporting large volumes of porcelainware to Europe under the names Nabeshima, Imari, and Kakiemon. It exported some 1.9 million items of porcelainware over the 32 years from 1652 to 1683. Japan’s porcelain exports subsequently declined sharply, however, as producers in Meissen, Germany, and Sèvres, France, absorbed the Chinese and Japanese production techniques and began supplying high-quality porcelain made with locally mined kaolin.

Imari porcelain, around 1680, Sèvres—Cité de la céramique (Sèvres City of Ceramics, photo © World Imaging).

Imari porcelain, around 1680, Sèvres—Cité de la céramique (Sèvres City of Ceramics, photo © World Imaging).

Lacquerware is another product category where works of Japanese art and artisanship earned European favor in the mid-seventeenth century. The European Christian missionaries in Japan took a liking to Japan’s lacquerware, especially items embellished with maki-e gold-sprinkled decoration. They employed lacquerware in such items as frames for religious paintings and bible stands. Others perceived more-worldly potential in Japanese lacquerware, and the Dutch East India Company was soon handling a large volume of exports to Europe. So ubiquitous did the imports become that “japan” became a common term for lacquerware, irrespective of origin.

Ukiyo-e Wrapping Paper

Japanese refined the woodblock printing technology that engendered the multicolored prints known as ukiyo-e around 1765. Isaac Titsingh (1745–1812), who headed the Dutch trading house in Nagasaki, dispatched the first exports of ukiyo-e prints to Europe. Later the German botanist and physician Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866), who cared for Nagasaki’s Dutch contingent, took home several ukiyo-e by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) when he repatriated.

A description of a salon decorated with Japanese artwork appears in an early entry in the Journal des Goncourt (1851–96). That journal, coauthored by the French brothers Edmond (1822–96) and Jules de Goncourt (1830–70) and by Edmond after the death of Jules, is a revealing chronicle of its era. The description cited above confirms that a Japanese aesthetic had taken hold in France in the Second Empire (1852–70). France’s love affair with Japanese artistry gained momentum with the extensive Japanese exhibits at the Paris Exposition (Exposition Universelle) of 1867 and was still waxing when Paris again hosted an international exposition in 1878.

A lot of ukiyo-e reached France, curiously, as packaging. Japan was awash with ukiyo-e in the mid-nineteenth century, and discarded prints frequently became packing material for ceramics and other items destined for Europe. Thus did the graphic artist Félix Bracquemond (1833–1914) discover drawings by Hokusai in 1856 on paper packing in a box of Japanese ceramics. The works were on pages from the multivolume collection Hokusai manga (Sketches by Hokusai).

Bracquemond was startled at their sophisticated artistry and called attention to the drawings. Six years later the orientalist Madame Desoye and her husband opened Paris’s first shop devoted to imports of Japanese artwork. That shop attracted a clientele of artists and others who figured prominently in fostering French and European interest in Japanese aesthetics.

A work from Volume 15 of Hokusai manga, published in 1878 by Tōhekido. (Photo courtesy of the National Diet Library.)

A work from Volume 15 of Hokusai manga, published in 1878 by Tōhekido. (Photo courtesy of the National Diet Library.)

Ukiyo-e famously gained global stature as an important art form after winning recognition from prominent painters in Europe. Claude Monet (1840–1926) hung several ukiyo-e in his house in the Paris suburb of Giverny. Edmond Goncourt, meanwhile, published a collection of ukiyo-e by Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806) in 1891 and another of ukiyo-e by Hokusai in 1896, both at the urging of the Japanese art dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906).

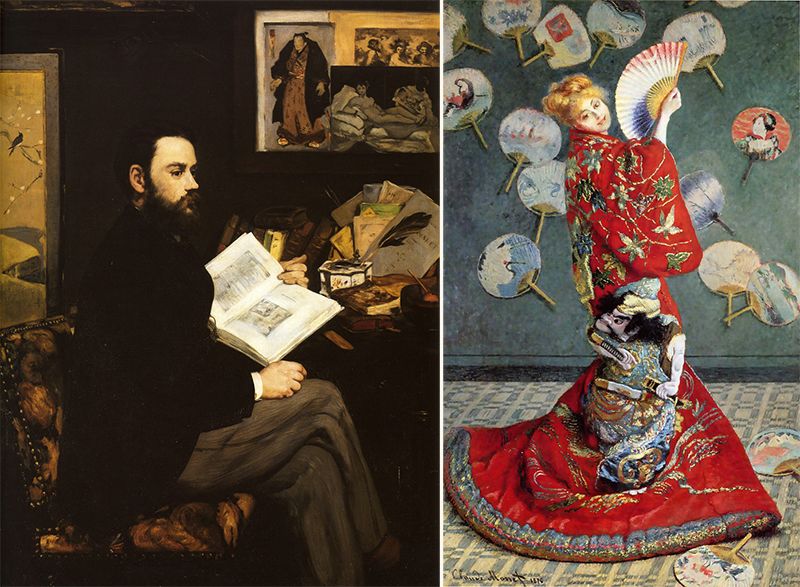

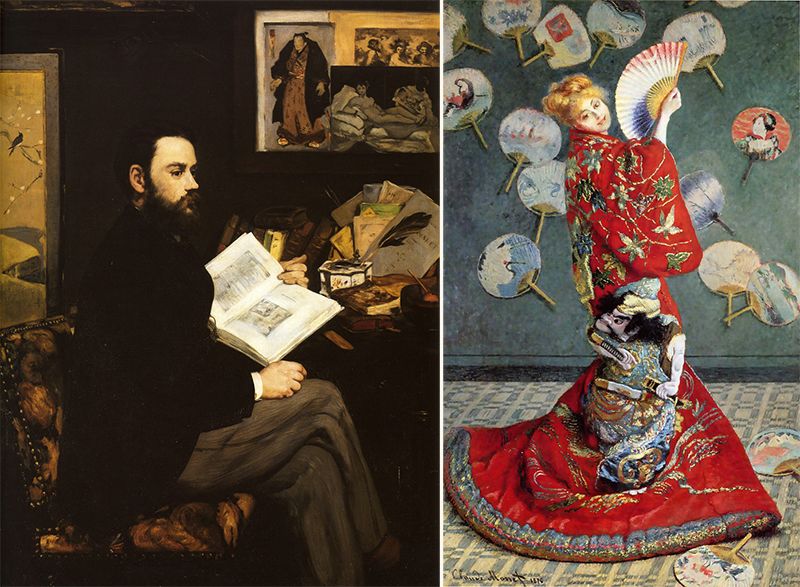

Other modes of Japanese art also captured the attention of leading impressionist and postimpressionist painters in Europe. A painted Japanese screen is prominently visible in the background in the Portrait of Emile Zola by Edouard Manet (1832–83), and Claude Monet exhibited a painting of his wife in Japanese costume at the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876. Among the other prominent painters who absorbed powerful influence from Japanese art were Vincent van Gogh (1853–90), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901).

Left: Edouard Manet (1832–83), Portrait of Emile Zola, 1868, Musée d’Orsay; right: Claude Monet, Madame Monet in Japanese Costume (La Japonaise), 1876, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Left: Edouard Manet (1832–83), Portrait of Emile Zola, 1868, Musée d’Orsay; right: Claude Monet, Madame Monet in Japanese Costume (La Japonaise), 1876, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Birth of Japonism

The French art critic Philippe Burty (1830–90) coined the term Japonisme (English: Japonism) to describe the influence of Japanese aesthetics in the West. That term is subject to diverse interpretations, but we will do well here to employ the definition offered by the art historian Mabuchi Akiko (1947–) in Japonizumu—genso no nihon (Japonism—Mysterious Japan, 1997). Mabuchi’s definition is as follows:

“‘Japonism’ refers to the Japanese influence on European and American art in the latter half of the nineteenth century. That influence extended to every genre of art. We find examples of it in painting, sculpture, printmaking, drawing, crafts, architecture, fashion, and photography, and also in drama, music, literature, and even cuisine.”

The Tokyo-based Society for the Study of Japonisme, headed by Mabuchi, has issued the book Japonizumu nyūmon (An Introduction to Japonism), which characterizes the rise and fall of Japonism as follows:

“We can regard Japonism in the context of exoticism as a facet of nineteenth-century orientalism. It was a powerful stimulus that reshaped values and technical approaches in numerous genres of Western art across half a century and then ceased to fulfill that role as it lost its freshness.”

France was where Japanese artistry exerted its greatest influence in the West in the nineteenth century, and the French were proactive in ingesting aesthetic input from Japan. The art collector Henri Cernuschi (1821–96) traveled to Japan from France with the art critic Théodore Duret (1838–1927) in 1871; another French collector, Émile Étienne Guimet (1836–1918), made the trip in 1876; and the art dealer Samuel Bing (1838–1905) traveled to Japan from France in 1880. All three visits resulted in the purchases of large amounts of Japanese artwork, which fueled the Japonism boom back in France.

The Japanese were equally proactive in nurturing Japonism in Europe. Japan was a high-profile presence, for instance, at the international expositions in Paris in 1867 and 1878. The shogunate and the domains of Saga (today’s Saga Prefecture, then controlled by the Nabeshima clan) and Satsuma (today’s Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures) enlivened the 1867 exposition with extensive exhibits of ukiyo-e, hanging scrolls, kimono, maki-e lacquerware, ceramics, and other items. After the close of the exposition, moreover, the Japanese sold all of the exhibition items to eager buyers from Europe and elsewhere.

At the 1878 exposition, the exhibits staged by Japan’s newly minted Meiji government included a farmhouse erected in Paris’s Trocadéro Park. Visitors thronged the farmhouse and delighted in the accompanying introduction to Japanese lifestyles. This was the acme of France’s Japonisme.

Left: The Japanese delegation to the 1867 International Exposition in a photo from Le Monde Illustré;right:the 1878 exposition catalog of Japanese exhibits. (Both photos courtesy of the National Library of France.)

Left: The Japanese delegation to the 1867 International Exposition in a photo from Le Monde Illustré;right:the 1878 exposition catalog of Japanese exhibits. (Both photos courtesy of the National Library of France.)

Le Japon Artistique

Bing was a seminal force in propagating Japonism through his work as an art dealer, critic, and journalist. Especially influential was the monthly magazine that he published in French, English, and German as Le Japon Artistique. The magazine, which featured premium-grade paper and printing, was full of color reproductions and carried articles about different genres of Japanese art, such as ukiyo-e, metalwork, ceramics, architecture, and kabuki. It spanned 36 issues from 1888 to 1891. Bing offered the following paean to the Japanese artistic sensibility in the fifth issue of Le Japon Artistique, published in 1888: “The Japanese artist knows well that nature subsumes the most important elements of all phenomena. Accordingly, he or she believes that everything—even something so small as a single blade of grass—occupies an identifiable place in the conceptual framework that underlies the creative process.”

The May 1889 issue of Samuel Bing’s monthly magazine Le Japon Artistique. (Photo courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections.)

The May 1889 issue of Samuel Bing’s monthly magazine Le Japon Artistique. (Photo courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections.)

Bing’s comment resonates with praise for Japanese ceramics by the British art critic John Robinson. Robinson wrote insightful commentary about Chinese and Japanese ceramics, and he was especially praiseful of Japanese works in regard to the purity of the pictorial motifs employed, the straightforwardness and elegance of the geometry, and the quality of the craftsmanship.

The praise from Bing and Robinson presages the admiration that Japanese manufactured goods would earn in the latter half of the twentieth century. We can thus regard Japonism as an expression of the same cultural traits that underlie the high-quality manufacturing of monozukuri.

Bing’s chief object in launching and publishing Le Japon Artistique was to broaden the market for Japanese art. The magazine yielded the additional benefit, however, of awakening European artists to the breadth and appeal of the Japanese artistic sensibility. We note with interest that Bing christened the publication “Artistic Japan” and not “Japanese Art.” He sought to highlight the aesthetic values that permeate Japanese life, and he succeeded impressively.

The Wilting of the Blossom

Japonism’s subsequent influence on European art and design is evident in the work of members of the Les Nabis group of postimpressionist painters, in European decorative prints and posters, and in Art Nouveau ceramics and architecture. We detect that influence in the insect and floral motifs employed by the Nancy-based glass artist Émile Gallé (1846–1904) in his Art Nouveau creations, and we encounter carp and blossoms à la Hokusai in elaborate glass vessels from the Paris glass-making studio run by François-Eugène Rousseau (1827–90).

Interestingly, the foremost US evocation of Art Nouveau was in the Tiffany lamps of Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), the son of Tiffany and Company founder Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902). And the Paris branch that Tiffany and Company opened in 1850 had begun selling items in the 1860s featuring Japanese motifs. Dragonflies, flowers, and other subjects rendered in Japanese style appeared on such Tiffany products as coffee pots, teapots, and milk and sugar bowls.

Japonism spread beyond Western Europe and influenced arts and crafts in Eastern Europe and Russia, North America, and Australia and New Zealand. The overt enthusiasm for Japanese aesthetics, however, had waned substantially by the 1930s. As Japan flexed its military muscle, people came to associate the nation more with bald aggression than with sensitive artistry. Japonism’s blossom had wilted.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on July 2, 2015. Banner photo: Claude Monet’s house in the Paris suburb of Giverny.)

Imari porcelain, around 1680, Sèvres—Cité de la céramique (Sèvres City of Ceramics, photo © World Imaging).

Imari porcelain, around 1680, Sèvres—Cité de la céramique (Sèvres City of Ceramics, photo © World Imaging). A work from Volume 15 of Hokusai manga, published in 1878 by Tōhekido. (Photo courtesy of the National Diet Library.)

A work from Volume 15 of Hokusai manga, published in 1878 by Tōhekido. (Photo courtesy of the National Diet Library.) Left: Edouard Manet (1832–83), Portrait of Emile Zola, 1868, Musée d’Orsay; right: Claude Monet, Madame Monet in Japanese Costume (La Japonaise), 1876, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Left: Edouard Manet (1832–83), Portrait of Emile Zola, 1868, Musée d’Orsay; right: Claude Monet, Madame Monet in Japanese Costume (La Japonaise), 1876, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.