Abdication and the Japanese Emperor as a Pacifist Symbol

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Concern Over Succession

Emperor Akihito, who is now 82, indirectly expressed a desire to abdicate in favor of his son Crown Prince Naruhito in a video message broadcast across Japan on August 8, 2016.

It was the most startling imperial pronouncement since his father Hirohito (known posthumously as Emperor Shōwa) told the Japanese people via radio on August 15, 1945, that the country had unconditionally surrendered to the Allied Powers. The Imperial House Law, which governs matters relating to the imperial family, does not allow for abdication, stating that the crown prince succeeds after the death of the emperor.

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō stated that he would “deeply consider” the emperor’s words. His government is adopting a cautious stance, though, rather than seeking to immediately amend the law. One factor behind this is the postwar Constitution, which forbids the emperor’s involvement in politics; if the government appeared to be swayed by the wishes of the emperor, it would raise the question of unconstitutionality.

This subtle issue led Emperor Akihito to frame his announcement in terms of his thoughts “as an individual.” As he senses his own aging, it is likely that he feels great concern over the role of the emperor as the symbol of a pacifist country, which he and his father have taken on throughout the postwar era, and the passing on of this role to future generations.

Options for Abdication

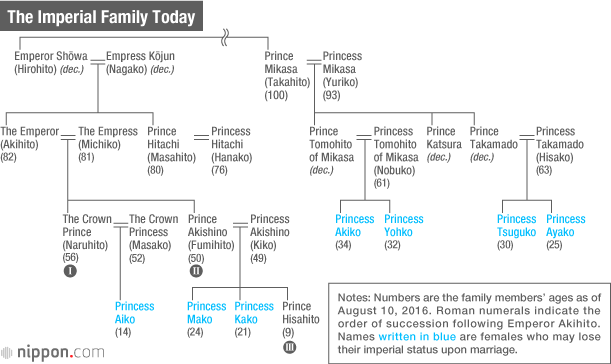

Defenders of tradition describe Akihito as the 125th emperor in an unbroken patrilineal line. Under the Imperial House Law, female members of the family lose imperial status when they marry outsiders. Beginning in 1969, nine successive children born into the family were girls, and there was no potential male successor beyond the generation of Crown Prince Naruhito and his brother Fumihito, Prince Akishino. This changed with the 2006 birth of Fumihito’s son—Prince Hisahito, the first baby boy in the imperial family for 41 years. Even so, the family is shrinking and there is a very real possibility that the young Prince Hisahito could become an emperor with no eligible successors if he ascends to the throne after the deaths of Akihito, Naruhito, and Fumihito.

Another issue is the adjustment disorder that Crown Princess Masako suffered in adapting from the freedom of a high-power diplomatic career to the antiquated traditions and customs of the imperial household. She rarely appears at official functions, and the crown prince and princess have not been seen as properly fulfilling their duties. Akihito has been concerned for many years whether Naruhito will be able to perform the symbolic role expected of the emperor.

At 56, the crown prince is now one year older than when Akihito was when he became emperor. It is natural for Akihito to wish to look ahead to the future by passing responsibility on to the crown prince while he is still alive and supporting him as he gains experience.

Establishing a timetable for ceding the throne first from Emperor Akihito to Crown Prince Naruhito and from him to Fumihito would ensure that the imperial family could respond to ever-increasing duties, as well as disasters and other national crises. Perhaps this could be based at first around a three-man system with Akihito and Fumihito supporting Naruhito.

In Europe, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands abdicated in 2013 and was succeeded by her son Willem-Alexander. King Albert II of Belgium stepped down in favor of his son Philippe in the same year, while King Juan Carlos I of Spain abdicated in 2014, passing the throne to his son Felipe VI. These long-standing friends and counterparts of Emperor Akihito passed the torch on to the next generation, perhaps feeling that their era was over and—whether they liked it or not—that their sons’ era had begun.

No Attempt to Address the Shrinking Imperial Family

At an August 2015 ceremony commemorating the war dead, exactly 70 years after the end of World War II, Emperor Akihito made unprecedented references to “feelings of deep remorse over the last war.” This was seen as a response to a sense of crisis over Japan’s status as a pacifist country amid a growing shift toward nationalistic revisionism in the country’s politics.

At the same ceremony, however, the emperor became confused about the order of events and almost began his speech when it was time for the silent prayer. This may have been an episode that heightened his concern about aging, leaving him to brood about the limited time he had left.

The past decade has seen suggestions that the problems of the shrinking imperial family could be addressed by amending the law to allow female succession or to allow female members to remain part of the family after they marry. These have not been taken up, however, due to opposition based on a desire to maintain the patrilineal tradition. As the present Abe cabinet also supports this tradition, there has been no recent attempt to move forward with legal amendments.

If the cabinet were to take action, it would most likely aim to restore imperial status to the branches of the imperial family that lost it when the family was reduced in size after World War II. Emperor Akihito might be reluctant, however, to seek successors among distant blood relatives who were removed from the family 70 years ago.

The Emperor’s Efforts

In the charred wreckage of a Japan defeated in World War II, the emperor’s role transformed from head of state to, as defined in the new Constitution, “a symbol of the State and of the unity of the People” under a democratic government.

There was a strong sentiment among some of the Allied nations that Hirohito should be tried as one of the Axis leaders. Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers Douglas MacArthur decided to defend the emperor, however, to ensure that the occupation of Japan would run smoothly. He pressed a new draft Constitution on Japan, which included the eternal renunciation of war alongside a ceremonial and spiritual role for the emperor, allowing him no political power. By doing so, MacArthur was able to persuade more hardline countries and preserve the world’s oldest monarchy. As a priestly king, said by legend to be a descendant of the sun goddess, the postwar emperor was expected to pray for peace and citizens’ well-being. The imperial family also found its purpose in fulfilling this role.

Following the death of Emperor Shōwa in early 1989, Emperor Akihito played his symbolic role from the start by making journeys of reconciliation to express regret in Asian countries and the West for the suffering caused by Japan’s wars of aggression. He has visited foreign battlefields, traveling to Saipan in 2005, to Palau last year, and to the Philippines—one of the main combat zones of the Pacific War—in January of this year. He has mourned the dead on many occasions in Okinawa, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and other Japanese sites. He has also worked to bring cheer to disaster victims, the disabled, and other socially vulnerable people.

At the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, the emperor was receiving treatment for cancer and coronary disease. Nonetheless, he toured the areas devastated by the tsunami to pray for the souls of the nearly 20,000 victims and offered encouragement to those residents of Fukushima Prefecture who could not return to their hometowns due to radioactivity caused by the nuclear accident. These actions deepened the love and respect for him from citizens.

They also heightened the surprising nature of the emperor’s sudden announcement on August 8. While there is public understanding, many are unsure how to take the news in.

Emperor Akihito’s speech gives some insight into the burden he has carried in doing his utmost to embody a highly abstract and complicated role. He has tried to visit every corner of the country, including remote islands, “to stand by the people, listen to their voices, and be close to them in their thoughts.” He looked back on those travels with the following words.

“I was made aware that wherever I went there were thousands of citizens who love their local community and with quiet dedication continue to support their community. With this awareness I was able to carry out the most important duties of the Emperor, to always think of the people and pray for the people, with deep respect and love for the people. That, I feel, has been a great blessing.”

Concerning his creeping aging, he confessed, “I am worried that it may become difficult for me to carry out my duties as the symbol of the State” and of the unity of the people, as spelled out in the Constitution.

Abdication and the Pacifist Constitution

Over the lengthy span of Japanese history, it has not been uncommon for emperors to abdicate and continue to wield political power. For this reason—and to prevent turmoil surrounding the succession, such as forced abdication due to embroilment in politics—abdication has not been legally permitted since the Meiji era (1868–1912).

However, prior to that era, abdication was quite unexceptional. About half of all emperors since ancient times ended their reigns by stepping down. In that sense, the obstacles to legal amendment are much lower than for an unprecedented change to matrilineal succession. Yet the Imperial House Law is solidly and consistently based around the condition that succession can only take place with the death of the emperor. It will be necessary to define the status of the former emperor (known in Japanese as dajō tennō or jōkō) and amend a host of related legislation. Many issues will arise, such as the form of regulations for allowing abdication, the relationship between the former and current emperors, and how to reorganize traditional court ritual and protocols. The task will not be an easy one. Given the long period needed to comprehensively reform legislation related to the imperial family, it may not be completed in time.

Prime Minister Abe said that he would “deeply consider” the emperor’s words. There is some speculation that he will establish an expert committee this autumn to discuss the matter.

At the same time, Abe has a long-standing desire to amend the Japanese Constitution, which he sees as having been imposed by occupying forces in the early postwar years. The ruling parties’ victory in the House of Councillors election in July means that—together with favorably inclined opposition lawmakers—they now have the two-thirds majority in both the upper and lower houses needed to move forward with constitutional change. However, the unexpected weighty “suggestion” by the emperor throws a spanner in the works just when it seemed that the prime minister could move ahead toward amendment. It throws off his political timetable of completing this task by 2018, when his term as president of the Liberal Democratic Party comes to an end and he must step down as prime minister.

With this connection to Japan’s pacifist Constitution, which has remained unchanged for 70 years, the debate surrounding Emperor Akihito’s abdication will continue to draw great interest both domestically and internationally.

(Originally written in Japanese on August 10 and published on August 16, 2016. Banner photo: People watch the emperor’s video message on a giant screen in Osaka on August 8, 2016. © Jiji.)