Rwandan Genocide Behind Career in Disease Research

Health Education Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On a Mission to Cure Infectious Disease

“It’s your dream.” “Don’t give up.” “You can do it.”

Juntendō University’s François Niyonsaba says he has overcame countless difficulties during his life by repeating these phrases to himself. He defied a tragic destiny, surviving a childhood plagued by starvation and sickness to achieve success in his field.

There is a grimness his words. “In developing countries in Africa and elsewhere, infectious diseases claim around 3 million lives a year. My dream is to develop drugs to overcome such diseases,” he says.

Niyonsaba’s current fields of research are global contagious disease, skin immunology, and allergology. These are all connected with his contributions to the treatment of contagious diseases through the study of antimicrobial proteins in the skin.

War Turned World Upside Down

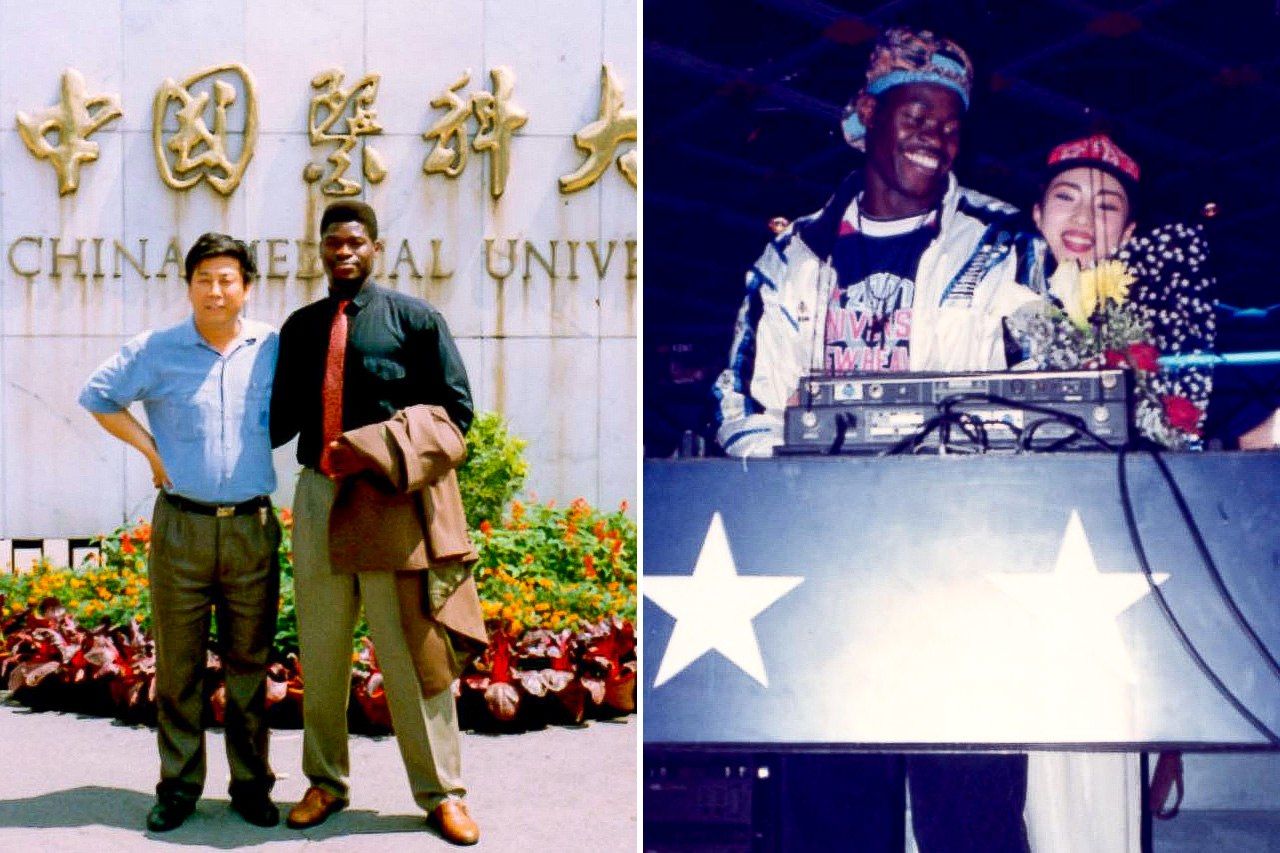

Niyonsaba began studying medicine in China in 1988. He studied the Chinese language at Beijing Foreign Studies University and Chinese medicine at China Medical University in Shenyang. In 1994, after qualifying as an orthopedic plastic surgeon, he was preparing to return to Rwanda to practice medicine in 1994 when the Rwandan Civil War broke out. Conflict between Hutus and Tutsis was compounded by a cycle of hate, not only between Hutus and Tutsis, but also among members of the same ethnic group, that saw neighbors massacre one another throughout the nation. Niyonsaba cancelled his plans to return home. As the Rwandan government’s support for citizens studying overseas dried up, he worked as a DJ to support his research.

At left, at China Medical University in 1994; at right, in the Shenyang nightclub where he spun records as a DJ to support himself in 1995. (Courtesy of François Niyonsaba)

Two years later, Niyonsaba—still in China—received a letter from his brother saying that 50 of his relatives in all, including his mother, had died. The massacre by the Rwandan Patriotic Front had claimed the lives of 10 of his 16 siblings.

“I asked myself how God could be so cruel. However, I was lucky to have survived. The experience made me feel that I must survive at all costs,” he says.

Some time later, Niyonsaba was offered a job as a doctor by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, which encouraged him to return to Rwanda. However, he says he could not bring himself to work for the organization that killed his family. In 1998, a Japanese acquaintance helped him travel to Japan. While Niyonsaba’s initial plan was to immediately seek refuge in France, based on referrals from acquaintances and recommendations from researchers, he instead decided to resume his medical research at Juntendō University.

“If I had gone to France as a refugee, I would have been forced to abandon my dream of becoming a doctor or a researcher. Japan and the Japanese people saved me and changed my life,” he says.

Saving as Many Lives as Possible

However, in Japan, he could not forget his mother or the siblings and friends he had lost in the civil war. Despite his deep sadness, he was overcome by a sense of purpose to save as many lives as he could through the power of medicine.

Rwandan refugees leave camps in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) near Goma to return to their country in 1996. (© AFP/Jiji)

Rwandans fleeing from the civil war fell victim not only to massacres and war, but also to infectious diseases that spread due to the unavailability of medical care. In developing countries, tuberculosis, AIDS, and malaria claim more victims than lifestyle diseases, injuries, or cancer. After some consideration, Niyonsaba decided to change his field of specialization, reasoning that infectious disease research would enable him to save the lives of more Africans. After obtaining a doctorate from Juntendō University, Niyonsaba began working at the university’s Atopy Center, where was significantly involved in research on antimicrobial proteins.

Ever present on the skin of living creatures, antimicrobial proteins behave like antibiotics, increasing rapidly when they detect viruses or bacteria. The chief aim of Niyonsaba’s research was to determine whether this property could be used to treat other infectious diseases.

In 2022, Niyonsaba discovered that autophagy, the process by which cells recycle unneeded proteins, is suppressed in patients with atopic dermatitis. He identified a substance that would boost immunity by restoring this recycling function.

“I want to look at how we can induce antimicrobial proteins to boost immunity in humans, and make it possible to use such drugs to fight various illnesses in clinical settings,” he says.

Rescued from Poverty by Education

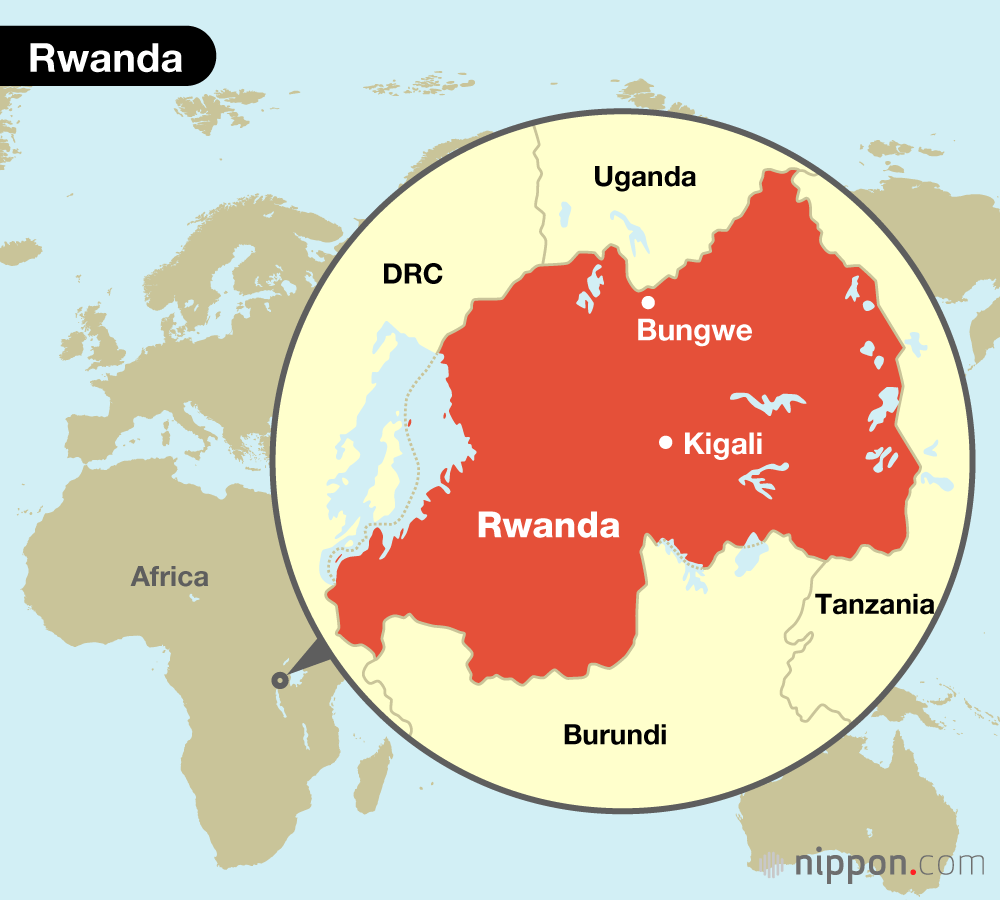

Niyonsaba hails from Bungwe, a small town near the border with Uganda in northern Rwanda, located 50 kilometers north of the capital, Kigali. Raised in a household that mostly survived on agriculture, he often went hungry as a child. If he received potatoes or milk one day, he counted himself lucky.

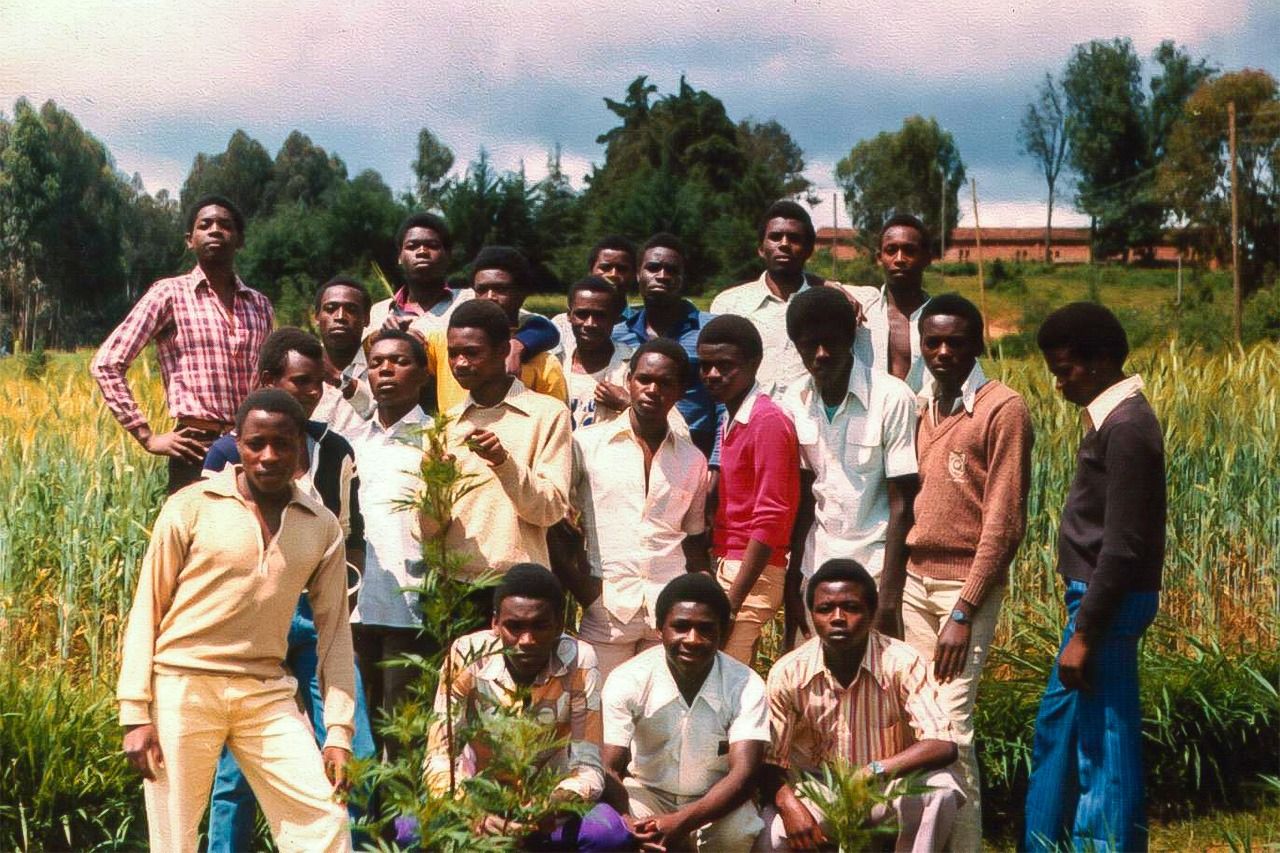

Niyonsaba’s father wanted him to go to school to escape poverty, and allowed him to attend classes on the condition that he gather water and take care of the family’s livestock. In 1982, Niyonsaba was selected by the government country to study at Academie De La Salle, a boarding school in neighboring Byumba. His parents sold three cattle each year to pay for his tuition. It was the beginning of a life of learning to realize his dreams. At middle school and high school, he devoted himself to the study of math, physics, biology, and chemistry, all of which he excelled at.

Niyonsaba (third from the left at rear with his arm on his friend’s shoulder) near his high school in 1985. (Courtesy of Francois Niyonsaba.)

While studying in Beijing in 1989, he witnessed the Tiananmen Square massacre, in which prodemocracy student demonstrators clashed with the authorities. The university was thrown into chaos, and students faced intense suppression, but he did not abandon his studies.

“I wanted to escape poverty. By studying hard, I could increase my options. I also had an obligation to do my best for my family who had supported me,” he says.

Overcoming Ignorance

The main focus of infectious disease control is education. Unable to access proper education, many citizens in developing countries do not know how to deal appropriately with infectious diseases. HIV is not present in sweat, saliva, or tears, and cannot be passed on by hugging or kissing, but Rwandans are not taught this. Instead, prejudice and discrimination are rampant, and HIV is seen as an abhorrent disease.

When Niyonsaba returned to Rwanda in 2011, he visited his high school friend who had developed AIDS and weighed only 30 kilograms, down from 100 kilograms. His friend’s illiterate mother told not to touch her son in case he “caught AIDS.” Niyonsaba told her that the disease could not be passed on by touch, but to no avail.

“I hugged my friend tightly and kissed him on the cheek. He cried tears of joy,” says Niyonsaba.

Given only a few weeks to live, his friend had even begun making funeral preparations. However, when he began taking pills prescribed by a doctor referred by Niyonsaba, his health miraculously improved. Six months later, he was back to living a normal life.

Niyonsaba greets residents in Bungwe, Rwanda, in 2011. (Courtesy of François Niyonsaba.)

“You can’t completely cure HIV, but you can fight it with knowledge. Patients are able to lead normal lives. They can learn how to prevent illness and earn income. They can go to the hospital and buy medicine. There’s plenty we can accomplish by providing better education and tackling poverty,” says Niyonsaba.

First Ever Non-Japanese Dean

In April 2024, Niyonsaba became dean of Juntendō University’s faculty of International Liberal Arts, the first non-Japanese ever to be appointed to the position. It is believed that his fluency in five languages (English, French, Chinese, Rwandan, and Japanese) and his ability to foster cross-cultural understanding via his knowledge of health were behind his selection. The university’s stance of nondiscrimination on the grounds of nationality, gender, or educational background was also in his favor.

One of the aims of the faculty is to train medical interpreters, who work with doctors and nurses to help them provide healthcare services, and health promoters, who work to further knowledge on prevention of diseases.

Niyonsaba lectures students on fighting infectious diseases. (Courtesy of Juntendō University)

As dean, Niyonsaba particularly wants to concentrate on education on global infectious disease strategies that cross national borders. Take HIV, for example. Until recently Japan was the only industrialized country to report an increase in HIV infections. Syphilis is also on the rise.

“People in Japan tend to think of infectious disease as something that doesn’t affect their country, which is hygienic and affluent. They are in a way defenseless,” he says.

HIV and syphilis are often transmitted sexually, but Japan’s sex education syllabus provides little information, causing many youngsters to obtain incorrect information online.

“We need to teach students about their sexual health and make them realize that infectious disease is something that could affect them personally. It is too late to try and contain an infectious disease once it has spread. We learn for the future and for future generations. This is not an issue that only affects far-away Africa,” says Niyonsaba.

“Health issues affect people everywhere,” says Niyonsaba. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki.)

Remembering the Words of Mandela

Niyonsaba says he looks up to Nelson Mandela, who fought to end apartheid in South Africa. He always has a quote from Mandela in his mind:

“We can change the world and make it a better place. It is in your hands to make a difference.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: In his capacity as dean of the International Humanities faculty at Juntendō University, François Niyonsaba specializes in the global issues of infectious disease education. © Fujiwara Tomoyuki.)