Silk Road Murat: A Hidden Gem of Uyghur Cooking in Southern Saitama

Food and Drink- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Uyghur Oasis

Diners in Japan looking to savor the flavors of the historic Silk Road need look only as far as southern Saitama. Just a short car ride west from Kita Urawa Station, on National Highway 17, is Silk Road Murat, a quiet eatery serving up flavors and aromas of Uyghur cooking from the crossroads of Central and East Asia. Opened in 2006, the shop, whose name means “hope” in the Uyghur language, serves as a window into a fascinating and diverse culture.

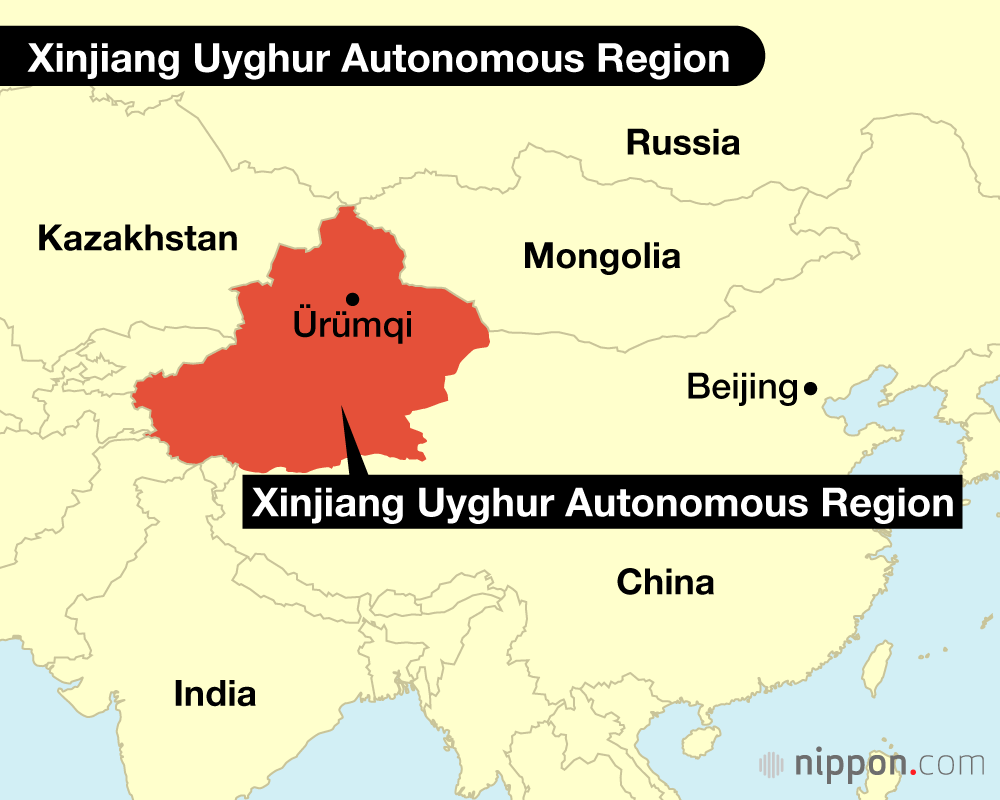

The Uyghurs are a primarily Muslim population from inner Asia, mainly living today in Xinjiang in northwestern China. According to a 2020 Chinese census, there were some 11.6 million Uyghurs living in the autonomous region, which borders countries like Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Mongolia.

The shop’s owners are a Uyghur couple, husband Eli Huxur and wife Aytursun Tohti. Since settling in Japan, the pair have dedicated themselves to sharing their native culture and foods with their adopted home. The interior of the restaurant reflects this, wrapping visitors in a distinctly Central Asian vibe, as does the menu, which features Uyghur dishes and other regional halal fare.

Eli arrives at Murat around 7:00 each the morning to start the day’s prep. When I poked my head in, he was hard at work making different varieties of Uyghur bread. A traditional food of wheat-rich Xinjian, this naan flatbread is the cornerstone of the Uyghur table.

Eli Huxur puts the finishing touches on Uyghur naan before baking. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

As Eli works the white, glutinous mass, its resemblance to freshly pounded rice cake making my mouth water. Eli carefully shapes the bread, adding toppings and designs as he goes along. He is helped by two male Uzbekistani employees, with the trio bantering in the Uyghur tongue. “We all speak similar Turkic languages, so communicating isn’t a problem,” Eli asserts warmly.

Soaking in the restaurant’s atmosphere, the close cultural ties of Uyghurs and other ethnic groups in Central Asia is evident. Take for instance the savory pilaf-like polo made with lamb, carrot, and spices, which is one of the shop’s most popular menu items. Renditions of the cuisine are also found next door in Uzbekistan, where it is known as plov and holds the status of national dish.

Another is the classic Uyghur breakfast, consisting of piping hot chai served alongside naan slathered with fig or apricot jam. Chai is common across the region from Turkey to India and beyond, but in a departure from varieties sweetened with sugar, as is the norm, the Uyghur version is flavored with a dash of salt.

A plate of polo, a dish found in various forms across Central Asia. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

Chasing a Dream

As I sit talking with Eli, a long-time Japanese friend of his pops his head in to say hello, and soon the two are affectionately chatting about the early years of their relationship. “I first met Eli when he came into the Japanese restaurant I was running at the time,” recounts the friend. “From there we started hanging out at a local izakaya. He was fresh off the boat and hardly spoke a word of the language.” Eli sheepishly acknowledges his early struggles with Japanese, asserting that he had enrolled in a language school in an attempt to learn. “You knew how to say kanpai, or ‘cheers,’ but not much else, right?” the friend jibes.

As is his style, Eli sees his visitor off with a gift of freshly baked naan and watermelon, a combination the friend insists is “delicious beyond description.”

Baking naan fills the restaurant with an enticing aroma. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

I am visiting on a Friday, a holy day in Islam, and Eli accompanies his staff to prayers at a nearby mosque. Returning to the shop, he describes for me his arrival in Japan in 1997 as a determined 27-year-old. “I wanted to become someone of note,” he declares, adding that his father had served as a regional governor and his older sister was a university professor. “I’d worked as an accountant at a state-run business, but having only graduated from technical college, I felt I needed to earn a bachelor’s or even master’s degree if I had any hope of raising my social status.” Following his sister, who happened to be studying in Japan, he arrived in the country bent on laying the groundwork necessary to become a member of the Uyghur elite once he returned home.

Living in Japan brought an endless supply of surprises. He was awed by the automatic ticket gates at train stations and vending machines on street corners, which made Japan seem leaps and bounds ahead technologically. Even the public toilets at parks were like nothing he had ever seen—the first one he encountered he mistook for a villa. “I was blown over by the Japanese propensity for detail.”

The way of life also presented startling differences to his own native culture. “There isn’t a reliance on kin bonds or payoffs to be successful,” he says. “Even children of wealthy families have to get by on their own merits.”

Eli eventually completed his language studies and was accepted to a Japanese university, where he studied economics. Upon graduating, he landed a job with an automotive parts maker that was looking to open a branch in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Zone. Soon after, though, the firm’s new business plan ran into problems, and Eli decided to leave. “The CEO didn’t want me to go,” he says. “But I didn’t see a future there.” His search for a new career path led him to the food industry. “I had worked at a family friend’s restaurant back home, so I had some experience. I was a good cook, to boot, so I set about opening my own shop.”

Heart of Uyghur Cuisine

The decision to obtain a chef’s license and open his own restaurant was the culmination of a gradual shift in Eli’s life trajectory, and one that I suspect is deeply intwined with the political situation in his homeland. I have repeatedly probed him on this point, but he has steadfastly remained tight lipped about his change of heart.

Pouring his efforts into his restaurant, Eli has carved out a niche for Silk Road Murat among local residents and overseas transplants alike. Despite its out-of-the-way location, the eatery draws a diverse flow of customers that includes Uyghur natives, Muslim exchange students, blue-collar workers, Japanese fans of ethnic cuisine, and people from the neighborhood. The clientele is predominantly local and Japanese, attesting to the appeal of Uyghur flavors.

Eli’s wife Aytursun says that savoring the wide array of ethnic cuisines available in Japan has helped foster for her a new appreciation for her native Uyghur cooking. “Spices factor large in the culinary cultures of many predominantly Muslim nations,” she explains. “Uyghur food is no exception, with its use of seasonings like cumin, pepper, and coriander. But the flavor overall is quite mild, which many Japanese customers find pleasantly surprising.”

Working at the restaurant and raising their two children in Japan, the husband-and-wife- team have entrenched themselves in the local community. Aytursun regularly attends neighborhood gatherings and has been active in sharing the food and customs of her native land.

Aytursun Tohti holds cooking events and other gatherings introducing Uyghur culture. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

One of her favorite Uyghur foods to introduce is laghman, a savory combination of hand-pulled noodles, fried lamb meat, and vegetables. Bringing me a bowl, Aytursun insists that the dish, with its soup flavored with garlic and ginger, fights fatigue. I tuck into the noodles, savoring the rich flavor of the ingredients, and in no time the warm broth and spices have me warm down to my toes.

Aytursun considers it the duty of Uyghurs like herself who are living abroad to be ambassadors for their homeland. “Many first-time customers ask if Uyghur is a type of cooking,” she declares with a hint of dismay. “I want to teach the world about who we are.”

Laghman is one of the best-known dishes of Uyghur cuisine. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

Eli has spent half of his life in Japan, building a business and raising a family here. “The shop has sustained us,” he reflects, “which is all I ever hoped for it to do.” He insists that he has no plans to pass the reins to his children. “I want them to see the world, and make the most of their own lives.”

He says that he is looking forward to relaxing in his old age, particularly relishing the idea of spending long hours soaking in hot spring baths. However, his homeland is never far from his thoughts. “I might decide to return someday,” he declares. “After all, no one can say what the future holds.”

The exterior of Silk Road Murat. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

Uyghur Cuisine: Silk Road Murat

- 3-20-13 Sakawa, Sakura Ward, Saitama, Saitama Prefecture

- Tel.: 048-852-3911

- Open 5:00 pm to 11:30 pm daily; open for lunch 11:30 am to 3:00 pm Saturdays and Sundays only

- Closed Mondays

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Eli Huxur, at left, and Aytursun Tohti outside their restaurant Silk Road Murat. © Kumazaki Takashi.)