Japanese Support for Educational Reform in Egypt

Education Global Exchange Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Introducing Tokkatsu to Egyptian Schools

Tokubetsu katsudō, or tokkatsu, are special activities outside the academic curriculum that can include class meetings, the designation of students as class leader of the day, classroom cleaning, sports days, and field trips. This feature of Japanese school life is often taken for granted as part of the elementary and junior high school curriculums intended to foster initiative and collaborative spirit.

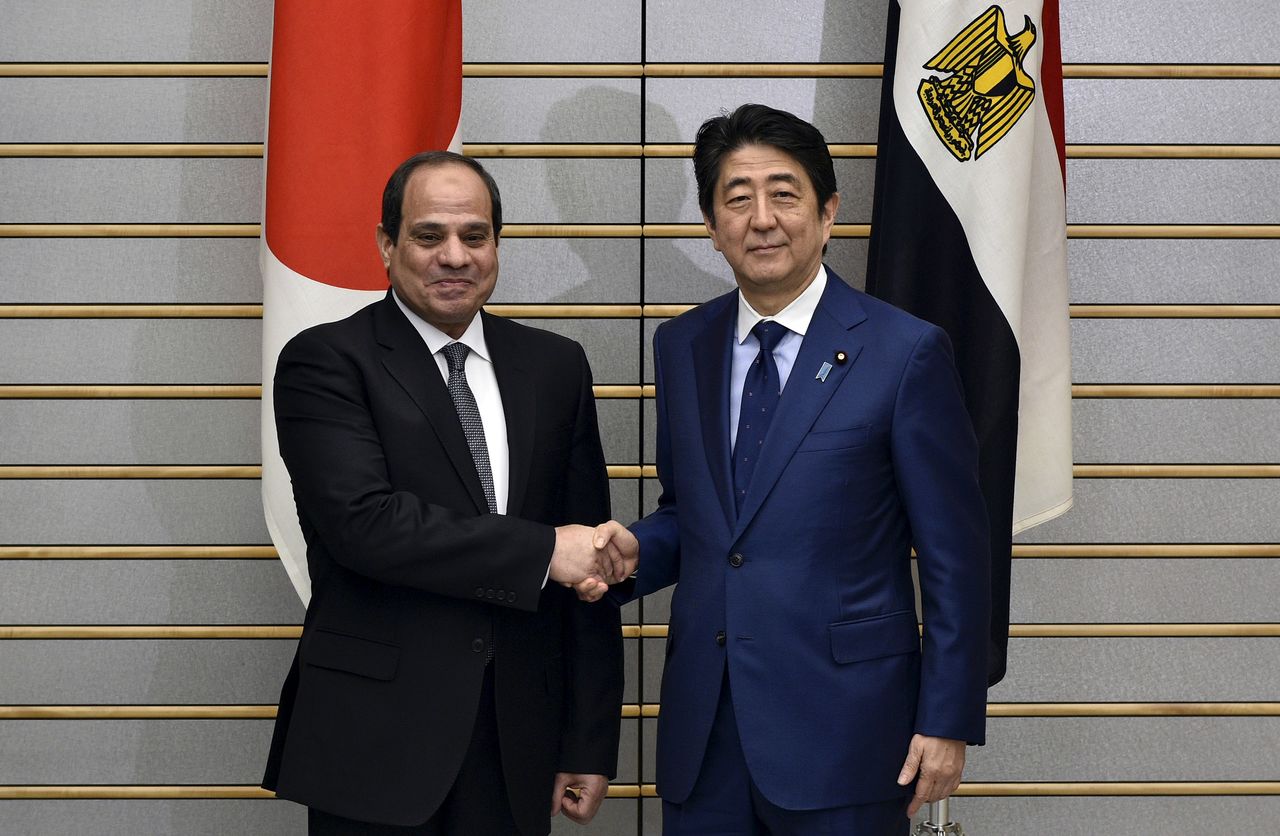

An increasing number of countries are incorporating tokkatsu into their school programs. One particularly enthusiastic adopter is Egypt, which entered into the Egypt-Japan Education Partnership on the occasion of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s visit to Japan in 2016.

Public elementary school classes in Egypt often average 55 students per class. Teaching is usually lecture-style, and students have few opportunities to express themselves. Public unrest and unemployment began to grow in the 2010s, leading to an urgent need for education focused on creating human resources with problem-solving skills. President el-Sisi, who took office in 2014, moved to revamp his country’s educational system, taking cues from Japanese education, which he believed had been key to Japan’s success in the postwar era thanks to its hard-working, rule-abiding citizenry.

A public school classroom in Giza, Egypt, in 2013. (© Reuters)

President el-Sisi and Prime Minister Abe Shinzō announce a joint partnership on education on February 29, 2016, in Tokyo. (© Reuters)

A number of tokkatsu features—class meetings, class leader of the day, and guidance for inculcating good personal habits—were introduced in over 18,000 Egyptian public schools beginning in September 2018. New public Egypt-Japan Schools were also established at the same time. Replacing the traditional classroom style of students packed onto benches and sharing long desks, classes were limited to 36 students provided with individual desks and chairs. This new education style attracted great public interest, with applicants far outnumbering the number of school places offered. Thirty-five such elementary schools opened in the program’s first year; today, their number has grown to 51.

Short-Stay Training Program for Egyptian Teachers

To support teachers under the EJEP, the University of Fukui’s United Professional Graduate School offers training to familiarize Egyptian teachers with Japanese education, in cooperation with the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Fukui is among the top-achieving prefectures in terms of students’ academic performance and physical fitness and offers classroom visits and training to educators from Japan and abroad.

Since 2019, groups of 40 teachers from Egypt have taken a four-week training course at the University of Fukui; the cumulative number of program participants is expected to reach 820 by 2026.

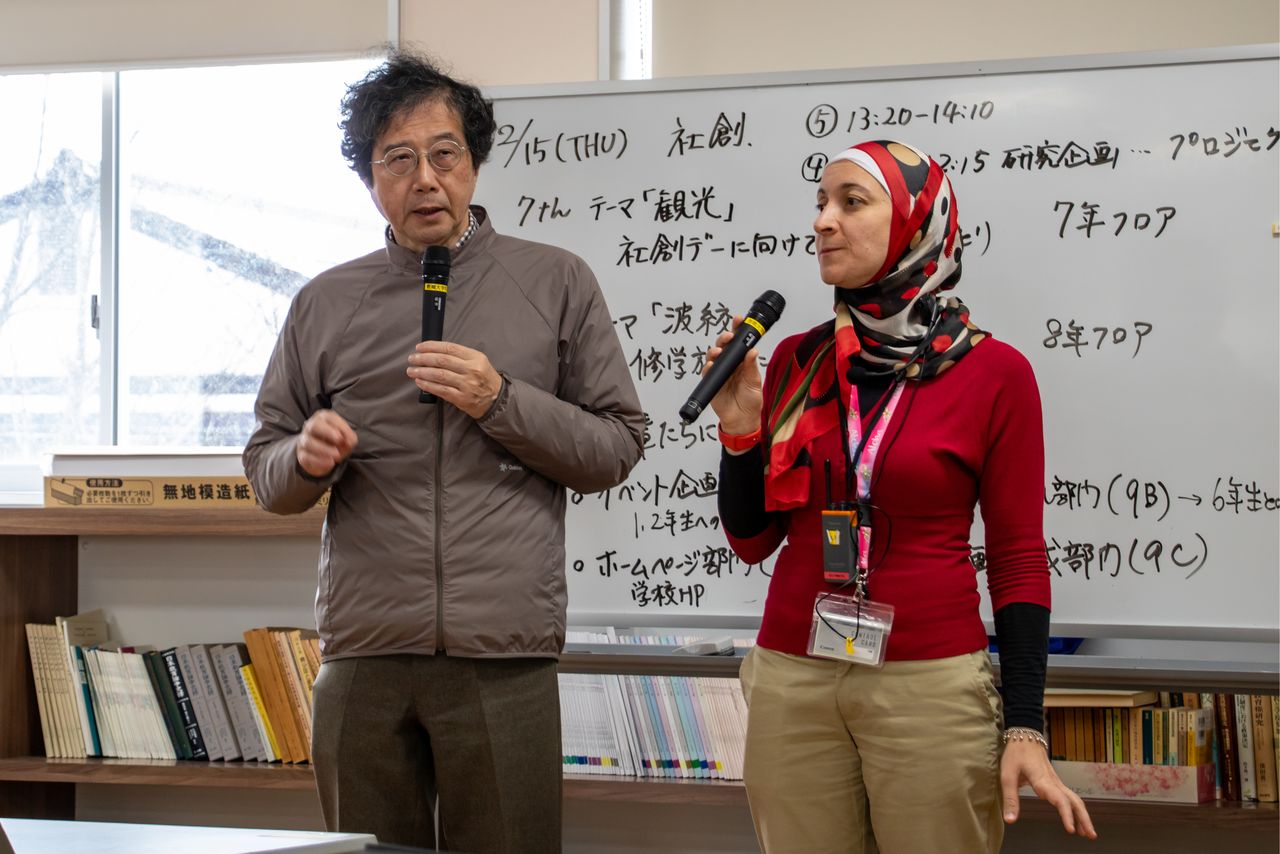

Yanagisawa Shōichi and Yasmine Mostafa, professor and assistant professor, respectively, at the University of Fukui, lead a training session. (© Nippon.com)

In February 2024, the tenth group so far, which included EJS principals and vice-principals, arrived in Japan. The group toured kindergartens, as well as elementary and junior high schools, mainly in the city of Fukui, and attended training sessions. On the day I reported, the teachers were observing a lesson at the junior high school attached to the University of Fukui’s School of Education. The students had paired off for group work to identify an issue of their own choosing and explore solutions.

The students’ group work targeted “what we want our juniors to know,” a theme they pursued throughout the school year. (© Nippon.com)

Group work is a new compulsory subject added to the senior high school curriculum in 2022. Teachers themselves have no experience teaching this subject, so hitting on the right teaching method is a trial-and-error process for them.

Although not schooled in the Japanese educational system themselves, EJS instructors also aim to teach in the Japanese education style. For this reason, says Professor Yanagisawa, they make use of the group work approach to shape their curriculum, holding discussions to share their day-to-day thoughts about the training program and issues they have experienced.

Yanagisawa notes: “Japanese-style education tends to emphasize tokkatsu, but if the Egyptian teachers are simply there to observe classroom lessons, they may feel it’s pointless because Japanese children are not the same as their Egyptian counterparts. The essence of this training program is to acquaint the teachers with the process of nurturing children’s initiative.”

At a group discussion session, EJS teachers applaud each time someone makes an observation. (© Nippon.com)

Reports from previous cohorts are valuable for helping program participants picture how to take advantage of the learning acquired from touring Japanese schools. To that end, the program connects current participants with previous participants online, to learn how their peers are implementing their knowledge in Egypt.

“The current group hear what previous cohorts learned and how those teachers are trying their best to implement that learning in their schools, so that they can profit from their training here. And at the end of the program, the current group are asked to write reports too. That accumulative process helps raise the level of receptivity for each subsequent cohort.”

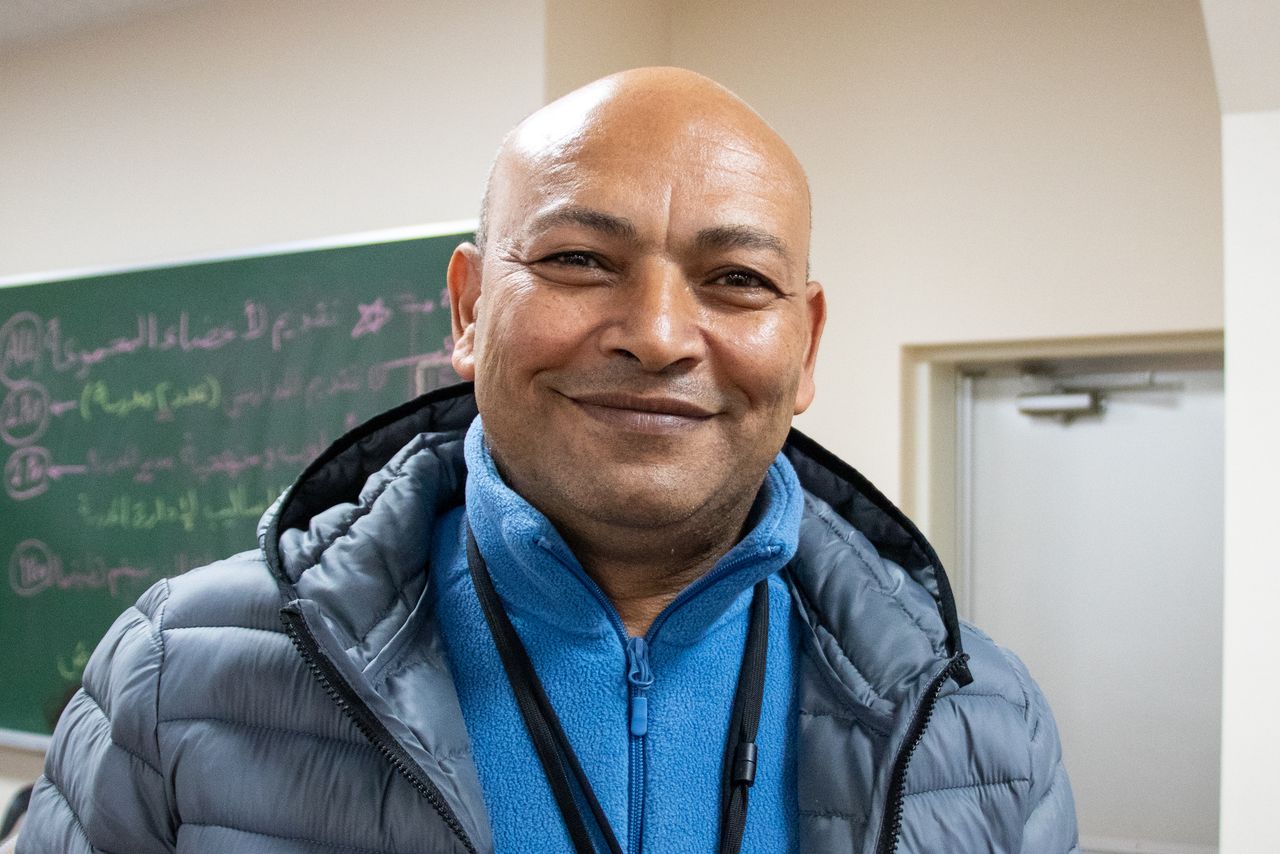

The principal of the EJS Port Said Elementary School says that actually seeing classroom cleaning and other activities made him realize that they help stimulate the children’s personal development. (© Nippon.com)

Teachers from Egypt observing a broad-ranging training session for Japanese teachers. (© Nippon.com)

A Model for Success?

Professor Yanagisawa and his University of Fukui colleagues visited Egypt in May and observed EJS activities to follow up on teachers who had previously attended training in Fukui. Assistant Professor Yasmine Mostafa, who was in Egypt observing classroom lessons and participating in local teacher study groups, believed that the program was yielding strong results.

“Previously in Egypt, it seemed to me there was a gulf between the school administration side, represented by the principal and vice principal on the one hand, and the educators on the other. But now, there is mutual trust and everyone is working together to create better schools. The changes in the teachers also have a beneficial effect on the children, as lessons now encourage them to actively participate.”

Overall, children at EJS enjoy taking part in school activities and preparing for events, and are so keen that they say they don’t want to go home, or wish they could come to school even on holidays.

A visit to an EJS class to follow up on the progress of a group of teachers recently in Fukui. (Courtesy University of Fukui United Professional Graduate School)

At the EJS junior high school level, the curriculum includes not only tokkatsu but also group work on study projects, where students do independent research and reach their own conclusions. Professor Yanagisawa notes that the growing number of EJS students will require stronger management skills on the part of teachers, but hopes that the new school culture now emerging will help with that and other issues.

Meanwhile, in Japan, activities outside the academic curriculum place a heavy burden on teachers, and, responding to criticism, schools are starting to scale back on such activities.

“In some respects, tokkatsu in Japan have become so matter of course that they’ve lost substance. Some voices also claim that tokkatsu are not necessary because there are no similar activities in American or European schools. But will children want to go to school where they are simply sitting and listening to lectures and competing with each other to get the best test scores? The training we offer has shown that the Japanese child-centered education model can serve as a model throughout the world. The education reforms Egypt is implementing can contribute to similar changes throughout the Arab world and Africa.”

There are also lessons for Japan in Egypt’s energetic embrace of education reform. One hopes the countries will work together to nurture an education culture they can be proud of.

When EJS first opened, parents disliked the idea that their children were expected to clean their classrooms. Today, there is better understanding of Japanese-style curriculum elements. (Courtesy University of Fukui United Professional Graduate School)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: An elementary school in Egypt where tokkatsu, such as classroom cleaning, has been adopted. Courtesy University of Fukui United Professional Graduate School.)