Keeping the Zainichi Memories Alive: Grandmothers’ Lives Etched in the Kawasaki Landscape

History Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Spring 2024 saw the release of Arirang Rhapsody: Halmeoni Beyond the Sea. Directed by Kim Sung-woon, the documentary film focuses on Zainichi Korean women living in the Sakuramoto district of Kawasaki, Kanagawa. An excellent example of “living postwar history,” the film details the turbulent lives of Korean women at the mercy of Japan’s colonial and wartime policy, as well as postwar events, through the stories of the women themselves. Tossed back and forth between their colonial homeland and Japan, Kim’s work shows the modest but ultimately happy lives they finally etched out for themselves in their later years.

Seo’s Story

Seo Yuseun was born in 1926, in South Gyeongsang Province, Korea. Seo came to Japan with her mother in 1940 at the age of 14, married, and gave birth at age of 18. Seo tells her wartime story to the camera: “Heavy labor in lathe factories, textile mills, and mines. We did it all. I worked with my family, and we all supported each other . . .”

When the war ended in 1945 with Japan’s defeat, the family acquired a small boat to return to the Korean Peninsula. Soon after, Seo’s mother and husband died, and she and her 3-year-old daughter were caught up in brutality of the Korean War that broke out in 1950. With her family torn apart and separated in her homeland, and with the prospect of further fighting always on the horizon, Seo made the decision in 1957 to return to Japan, leaving her young daughter in the care of relatives.

Japan’s border was closed, but by hiding in fishing boats continuously buffeted by the waves and overflowing with water, she was determined and even “prepared to die” to cross back into Japan. Until her retirement in 2004 at the age of 78, Seo Yuseun never stopped, frantically performing hard labor at construction sites, cleaning buildings, and washing dishes.

At one point on camera, Seo wipes away tears with a handkerchief, lamenting that “Nothing good came of my life.”

The Colonial Distortion of Korean Lives

The tumultuous and often painful lives of these halmeoni (Korean for grandmother) in Arirang Rhapsody confront the viewer with the stark reality that Japan’s colonial policy and war greatly distorted the fate of the people of the Korean Peninsula. With Japan bringing Korea under formal colonial rule in 1910, Koreans’ lives were disrupted, and many were pressed to leave their homes and places of work and come to Japan. Furthermore, with Japan’s invasion of China in 1937 and the effective beginning of World War II in Asia, Koreans were conscripted to work in mineral and coal mines in Japan until the end of the war in 1945. In that time, a total of about 2 million Koreans crossed the Sea of Japan.

An estimated 600,000 remained in Japan after the war. Many Koreans settled in the southern part of Kawasaki, where they built their own community. Despite facing discrimination and cultural and language barriers, they provided each other with support.

Director Kim Sung-woon himself is a second-generation Zainichi, or Korean resident of Japan. He had already turned his camera on the first generation of Korean women living in Kawasaki’s Sakuramoto district in the 2004 Hana hanme, his debut documentary. However, he did not really capture just how turbulent their lives were in this first installment.

What motivated Kim to reengage with the topic in the way he did? In essence, he wanted to preserve the memories and perspectives of the last generation of people who directly experienced the war and can speak about it from the Zainichi perspective.

“As the halmeoni who could tell us directly about our history began to pass away one after another, I felt a tremendous sense of crisis. The experiences of the first generation of Koreans in Japan are not only individual histories but are also the history of the region and of Japan itself. I wanted to record their words while there was still time.”

Connecting with Halmeoni and Japan’s History

Many others shared Kim’s sense of crisis. As such, Arirang Rhapsody was far from an individual effort. For example, others have created “study tours” around the Kawasaki waterfront area where people could listen to explanations of the town’s history as it relates to the Zainichi community.

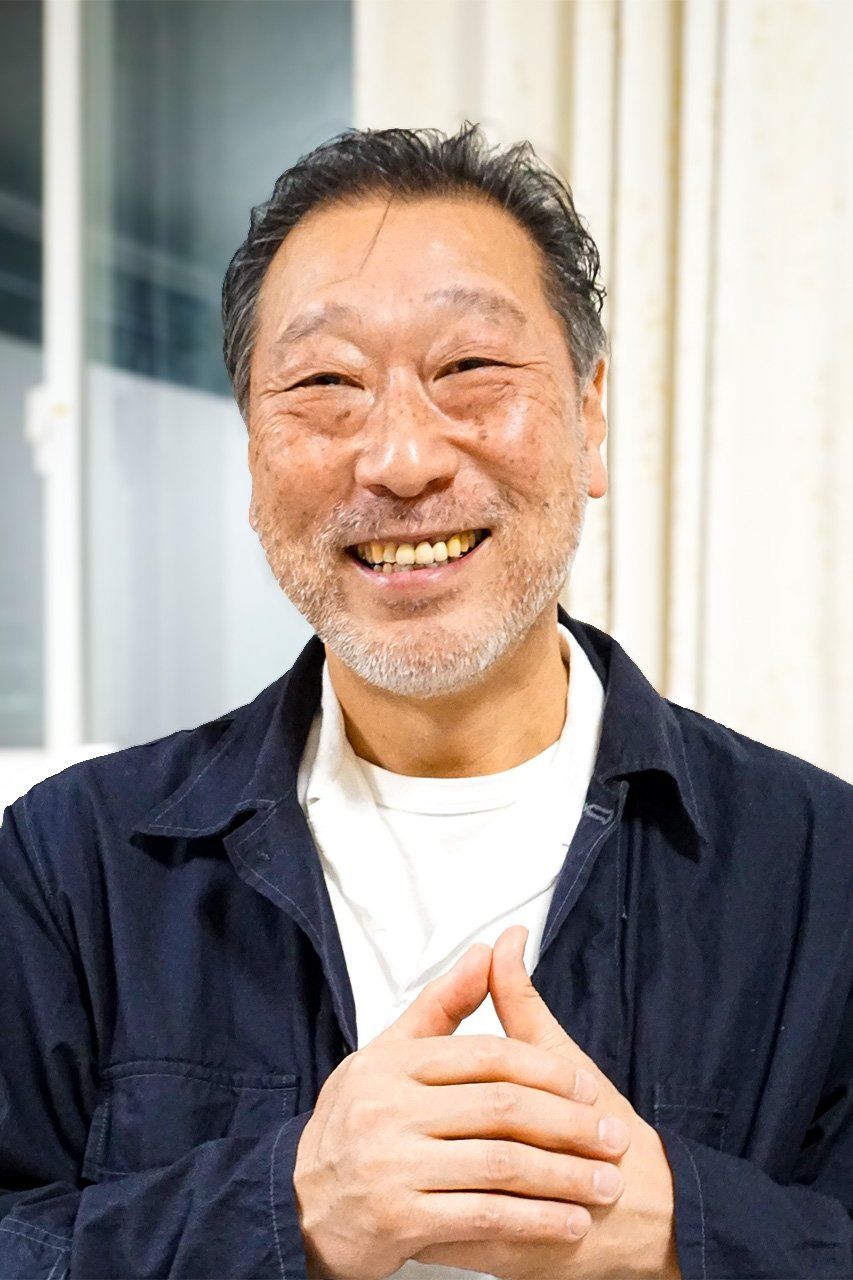

One of the organizers, Miura Tomohito, explains:

“The first generation of Korean immigrants to Japan were truly strong-willed people. They never gave up fighting against unreasonable discrimination. The history of their lives is deeply imprinted on this town. By thinking about the lives of these women, I want people to be able to share in the memories of this area and how it came to be today.”

Miura Tomohito, President of Seikyū-sha, a social welfare organization for Zainichi children that operates a nursery school, kindergarten, and friendship hall in Kawasaki. (© Hamada Nami)

I accompanied Miura as he led a group of volunteers on one of these study tours.

Miura (right) and tour participants in Kawasaki. (© Hamada Nami)

Miura was particularly enthusiastic when he discussed the Kawasaki Friendship Hall. In 1988, the city government established this public facility to promote multicultural coexistence and promote reflection on the history of discrimination against the Korean residents of Japan. It has various functions, including as a children’s center and community center, but the officially registered social welfare organization chaired by Miura also offers Japanese literacy classes based on “joint learning.”

Why were literacy classes even necessary? The completion of Friendship Hall coincided with the retirement of the first generation of Zainichi women who had worked tirelessly throughout their lives. These halmeoni were invited to these classes because many of them had reached old age without ever learning to read or write.

As Miura recalls, “The halmeoni didn’t know how to hold a pencil or how to apply the right amount of pressure when writing. But it was moving to see them learning to write with such enthusiasm.”

At the same time, he noticed the halmeoni began to ask themselves: “Why now, at this age, am I only beginning to learn to write?” As they began to discuss this, they spontaneously began to talk about their own extraordinary lives as they entered a new stage.

Miura further shares that, “by working hard and building Zainichi communities throughout Japan, halmeoni made their own place in Japanese society. They were, however, too busy surviving the war, working for a living, and enduring discrimination to have time to learn how to write.”

Second-Generation Zainichi Achievements

It was a public scandal revolving around discrimination that originally brought Miura to the Kawasaki area half a century ago.

The “Hitachi discrimination scandal” started when Pak Chon-sok, a second-generation Zainichi high school graduate from Aichi Prefecture, passed the Hitachi employment exam using a Japanese alias. He was later rejected by Hitachi after revealing that he was a Zainichi Korean. Pak did not accept this outcome, though, and sued Hitachi in 1970, eventually winning the case in 1974.

Miura was active in Japan’s burgeoning student movement of those years, and many lent their support to him, helping to accelerate the elimination of legal discrimination against Zainichi in Japan. Miura says: “We Japanese who were involved in the history of this case want to pass on the spirit of it to younger generations.”

Yamada Takao is the founder of the study tour initiative and a former Kawasaki city employee. The Hitachi incident also had a life-changing impact on Yamada.

Former Kawasaki official Yamada Takao in front of Kawasaki Station. (© Hamada Nami)

Pak, dejected and about to return to his hometown after his dream of finding employment was shattered, met Yamada, who was also active in the student movements of the time. Yamada also decided to offer his support to Pak. To do this, he became a Kawasaki City employee and, by chance, was assigned to a branch office supervising the Sakuramoto district. He became a so-called alien registration officer in charge of monitoring the area’s foreign resident population.

In 1974, a second-generation Zainichi man attending a community meeting regarding Pak’s trial stood up and shouted: “It’s not just private companies that are discriminating. Why can’t we access municipal housing even though we pay the same taxes as Japanese? Why can’t we get the same child allowances as others to raise our kids?”

Encouraged by the victory in the Hitachi case, second-generation Zainichi accelerated their activism to eliminate discrimination. The following year, the Kawasaki government abolished the nationality clause for municipal housing and created a special budget for funding child allowances. This was the beginning of a movement toward “multicultural coexistence” in Kawasaki and Japanese society.

“Humans Are Strong”

Arirang Rhapsody shows the halmeoni succeeding in their efforts to learn to write and draw for the first time in their lives. They express their thoughts in writing and visually, and the film often shows them smiling like children.

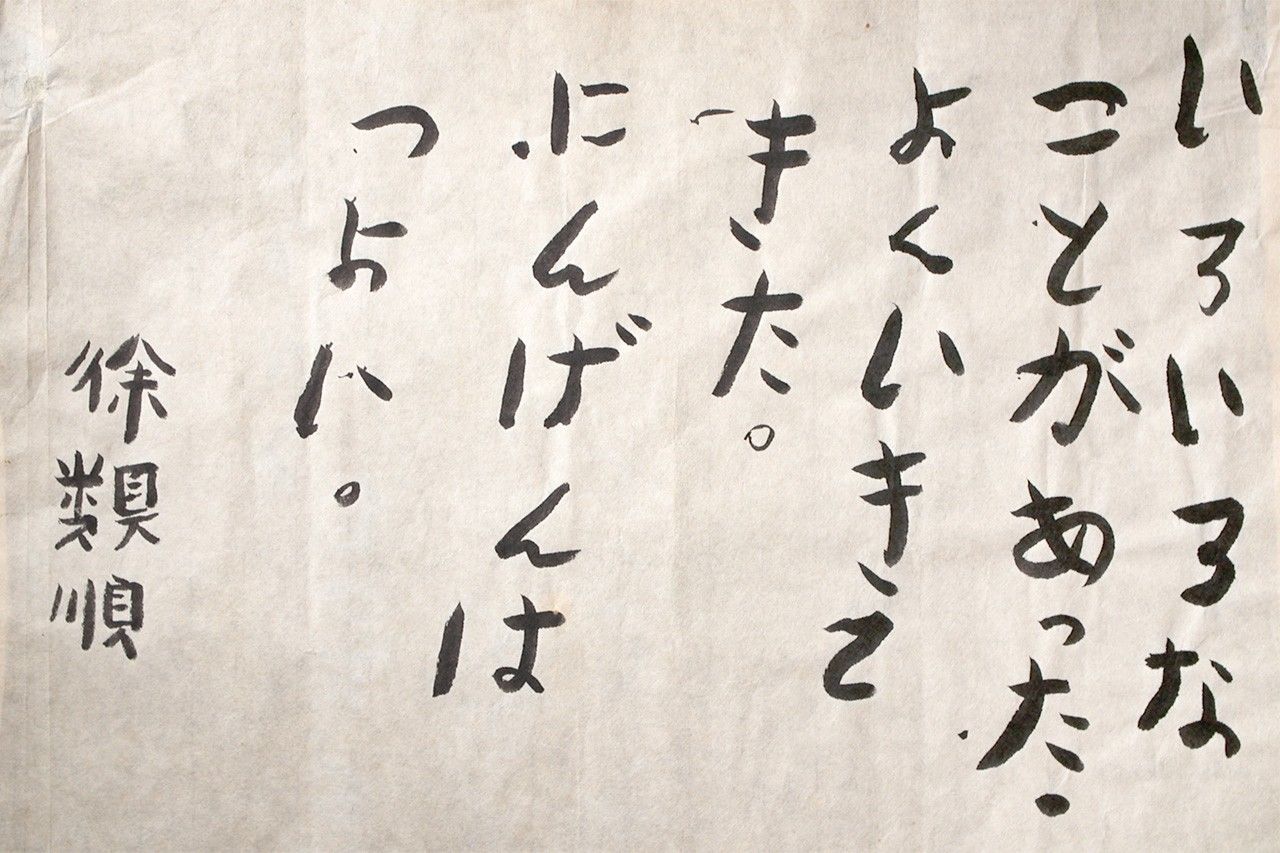

The camera then shows one of the essays filling the entire screen. It says:

Many things happened. But I have lived a long and good life. Humans are strong.

Seo’s writing after she participated in “joint learning” at the Kawasaki Friendship Hall. (© Kimoon Film)

These were the words of Seo Yuseun, who had previously wept on camera saying, “nothing good has come of my life.” The text is written in almost child-like hiragana, but the text and its sentiment represent a powerful expression of self-praise.

In 2024, Seo will be 98 years old. She is living a peaceful life with a smile, watched over by people like Miura who are always behind her.

(Originally published in Japanese. Research and interviews by Power News. Banner photo: Zainichi halmeoni showing off the results of their “joint learning” at the Kawasaki Friendship Hall. On the right is Seo Yuseun. © Kimoon Film.)

World War II Kawasaki Korea history war Korean Kim Sung-woon halmeoni