Manga as a Window on Japanese Culture

“Shima Kōsaku”: A Salaryman Manga and the Evolution of Japan’s Economy

Society Manga Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Pioneering Manga

From the postwar decades through the late twentieth century, Japan’s burgeoning economic power attracted global attention. After the nation became the world’s number two economy in the 1970s, American sociologist Ezra Vogel wrote a book entitled Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (1979), situating Japan’s success in a communitarian culture where businesses treated employees as family, there was a collective drive to learn and improve, and exam-based education was meritocratic.

Japanese business, of course, was not unreservedly praised. People derided the Japanese commercial model as one pursued by an “economic animal” that only churned out imitations of Western products, thought solely about money and profit, did not respect worker individuality, and expected these workers to sacrifice completely for their organization. Foreigners satirically labelled Japan’s businesses using the moniker “Japan, Inc.,” and it was not unusual at the time for people to joke that Japan was the world’s “most successful socialist nation” (a term, amusingly enough, later applied to the People’s Republic of China instead).

Fundamental to the image and reality of “Japan, Inc.” was the “salaryman,” the permanent, full-time worker who dedicated his life to the company. The salaryman still exists today, of course. However, there are some nuanced differences between the image of the contemporary salaryman and the one who made the morning commute when Vogel wrote his book.

For example, the practice of long-term employment was common, and a seniority-based personnel system that ensured slow but upward mobility was still in place. If you studied hard, graduated from a good school, and got a permanent position at a good company, it was assumed that you were set for life. The company guaranteed stability for you and your family, although these salaried workers were expected to prioritize their work over other aspects of their lives.

Even then, the salaryman was not universally admired. These men were seen as figures of elite pride who endured a sad existence. Dressed in impersonal gray suits, they would ride the train to work every day. They had little time to reflect on their personal lives and were often neglected by their families, who saw them as external to the household’s activities. Seeing their parents sacrifice like this, a new generation began to reject this as their destiny as if to say, “I don’t want to be an ordinary salaryman!” They sought freedom rather than stability.

Yet this humble existence was the source of inspiration for a new type of storytelling in Japan. While there were few exciting or dangerous plotlines, Hirokane Kenshi’s Shima Kōsaku pioneered the salaryman manga genre.

On the Eve of the Bubble Economy

Shima Kōsaku: Section Chief began its serialization in Kodansha’s Morning magazine in 1983. The following year, the Nikkei topped 10,000 for the first time, and the 1985 Plaza Accord, which sought to redress the trade balance between Japan and the United States, was just around the corner. This was the eve of the financial madness of the bubble economy that took place in the second half of Japan’s 1980s.

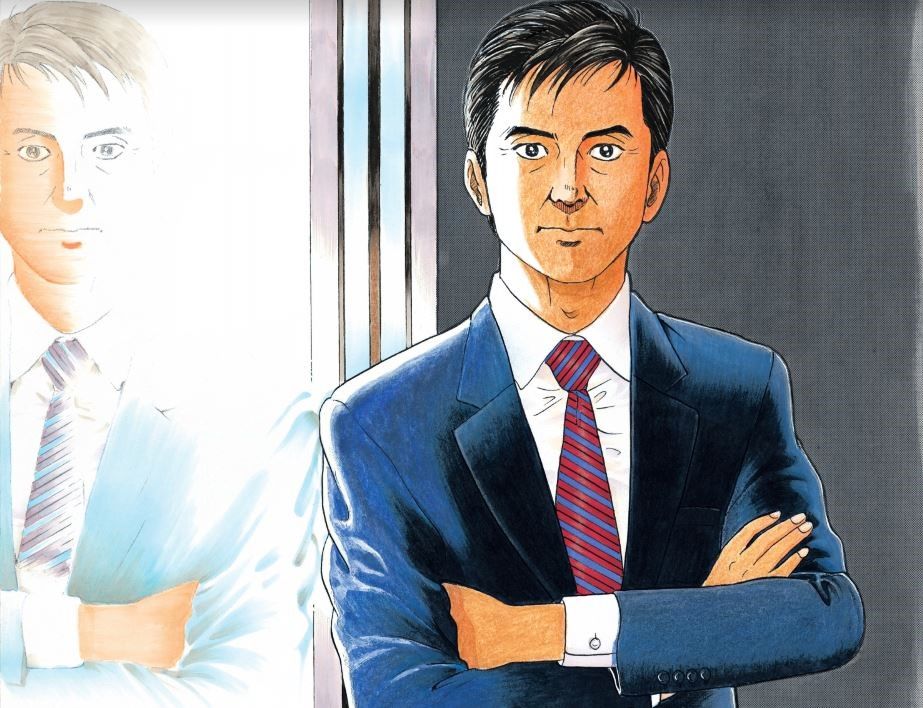

The manga’s protagonist is Shima Kōsaku, a salaryman at the fictional Hatsushiba Electric conglomerate (loosely based on Matsushita Corporation, later Panasonic, where the author once worked). Shima is married, but his wife shows no interest in his work. He also has one daughter. In the first installment, Shima is introduced while he is still assistant manager but has just been informally tagged for promotion to section chief. The story depicts Shima’s travails as he is caught up in an affair with a female subordinate, potentially jeopardizing his promotion. Throughout the course of the series, Shima becomes division chief, then an executive, and eventually rises to the top of his company. Shima is a life-sized characterization of the ordinary salaryman, together with a touch of pathos.

Many Japanese identified with Shima’s way of life. Shima is currently an independent director. (© Hirokane Kenshi/Kodansha)

Shima was born in 1947 and is part of Japan’s first baby boom generation, born in 1947–49. As in the rest of the world, the “boomer” generation has a particular reputation in Japan. For better or worse, this generation is viewed as strong, gruff, and ambitious. The social climate of the time was chauvinistic, and various forms of power and sexual harassment were common in Japan’s workplaces. While the government tried to address this by passing the Equal Employment Opportunity Act in 1985, Japan’s working environment did not immediately change in response.

Shima, however, was not typical of his generation. He had liberal values and a sense of justice which saw him stand up to discrimination even as a child. Although on the surface a mild-mannered person, when push came to shove, he displayed great courage, including standing up against underworld forces. He was not type of the person to engage in power or sexual harassment toward his subordinates.

He was also depicted as very popular with women in the manga, although was often in their shadow. For example, after becoming an executive, he was photographed kissing an actress, which became fodder for Japan’s weekly magazines. As he was divorced and single at the time, though, he had not broken any regulations or social rules, and it did not impact his position in the company. Shima was also greatly advantaged by his connections with women in the course of doing business.

This is why Shima emerged as an ideal archetype for a new type of Japanese businessperson on the eve of the bubble economy. The bubble would soon burst, and Japan would enter its economic “lost decades.” Taken-for-granted norms such as lifetime employment and the seniority system were about to fall by the wayside.

Thus, during his time spent in middle management, Shima viewed the company not as the source of his identity but as a place for “self-realization”. Any aspirations he had did not require him to sacrifice his values just to get ahead. And when he eventually did get ahead, he would dismiss this as “just good luck.”

The manga does indeed portray Shima as benefiting from tremendous good fortune, despite “being born on third base” and already enjoying considerable advantages. His success goes beyond that, however. Japan had entered an era where the past examples of success were no longer valid and new business approaches were required. Shima is now sought out as someone who can combine humanity with a global perspective, whereas before someone of his character would have been dismissed as “smart, but naïve and unable to be ruthless.” Shima therefore succeeds not only in business in Japan, but in China and India. He eventually becomes the head of a major corporation. The result is a unique and positive portrayal of a salaryman changing with the times.

A positive portrayal of a Japanese salaryman, Shima’s image has been used in various collaborations and commercial tie-ups. The images above show Shima holding canned coffee in the fortieth anniversary edition of the manga anthology Morning. (© Hirokane Kenshi/Kodansha)

Shima Kōsaku Leads the Way

There is plenty of intrigue that can serve as fodder for dramatic stories about the Japanese salaryman: relentless factional warfare, aggressive takeovers and ruthless bargaining by foreign companies, confrontation with underworld forces, encounters between lovers. Shima Kōsaku thus inspired new takes on the life of a salaryman, creating a new genre in the process.

For example, there is General Affairs Division Yamaguchi Roppeita (written by Hayashi Norio and illustrated by Takai Ken’ichirō). This was first serialized in 1985 in Big Comic and has long been considered an anthem for Japanese businessmen with its strong sense of pathos.

While Shima and Yamaguchi were already mid-level employees when they first appeared in their respective series, Arai Hideki’s From Miyamoto to You (1990) depicts an entry-level salaryman who grows into his role despite his painful clumsiness in both work and personal life.

As the bubble economy collapsed in the early 1990s, and Japanese society began to consider “structural reform,” a new superstar of the salaryman manga would arise. Salary Man Kintarō, written by Motomiya Hiroshi and serialized in Shūeisha’s Weekly Young Jump from 1994, follows the protagonist, Yajima Kintarō. What makes Kintarō interesting is that he became a salaryman after leaving behind a life where he was a leader of a motorcycle gang. Fortunate enough to get a job at a large construction company, his first job was as a pencil sharpener. He soon works his way up the company by joining forces with his colleagues and making use of personal connections that transcend the boundaries of the company. Kintarō is dynamic and surprisingly successful, eventually working for a foreign bank.

More manga works emerged in the 1990s, such as Yumeno Kazuko’s Kono hito ni kakero (Hiromi, a Long Tall Lady) based on an original story by Shū Ryōka. It features a career-track female employee at a megabank. All the while, Shima’s own career continued to progress during the 1990s. He would become a division chief, director, managing director, senior managing director, and eventually president and chairman of his organization. This was against the background of a Japanese society and business world still in turmoil.

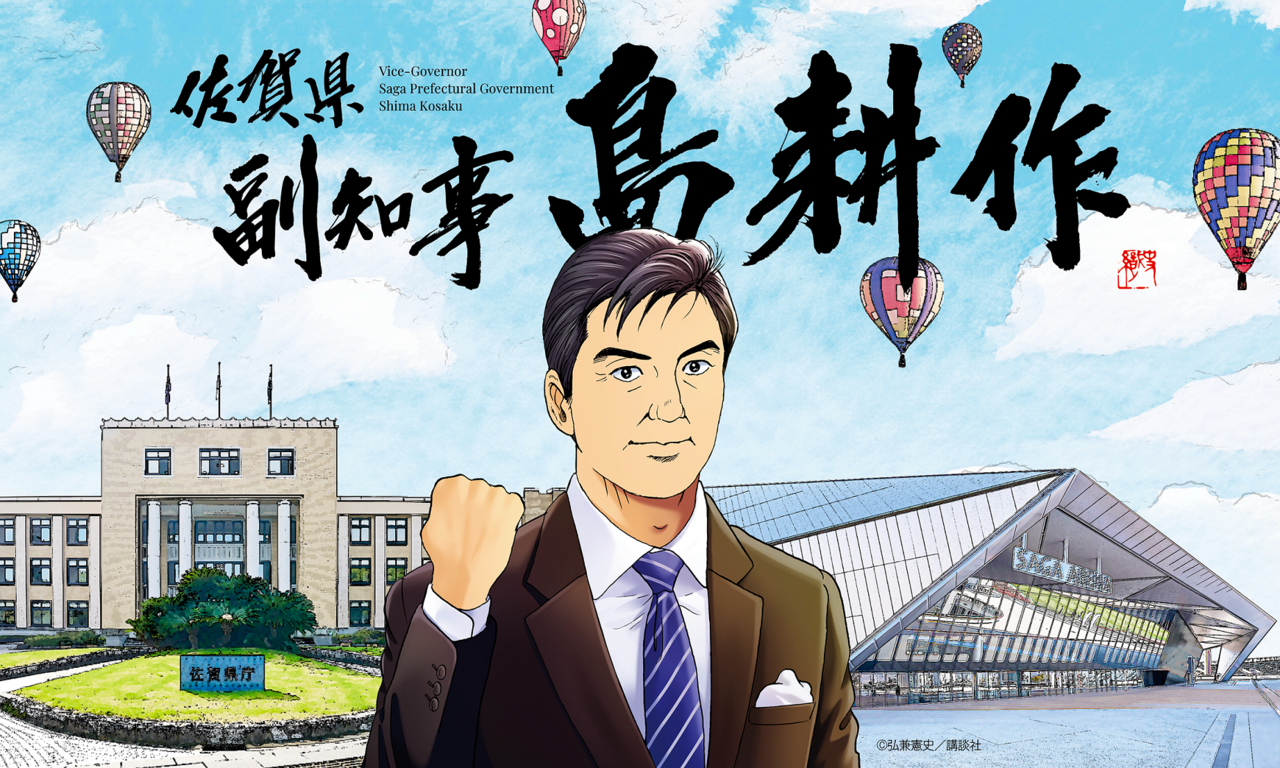

While he rejected an invitation to get into politics in the manga serialization, Shima in 2023 was appointed an honorary deputy governor of Saga Prefecture. This was a collaboration with the prefectural government as part of a project to promote Saga Prefecture based on various creative projects called “Saga-prise!” (a play on “surprise!”). (© Hirokane Kenshi/Kodansha)

Entering the twenty-first century, neoliberal policies focused on small government and labor reforms came to the fore. While Japan’s working population became more mobile, social disparities began to widen. At the same time, the “salaryman,” as a symbol of stability, lost its allure. Instead, in its place are depictions of “black” companies that exploit workers. One example is Mr. Tonegawa: Middle Management Blues (by Hagiwara Tensei, illustrated by Hashimoto Tomohiro, Miyoshi Tomoki), a spin-off from Fukumoto Nobuyuki’s Kaiji series. Serialized in Kodansha’s Monthly Young Magazine, it follows the story of Tonegawa Yukio and his agonizing struggle to keep his company’s evil chairman preoccupied and out of company affairs.

As discussions about “work style reform” deepen in Japan, and companies face demands from younger workers to consider new ways of working, what people look for in their employers has changed. Workers may now be more concerned with the ease of taking vacations and flexibility in working hours than with monetary compensation.

The image of businesspeople in manga has also changed. Rather than being part of a collective, they are more likely to be “self-made.” Trillion Game (by Inagaki Riichirō, illustrated by Ikegami Ryōichi) features the protagonist Haru, the self-proclaimed “world’s most selfish man,” who along with his engineering genius friend, Gaku, wants to earn a trillion dollars. In the manga Haru turns down a job at a major banking corporation when they do not hire Gaku, and instead the two set off to create their own business. Stand Up Start (written and illustrated by Fukuda Shū) tells the story of a protagonist who considers himself a “human investor” and, in an effort to reverse Japan’s image as a country lacking entrepreneurialism, decides to invest in people who might otherwise not get a chance in the current system.

These new manga follow characters who try to create their own career paths that suit their own ambitions and values. They also reflect changes in Japan’s own economy and society. This is also true for the appearance of more business manga targeted at women, such as Munō no taka (The Incompetent Hawk, by Hanzaki Asami), serialized in Kodansha’s women’s magazine KISS.

These are major changes from the time that Shima Kōsaku first made its appearance. Shima himself continues to evolve too—today he is an “independent director” who is playing an active role in the Japanese economy. We should therefore expect to see Japan’s “salaryman” manga become increasingly dynamic and more diverse from now on in line with changes in the Japanese business world.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The Shima Kōsaku series began in 1983 with Shima Kōsaku: Section Chief, at top left. The series has changed its subtitle at each step as Shima rose through the ranks—from section chief to division manager, director, president, chairman, and now, independent director. The instalment Shima Kōsaku: Student, at bottom, looks at Shima’s life before the original work. In total, the manga has sold over 47 million copies. Photo © Nippon.com.)

manga bubble salary baby boomers bubble economy Manga and Anime in Japan salaryman