A Pair of Authors Explore the World of Japan’s Traditional Tea Rooms

Books Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Uniqueness of Japan’s Tiny Tea Rooms

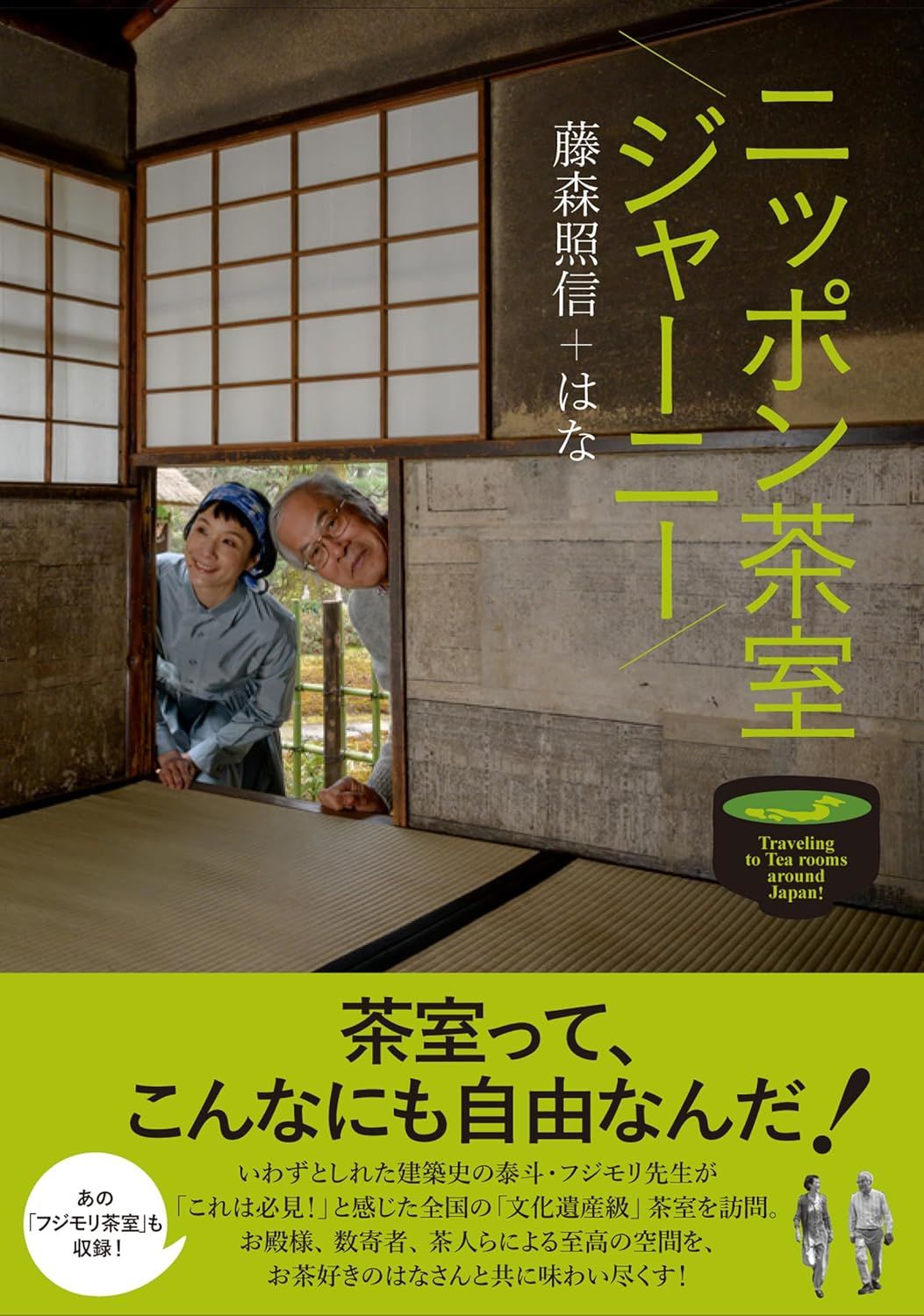

Author Fujimori Terunobu, professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, was born in Nagano Prefecture in 1946. He is an authority on world architectural history, also known for his own unique architectural designs. Fujimori is well-versed in sadō (tea ceremony), and his previous works include Fujimori Terunobu no chashitsu-gaku (Fujimori Terunobu’s Study of Tea Rooms).

His co-author, the fashion model Hana, attended international preschools and schools in Yokohama from the age of 2, and has been modeling since she was 17. She began practicing sadō in 2016, and has written books including Kyō mo okeiko biyori (Today is Another Good Day for Practice). She studied art history at Tokyo’s Sophia University, and is has been named a PR ambassador for Japan’s national treasures.

The pair combined their knowledge to visit 21 tea rooms in nine prefectures over the period of a year and a half. This book, formatted as a dialog, is compiled from a series of articles published in the monthly journal Nagomi from May 2022 to December 2023. It includes many color photos of tea rooms not open to the public, giving the reader a sense of actually visiting themselves.

In the introduction, Fujimori writes: “Wherever one looks around the world, specific buildings created for drinking tea only exist in the form of the Japanese chashitsu.”

Japan’s saint of tea, Sen no Rikyū (1522–91), created buildings specifically to invite guests and serve matcha tea to them. He based his designs on thatched roof huts used by hermits as retreats, generally a tiny 4.5 tatami mats in area (roughly 7 to 8 square meters), which Rikyū reduced in size even further.

Taian, a tiny 2-mat room created by Rikyū, still stands in the town of Ōyamazaki, Kyoto Prefecture. A national treasure, it is the oldest extant tea room by Rikyū, encapsulating his ideals. It is said he built it only for his sworn friend (at the time), samurai and daimyō Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98). Rikyū’s style of tea was tied to Zen Buddhism, and the tea room was therefore an enclosed space designed for introspection.

Joan: Tea Room of Oda Nobunaga’s Brother

The authors’ first stop is Urakuen, a traditional garden in Inuyama City, Aichi Prefecture, location of the tea room Joan, designated a national treasure. It was built by Rikyū’s leading disciple, Oda Nagamasu, also known as Urakusai (1547–1621), who was born in the Owari domain (in modern Aichi Prefecture).

According to Fujimori, although Urakusai was the younger brother of warlord Oda Nobunaga, he was “not a terribly good fighter, and preferred the world of tea and the arts.” Joan has numerous contrivances, including the window design: Hana describes the room as “brimming with Urakusai’s eccentricity.”

It was originally built in Shōden-in, at the temple Kennin-ji, in Kyoto’s Higashiyama district, as an escape from the world. Wealthy merchants the Mitsui family purchased the tea room in the Meiji era (1868–1912), and it was relocated to Urakuen in 1972. Curiously, the name Joan comes from Urakusai’s Christian baptismal name John.

A Tea Room with a Bath

In 1591, Rikyū was ordered to commit seppuku as punishment by Hideyoshi. Tea rooms built by Hideyoshi at his castle in Fushimi: Shiguretei and Karakasatei are now located in the temple Kōdaiji, in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto. Nejikago-no-Seki is a thatched-hut-style tea room constructed as a villa for the Owari domain’s chief retainer. It was moved to the Shōwa Museum of Art in Nagoya (where, sadly, it is not usually on display to the public). Kokyū-an, in Kyōtanabe, Kyoto, was the final residence of Muromachi period (1333–1568) Zen priest Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481).

Kōdaiji’s Shiguretei. (© Pixta)

Each of the tea rooms featured in the book has its own interesting story. Shōkadō Shōjō, a monk at the Iwashizumi Hachimangū temple in the early Edo period, built the tea room Shōkadō, located in Hachiman, Kyoto, after his retirement. The book describes how, in 1933, the founder of ryōtei (luxurious traditional restaurant) Kitchō joined a tea party here and was so moved by the four-compartment lunch box served that he created the famed Shōkadō-bentō boxed meal now served at his establishment.

The pair even visit a tea room with a bath! Kanden’an, a tea room in Matsue, Shimane, was built by local daimyō Matsudaira Harusato (1751–1818), nicknamed Fumaikō, for the Arizawa family, his chief retainers. It had an adjoining steam bath, where water was poured onto heated stones.

Another tea room in Matsue, Shimane, the Meimeian, was also built by Matsudaira Harusato. (© Pixta)

Free-Thinking Tea Room Design

The pair end their travels in Chino, Nagano, Fujimori’s hometown, where he has built a unique group of four tea rooms. Goan is a small, 4.5 tatami mat room reached by a ladder, while another tea room, Sora Tobu Dorobune (flying mud ship), is suspended by wires 3.5 meters above the ground. They could be considered twenty-first-century tea rooms, products of Fujimori’s rich imagination.

Tea rooms were not always tiny “2-mat” affairs. Despite being Rikyū’s disciple, Urakusai departed from his master in his belief that such rooms were too cramped for guests. This book also includes a selection of larger rooms.

At the conclusion of this tea room “pilgrimage,” Hana reflects on their discoveries: Will tea rooms evolve beyond Sen no Rikyū’s minuscule Taian, constructed to focus the guests’ attention on the bowls of tea served to them? Or will they return to Rikyū’s ideal in the future? Her journey together with Fujimori was a significant learning experience for better understanding sadō.

Hearths Rooted in a Distant Past

Fujimori believes that fire is the crux of a tea room. The tea rooms of Rikyū always contained a hearth for lighting a charcoal fire to boil water. He has a unique interpretation of the history of Japanese houses and their relationship to tea rooms.

Similarly to dugout pit dwellings of the Jōmon period (ca. 10,000–300 BC), Japanese minka homes always had a fireplace in the center where people cooked and gathered to relax. In the following Yayoi period (ca. 300 BC–300 AD), when raised-floor-style housing was developed, and in later Heian-period (794–1185) palatial architecture and the shoin-zukuri style used for military and temple residences, the fire was moved to a separate, lower area, the dirt-floor doma, and was handled by servants. Even in the world of tea, servants originally prepared the tea in a separate room to serve for their master’s guests.

Rikyū upended tradition by handling the fire and preparing the tea himself. In this regard, hearths used in tea rooms can be considered as a return of sorts to the more ancient Jōmon pit dwellings.

Rikyū caused a cultural revolution in the tiny space of the tea room: He is credited with perfecting wabi-cha, a style of tea that emphasizes simplicity and a rarified spirituality. But the hidden rooms used for tea were likely also used to conduct confidential discussions touching on the dirty details of political intrigue, too. Although tea rooms were mainly visited by men in the past, now women commonly frequent them. In this book, Hana opens the door to this free-spirited nature of tea rooms.

Nippon Chashitsu Journey (Traveling to Tea Rooms Around Japan)

By Fujimori Terunobu and Hana

Published by Tankōsha in September 2024

ISBN: 978-4-473-04642-0

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Tankōsha.)